|

Where? Santa Maria delle Grazie Dominican Church and Convent in Milan

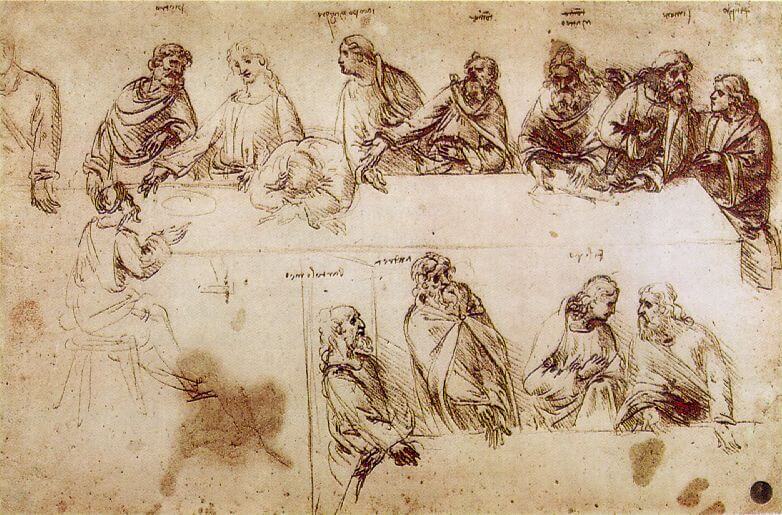

When? 1495-1498 Commissioned by? Ludovico Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan between 1494 and 1499, for the renovations he had planned for the church and convent. What do you see? The Last Supper where Jesus and the 12 apostles are sharing their final meal before the crucifixion. The fresco is designed so that the space in which the last supper takes place looks like an extension of the architecture of the room itself. In the center is Christ. His outstretched arms touch the table. The 12 apostles are divided, first into two groups of six on each side, and second, into subgroups of three. Each subgroup is a tightly-knit group in composition. Scan the row of heads and see the wave-like arrangement, surging and ebbing.

The ceiling of the room is painted as if coffered, and the coffers provide a clear sense of depth to the mural. In the background are three windows with a view to the landscape. The center window behind Christ, has a semicircular pediment, suggestive of a halo. The right wall is illuminated and the left is in shadow.

Backstory: Leonardo da Vinci always carried a sketch book with him. He looked for facial expressions, bodily movement, and believed the artist had “two principal things to paint, man and the intention of his mind.” He has frozen these 13 men in a moment of time and by doing so, he captured all the drama and excitement of the Gospel verses in The Last Supper. Few sketches remain but below is an early version.

Da Vinci had indicated great concern about painting Christ’s face. Christ is larger than the others (hierarchical perspective) and this is also of theological importance. The spatial isolation of Jesus gives added importance to his image. Da Vinci also used the most expensive paint for Christ—ultramarine.

It is hard to imagine the reactions of the friars and nuns as they entered the refectory to see the mural for the first time (before the mural started to deteriorate). The light, bright, stunning colors of a well-known story told in a brand-new fashion must have been almost shocking. Gone were the traditional halos, the flat facial expressions, the formalism, and instead, a band of 13 young men are seen reacting to an announcement that none of them could believe would happen. The humanism of Da Vinci was a great surprise. In the silence of their shared meals it must have given them much to contemplate. Restoration: Leonardo da Vinci had no experience painting frescos before he started on this mural and used an experimental technique similar to painting on a wooden panel. As a result, the painting is in very poor state as Da Vinci painted on an outside wall with no space to prevent water damage, and he painted with a mixture of oil paint and tempura. The paint did not adhere to the wall and it was decaying even during Da Vinci’s lifetime. Numerous restoration attempts have been made over the centuries, but they usually caused further problems. In 1979, a small group of Italian art restorers began a huge project to properly do the job. It took them 20 years to complete. Symbolism: Christ’s simple pose is complex in detail and meaning—he is silent, sad, and submissive. His right hand extends toward Judas, whose hand is near his. Christ’s hand is palm down, accusing Judas. “The hand that betrayeth me is with me on the table.” At the same time, Christ’s right hand refers to the glass of wine, the symbol of his blood used in the Mass, while his left hand extending to the bread refers to the symbol of his body. The triangular pose of Christ is a reference to the Holy Trinity, an emblematic abstraction of his words, “He who has seen me has seen the Father.” The hand with the forefinger pointing straight upward to the right of Christ, belongs to Thomas. His probing finger refers to the physical resurrection of Christ and points to heaven as a harbinger of the physical ascension. Refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie: The Last Supper measures 460 cm x 880 cm (15 ft x 29 ft) and covers the end wall of the refectory (dining hall) of the monastery. Painting the mural was not easy and a hazardous task as it was placed 15 feet above the floor. The theme of the Last Supper was a traditional one for refectories. The opposite wall of the refectory is covered by the Crucifixion fresco by Giovanni Donato da Montorfano, to which Leonardo da Vinci added figures of the Sforza family in tempura; these figures have deteriorated in much the same way as those in The Last Supper. Da Vinci worked very thoroughly but slowly and Montorfano was finished before him, to the consternation of Duke Sforza who exhorted Da Vinci to finish his project.

Who is Da Vinci? Leonardo da Vinci was born April 15, 1452 near Vinci in Tuscany. He was the illegitimate son of a 25 year old aspiring lawyer/notary, who had come home for the summer and met the young peasant girl Caterina. He was already engaged to be married but these occurrences were not particularly remarkable at that time.

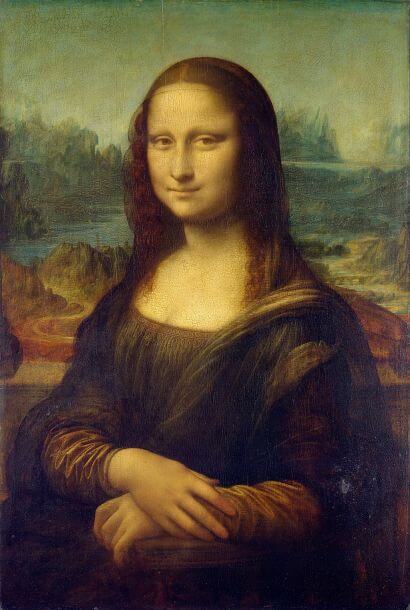

His paternal grandfather took custody of Leonardo after the birth. The fact that Leonardo was not a legitimate son may have been quite fortunate, as the first legitimate son would have had to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a lawyer. His grandfather allowed him free reign to pursue other interests. When Leonardo was 15 years old, he was sent to Florence to work as an apprentice to Andrea del Verrocchio. He excelled and by the time he was 25, he had his own studio with students. He applied to the Duke of Milan and moved there when he was 30. In 1499, following the Duke’s fall from power, he left Milan and spent a short time in Venice. He returned to Florence in 1500 and in 1516 he moved to France at the invitation of King Francis I. He died there in 1519 at age 67. Among his most famous works are the Mona Lisa in the Louvre and the Madonna Litta in the Hermitage Museum.

Fun fact: The rules of perspective that were used, bring about an unusual effect. This is especially true when looking at the table. The top of the table is always visible, no matter the angle at which you look at the painting. The nuns and friars in the refectory would be sitting well below the mural and it was important that they could see the bread and wine in this fresco.

Another interesting aspect of the fresco is the bottom center of the mural, where a doorway has been cut into the painting. In 1652, the kitchens were relocated to the room behind the refectory and they wanted easier access to the room. They cut out a good portion of the painting, included the feet of Jesus. Fortunately, in 1520, Giampietrino had made a copy of the original in oil on canvas. We can see Jesus’ feet and also the salt cellar spilled by Judas that is no longer visible in the original fresco by Da Vinci. This copy by Giampietrino was very important for the restoration of The Last Supper between 1979 and 1999.

1 Comment

Where? Room E204 of the J. Paul Getty Museum

When? 1632 What do you see? The Ancient Roman god Jupiter (Zeus in Greek mythology) is disguised as a beautiful white bull. He just seduced Europa and takes her away on his back into the sea. He has his tail up as an indication that he is happy with the successful abduction. Europa sits on top of the bull, holding a horn with her right hand, and fearfully looks back at her servants on the shore. They are the Virgins of Tyre (where Europa lived as well), with whom Europa was playing before she got abducted. They watch in disbelief how Europa gets abducted. The woman in blue has dropped the flower garland they made for the bull in her lap and raises her hands up in the air. The other woman looks at Europa while folding her hands as if she resigns in Europa’s fate. In the background is the horse carriage with four horses that had brought Europa to the beach. The story of Jupiter and Europa? This story is based on the second book of Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid (Amazon link to Metamorphoses). At the end of the second book, in lines 833 till 875, Ovid describes how Jupiter falls in love with Europa. She was the daughter of a king in an Eastern land. Jupiter asks his son Mercury to go to that land and drive the herd of royal kettle to the beach, where Europa is playing with her servants. Jupiter disguises himself as a tame white bull and puts himself among the royal kettle. Europa recognizes his beauty and starts to play with him. While a bit afraid at first, she eventually climbs on his back, and Jupiter takes that opportunity to walk into the water and escape with her on his back. This story has also inspired other painters. Titian painted The Rape of Europa in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and Jean-François de Troy painted The Abduction of Europa in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Background: This painting is one of only few paintings by Rembrandt in which he included an extensive landscape. The Getty Museum acquired it in 1995 for about $27 million, which was a new record for a Rembrandt painting at that time. They bought it together with another painting by Rembrandt, Daniel and Cyrus before the Idol Bel, which is also still in the Getty Museum.

Who is Europa? A figure in Greek mythology. She was born as the daughter of a king of a land somewhere near current-day Lebanon. She is primarily known by the story on her abduction by Jupiter who brought her to Crete. She was still a virgin before the got abducted.

Jupiter and Europa get three children together: Minos (who will become the king of Crete), Rhadamanthus, and Sarpedon. After their death, these three sons became the judges of the Underworld. The continent of Europe is named after Europa, as Jupiter took her from Asia to this new continent. Also, one of the moons of the planet Jupiter is named after her (many moons of Jupiter are named after lovers of Jupiter). Who is Rembrandt? Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born in Leiden, The Netherlands, in 1610. In 1631, he moved to Amsterdam where he initially ran a very successful painting business. He painted The Abduction of Europe in the year after his arrival in Amsterdam. He stayed there for the rest of his life and died in 1665. During his life, he experienced many challenges, like the death of his wife and children and financial trouble, but he always remained productive. Nowadays, he is considered one of the most famous artists that ever existed. Rembrandt did not paint many mythological paintings during his career. He preferred religious subjects, like Saul and David in the Mauritshuis in The Hague, or portrait paintings of individuals or groups, like he did in his famous The Night Watch in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Fun fact: Rembrandt included some great details in this painting.

Interested in a copy for yourself: Poster or canvas.

Where? Room X on the First Floor of the Kunsthistorisches Museum

When? 1565 Commissioned by? Niclaes Jongelinck, a Belgian art collector and banker. What do you see? In the left foreground, a group of peasant hunters and their dogs trudge through heavy snow as they return home from a search for food. It looks like their day was largely unsuccessful as only one hunter carries the cadaver of a small fox, and the dogs look somewhat underfed. Slowly, they pass by a group of villagers roasting corn over a fire at the inn on the far left. The sign hanging above the inn falls lopsided, skewed, maybe by the wind. In front of the hunters are the footprints of a small animal, perhaps a rabbit that has escaped them. The dogs continue sniffing at the ground in the hopes of finding it. The hunters can already see their village. Tiny figures and silhouettes are scattered across the frozen waters as they play curling, hockey, and skate around in groups. Even further behind them are more white and brown houses surrounded by dead trees and black birds, bridges, and pointed towers all dwarfed by the massive snowy mountains that loom over the entire scene. Backstory: Pieter Bruegel the Elder created Hunters in the Snow as part of his series, the Seasons. Bruegel painted scenes of autumn, winter, early spring, early summer, and summer and a sixth painting of spring has not survived. The surviving pieces of this series include: The Gloomy Day, The Harvesters, The Return of the Herd, and The Hay Harvest. Two of these paintings are in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, one is in Prague, and the last painting is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The six part series once included a painting of spring that was lost. The Seasons were commissioned for the dining room of Nicolaes Jonghelinck, a wealthy merchant and art collector from Antwerp. It’s likely that the paintings were spread out as a frieze on all four walls of the room, creating an immersive experience for the viewer. Hunters in the Snow is Bruegel’s depiction of winter. As with all his pieces, Bruegel packs each of his works with such great detail that many of the miniature scenes he creates are impossible to see with the naked eye. With these details, he crafts a realistic and immersive scene that draws viewers in and plants them into a familiar but fantastical world. Much of his work is concerned with the life of the peasant whom he respected. He gave viewers a look into the parts of their daily life.

Who is Bruegel the Elder? Pieter Bruegel the Elder was a Dutch painter who was born near Breda in 1525. Bruegel began his art career in 1555 at the Antwerp School of Art, where he created many engravings, mostly on the topic of sin, learning from the style of Hieronymous Bosch. In 1563, Bruegel left Antwerp and moved to Brussels where he would remain until his death. During this time, Bruegel began to paint more, creating his Seasons series as well as his Massacre of the Innocents in the Royal Collection in London. Much of his work was focused on day-to-day life and reality, standing in contrast to the Renaissance movement in Italy during this time.

Towards the end of his life, Bruegel painted in a “large-figure” style that sought to imitate the rhythm of dance. Works in this style include his The Blind Leading the Blind and The Land of Cockaigne. His attention to reality and detail made him one of the world’s first truly modern painters. Bruegel died in Brussels in 1569.  Detail of hunter shooting birds Detail of hunter shooting birds

Fun fact: Bruegel the Elder incorporated many details in his paintings, something that was characteristic of the Northern Renaissance style. A century before, Jan van Eyck had started this style. But Bruegel took this to another level. Some of these details can barely be seen with the naked eye. One of these includes a little hunter with a rifle shooting at some birds on the right side of the painting. With these minuscule details, Bruegel is able to create a world full of depth and truth.

Where? Many museums own a woodblock print of this work, including the Art Institute of Chicago, British Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, but this work is usually not on permanent display.

When? 1829-1832 What do you see? A giant wave off the shore of the Kanagawa prefecture dwarves three boats — one in the foreground, one in the middle ground, and one in the background. The perfect curves of the wave’s form the relentless rocking feeling that terrifies the occupants and rowers on the tiny boats. Perhaps they are fishermen. Above them, it’s raining seafoam, represented with delicate white specks and claw-like crests. In the distance, standing before a grey haze is Japan’s great Mount Fuji. The mountain balances the downward curve of the wave while emphasizing the enormousness of the wave. Backstory: Hokusai created The Great Wave as part of a series of landscapes titled Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjurokkei). Mount Fuji, a sacred spiritual site in Japanese culture, appears in every print in the series, but is not conspicuous in every piece. Often, it appears in the background of the prints such as in the case of The Great Wave off Kanagawa. The scenes that Hokusai created surrounding Mount Fuji were drastically different, varying in season, setting, and overall atmosphere. There are serene scenes such as Inume Pass in the Kai Province, lonesome scenes such as Tama River in Musashi Province, and intense scenes like The Great Wave. Showing the important landmark from several locations, Hokusai emphasized the permanence and stillness of Mount Fuji. No matter the condition of life, the mountain would remain exactly where it stands.

Ukiyo-e: Ukiyo-e, meaning “pictures of the floating world,” was the major art style of the Edo period, which was popular between 1603 and 1868 in Japan. During this time, under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, ideas like sensuality and tranquility were promoted, prompting the creation of a genre of art depicting leisurely daily life.

Ukiyo-e began on silk screens depicting life in the urban sphere. The genre blew up when ukiyo-e artists began creating woodblock prints. The medium allowed for mass production and mass consumption. These images of courtesans, kabuki, daily activity, and nature soon spread to Europe once Japan opened its ports in 1853 spurring the Impressionist movement and inspiring artists such as Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Who is Hokusai? Katsushika Hokusai was a prominent printmaker and painter of the Edo period. He was born in 1760 and died in 1849 after a long career of art making. When he was 19 years old, he studied under Katsukawa Shunsho who gave him the skills to begin producing his own unique artworks when he was 20. After a dispute with his teacher, Hokusai ended his studies and began making sketches for woodblock prints that would be turned into picture calendars alongside his own prints of portraits of women. Soon he became a major player in the ukiyo-e movement, competing with Hiroshige and creating illustrations and paintings for popular fiction books. A practicing Buddhist, Hokusai paid special attention to nature, and, in his own time, he produced many landscape paintings and prints including Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji in which his unique style became more prominent. He also painted birds and flowers with bright, intense colors. Hokusai was careful to depict daily life without any exaggerations but with great beauty. Towards the end of his life, Hokusai grew weak in both his health and skill. Nonetheless, before his death at the age of 89, Hokusai created numerous works depicting mystical images such as demons and dragons, a change of pace from his typically realist style. Fun fact: French composer Claude Debussy is said to have been influenced by Hokusai. When Japan opened its ports in 1853, the japonisme movement took over Europe. People quickly got their hands on Japanese goods like furniture and artwork that they would use to decorate their homes. As a student in Rome, Debussy frequently purchased Japanese goods. One of the prints that he discovered and hung on the walls of his home in Paris was The Great Wave which is said to have inspired his masterpiece, La Mer.

Where? Room 2 of the Musée d’Orsay

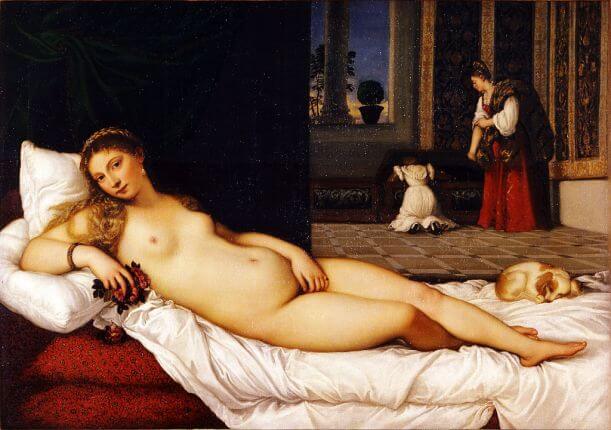

When? 1863 What do you see? A beautiful Venus is born from the foam of the sea. It looks as if she has just awakened from a deep slumber. She languidly rests her head upon a small wave that is beginning to form on the far right. The waters seem to conform to her twisted contrapposto, perfectly following the shape of her waist. Upon first glance, her eyes are shut. But a closer look reveals that they are half-open, pointed upwards as she looks into the crook of her right elbow. Her golden hair flows from beneath her left arm, floating beside her in the blue-green waters. Above her is a pastel sky decorated with thin clouds and five cherubs that are celebrating and announcing her arrival with horns made of seashells. The three cherubs closest to her face peer over her body with playful curiosity, arms stretched out, perhaps preparing to wake her. Backstory: Alexandre Cabanel exhibited The Birth of Venus in the Paris Salon in 1863 in a “Salon of Venuses”. During this time, many artists were painting female nudes shrouded in the mythology of the birth of Venus. The European idealized female nude, a tradition that traces back to the Venus of Urbino by Titian, was experiencing a revival in the 19th century in works like Cabanel’s, as well as the Grande Odalisque by Ingres, and the Maja Desnuda by Goya. The mysticism of the story gave artists room to produce semi-erotic works without offending the public. Cabanel’s Venus is posed in a much more provocative way than Olympia by Manet, but because of Manet’s more realistic and confrontational take on his nude, he received a great deal of criticism in the same year.

What is contrapposto? Contrapposto is a pose that was developed by the Greeks. In contrapposto, the figure rests its weight on one leg and bends the other. The axis of the shoulders and the hips are positioned in opposite directions to create a sense of dynamism and depth. This creates a natural resting pose that makes the figure come alive.

Who is Alexandre Cabanel? Alexandre Cabanel was a French painter born in 1823 in Montpellier, in the south of France. When he was seventeen years old, he enrolled in the Ecolé des Beaux-Artes in Paris. Following his first exhibition in 1844, Cabanel was awarded the Prix de Rome. His work was quickly popularized at the Paris Salon. Cabanel primarily painted in the Academic style and drew inspiration from the Rococo art movement. His works centered around classical, religious, and historical themes. The Birth of Venus, his most famous painting, was exhibited at the Paris Salon and later purchased by Napoleon III. In his later life, Cabanel served as a juror for the Salon and returned to the Ecolé des Beaux-Artes as a teacher. He died in Paris in 1889 at the age of 65. Fun fact: Following the creation of the original, Alexandre Cabanel sold reproduction rights to Adolphe Goupil, an art dealer and publisher. Working with copyist Adolphe Jourdan, Cabanel was able to produce numerous replicas of his take on The Birth of Venus. One of these replicas is on display in the Dahesh Museum in New York. Another one belongs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art but is not on permanent display.

Where? Room 96 of the Uffizi Museum

When? 1597 Commissioned by? Cardinal del Monte, who gave it as a gift to Ferdinando I de Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany What do you see? A depiction of the head of Medusa painted on a circular and curved wooden shield. Medusa is a figure described in Greek mythology. With her glance she could turn people who looked at her into stone. Instead of normal hair she has living, venomous snakes on her head. The snakes are watersnakes from the Tiber river as those were the best type of snakes Caravaggio could find nearby. I count at least eight snakes on her head. The blood streams out of her head as she has just been killed by the Greek demigod Perseus. This painting shows the moment that Medusa is looking at the reflective shield that Perseus is holding (which according to the myth actually happened just before she got beheaded). She realizes that her head is separated from her body, but that she is still conscious. You can see this realization by the horror in her eyes. As the painting is created on a shield, Caravaggio’s idea was that this painting actually represents the view of the shield as held by Perseus just after he killed Medusa. It is also interesting to have a closer look at Caravaggio’s use of light and shadow in this painting. Do you see how Caravaggio used these contrasts to show the head of Medusa as a three-dimensional object?

Who is Caravaggio? Michelangelo Merisa da Caravaggio (1571-1610) was trained by Simone Peterzano, who was in turn trained by Titian. He used a realistic painting style, paying attention to both the physical and emotional state of the subjects he painted. He combined this with a beautiful contrast between light and shadow in his paintings. He was a brilliant and unconventional artist.

During his life he received quite some commissions for religious paintings. However, Caravaggio always knew to how add some dark elements to the painting. He liked to use beggars, criminals, and prostitutes as models for his paintings, which would often give unexpected outcomes for familiar biblical scenes. Two beautiful examples of his religious paintings are the Death of the Virgin in the Louvre and The Entombment of Christ in the Vatican Museums.

Who is Medusa? In Greek mythology, Medusa was one of three sisters (Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa) who were often referred to as Gorgons. Both Stheno and Euryale were immortal, but Medusa was not. They were daughters of Phorcys (a sea god) and his sister Ceto (a sea goddess).

According to the Roman poet Ovid, Medusa was a beautiful young woman. However, after Poseidon (the god of the sea) made love to her in Athena’s temple, Athena (the goddess of wisdom and war) changed her beautiful locks into living, venomous snakes (in other mythological stories the three sisters were already born with snakes on their heads). Medusa had a horrific facial expression that could turn people (or according to some, only men) who looked at her into stone. The Greek hero Perseus, a demigod, used a shining shield that he got from the goddess Athena to avoid looking at her directly and succeeded to cut off her head. He used her head as a weapon afterwards as it retained its power to turn people who looked at it into stone. Perseus ultimately gave the head of Medusa to the goddess Athena, who placed the head on her shield (which is what is depicted in this painting). When the head of Medusa was cut off, two creatures arose from Medusa’s body: Pegasus, a winged horse, and Chryasor, a giant with a golden sword. Medusa in art? Medusa has been a popular subject in art. Famous artists have used her story as the inspiration for their artwork. Well known versions include:

Fun fact: Monica Favaro and colleagues published an academic study about the materials that were used in this painting and the evolution of these materials over time.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas (Amazon links).

Backstory: This painting is called the Madonna Litta because of a previous owner of the painting, the art collector, count Antonio Litta, from Milan, Italy. Tsar Alexander II acquired this painting in 1865 for the Hermitage Museum.

It is not known when Leonardo da Vinci made this painting exactly as he liked to do multiple projects at once and he often took a long time to complete a painting. What is known is that, in 1479, he already completed the first sketch of a nursing Madonna (now in the Royal Library at Windsor, England). After that, he completed more preparatory works for this painting, including a sketch of the face of Mary which is now in the Louvre. It is assumed that Leonardo started this painting in 1481 and that he stopped working on it for a while because of other commissions.

Symbolism: The scene of the Virgin Mary breastfeeding Baby Jesus shows motherhood and motherly love. The blue mantle of Mary symbolizes the Church and her red dress is a symbol of the passion of Christ. The goldfinch is a symbol of the future crucifixion of Jesus. The mountain landscape in the background represents the greatness of the Creation of the world by God.

What is Madonna Lactans? The Virgin Mary breastfeeding Baby Jesus is the perfect example of motherly love. This theme is referred to as Madonna Lactans or Nursing Madonna. Madonna Lactans has been the subject of quite some paintings from the 12th century until the middle of the 16th century when the Council of Trent discouraged the use of nudity in religious paintings. Madonna Lactans was also a frequent theme in the Orthodox Art in Russia, and this theme is better known as Mlekopitatelnitsa. This may explain why the Russian Tsar Alexander II bought this painting for the Hermitage Museum. Who is Leonardo da Vinci? Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (1452-1519) was an expert in a large number of different fields, including astronomy, geology, mathematics, music, and painting. He was born in Vinci, near Florence, and received his artistic education in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio. During that time, he already created Ginevra de’ Benci, which is in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. After he finished his apprenticeship with Verrocchio in 1478, he moved to Florence, and in 1482 he moved to Milan where he stayed until 1499. There he worked on many different projects, and he often moved on to the next project leaving the previous one unfinished. Over the next decade, he lived in several different places in Italy. During this time, he created his famous Mona Lisa.

Fun fact: There is a lot of debate whether this painting should be attributed to Leonardo da Vinci or one of his assistants. In 1482, Leonardo mentioned that he had completed one Madonna (probably the Benois Madonna, which is also in the Hermitage Museum) and had almost finished another one. This other Madonna can either be the Madonna Litta or the Madonna of the Carnation, which is in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

The main reason that people doubt whether this painting is entirely created by Leonardo is the plain landscape, the somewhat dull outfit of Mary, the shadows in this painting, and the lack of details in her face (compare this to Leonardo’s drawing in the Louvre above). People argue that these aspects are not of the quality that we could expect from Leonardo. However, experts agree that the design of the painting and especially the complicated pose of Mary and Baby Jesus could well be from Leonardo. So, it is not unlikely that Leonardo has started this painting, but that an assistant, maybe Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, finished the painting. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster.

Where? Gallery 5 of the Legion of Honor Museum

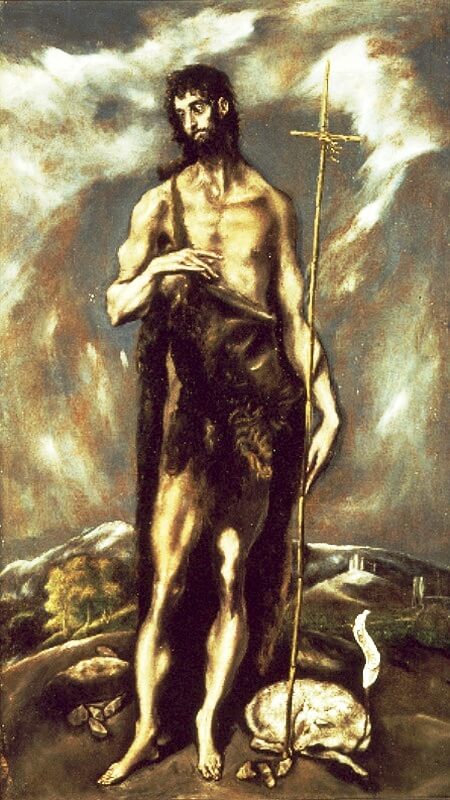

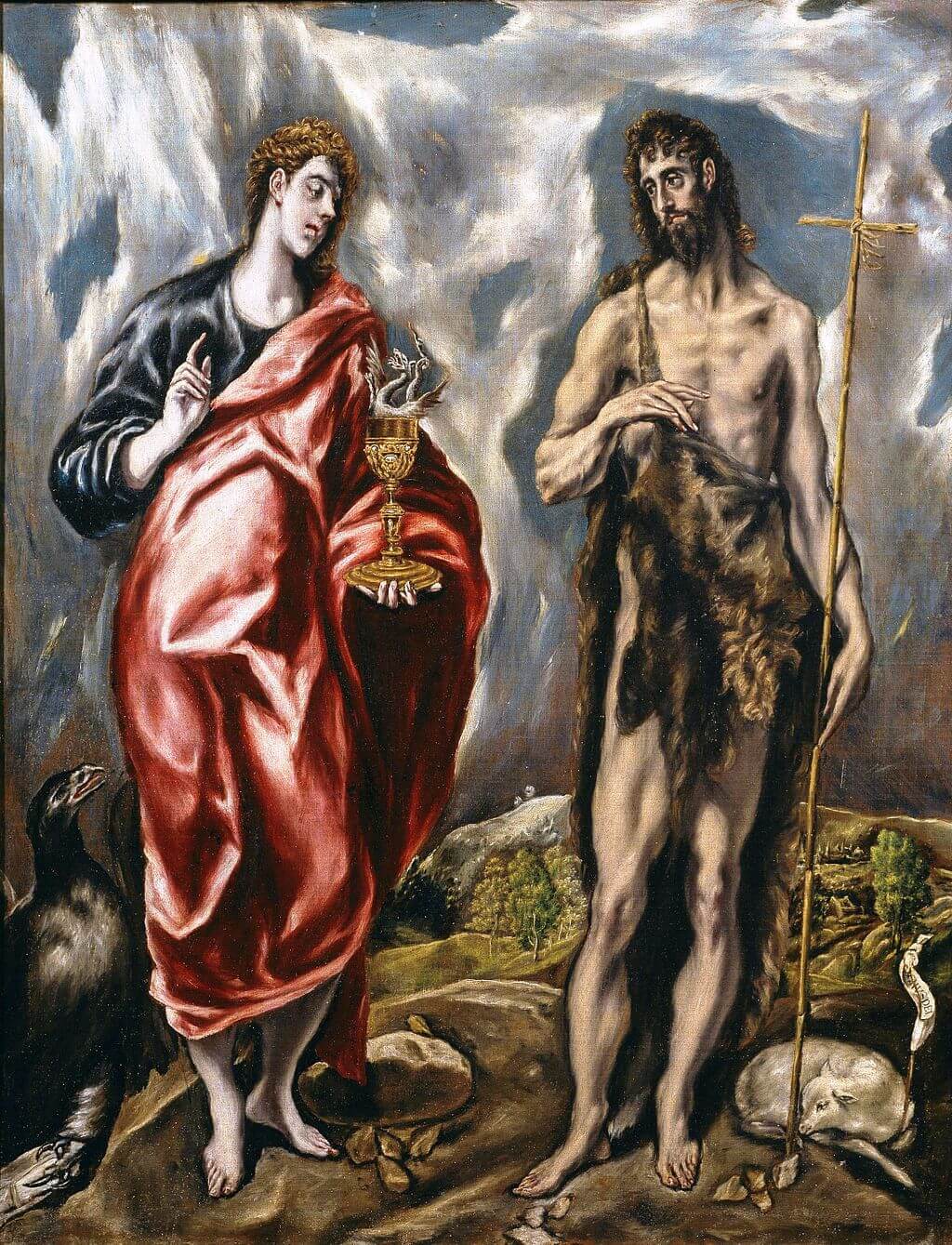

When? Around 1600 Commissioned by? The Convent of the Discalced Carmelites in Malagón, Spain. What do you see? The elongated figure of Saint John the Baptist. He looks unusually tall and thin, typical of the style of El Greco. Saint John the Baptist wears a robe of camel skin, and a long cross stands to his side. On the right, a lamb lies down on a rock. Next to the rock is a stick with a banner reading “AGNUS DEI” (Lamb of God), which is how Saint John the Baptist refers to Jesus in John 1. The Lamb of God refers to Jesus’ role in taking away the sins of the world through his crucifixion (to which the cross explicitly refers). El Greco uses a low horizon and dedicates more than half of the painting to a luminous sky. The bright light from the sky reflects on the hills in the background. El Greco places Saint John the Baptist in the middle of a landscape. The building next to his left knee is the Monasterio del Escorial, a historical residence of the King of Spain located 30 miles outside of Madrid. Backstory: El Greco painted this work while living in Toledo, Spain. The Legion of Honor Museum acquired this painting in 1946. It is displayed next to two other paintings by El Greco in the museum. Other versions: El Greco painted several variations on this painting. A very similar version of Saint John the Baptist is in the Museu de Belles Arts de València. The main difference between both versions is that El Greco worked out some more details in the background of the Legion of Honor version, and he changed the placement of the lamb next to Saint John the Baptist. Another similar version of Saint John the Baptist is owned by the Prado Museum and on display in Toledo. This version shows Saint John the Baptist together with Saint John the Evangelist. For this painting, El Greco used the help of his workshop.

Who is Saint John the Baptist? A preacher who foretold the coming of Jesus. During his life, he baptized many people to wash away their sins. His most important deed was the baptism of Jesus. He is the patron saint of Jordan and Puerto Rico, as well as cities like Florence and Porto.

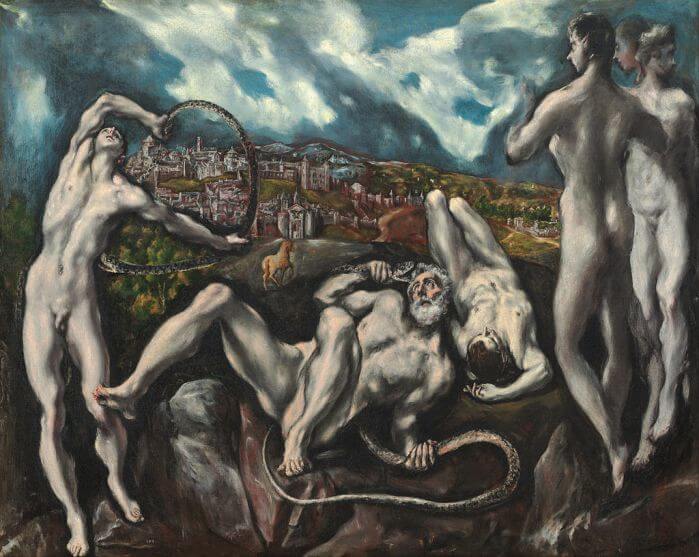

Who is El Greco? Doménikos Theotokópoulos was born in 1541 in Heraklion, Greece, and died in 1614 in Toledo, Spain. He is better known as El Greco (the Greek). During his twenties and thirties, he spent several years in Italian cities like Venice and Rome, where he got inspiration from artists like Michelangelo, Tintoretto, and Titian. He eventually moved to Toledo, near Madrid. El Greco developed a unique style that is difficult to classify as it was so different from all other painters. He was a Mannerist, he was very expressive, and his works contain some fantasy-like elements. His work has inspired many artists over time, including Delacroix, Manet, and Picasso. He painted both religious and mythological works. An example of the latter is his Laocoön in the National Gallery of Art.

Fun fact: The extremely elongated figures are a recurring theme in the works of El Greco. It is not certain why El Greco used this style, but there are two main explanations.

Where? Room I of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich

When? 1529 Medium and size: Oil on panel, 158.4 cm × 120.3 cm. Commission: Duke William IV of Bavaria commissioned a series of historical paintings from various artists for his summer house at the Royal Study. They included both biblical and other historical paintings. What do you see? It shows the cosmic battle at Issus in 333 BC. Altdorfer captured the end of the battle between the Persian King Darius III and Alexander the Great. The painting contains thousands of warriors on the battlefield. In the left foreground, the army with the red and black lances is the Persian one of Darius III. They go head to head with the Hellenic squadron, in the right foreground, fighting for Alexander the Great. Just above this battle is the main scene with, on the left, Darius III on his chariot carried by three off-white horses. He is fleeing the battlefield, realizing that they have lost the battle. To his right, leading the Macedonian army with his outstretched lance is Alexander the Great chasing Darius III. Above the scene with Darius and Alexander, more battles occur with the Macedonians on the right and the Persians on the left. The banners for each army contain information on the supposed number of soldiers killed and taken hostage.

Where? Room W204 of the J. Paul Getty Museum

When? 1878 What do you see? A street full of French flags on the day that the French people celebrated the fête de la Republique. This work is painted during the afternoon of June 30, 1878. Several well-dressed people walk through the street, and we can see some horse-drawn carriages as well. On the lower left is a man with one leg. He hunches and wears a blue cape. He is dressed as a laborer and is probably a war veteran. Behind the laborer is a ladder, and to his left is half of a railroad track. To the left of this track is a wooden fence, behind which are the leftovers of a building that had collapsed. On that spot, a new train station was built, the Gare Saint-Lazare. Backstory: This national holiday was celebrated enthusiastically throughout Paris. However, Manet did not depict the most representative scene from that day. The Rue Mosnier was not a very big street and certainly not the street where the wildest celebrations for the national holiday took place. Nowadays, the street is called the Rue de Berne. Manet painted this work in front of a second-floor window in his studio overlooking the Rue Mosnier. The Getty Museum acquired this painting in 1989 for $26.4 million, which was the highest price paid for a Manet painting at that time. Other versions: Manet painted this street two more times. Both versions are in a private collection. One version, Rue Mosnier with Pavers, shows the street on a normal day when the street is paved. Manet painted the other version, Rue Mosnier Decorated with Flags, earlier on the day on June 30, 1878. This version is a more festive, but less refined depiction of the celebrations.

Moral message: Manet shows the contrast between the celebration of the National Day of France and the consequences of the Franco-Prussian war in 1870-1871 (a war between France and Germany). The well-dressed people, horse carriages, and flags show the prosperous side of France which can be celebrated. In addition, this celebration is in honor of the successful World Expo that took place in Paris.

In contrast, the one-legged man on the bottom left is probably a war veteran who lost his leg in the war earlier that decade. The leftovers of the railroad track and the collapsed building on the left, represent the war consequences. Manet illustrates that while some people can be happy with their country, others still suffer the consequences of the turbulent past and there is still much work necessary to build up the country.

As a young painter, Manet was influenced by the works of Frans Hals and Diego Velázquez. However, he developed his own painting style and became one of the founders of Impressionism. This painting is a good example of his Impressionist work. His innovative works have had a big impact on the development of future painting styles.

Fun fact: Manet originally created a picture of the disabled man in the bottom left for a music album to be published in 1878. Manet made a drawing of a disabled man, owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for a music album, Les Mendiants. The album, created by the unconventional musician Cabaner, is based on poems from a book, La Chansons de Gueux, by Jean Richepin. Beggars, prostitutes, and other outcasts formed the theme of the album.

One of the poems specifically dealt with a disabled man who was begging outside a church. In the end, the album was never released, and Manet could thus use the image of the disabled man for this painting. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us