|

Where? Gallery 201 at The Art Institute of Chicago

When? 1877 What do you see? A busy, rainy street near the Saint-Lazare station in Paris. The canvas is divided in half by an axis, a tall green streetlamp. Walking on the right of it, in the foreground, are a couple dressed in the latest Parisian fashion. As they walk arm in arm beneath an umbrella, looking off to the left side of the canvas, a stranger passes them with his back to the viewer. Judging by the young woman’s brown dress and diamond earring, the pair are likely of the upper class. The men in the middle ground appear to be dressed in a similar fashion. Further down the canvas are some traces of the working class. Behind the man’s umbrella, a painter dressed in white carries a ladder across the street. Behind the woman, a baker looks out her window. Two carriage drivers can be seen on the left side of the street lamp.

Backstory: Exhibited at the Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877, Paris Street; Rainy Day was celebrated by many. The natural scene of a real Parisian street painted in a realistic fashion calls back to Caillebotte’s interest in photography. However, the painting’s style cannot be characterized as entirely realist or academic.

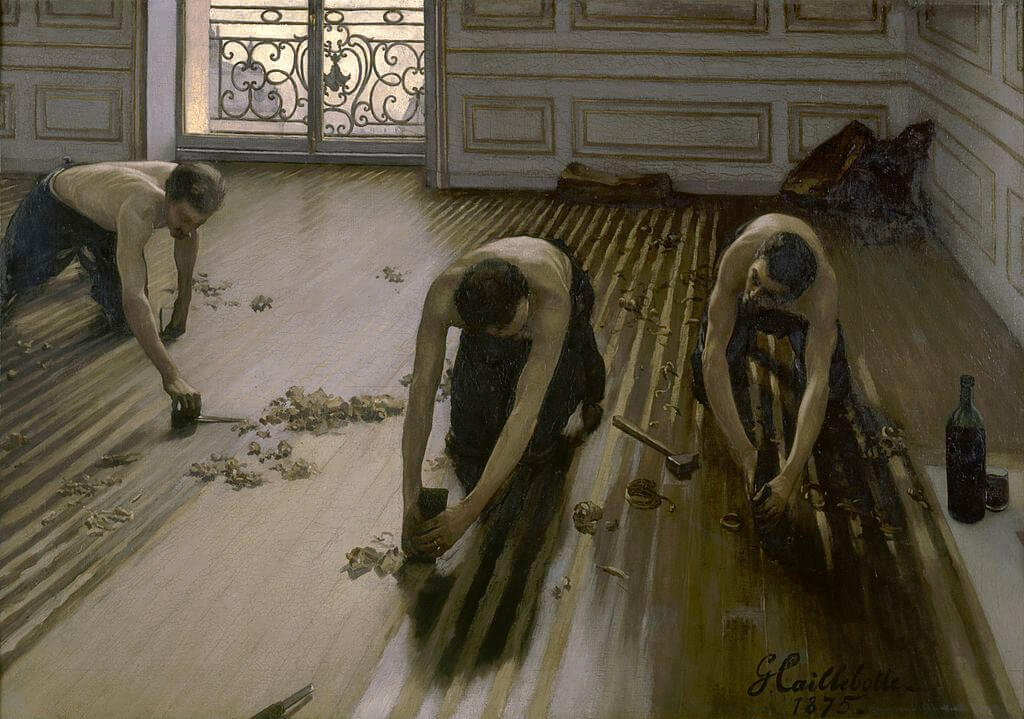

Caillebotte features an unusual asymmetrical composition and cropped figures. On the right side of the canvas, the man and woman’s legs are out of frame and the stranger with his back to the viewer is split in half. This detail may be overlooked by modern viewers but was considered radical by Caillebotte’s contemporaries. The cropped composition may have been inspired by his interest in photography. Featuring unsaturated colors and dim light, the painting has a gloomy and slow feeling. Subtly showing the division between the bourgeoisie and the working class, Caillebotte’s palette suits the daunting disparity that is most heavily felt by the workers. Who is Caillebotte? Gustave Caillebotte was born in 1848 in Paris and died in Gennevillers in 1894. He grew up in a wealthy family and began painting in the studio of Leon Bonnat. In 1873, Caillebotte began his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts and shortly after became acquainted with Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet. With his money, he was able to support many artists like Edgar Degas, Camille Pissaro, and Alfred Sisley. Although he did not participate in the first one, Caillebotte exhibited eight paintings in the Second Impressionist Exhibition of 1876, one of which was The Floor Scrapers in the Musée d’Orsay. Caillebotte’s academic style combined with an Impressionist influence produced a unique and modern style of art.

Never truly sticking to one style of painting, Caillebotte aimed to depict modern life for what it really was in the realist sense. Nonetheless, an Impressionist influence is evident in his loose brushstrokes and “cropped” paintings.

Fun fact: On the ground floor of the center building in the background, there is a green “pharmacie” sign with yellow letters. Nowadays, the same building, located in between Rue de Moscou and Rue Clapeyron, still has a pharmacy.

0 Comments

Where? Gallery 243 of The Art Institute of Chicago

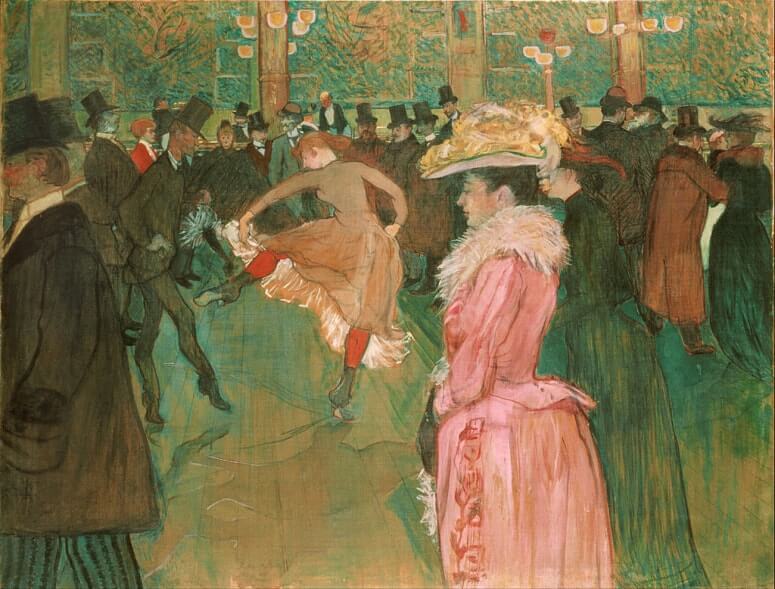

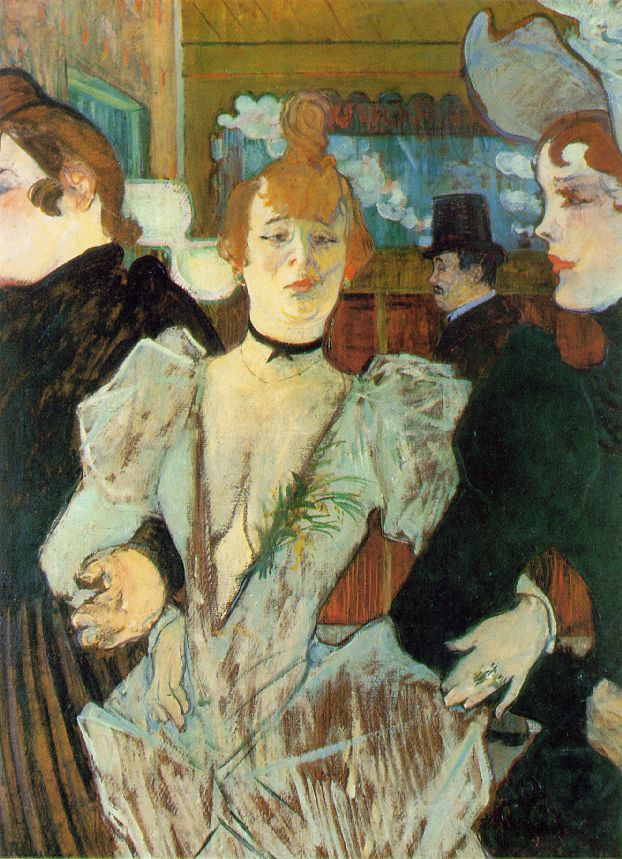

When? 1892-1895 What do you see? Behind a balustrade in one of the most popular nightclubs in Paris, three men and two women sit at a table, leaning into conversation. There are drinks on the table and each member of the party wears a fancy hat. The woman with orange hair is Jane Avril, a famous entertainer. Behind their table, one tall and one short man are passing by. In the right background, two women stand by a green mirror. The one fixing her hair is dancer La Goulue. Looking deeper into the room, there are many more guests sitting at tables with yellow lights hanging above them. Such a light may hang above the dancer May Milton in the left foreground. She stares at us with her bright teal skin, and her features have become grotesque and distorted under the harsh nightclub lights. Backstory: In the risky neighborhood of Montmartre, Paris, nightlife flourished through the end of the 19th century. People of various classes came to the nightclubs and dance halls in Montmartre to experience a social life unlike any other. In its heyday, the area was actually quite dangerous, but it has since been romanticized and sensationalized so that images and music associated with it evoke great nostalgia. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec frequently visited the Moulin Rouge, a nightclub in the neighborhood. As such, he was very familiar with the other regulars. In At the Moulin Rouge, he was able to capture these characters on canvas and portray the true grunge of the Paris nightlife culture. Using bright colors and thick brush strokes, Toulouse-Lautrec paints in an Avant-Garde style, apt for his subject matter. What is the Moulin Rouge? Established in 1889, the Moulin Rouge was a cabaret and nightclub located in the Montmartre district of Paris. Featuring live performances from the stars of Paris, drinks, and room for socialization, the Moulin Rouge was a truly modern space. The iconic can-can dance was first performed at the Moulin Rouge, and, at the time, it was considered a very improper dance. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec created several advertising posters for the Moulin Rouge, as well as several paintings of the Moulin Rouge. Among those paintings are At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and La Goulue at the Moulin Rouge in the Museum of Modern Art.

Who is Toulouse-Lautrec? Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec was born in Albi, France in 1864 to a wealthy family. As his mother and father were first cousins, Toulouse-Lautrec suffered from congenital health issues that affected his bones and growth. Due to these health issues, he became slightly isolated from society and spent his time making art. Painting in the Post-Impressionist style and printmaking in the Art Nouveau style, Toulouse-Lautrec captured the Bohemian lifestyle of 19th-century Paris. This was the lifestyle Toulouse-Lautrec immersed himself in Montmartre’s Moulin Rouge. He created a series of posters advertising the cabaret and displayed his artworks there.

Fun fact: The two men walking behind the table in the center of the painting are actually Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec himself and his cousin, Dr. Gabriel Tapié de Céleyran.

Where? Many museums own a woodblock print of this work, including the Art Institute of Chicago, British Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, but this work is usually not on permanent display.

When? 1829-1832 What do you see? A giant wave off the shore of the Kanagawa prefecture dwarves three boats — one in the foreground, one in the middle ground, and one in the background. The perfect curves of the wave’s form the relentless rocking feeling that terrifies the occupants and rowers on the tiny boats. Perhaps they are fishermen. Above them, it’s raining seafoam, represented with delicate white specks and claw-like crests. In the distance, standing before a grey haze is Japan’s great Mount Fuji. The mountain balances the downward curve of the wave while emphasizing the enormousness of the wave. Backstory: Hokusai created The Great Wave as part of a series of landscapes titled Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjurokkei). Mount Fuji, a sacred spiritual site in Japanese culture, appears in every print in the series, but is not conspicuous in every piece. Often, it appears in the background of the prints such as in the case of The Great Wave off Kanagawa. The scenes that Hokusai created surrounding Mount Fuji were drastically different, varying in season, setting, and overall atmosphere. There are serene scenes such as Inume Pass in the Kai Province, lonesome scenes such as Tama River in Musashi Province, and intense scenes like The Great Wave. Showing the important landmark from several locations, Hokusai emphasized the permanence and stillness of Mount Fuji. No matter the condition of life, the mountain would remain exactly where it stands.

Ukiyo-e: Ukiyo-e, meaning “pictures of the floating world,” was the major art style of the Edo period, which was popular between 1603 and 1868 in Japan. During this time, under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, ideas like sensuality and tranquility were promoted, prompting the creation of a genre of art depicting leisurely daily life.

Ukiyo-e began on silk screens depicting life in the urban sphere. The genre blew up when ukiyo-e artists began creating woodblock prints. The medium allowed for mass production and mass consumption. These images of courtesans, kabuki, daily activity, and nature soon spread to Europe once Japan opened its ports in 1853 spurring the Impressionist movement and inspiring artists such as Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Who is Hokusai? Katsushika Hokusai was a prominent printmaker and painter of the Edo period. He was born in 1760 and died in 1849 after a long career of art making. When he was 19 years old, he studied under Katsukawa Shunsho who gave him the skills to begin producing his own unique artworks when he was 20. After a dispute with his teacher, Hokusai ended his studies and began making sketches for woodblock prints that would be turned into picture calendars alongside his own prints of portraits of women. Soon he became a major player in the ukiyo-e movement, competing with Hiroshige and creating illustrations and paintings for popular fiction books. A practicing Buddhist, Hokusai paid special attention to nature, and, in his own time, he produced many landscape paintings and prints including Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji in which his unique style became more prominent. He also painted birds and flowers with bright, intense colors. Hokusai was careful to depict daily life without any exaggerations but with great beauty. Towards the end of his life, Hokusai grew weak in both his health and skill. Nonetheless, before his death at the age of 89, Hokusai created numerous works depicting mystical images such as demons and dragons, a change of pace from his typically realist style. Fun fact: French composer Claude Debussy is said to have been influenced by Hokusai. When Japan opened its ports in 1853, the japonisme movement took over Europe. People quickly got their hands on Japanese goods like furniture and artwork that they would use to decorate their homes. As a student in Rome, Debussy frequently purchased Japanese goods. One of the prints that he discovered and hung on the walls of his home in Paris was The Great Wave which is said to have inspired his masterpiece, La Mer.

Where: Gallery 248 at the Art Institute of Chicago

When: c. 1893 Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 65 cm x 80 cm (25.6 x 31.5 in.). What do you see? At first glance, the tabletop, the basket of apples, wine bottle, plate of biscuits, apples tumbling across the tablecloth and surfaces, may appear to be a straightforward still-life painting but a longer look will show that it is much more than that. Cézanne had been rejected by the public for so many years that he had freed himself to see and paint to his own dictates. His still-life depictions are complex compositions that continue to provide the harmony and unity of his subjects that was so important to his philosophy of art, but he was experimenting at the same time. At first glance, we see a pleasing colorful painting that invites us in for a longer look. Cézanne, while showing himself and his viewers a kaleidoscope of perspectives, broke the rules of art with impunity. This painting provides a perfect example of what he did in order to portray our human visual perceptions that operate on so many levels in order to interpret our surrounding environment and what we see. Impossible Perspective? The longer look reveals a table that is impossible. The supports on the left and right sides are not the same height. The tabletop is not even on both sides and also not the same color. An extra tabletop can be seen on the right side. The back of the table on the left and right sides are also not on the same levels. We are looking at a variety of differing viewpoints. The table is tilted towards the viewer and on the left, yet another level supports the apple basket in a position that seems impossible as well. Does the wall support the basket? The green wine bottle is not symmetrical and leans slightly towards the left. Does it also support the basket? Even the biscuits on the plate provide differing views; we see both a side and top view at the same time. Cézanne has manipulated the biscuits by angling and elevating the two upper biscuits so we see two whole tops. There is a grey gap on the right side that creates a tilt in the edge of the upper back part of the table. It gives the impression that the right back part of the table is holding some of the fruit in place to keep it from rolling off into space. A pear at the edge of the gap also seems to act as a stopper. The folds of the tablecloth contain some of the loose fruits with a power that is stronger than simple cotton. Cézanne was known to impregnate his cloths with plaster of Paris to make them firm. Perhaps this is an example of that technique. A long grey fold that starts just right of the center of the painting, guides the eye into the scene and it provides a suggestion of depth, yet the cloth still seems to be about to fall from the table because of the illusion of a forward tilt. The feeling is augmented by the lack of a clear table edge on the left side. The wine bottle provides a vertical center that is surrounded by a variety of horizontal planes that do not interfere with the perception of the whole. Cézanne made clever use of grey tones on the wall, on the basket support, the plate of biscuits, the grey gap in the table on the right and the grey on the table in the front, plus the grey highlights on the cloth to unite all elements. Back Story: Paul Cézanne was 54 years old in 1893 and would only live another 13 years. His exploration of techniques, styles and mediums was extensive by this time and covered his full range of compositions and subjects. His progress over time is clearly visible whether he was painting a portrait, a landscape or a still life. His concerns centered on the artist’s interpretation and portrayal of a subject. His viewers should perceive all sides and the inside-out in their perception of harmony and unity in his works. He wanted his viewers to see and feel the wind in a landscape, find the personality in a portrait, and understand all sides of the objects in a still-life as he presented it. How we perceive visual stimuli was a major concern in all he did. Influence of Chardin: In his early years, Cézanne visited the Louvre and became familiar with the work of Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin. Chardin had been considered one of the most revolutionary artists of 18th century France, in particular having raised the lowly art form of still life painting to a level of popularity not known before in France. His desire to paint reality came from the Age of the Enlightenment. “Sensations of the mind” were being questioned. There was the belief that painters could “manipulate colors and shapes to induce particular responses in the viewer”. The American art historian Theodore Reff suggested the influence that Chardin may have had on Cézanne: “It would be hard to imagine the emergence of still life as a major category of modern art without the example of Cézanne from about 1875 on and equally hard to imagine his achievement without the revival of Chardin some thirty years earlier … Chardin did not use trompe-l’oeil to deceive by an optical illusion … his aim was to re-create the living, moving character of the vision of reality.”

Chardin tended to place his objects in a line, interacting with each other but separate. A slice of brioche and a bite of the cherries from the table is inviting. He always led viewers into his still-life by using a long object as above or a knife in order to emphasize the depth of the table. Cézanne used the same technique as both artists attempted to imitate reality on canvas. But Cézanne took the genre into another level of perception as described above and seen below.

The differences in the compositions of these two artists may be subtle but Chardin’s horizontal plane is absolute. The knife and the rumpled cloth lead the eye into each painting but Cézanne plays with our perceptions of reality as he tilts the plate of cherries to give us the best possible view. He was not afraid of deviating from the linear perspective that artists and collectors were so familiar with. Chardin’s stacked peaches provide the vertical element just as the green jar does in Cézanne’s work. Chardin’s perfect peaches even provide the fuzz, where Cézanne’s peaches have imperfections. His paint spills out of the outline, layers of green beneath are visible but when looked at from a distance, they remain realistic and appealing.

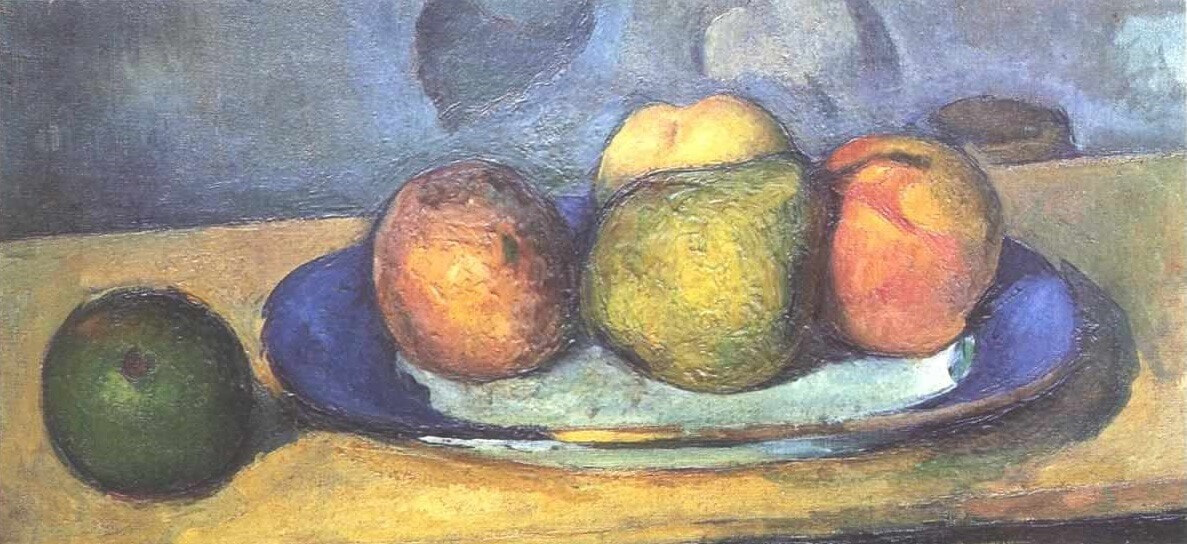

Still-Life Paintings by Cézanne: Cézanne said he wanted to “shock Paris with an apple.” Never before had everyday objects been presented in quite the manner in which he painted. He was always concerned with “color value, color schemes and creating form with color. His hatching style of brushstrokes and his outlining gave his objects their own subjective space” (Duchting, 2003). His Fruits on a Blue Plate seen above, reveals each technique. Tonally blue, simple color scheme of blues and yellow (blue and yellow make green), the distinctive brush strokes on the fruit, layered to give volume and form, and the final outlining to separate each object, yet he maintains their intimate relationships. There is a blue haze over the whole painting uniting the parts.

Still Life with a Ginger Jar and Eggplants, painted between 1893 and 1894, shows how the blue drapery with its patterns and folds gives volume and texture to the painting. There is a slight suggestion of a table on the left-hand side near the bottom but without that, the materials and objects look almost suspended in air. Cézanne integrates his geometric shapes of circles, triangles and domes to compose interesting pattern after pattern. The relationship between the ginger jar and the green objects catches the eye. The brownish pear behind the plate of fruit transitions the colors of the rum bottle and the eggplants so they are included in the grouping in a natural manner. The pear with its yellowish highlights, helps to keep the relationship with the plate of fruit and the lemon on its own, as integral to the work. Cézanne has tilted the plate to provide a good view of all the fruit but again disregards the rules of linear perspective as these fruits should be falling onto the floor. He keeps us off balance by painting an impossible table in the background. Legs may be intimated but we cannot see them, and the table should be falling too.

Cézanne worked slowly and each brush stroke was thought out a thousand times. To Gasquet (his young student and confidante), he said: “You have to get hold of these fellows … these glasses, these plates, they talk to each other, they’re constantly telling confidences.” The intensity and the love that he put into these objects is remarkable. Cézanne’s motifs may be still or appear quiet but he creates tension and suspense that draws an emotional response from his viewers. Again, to Gasquet, he said: “The eye must grasp, bring things together. The brain will give it all shape.”

Early Still Life Paintings: These two earlier still-life paintings from the 1860s are much more classical in composition and style. Like Chardin, his objects are in a relatively straight line. A knife in the first work guides the eye into the painting. It’s function to cut the bread is plain. The cloth is definitely resting on a table as we see the outline of it, unlike his later paintings. In the second painting we see a difference. His brush strokes slash across the pears, thick paint bursting the edges in places. It looks hurried and tense as can be seen in his early landscapes and narrative paintings. Nothing quite like this had been seen before in his contemporary world. He would not find success until much later in his life when his still-life paintings were finally admired by the general public.

Cézanne painted the same object again and again and, as one looks through his work, they become recognizable quickly. By 1877, his compositions are still following the rules. Plate with Fruits and Sponge Fingers (1877) shows the straight line of objects and their relationships with each other in a realistic manner. The biscuits here are straightforward and meet our visual expectations, unlike the initial painting above from 1893. In the following years, Cézanne worked diligently and constantly to present all the dimensions of our sensations on multiple levels so that he and we could see his objects in a new way. This was true of all his subjects, whether in a landscape, a portrait, or a still life.

Atmosphere: According to Hajo Duchting’s 2003 book about Cézanne, the artist also wanted to: “reproduce the atmosphere of things. The starting point and central motif of his still-lifes are fruits.” To Gasquet, again he described his thoughts. “I decided against flowers. They wither on the instant. Fruits are more loyal. It is as if they were begging forgiveness for losing their color. The idea exuded from them together with their fragrance. They come to you laden with scents, tell you of the fields they have left behind, the rain that nourished them, the dawns they have seen. When you translate the skin of a beautiful peach in opulent strokes, or the melancholy of an old apple, you sense their mutual reflections, the same mild shadows of relinquishment, the same loving sun, the same recollections of dew…".

Still Life With Basket of Fruit (1888-1890) shows various everyday objects. The ginger jar, a cream and sugar set, and the warm colors and tone of this painting are immediately comforting to look at. The chairs, the tables, the paintings on the wall are homely and inviting. Knowing how he felt about the fruit that he painted offers more sensation. Imagine the smells, the feel of the fruit and the desire to be in that room. Still, he played with the balance. The basket is too large for the table. The handle is not where we would expect to see it. The ginger jar is tipped forward, the tabletops and legs are not matched. The cream and sugar lean to the left and the creamer handle like the basket handle is not quite “right”. A large pear on the left is extraordinary and seems to be a weight to hold the table down. He painted in yellow and blue tones, creating a canvas full of relationships that are on different planes and levels. It is sensual: a basket of fresh fruit from the orchards, with the promise of a delicious dish of fruit with cream and sugar soon to come. The distorted whole enhances the pleasure of the painting.

Cézanne’s Legacy: Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin have become known as the Post-Impressionists, the artists who transitioned from the Impressionist movement into the Modern Art period. Instead of portraying purely visual stimuli, Cézanne, in particular, was attempting to put his mind and his perceptions on the canvas and it was Paul Cézanne who Pablo Picasso singled out when he said of him, “he is the father of us all”.

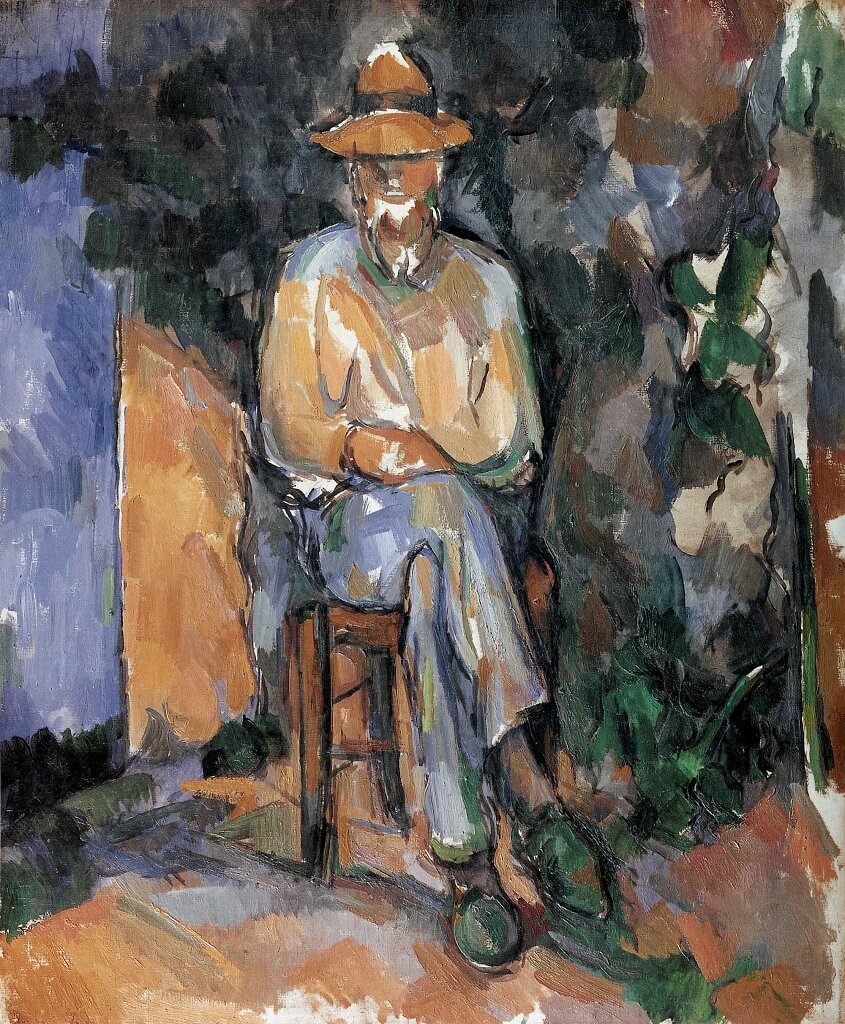

While Cézanne painted his colorful still-lifes, he continued to paint portraits and landscapes creating new views, different perspectives, and new ideas in all genres. He did say of himself, “I am the primitive of a new art”. He knew what he was doing was different. Portraits: Cézanne had hired Vallier to look after his garden in the Chemin des Lauves in 1902. He explained himself: “In today’s reality, everything is changing. But not for me. I am living in the town where I spent my childhood, under the eyes of people my own age, in whom I see my own past. I love above all things the way people look when they have grown old without violating tradition by embracing the laws of the present. I hate the effects those laws have.” His portraits are still, asking the viewer to stop and look at this man. In both paintings the man is at peace with himself, with who he is, with what he has done. The earth tones, the slashes of green, the deep dark of the foliage behind him and the wonderful straw hat all suggest peace with nature as well. Lurking in the back is the modern town as a reminder of the changes coming to the country. Cézanne’s colors flow, each brushstroke dependent on the next to provide the unity and harmony so spoken about in regard to his works. Each patch of paint reflects the one next to it as he builds his person in his environment. The Gardener Vallier (1906) seated on the chair is a looser composition, lighter and softer in tone. The painting has the same aura about it as its companion. The shapes formed by the color push towards the abstraction that followed. A frontal view with a slight turn to the right, allows us to see more of his body from differing angles. We can see these techniques in most of his works as he developed them over his lifetime.

Landscapes: Below are two landscape paintings by Paul Cézanne. In Gardanne (c. 1885), the building blocks are apparent and the Cubist beginnings are obvious. In Mont Sainte Victoire (1904), his style has developed much more. Cézanne was obsessed with Mont Sainte Victoire as he attempted to show every side and even the insides of this mountain. He painted it all his life and the painting below begins to take us into the world of abstraction. Each element in the painting is broken into pieces of itself but Cézanne has made certain they are still distinct.

Cézanne opened the door of possibilities for the Modern era artists with his unique use of colors and tones in his paints, the geometric shapes that were his building blocks and his compositions that changed the style of future art works. He perceived the world in a way not seen before and was brave enough to continue against all criticism and personal vitriol. Finally, he was at peace with his world and his work. He would be shocked now, to see the importance assigned to him.

Fun Fact: Recently, the Chief Conservator at the Cincinnati Museum of Art, Serena Surry, was examining, Still Life with Bread and Eggs (1865), as seen above. She became suspicious of what might be underneath and following x-rays, they found a “well defined portrait”. The staff are undertaking further investigation of the new-found work to find evidence as to whether it is a self-portrait of Cézanne or another individual.

Written by Carol Morse

References:

Where? Gallery 225 of the Art Institute of Chicago

When? 1864 What do you see? The sea as seen from Boulogne-sur-Mer, a French beach town on the English Channel, about 60 miles (100 km) South of the border between Belgium and France. Compared to seascapes by earlier artists, Manet used a high horizon line in his paintings, such that the biggest part of this painting is made up by the sea and the ships. Among the numerous sailboats is a steamboat which pollutes the view and the sky with its dark smoke. The steamboat is leaving from France to England through the English Channel. It leaves a visible trace in the water showing that it has to navigate its way through the asymmetrically scattered sailboats. Manet uses broad, horizontal brush strokes to paint the sea. Moreover, he uses blue and green pigments for the sea, and in some places, traces of the white canvas are still visible. These relatively bright colors make the sea the focus of the painting. The sea appears flat and calm, and this painting is the most abstract of the seascapes that Manet painted. Backstory: In July 1864, Édouard Manet went with his extended family on a vacation to a seaside resort in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. It was not just a vacation for Manet because he brought his brushes and easel and created several paintings of the sea and the ships. It was one of the first times that he worked on paintings outside, though he finished the painting in his studio in Paris. In this painting, he depicts an ugly steamboat among the more graceful sailboats. The first steamboats were developed by the end of the 18th century, and they were an important development as they could carry passengers and freight over large distances. In addition, they were an important innovation for the Navy, and they played an important role in the American Civil War. Seascapes: Sometimes referred to as Marine Art, the primary theme of the seascape is the sea. Its popularity has come in waves. For example, during the 17th century, seascapes were popular among Dutch artists. During the Dutch Golden Century, artists from The Netherlands painted scenes of sea battles. These paintings were very detailed and showed all the ongoing action of these battles. Seascapes became popular again among painters in the 19th century, especially after train connections between Paris and the French beaches were established around 1850. Besides Manet, painters like Courbet, Monet, Renoir, and Whistler created beautiful seascapes. However, J. M. W. Turner had already popularized the theme in the early 19th century. An example of a seascape painting by Turner is The Fighting Temeraire in the National Gallery in London, which he painted in 1838. Almost three decades later, Manet also started to paint several seascapes. One of his more popular seascapes is his 1864 painting of the Battle of Kearsarge and the Alabama in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The big difference between the 19th-century and 17th-century seascapes is that during the 19th century many details were left out of the paintings and the focus became the composition instead.

Who is Manet? Édouard Manet (1833 – 1883) was a French painter from Paris, France. He painted Steamboat Leaving Boulogne relatively early in his career. Manet’s paintings during that period were unconventional and were not well-received by art critics and the public. The Paris Salon, the biggest art exhibition in the world during the 19th century, rejected most of his works.

Manet also only sold few works and did not receive commissions. However, he persisted in his new style of painting during his career, relying on the financial support of his mother. Nowadays, his works are very popular. A good example is The Rue Mosnier with Flags from 1878 which was acquired by the Getty Museum in 1989 for $26.4 million.

Fun fact: Manet had always been fascinated by the sea. Following the suggestion of his father, he joined a training vessel for a three-month trip to Rio de Janeiro when he was 16 years old. He liked this experience and when he returned in 1849, he attempted the entrance exam to the Navy. However, he failed the entrance exam twice and decided that he wanted to become a painter instead – which was his first love – much to the dislike of his father.

Art lovers nowadays are happy that he became a painter instead. Not only are his works highly admired today, he also has had a major influence on the development of Impressionism, which has become one of the most popular painting styles ever developed. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us