|

Where? First floor, room 700 of the Denon wing in the Louvre

When? 1830 What do you see? This painting represents what a revolution feels like for the people involved. The woman in the center, referred to as Liberty, is holding the French tricolor. She stands on top of a barricade, which you can recognize by the pieces of wood and the cobblestones in the foreground. Liberty represents the struggle of the common people for freedom, but at the same time, she shows the energy and excitement that was part of a revolution. In her left hand, she holds an infantry musket. This is a rifle with a bayonet fixed to it, in case she needed to spear an enemy from close range. Liberty is depicted in a victorious pose, and she is showing her breasts to the people. Liberty is surrounded by a mix of people from the French society. On her right is a child brandishing a pair of guns. At her feet is a day laborer from the countryside wearing a blue jacket (notice the red, white, and blue pattern in his clothes, resembling the French flag). The man to Liberty’s left, with the black jacket and the top hat, is represents the middle-class people (some say it is Delacroix himself, but there is serious doubt about this claim). The man in white on the left is a factory worker holding a saber. There is a sharp contrast between the victorious people fighting for the freedom of France and the dead people in the foreground. In the bottom right, you can see a dead soldier and a guardsman. In the background, you can see the smoke of the cannons. In the top right background, the city of Paris is visible with the two iconic towers of the Notre Dame. Finally, the two spars of wood on the right show the signature of the painter, reading “Eug. Delacroix 1830.”

0 Comments

Where?

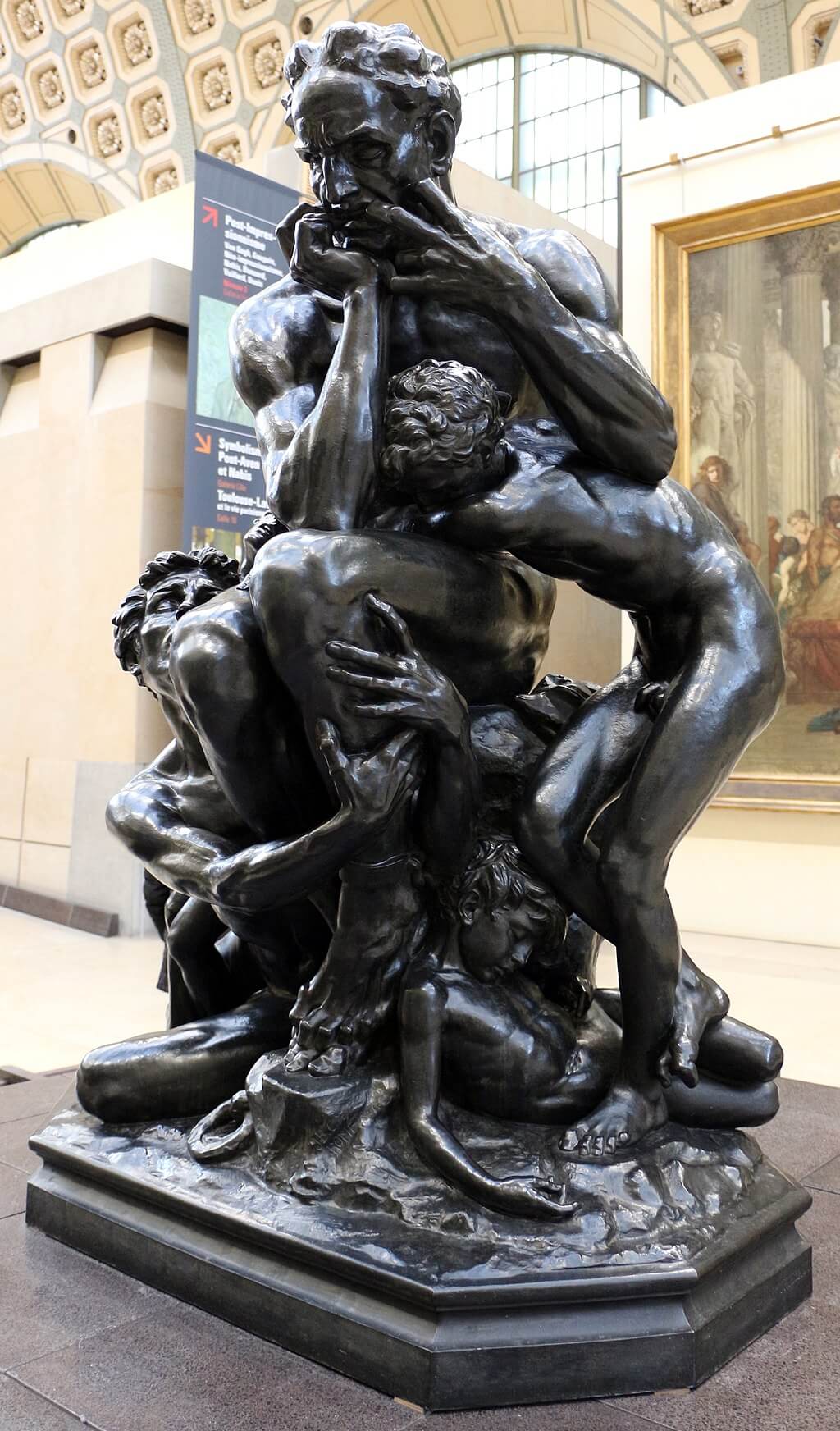

What do you see? Ugolino is sentenced to starve to death together with his children. This sculpture shows the moment that Ugolino considers cannibalism. He is depicted together with his four children, all naked, but is ignoring his children in this sculpture. He looks desperately in the distance and is biting his fingers and pulls his lip down with them. He holds his head in the palm of his hand. He is contemplating the consequences of his sins. He is sculpted as a muscular man even though he is starving to death. He is bending forward and has his feet on top of each other. The four children are in different states of suffering, and they beg their father to eat them such that he can stay alive. The oldest boy seems most energetic. He has his fingers in the flesh of Ugolino’s leg to emphasize his begging. The second oldest son on the right is also holding his father with both hands. The second youngest son on the left sits on top of his oldest brother and has already lost most of his remaining energy. He has his left arm on his father’s leg. The youngest son is on the bottom right and while he is the only one with a peaceful expression he appears already dead. Carpeaux is telling a story with this sculpture, something that is very difficult to do in a sculpture. He was able to sculpt the skin, muscles, and veins very realistically and to express the strong emotions of the different subjects. The more you look at the details of this marble statue, the more "alive" the subjects become. For example, you can see Ugolino’s agony by the curve in his spine, and even the toes of Ugolino are curled to show his agony. Different versions of this statue: Several sculptures of Ugolino and His Sons have been made. Carpeaux got the idea of creating a sculpture of Ugolino and his sons in 1858. He started by making a plaster version of it, which he completed in 1861. This version is in the Petit Palais in Paris. After that, in 1862, he created a bronze version which is now in the Musée d’Orsay. The final version he created was the marble version in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rodin was inspired by the sculptures of Carpeaux and, in 1881, he made a plaster version of Ugolino and His Children which is in the Musée Rodin in Paris.

Backstory: This work is created under the supervision of Carpeaux and is based on canto 33 of Dante’s Inferno (which is the first part of the Divine Comedy). In this book, Dante travels through the nine circles of hell. Each circle contains people who are convicted in hell for a different sin. In the ninth circle, he meets Count Ugolino della Gherardesca (c. 1220-1289), who was convicted for treachery. In 1288, Ugolino worked together with the archbishop Ruggieri to take control of the factions in Pisa. However, in this process, Ruggieri betrayed him and locked Ugolino up in prison.

More precisely, Ugolino was imprisoned together with his children and grandchildren in a tower and condemned to starve to death. His children begged Ugolino to eat them to survive, and his hunger was stronger than his sadness about his dying children. It is unclear whether Ugolino ate his children in the end. In Dante’s story, Ugolino’s eternal punishment in hell is that he is stuck up to his head in the icy waste of Antenora which is the punishment for political traitors. Meanwhile, he is chewing the head of Ruggieri (the person who betrayed him in real life) who is also stuck in the ice. Who is Carpeaux? Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1875) was born in Valenciennes, France and died in Paris. In 1854, he moved to Rome, where he got inspired by the Renaissance artists such as Donatello, Michelangelo, and Del Verrocchio. Carpeaux suffered a lot during his life, both mentally and physically, and you can see that back in some of his extreme works. His sculptures are known for the emotions they evoked among the viewers, and he distinguished himself with his style from his contemporary colleagues. He is considered one of the greatest sculptors of his time, though most people consider Antonio Canova (who was born before him) and Auguste Rodin (who was born after him) to be even better. Fun fact: The sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art is placed very close to the entrance of the Petrie Court Café. It is ironic that this sculpture with the theme of starvation is so close to the Café. While this may be a coincidence in itself, another statue that deals with starvation is also close to the Café. Rodin’s bronze The Burghers of Calais sculpture shows six leaders of the city of Calais who are starving and have a rope around their neck as they will be executed soon. The marble statue of Carpeaux is also next to the statue of Perseus with the Head of Medusa by Antonio Canova.

Where? Room 64 of the Prado Museum

When? 1814 Commissioned by: The Spanish government What do you see? A scene of a street fight. Napoleon’s Turkish soldiers, the Mamelukes, ride on horses, arms raised with swords. They are recognizable in their turbans and black uniforms. Some of them wear blue shirts and red pants. On the ground are the outnumbered citizens of Madrid. They are peasants and common people recognizable by the dull rags that they wear. A man that appears to be a Spanish soldier stands on the right side in a black uniform. He points his gun towards one of the Mamelukes. In the foreground, a man stabs a white horse as another man on the left raises his arm to stab its rider. Beneath the horse are two dying rebels. Behind, a peasant tackles a Mameluke, jumping off the ground to attack. The numerous blurred faces in the middle ground add to the chaos of the scene. Although the scene looks like a Spanish triumph, the reality of the story is not so. Backstory: This painting commemorates a true historical event. In this work, Goya shows one of many street fights that broke out on the second of May, 1808, when Spanish citizens rebelled against the French occupation. The Spanish people that rebelled during that day were executed by French firing squads on the next day, and Goya captured that event in a separate painting called The Third of May 1808 which is also in the Prado Museum. The painting of The Second of May 1808 is crammed with the bodies of Mamelukes, Spaniards, and horses that tangle to make for a very chaotic scene. The moment is dramatized with the harsh light on the white horse in the center of the painting and the subtle diagonal drawn from the cadaver (bottom left) to the two soldiers with raised weapons (right of center). The work also uses lighter colors and bright reds that put it in direct opposition to The Third of May 1808, which uses darker tones. Goya puts an emphasis on the sacrifice of the Spanish rebels, showcasing their heroism.

May 2, 1808: This was the day that many citizens of Madrid rebelled against the French occupation. Crowds assembled around the Royal Palace of Madrid to protest the French occupation. The French soldiers opened fire on the crowds, triggering street fights and rebellion in other parts of the city. The French armed forces outnumbered the Spanish citizens. When the conflict had subsided, hundreds of Spanish citizens had died. Many survivors were taken prisoner for execution the next day.

May 3, 1808: The day after the Spanish rebelled against the French army, the rebels were executed by French firing squads. Many surviving Spanish rebels were gathered and shot in several locations in Madrid. Supposedly, most of the executed rebels were peasants, artisans, and beggars. About one hundred deaths by firing squads were reported. Goya captured the events on this day in his painting The Third of May 1808, which is also in the Prado Museum. Who is Goya? Francisco Goya was born in 1746 in Fuendetodos in the Northeast of Spain and died in 1828 in Bordeaux, France. He studied drawing and painting in Zaragoza and joined the studio of José Luzán. Later, he studied under Francisco Bayeu Subías who led him to work on decorations for the royal palace. Goya married Subías’s sister and traveled to Italy after failing in two drawing competitions at the Real Academia des Bellas Artes in San Fernando. Eventually, Goya was appointed painter to the Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid. His work was reminiscent of Rococo art and focused on day-to-day events. As his work gained more attention, Goya rose to the position of court painter to King Charles III and Charles IV. His style was cheerful and warm and included paintings like The Parasol in the Prado Museum. But around 1793, he fell ill and became deaf. After this, Goya’s work became filled with darkness, ghosts, and monsters. An example of such a dark painting is Saturn Devouring His Son, which is also in the Prado Museum.

Fun fact: During the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939, the collection of the Prado Museum was moved to the League of Nations in Geneva. The truck transporting some of Goya’s works was caught in an accident as it was passing through Girona. The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808 were stored together, and both suffered quite a blow. However, The Second of May 1808 suffered more damage. In the process, the canvas of this painting was damaged. Small pieces of the canvas fell off the left side and were lost on the road. Tear marks and scratches are still visible on the left side of the work despite restoration efforts in 1941, 2007, and 2008.

Where? Room 64 of the Prado Museum

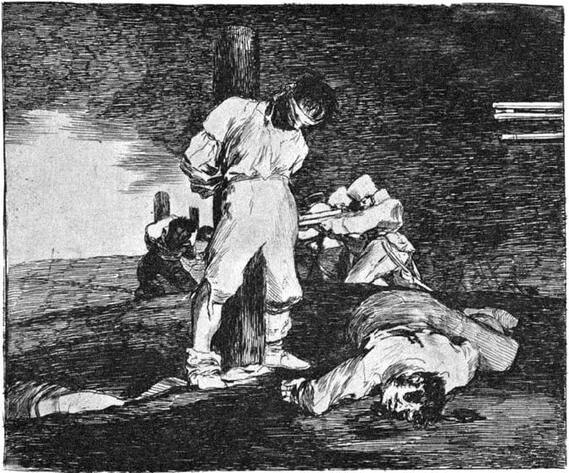

When? 1814 Commissioned by: The Spanish government What do you see? A group of French soldiers on the right point their rifles at a Spanish peasant dressed in white. The French firing squad is about to execute the peasant who stands against a hill with his arms raised like a Christ figure in surrender. At his feet are some of his comrades who have been slaughtered by the firing squad, their blood still running on the dirt. And surrounding them are other people that are next in line to face the firing squad. Some of them cover their eyes as they do not want to witness the gruel scene in front of them. Among the people surrounding the man in white is also a bold-headed monk. He is directly to the left (from our point of view) of the man in the center, and he has his hands clasped in prayer, avoiding the eyes of the soldiers. Backstory: This painting is a commemoration of a true historical event, Napoleon’s French army invading Spain. This painting shows a particular scene that occurred on May 3, 1808, when the French army decided to execute Spanish citizens that rebelled against them. Francisco Goya was deeply affected by this series of events and decided to create this painting to show the injustice of the French army’s actions. Goya has dramatized the moment. The square lantern in the center pours bright light onto the rebels on the left and the man dressed in white. Goya gives him a Christ-like aura with his arms raised in golden light. The man is made into a martyr while the French soldiers are left anonymous and thus soulless. May 2, 1808: This was the day that many citizens of Madrid rebelled against the French occupation. Crowds assembled around the Royal Palace of Madrid protesting French occupation. The French soldiers opened fire on the crowds, triggering street fights and rebellion in other parts of the city. The French armed forces outnumbered the Spanish citizens. Goya captured the events on this day in his painting The Second of May 1808, which is also in the Prado Museum. The painting depicts the Mamelukes (Napoleon’s Turkish soldiers) in a street fight with Spanish rebels. When the conflict had subsided, hundreds of Spanish citizens had died. Many survivors were taken prisoner for execution the next day.

May 3, 1808: The day after the Spanish rebelled against the French army, the rebels were executed by French firing squads. Many surviving Spanish rebels were gathered and shot in several locations in Madrid. Supposedly, most of the executed rebels were peasants, artisans, and beggars. About one hundred deaths by firing squads were reported.

Who is Goya? Francisco Goya was born in 1746 in Fuendetodos in the Northeast of Spain and died in 1828 in Bordeaux, France. He studied drawing and painting in Zaragoza and joined the studio of José Luzán. Later, he studied under Francisco Bayeu Subías who led him to work on decorations for the royal palace. Goya married Subías’s sister and traveled to Italy after failing in two drawing competitions at the Real Academia des Bellas Artes in San Fernando. Eventually, Goya was appointed painter to the Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid. Goya's work was reminiscent of Rococo art and focused on day-to-day events. As his work gained more attention, Goya rose to the position of court painter to King Charles III and Charles IV. Around this time, he began to travel Andalusia to study realism. When he returned from his trip, he had fallen ill and gone deaf. Before the decline of his health, much of Goya’s work had been cheerful and warm. After losing his hearing, Goya’s work became dark and filled with monsters, darkness, and ghosts. Witches’ Sabbath in the Prado Museum is an example of such a dark work. It is part of his series of fourteen Black Paintings.

Fun fact: Before painting The Third of May 1808, Goya had worked on a series called The Disasters of War. These gruesome prints showed the violence, gore, and fear that comes from war. Without taking a side in the conflict, Goya expressed great anti-war sentiment. The prints were not published until decades later.

Where? Gallery 251 of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

When? 1840 What do you see? Vibrant colors and bright light make for what appears to be a beautiful sunset over the sea. However, upon further inspection, the scene is actually a dark one. The foreground is littered with the bodies of drowning slaves. Their chained arms reach out of the water to try to survive. And on the bottom right, we can see a single leg sticking out of the water. The slaves are not going to survive as a school of fish are already biting away at their flesh, and some birds are arriving to get their share as well. Behind the drowning slaves, a ship is caught in a storm, waves crashing against its sides as it steers away from the slaves. Backstory: This painting is also known as Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and the Dying – Typhon Coming On. Turner based The Slave Ship off of a true story to illustrate the realities of the slave trade. In 1781, Luke Collingwood, the English captain of the slave ship Zong, set sail with 470 slaves and an inadequate amount of food and water. When crew members and slaves began to fall ill, Collingwood threw 132 slaves overboard to save his ship. He would also receive insurance money for the slaves “lost at sea.” Turner painted the aftermath of this terrible act and adds a touch of justice by sending the ship into a violent storm in the background. English Abolitionism: Following the Zong Massacre in 1781, Granville Sharp, a leading abolitionist, made an attempt to charge Collingwood with murder. However, because slaves were considered commodities like wood and tea, the captain was ruled innocent. While this may seem like a failure, the Massacre actually raised awareness of the anti-slavery movement and inspired more Englishmen to join the cause. Eventually, slavery was abolished in England in 1833. Who is Turner? Joseph Mallord William Turner was born in 1775 in London where he died in 1851. He was an English romantic painter who attended the Royal Academy of Arts in London and studied with Thomas Malton. His early works were topographical watercolor paintings and engravings that appeared in books and magazines. In hopes of achieving something greater, Turner completed his first oil painting, Fishermen at Sea, which was displayed at the Royal Academy in 1796. The work received high praise and got him elected as an associate of the Royal Academy. Around this time, Turner made many copies of the works of landscape painter John Robert Cozens. Cozens’s more imaginative style encouraged Turner to experiment with a more whimsical and romantic style that eventually brought him to fame. Turner’s landscapes show a mastery of many different terrains and expertise in color and light that feels somewhat like that of the impressionists of the later 19th century. Among his famous works are his two version of The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons. One version is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the other in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Fun fact: When Slave Ship was first displayed at the Royal Academy, it was accompanied by an excerpt of a poem that Turner wrote. The long poem, “Fallacies of Hope,” was never finished and published. Here is the excerpt:

“Aloft all hands, strike the top-masts and belay;

Yon angry setting sun and fierce-edged clouds Declare the Typhon’s coming. Before it sweeps your decks, throw overboard The dead and dying - ne’er heed their chains Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope! Where is thy market now?”

Where? First floor, room 700 of the Denon wing in the Louvre

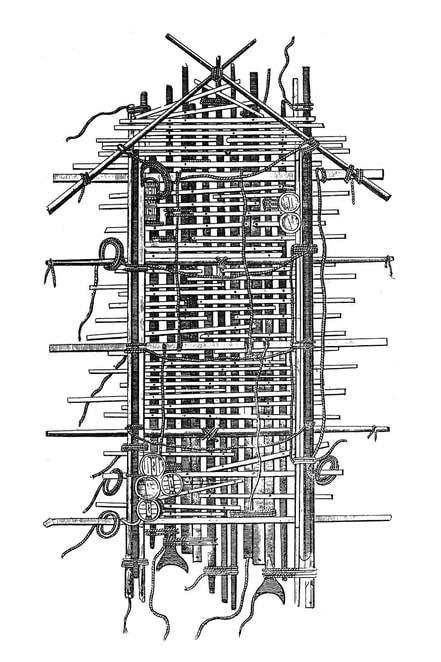

When? 1818-1819 What do you see? A moment about two hours before the survivors of a shipwreck are rescued. After spending 13 days on a raft on the open sea – surrounded by big waves – the surviving members of The Medusa notice a ship on the horizon (see the tiny ship on the horizon above the man on the right with a red garment around his upper legs). Some of the survivors frantically try to get the attention of the ship. However, they are unsuccessful at first and only two hours later the ship locates the raft and the survivors are rescued. The improvised raft carries 20 people. It seems that there are four or five dead bodies, mostly in the foreground. The survivor that reaches highest is an African man. Géricault gave this man a very prominent place as a political statement against slavery. The man stands with his right leg on a barrel of wine, which is the only liquid they had to drink on the raft. In the left foreground, a father with a red cloth holds the dead body of his son in front of him. What it the Raft of the Medusa? The Medusa was a French warship. In 1816, it left from Rochefort, France, in the direction of Senegal, where the British would hand over the port of Saint-Louis to the French. The ship carried 400 passengers. Navigational mistakes caused the ship to run aground in shallow water about 30 miles (50 km) from the coast of Mauritania. The ship was damaged, and the passengers needed to be evacuated. However, there were not enough lifeboats to carry everybody. The majority of passengers used the lifeboats to get to the African coast. About 150 people got on an improvised raft of 66 ft (20m) long and 23 ft (7m) wide (see the picture below based on a drawing of one of the survivors). There was very little food on the raft, it was half underwater, and could not be steered. So, these people were lost at sea. Many of them died because of a lack of food, fights, suicide, or cannibalism. When the raft was discovered by a rescue ship 13 days later, only 15 people were alive (of which five died within days after their rescue). Two survivors wrote a book about their experiences and the full text of that book is available for free.

Backstory: Within two months of the rescue, the first accounts of the brutal journey of the raft of the Medusa appeared in French newspapers. These stories caused a big scandal in France and the government tried to cover it up unsuccessfully. Géricault got inspired by these stories and wanted to start a painting about it.

Géricault spoke to two survivors to get an even better idea of what they experienced. He picked a specific moment from their survival story as the subject for this large painting. He also tracked down the carpenter that helped to build the raft from the wooden deck of the Medusa and asked him to create a smaller-scale replica in his studio. Many of the preparatory sketches by Géricault for this painting are still available. A more elaborate sketch that is also owned in the Louvre is shown below. All this preparation resulted in a brilliantly-executed painting. According to many, this is the most famous painting from the Romantic art period.

Moral: The moral is one of despair, hope, and persistence. After 13 days, the people on the raft finally see a ship that could rescue them. However, the ship does not seem to see them. Some people in this painting are still trying to get the attention of the ship, while others have already given up, turned around, and sit down in disappointment.

Who is Géricault? Jean-Louis André Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) was a painter and lithographer from France. He is one of the founders of Romanticism, an art movement that was further developed by Eugene Delacroix. While Géricault received some formal training, he was largely self-educated. He got his inspiration from Michelangelo, Gros, and especially Rubens. Géricault was a specialist in painting horses. His first masterpiece, The Charging Chasseur, which is also in the Louvre, was accepted for the Paris Salon of 1812. Two years later another painting of him got accepted by the Salon, entitled The Wounded Cuirassier, which is on display both in the Louvre and in the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York.

Fun fact: The Raft of the Medusa painting was a controversial one and Géricault was aware of that. The painting was a political statement against the government who had failed in appointing a proper captain to the Medusa and, subsequently, tried to cover up their mistakes in handling the aftermath.

Géricault used a canvas of 23.6 ft (716 cm) wide and 16.1 ft (491) cm high, making the figures in this painting larger than life-size. He knew that he would not sell this painting as it was too big for a private home and the government would not buy it. The painting got accepted for the 1819 Paris Salon and immediately went viral, becoming the talk of the town. As expected he did not sell it, but he earned some money when the painting toured various exhibitions in Europe, where the painting was received positively. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster.

Where? First floor, room 700 of the Denon wing in the Louvre. A smaller version is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art but is currently not on display.

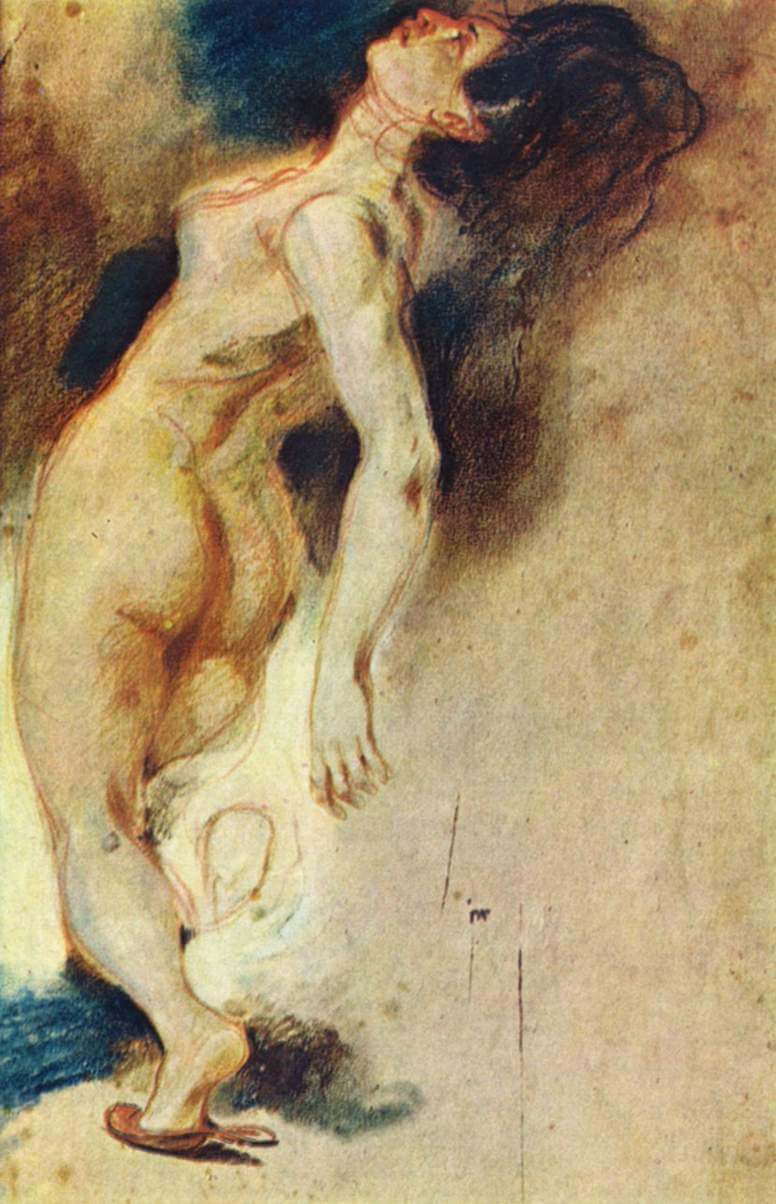

When? The original is from 1827, and the smaller replica is from 1844. What do you see? In the center, King Sardanapalus of Assyria, dressed in white, lays in his bed which is covered with bright red sheets. On the front corners of his bed are two large elephant heads. His bed stands on top of a large pyre. You can see some woodblocks making up the pyre behind the black slave in the left foreground and on the bottom right. While rebellion forces surround his palace, Sardanapalus orders his eunuchs and palace officers to cut the throats of his mistresses. He did not want anyone or anything that gave him pleasure during his life to survive him. He has a calm and disinterested expression which contrast strongly with the cruel scene around him. Notice also that all mistresses and Sardanapalus wear expensive jewelry as the king also wanted his royal possessions to be burned with him on the pyre. On the bottom right is also a collection of crowns and jewelry that are about to go down.

Backstory: Delacroix got his inspiration for the theme of this painting from a play written by the English poet Lord Byron, who in turn was inspired by older texts on the story of Sardanapalus. In 1821, Lord Byron wrote a play called Sardanapalus: A Tragedy (Amazon link to this book) which describes the crazy story of the death of Sardanapalus. In preparation for this painting, Delacroix also consulted some older writings on the death of Sardanapalus. He combined all these sources to create a unique story on the death of Sardanapalus. We can still identify some figures in this painting based on Lord Byron’s play. For example, the man on the left removing a spear from his chest is Salemenes, the brother-in-law of Sardanapalus. He just came back from the battlefield and will die after he removes the spear. And the woman lying on the bed is Myrrha, the lover of Sardanapalus. According to Lord Byron’s story, she was the only one with Sardanapalus on top of the pyre. Who is Sardanapalus? According to the Greek writer Ctesias, Sardanapalus lived in the 7th century BC. He was the last king of Assyria, which was a very large empire in the Middle East between the 25th and 7th century BC. He lived an extremely luxurious life and was very lazy. According to Sardanapalus, the main purpose of life was physical desire. He followed his own advice, dressed in woman’s clothes, wore makeup, and was surrounded by many male and female mistresses. As many people got annoyed by his lifestyle, a group of rebellions formed to defeat Sardanapalus and his troops. Sardanapalus went down in a typical fashion. As some point during the war with the rebellions, he thought that he had defeated the rebellions and started a big party. However, the rebellions came with reinforcements and defeated Sardanapalus, leading to the end of the Assyrian empire. Before he got caught, Sardanapalus burned himself together with many of his eunuchs and mistresses, and most of his royal possessions. Who is Delacroix? Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) was the leader of the Romantic painters in France. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was the main artistic rival during his life. Whereas Ingres was the leader of the school of Neoclassical painting, Delacroix believed in the Romantic style and was inspired by artists like Rubens, Tintoretto, and Veronese. The style of Delacroix can be characterized by an emphasis on using colors and depicting emotions, and not on providing a clear composition and shapes of the people in his paintings. In 1830, he painted his most famous work, Liberty Leading the People, which is on display in the Louvre as well. The work of Delacroix has been important for the development of Impressionism later in the 18th century. Artists like Degas, Manet, and Renoir greatly admired the work of Delacroix.

Fun fact: This painting is the largest uncommissioned by Delacroix. He had high hopes of this work and created many sketches that are still available for this painting. Below are two pictures of sketches he made that are in possession of the Louvre.

The painting was first exhibited in the Salon of 1828 in Paris. The painting got many negative reviews. One viewer went so far as threatening to cut off Delacroix's hands such that he could never paint again. There were several reasons for these negative reactions, such as the messy composition and incoherent use of colors. Whereas the French State bought earlier paintings of Delacroix, they did not buy this one. Instead, Delacroix took it back to his studio where it stayed until 1845. He only sold the painting after he made a much smaller replica of the painting owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The larger painting was not on public display until 1921 when the Louvre bought it. Nowadays, this painting is highly appreciated. Looking back, it is one of the early Romantic paintings. Whereas people in the early 19th century were still used to the clarity of the Neoclassical paintings by Ingres and colleagues, the Romantic paintings focused on showing emotions in a more chaotic setting. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us