|

Where: Room 15 of Level 0 of the British Museum

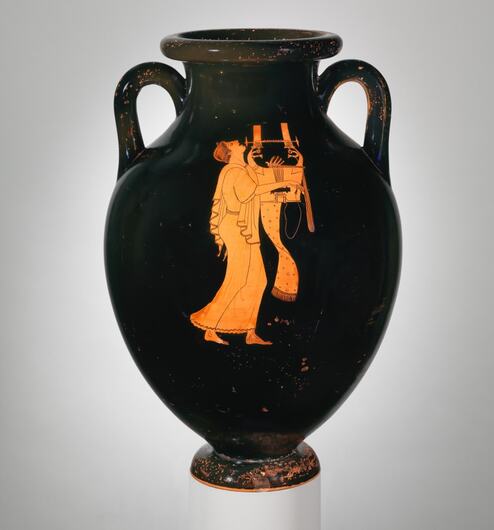

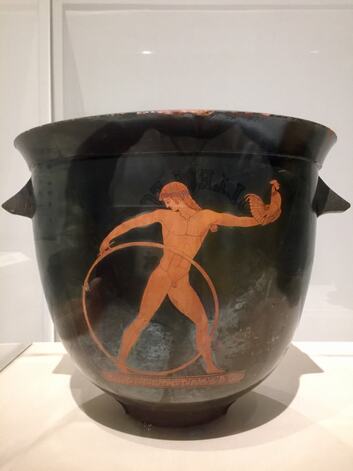

When: Probably between 490 BC and 460 BC What do you see? A monumental vase with two mythological scenes painted on the upper part, the neck. The vase is a masterpiece of the red-figure technique and one of the iconic examples of Athenian pottery. The shape of this vase is called a volute krater (named after the spiral handles resembling the volutes of the Ionian columns).

Background: This vase is one of the early works of the Berlin Painter. Carol Moon Cardon situates it in the second group of vases from his early period, falling between 500-490 B.C. The timeframes are often tentative, depending on the source or criteria by which scholars assign them. More generally, its place in art history falls into the Late Archaic period (circa 500 to 470 B.C.) There are four preserved volute kraters by the Berlin Painter, all in the red-figure technique. The London krater is unique for a variety of reasons; its architectural design resembling the temple is among the most prominent of those. The fact that the painter decided to leave the entire belly of the vase black while placing the narrative and ornamentation on its extremes speaks of his highly sophisticated approach to design and the interpretative role he attached to imagery.

Red-figure technique: The red-figure painting technique appeared in Athens around 520 B.C. in what is known as the Pioneers’ Group—possibly the longest lasting and most influential red-figure workshop known. The Berlin Painter was possibly the student of one of the three most important of the Pioneers, Phintias. Prior to that, until about the second half of the sixth century B.C., the world of the vase painting was dominated by the black-figure technique.

The red-figure technique was actually simpler than the black-figure technique. The main principle in both was the skillful regulation of the flame and oxygen flow through the oven where the vases were fired to assure the proper oxidization of iron, which, in turn, allowed the painter to achieve the desired color. The black-figure technique rested, in principle, on adding varnish to the pre-contoured shapes on the surface of the vase to create fully developed objects and figures, which turned black upon firing; the red-figure technique was the reversal of the process. Who is the Berlin Painter? Very little is known about the Berlin Painter in terms of the biographical information. It was not common for the vase painters to sign their names at that time. Interestingly, the Berlin Painter inscribed the names of his characters on the London krater. And yet, we do not even know his real name since none of the works attributed to him indicates it. The nickname “The Berlin Painter” was given to him by the prolific scholar, Sir John Beazley, who attributed the makers of some 30 thousand items of Athenian ceramics. The nickname is based on the amphora located in Antikensammlung in Berlin, excavated in the Etruscan city, Vulci. This amphora served as the “mother-work” of the Berlin Painter--the vase to which other found works and fragments were compared in terms of stylistic details, resulting in matching them to the hands of one maker. Some of the stylistic details of the Berlin Painter, which revolutionized the red-figure technique, include:

What we know about him as a person, we can only guess from the themes he chose for his imagery; he was fond of animals and nature, probably liked poetry and city festivals and, of course, gave homage to the gods. He avoided the otherwise common themes of bloody combats and gory scenes, or those of debauchery and drunkenness. Even his depictions of satyrs seemed to emphasize their human nature over the animalistic. The Berlin Painter just seems like a mellow, content man. Other works by The Berlin Painter: In 1911, Beazley assigned 38 vases to the Berlin Painter (“master of the Berlin amphora”) and outlined the characteristics of the Berlin Painter’s renderings. His drawing style was described in 1922 and by 1925 there were already 148 vases attributed to the artist. As of today, over 400 works of pottery and fragments are attributed to the Berlin Painter. Because of their masterful artistry, they are highly appreciated and sought by the world’s museums. In the Gregorian Etruscan Museum in the Vatican Museums, there is the beautiful hydria with Apollo sitting on the winged tripod, playing the lyre, as two dolphins below make their way back into waters. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has 13 vessels. Among them is another hydria, featuring Achilles slaying Penthesilea, the queen of the Amazons. This museum has arguably one of the most exquisite of all vases by the Berlin Painter, the type C amphora with the beautiful walking-singing citharode—youth playing the kithara—on one side and the contest judge on the other side. The Louvre has the largest collection of his vases, for a total of 36. The only cup known to be painted by this artist (although debates over the attribution continue) is in the Agora Museum in Athens. It is called the Gorgos Cup, after the potter Gorgos, who provided the vessel to be decorated. The name "Gorgos" as the maker of the vessel is inscribed on the cup. While some painters were also potters of the vases they worked with (and it is possible the Berlin Painter was among them in some instances), the transition from potter to painter was not at all automatic. There are also the Panathenaic amphorae painted by the Berlin Painter. Those were the vases that were filled with olive oil and given as prizes to winners of the Panathenaic Games. They were always traditionally done in the black-figure technique. Only highly esteemed painters were commissioned to provide those. Out of 21 vases painted by the Berlin Painter in the black-figure technique, possibly only two are not the Panathenaic amphorae (a fragmented amphora Type A in New York and a hydria in Frankfurt). While vases, in general, were popular in antiquity and were given as burial offerings to go with the departed close ones, only the wealthy could afford to have a vase decorated by, say, the Berlin Painter or other artists of high esteem. The amphorae given to victors of the games were a sign of the prestige of the artist whom they were commissioned to.

Legacy: There were three immediate students of the Berlin Painter, who were all very important and painted a large number of vessels: The Providence Painter, Hermonax and The Achilles Painter. The last of them, along with his own student, the Phiale Painter, closed the workshop of the Berlin Painter in 425. Although the workshop closed, many features of the Berlin Painter’s innovative style remained with generations of vase painters.

The students of the Berlin Painter and other followers who came even later into the vase painting world (the Harrow Painter, the Tithonos Painter, the Painter of the Yale Lekythos, Alkimachos Painter, just to name a few) carried on the legacy of the master by either adopting his ornamentation style, features of the design (the “less is more” on the vase), or took up shapes which were not popular among the red-figure artists before the Berlin Painter. The Berlin Painter was not only the master of the already existing technique but developed it as well as expanded the repertoire of shapes which began to be painted in the red-figure technique. He was not just the master of his technique but a thinker and inventor.

3 Comments

Wai Laam Lo, CC BY-SA 3.0

Where? Room 18 of the Uffizi Museum

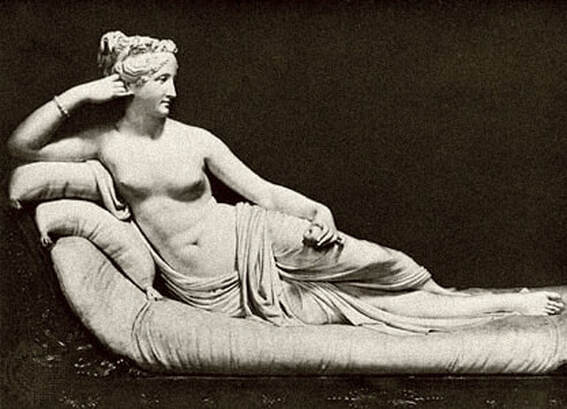

When? Between the third and first century before Christ Commissioned by? Unknown What do you see? A life-size marble statue (about five feet tall or 155cm) of the Greek goddess Venus. At her feet is Cupid (the god of Desire, erotic love, attraction, and affection) riding a dolphin. Venus is depicted in a fugitive pose after arising from the sea. The statue was considered one of the most erotic statues in the world due to her almost perfectly sculpted buttocks (which you cannot see, unfortunately). While her arms are partly covering her breasts and pubic area, it actually draws the attention to these parts of her body. Backstory: The origins of this statue are unknown, and thus we don’t know who sculpted her. It is the oldest statue in the Uffizi and is referred to as Venus de’ Medici because the Medici family acquired it in 1677. The statue was initially displayed in Rome, but Pope Innocent XI decided that it should be moved to Florence. Pope Innocent XI was a deeply religious man and decided that such a notorious naked statue did not belong in Rome. The statue was originally colored. However, over time the statue lost its color and experts thought that the colors were not part of the original. So, in the 18th-century acids were used to remove the last traces of color from the statue. Recent microscopic research has shown that the statue was colored originally. The original color of her hair was gold, she had red lips and her ears were pierced for earrings. This marble statue is a copy of an original Greek statue of Venus in bronze. The Venus De’ Medici is one of the most copied statues of all time (for example, there is one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York). Interestingly, the Venus de’ Medici, with Cupid riding a dolphin is not tied to any known mythological story, which adds to the fascination and speculation about this statue. Symbolism: The size of Venus is enormous compared to the small Cupid and the dolphin at her feet to give the impression that Venus is giant. The somewhat apologetic pose of Venus (covering her breasts and pubic area) and the dolphin at her feet make it likely that she got somewhat surprised when arising from the sea. Who is Venus? Venus is the Roman goddess of love, beauty, sex, fertility, prosperity, and desire. Venus is also known in the Greek mythology as Aphrodite. Together with the Mars, the god of war, she is the parent of Cupid. The ancient Romans also considered Venus as the goddess of the gardens, and this makes her a popular subject for statues placed in gardens. Over time many statues have been made of Venus, often as an excuse to depict nudity. A well-known example is the Venus Victrix of Antonio Canova which can be admired nowadays in the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

Why Venus? Venus was admired by the Romans and Greeks as she represented love and sexuality. This statue of Venus was heavily inspired by the life-size statue Aphrodite of Cnidus (or Knidos), a famous statue from the fourth century before Christ. These life-size statues of a naked Venus were considered to be very attractive to men in ancient times.

Fun fact: The statue has an inscription at its base reading ‘CLEOMENES SON OF APOLLODORUS OF ATHENS’. However, this inscription is not original as the base with the inscription was broken. The current inscription was added to it in the 17th century. It seems highly unlikely that Cleomenes created this sculpture as he was not a very good sculptor. In the 17th and 18th century it was common practice to add the name of Cleomenes to statues of mediocre quality to enhance the value of those statues. The Venus de’ Medici sculpture, however, is more in line with the work of Praxiteles who created very elegant and graceful statues around the time that this statue was made, but there is not much other evidence to confirm this.

Written by Eelco Kappe

Where? The Octagonal Court of the Museo Pio Clementino in the Vatican Museums

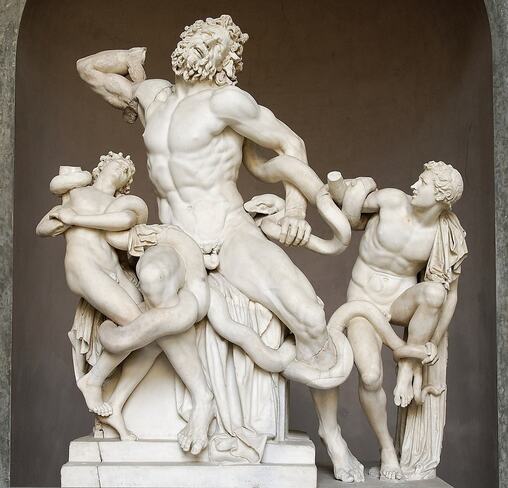

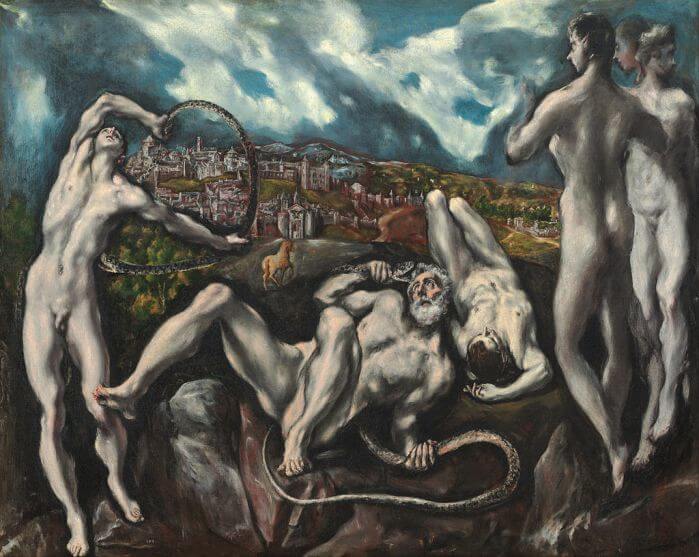

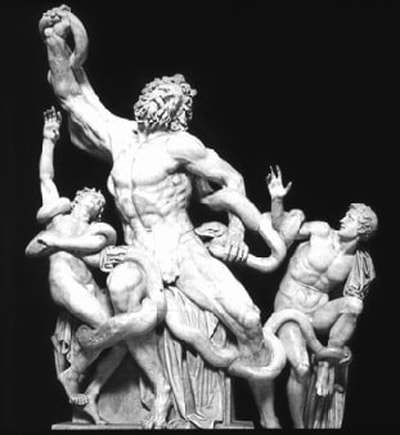

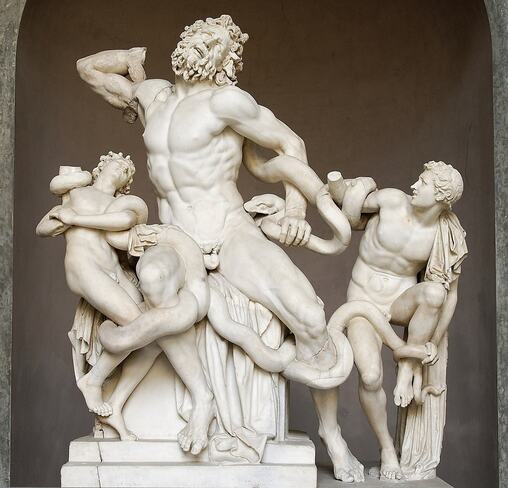

When? Uncertain, but estimates range from the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD. By who? Unclear, but probably this is a Roman copy of an ancient Greek original in bronze. Some people suggest that it was made by the three Greek sculptors Hagesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus. What do you see? This life-size statue is made of seven different blocks of marble and shows Laocoön and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, being attacked by two sea serpents. Laocoön sits on an altar and is sculpted as a very muscular man. He strains every muscle that he has to escape from the serpents. The oldest son on the right seems to break free from the serpents and looks at his brother and father. Laocoön and the youngest son on the left are in big trouble, and their faces express their struggle. The youngest son seems to cast a last glance at his father, but he looks to be (almost) dead already. Notice that the serpents are trying to kill Laocoön and his sons both by constricting and biting them. You can see the head of one of the serpents next to the left hand of Laocoön. You can also see that a few pieces are missing from this sculpture.

Who is Laocoön? According to Greek mythology, Laocoön was a Trojan priest. There are various accounts of his story. Virgil describes the most popular version in the second book of the Aeneid. According to him, when the Greeks left Troy, they left as a gift a very large wooden horse in front of the gates of Troy. Laocoön suspected that this horse was a trick of the Greeks and tried to convince the people of Troy not to accept the gift.

To prove that the horse was a trick, Laocoön struck the horse with his spear to show that it was hollow. Poseidon and Athena then punished him for his interference and Laocoön and his two sons were attacked and killed by two sea serpents named Porces and Chariboea. The Trojans interpreted this event as a sign that the horse was not a trick and they took the horse into their city walls after which the Greek came out of the horse during the night and defeated the Trojans. Copies: Many copies of this statue have been made and can be found across the world. A well-known copy is the marble version by Baccio Bandinelli in the Uffizi Museum in Florence. Another bronze version made by Francesco Primaticcio for King François I of France is in the Louvre. Jean Baptiste Tuby made a copy for the Park of the Château de Versailles in France. The Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia, has a terracotta version of this sculpture by Stefano Maderno. Some other places that have a copy of this statue are the Mannheim Palace in Germany, the Archeological Museum of Odessa in Ukraine, Houghton Hall in England, and the Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes in Greece. This statue has also inspired many other artists to depict the story of Laocoön. For example, El Greco created a painting of Laocoön that is now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Several parodies of this sculpture have also been made over time. For example, Niccolò Boldrini made a woodcut around 1540 for which he copied a drawing of Titian in which monkeys replace Laocoön and his sons.

Fun fact: The statue misses a few limbs and parts of the serpents. Over time, the missing parts were added to the sculpture and sculptors, including Antonio Canova did various restorations. The right arm of Laocoön was already added in the 16th century, but there was quite some discussion on whether the arm would be straight up or bent back over the shoulder (which Michelangelo suggested). The experts chose that the arm would be straight up and you can see in the picture how the statue looked before 1960.

In 1906, an archeologist found a right arm of a sculpture which he thought could be the missing right arm of the Laocoön sculpture. He donated the arm to the Vatican Museums, but only 54 years later the museum verified that it was indeed the missing arm of Laocoön, and it was added to the sculpture. The missing right arm was bent over the shoulder as Michelangelo supposed (this also means that the replicas of this sculpture from before 1960 are incorrect). In the 1980s all non-original additions to the sculpture were removed, and the sculpture became like we can see it today.

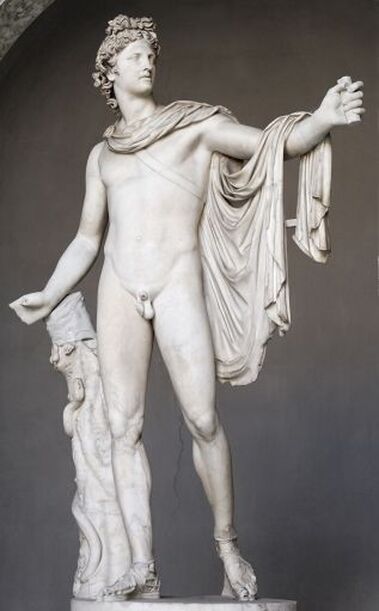

Where? The Octagonal Court of the Museo Pio Clementino in the Vatican Museums

When? Probably between 117 and 138 AD What do you see? A marble statue of 88 inches (2.24 meters) of a beardless, athletic Apollo. The surface of the statue is very smooth. Apollo’s face shows a neutral expression. He steps forward a bit with his right leg and throws back his cloak over his left shoulder to show his fully naked body. He looks to his left and has his left arm stretched out to support his cloak. Apollo has beautiful curly hair. His hair is tied on the top with a band and his curls hang down his neck. Around his torso, he is wearing a quiver to hold his arrows. He is also wearing sandals. On the left side (for the viewer), the statue is supported by a tree trunk, and you can see a snake carved on the left side of the tree. It is not entirely clear what mythological story is depicted in this statue, though it is suggested that Apollo originally was carrying a bow and arrow. This pose may represent Apollo who has just released an arrow with the bow that he was holding in his left hand. Some people suggest that this statue represents the moment that Apollo has just killed the serpent (which is a dragon) Python. The snake on the left, which may be a python, may serve as additional evidence to support this story. Backstory: This statue has been discovered in the 15th century and is also known as the Pythian Apollo. It was probably found around 1485 in Anzio, which is about 35 miles south of Rome. This statue is a Roman copy of an ancient Greek bronze statue. It is unknown who sculpted the current version of the statue. Leochares may have sculpted the original bronze statue in the 4th century BC. Originally, the right forearm and left hand of the Apollo Belvedere were missing, but they have been restored around 1532 by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (a pupil of Michelangelo). Near the end of the 15th century, the statue has been acquired by Giuliano della Rovere, a great art collector, who became later Pope Julius II. The statue has been named after the Belvedere Court in the Vatican Museums where the statue was placed in 1511. It has stayed there since then, except for a period of almost 20 years when Napoleon took it and displayed in Paris. Thanks to the efforts of, among others, Antonio Canova, the statue returned to its original location. The Octagonal Court: The Octagonal Court is currently part of the Vatican Museums. The court has been designated by Pope Julius II (1503-1513) to display antique classical statues. It is an open-air court containing several famous statues from antiquity. Its name is derived from the octagonal shape of the court and was given by Pope Clement XIV in 1772. Shortly after that, the court was incorporated in the Vatican Museums and opened to the public. The Apollo Belvedere and the statue of Laocoön and His Sons are the most famous statues in this court, and both have been there from the beginning.

Who is Apollo? Apollo is the god of, among others, archery, art, music, and poetry. He is the son of Zeus and Leto and the twin sister of Artemis. In Greek mythology, he is considered to be the most beautiful man that can be imagined. A bow and arrows are his most important attributes to represent his role as the god of archery. He received these attributes from Hephaestus, the blacksmith for the gods.

However, in this statue, there are no bow and arrows, though he is wearing a quiver that usually contains arrows. He probably held the bow in his left hand. You can still see a small part of the bow in his hand, but the rest of the bow was lost before the statue was discovered. Copies and inspiration: The Apollo Belvedere has for a long time been considered as the ideal depiction of male beauty. It has been copied many times and has served as an inspiration for many future artists. For example, artists such as Michelangelo and Dürer have used it as an inspiration for their sketches and sculptures. This statue also had a big influence on the Neoclassical sculptors, such as Antonio Canova. For example, his statue of Perseus with the Head of Medusa has been directly inspired by the Apollo Belvedere. The head of the Apollo Belvedere has also been used for the emblem of the Apollo 17 lunar landing mission in 1972, which has been the last moon landing mission to date.

Fun fact: Johann Winckelmann is a famous art historian, and in his book History of Ancient Art, he poetically describes ancient art. His book also contains a description of the Apollo Belvedere. He classified the Apollo Belvedere as “the highest ideal of art” among all classic works that have survived. He classifies this statue as a beauty that transcends the beauty that we can find in this world. He admits that his words can never describe the beauty of this sculpture and looking at the statue transfers his mind to an earthly paradise.

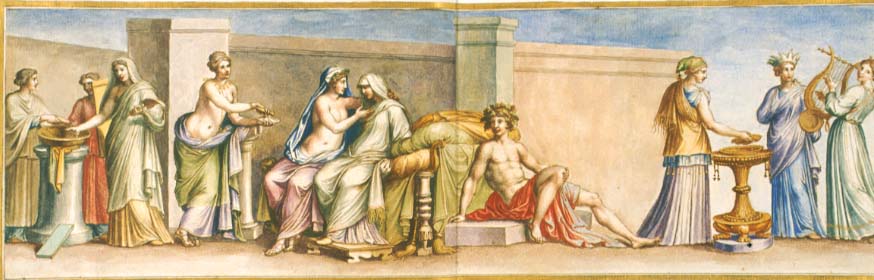

Where? Room of the Aldobrandini Wedding in the Vatican Museums

When? The first century B.C. What do you see? The painting is divided into three scenes taking place in three separate areas divided by walls.

Alternative interpretations: The meaning of this fresco is subject to a lot of debate and there is serious doubt on whether this is indeed a wedding scene as its title suggests. One alternative interpretation put forward by Frank Müller in 1994 is that the fresco shows a scene from Hippolytus Stephanephoros, a tragedy written by Euripides around 428 B.C. According to Müller's interpretation, the woman dressed in white is Phaedra, a princess from Crete. She was in love with Hippolytus, the man to the right of her. Phaedra is full of guilt as she is married to Theseus (who is the father of Hippolytus). Aphrodite comforts Phaedra. To the left of Aphrodite is her daughter Peitho. On the left is a tablet standing against a pillar containing a love declaration from Phaedra. The two people on the left perform magic spells to win over Hippolytus for Phaedra as Hippolytus is not interested in her yet. On the right is Artemis, who protects Hippolytus, surrounded by two of her nymphs. This interpretation is not without problems, but one argument in favor of it is that other frescos created around the same time often show mythological stories of tragic wives. Backstory: This fresco is from the first century B.C. It is part of a larger fresco, probably a frieze near the ceiling in a retiring room in an Ancient Roman house. The fresco was discovered around 1601 in the remains of an ancient house on the Esquiline Hill (one of the seven hills on which Rome is built). Cardinal Cinzio Passeri Aldobrandini (1551-1610) came in possession of this fresco, explaining the name of the fresco, and it stayed within his family until 1818. In that year, Pope Pius VII bought the fresco from the Aldobrandini family and in 1838 it was placed on display on its current spot in the Vatican Museums. Replicas: Before the 19th century, this was one of the few Ancient Roman frescos that were rediscovered. This fresco inspired many artists to copy it, including Poussin, Rubens, Van Dyck. In 1674, Pietro Santi Bartoli created a beautiful watercolor replica of the Aldobrandini Wedding. The fresco is also featured in Giovanni Paolo Panini’s painting Ancient Rome which is on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Louvre, and the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart.

Fun fact: The discussion about what this painting represents is still ongoing. The traditional interpretation that this fresco shows a wedding scene has been countered by various mythological interpretations. These interpretations look carefully at each attribute in the painting to understand who the different figures represent.

However, one simple argument against interpreting this fresco as a wedding is that none of the people looks even remotely happy. Especially the supposed wedding couple looks far from happy. While one may argue that the preparations for a wedding are stressful, that would still leave the question why someone would like to have a wedding scene with such serious and concerned faces on his or her wall. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us