|

Where? Gallery 243 of The Art Institute of Chicago

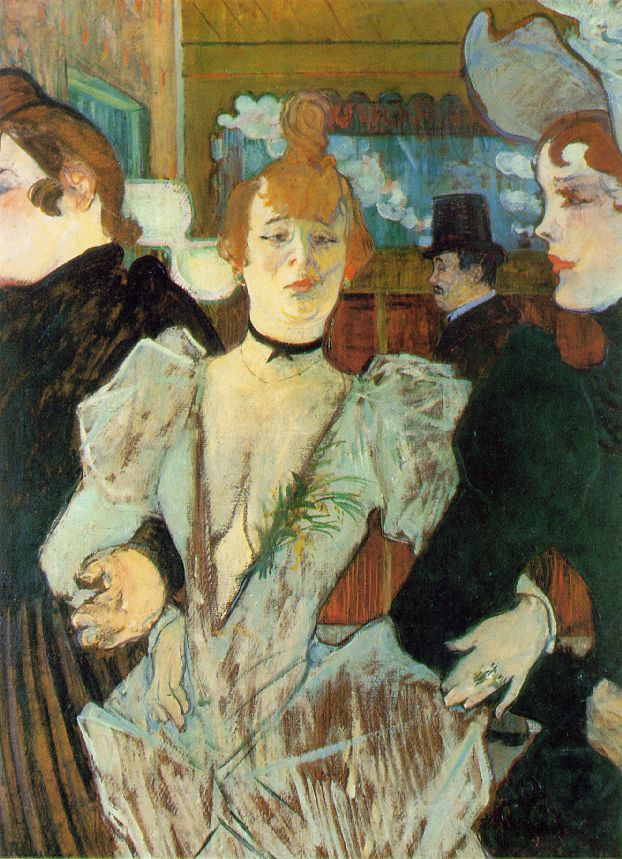

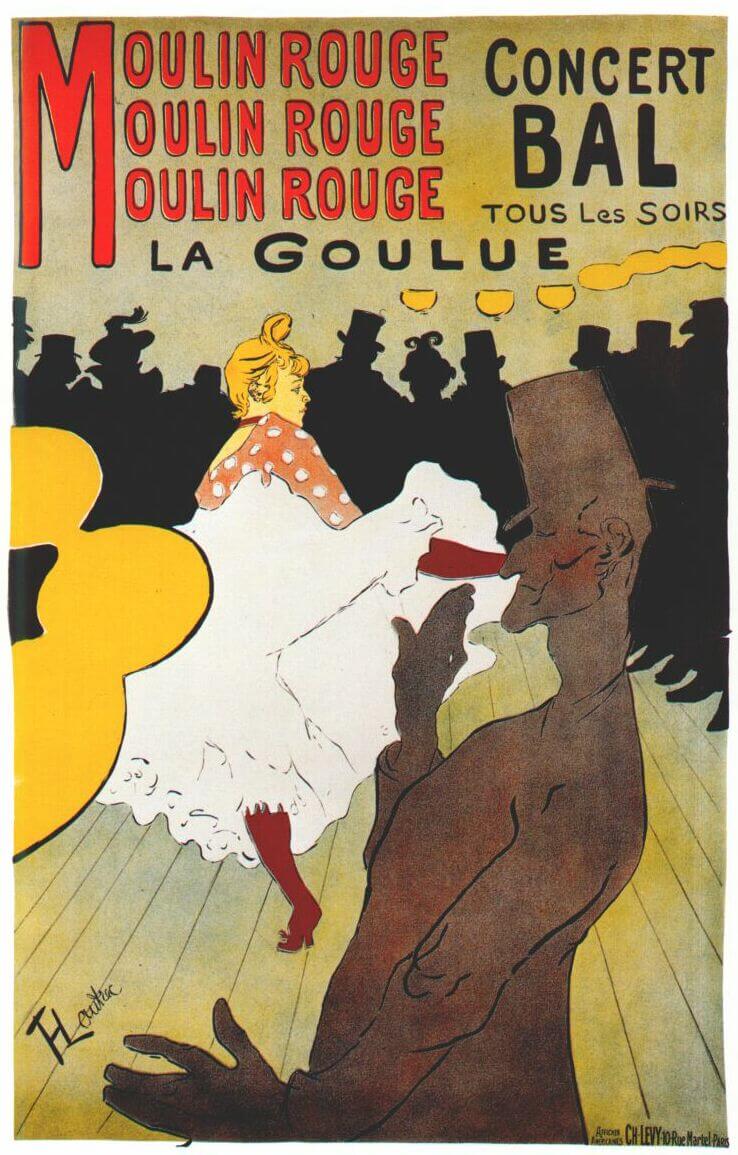

When? 1892-1895 What do you see? Behind a balustrade in one of the most popular nightclubs in Paris, three men and two women sit at a table, leaning into conversation. There are drinks on the table and each member of the party wears a fancy hat. The woman with orange hair is Jane Avril, a famous entertainer. Behind their table, one tall and one short man are passing by. In the right background, two women stand by a green mirror. The one fixing her hair is dancer La Goulue. Looking deeper into the room, there are many more guests sitting at tables with yellow lights hanging above them. Such a light may hang above the dancer May Milton in the left foreground. She stares at us with her bright teal skin, and her features have become grotesque and distorted under the harsh nightclub lights. Backstory: In the risky neighborhood of Montmartre, Paris, nightlife flourished through the end of the 19th century. People of various classes came to the nightclubs and dance halls in Montmartre to experience a social life unlike any other. In its heyday, the area was actually quite dangerous, but it has since been romanticized and sensationalized so that images and music associated with it evoke great nostalgia. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec frequently visited the Moulin Rouge, a nightclub in the neighborhood. As such, he was very familiar with the other regulars. In At the Moulin Rouge, he was able to capture these characters on canvas and portray the true grunge of the Paris nightlife culture. Using bright colors and thick brush strokes, Toulouse-Lautrec paints in an Avant-Garde style, apt for his subject matter. What is the Moulin Rouge? Established in 1889, the Moulin Rouge was a cabaret and nightclub located in the Montmartre district of Paris. Featuring live performances from the stars of Paris, drinks, and room for socialization, the Moulin Rouge was a truly modern space. The iconic can-can dance was first performed at the Moulin Rouge, and, at the time, it was considered a very improper dance. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec created several advertising posters for the Moulin Rouge, as well as several paintings of the Moulin Rouge. Among those paintings are At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and La Goulue at the Moulin Rouge in the Museum of Modern Art.

Who is Toulouse-Lautrec? Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec was born in Albi, France in 1864 to a wealthy family. As his mother and father were first cousins, Toulouse-Lautrec suffered from congenital health issues that affected his bones and growth. Due to these health issues, he became slightly isolated from society and spent his time making art. Painting in the Post-Impressionist style and printmaking in the Art Nouveau style, Toulouse-Lautrec captured the Bohemian lifestyle of 19th-century Paris. This was the lifestyle Toulouse-Lautrec immersed himself in Montmartre’s Moulin Rouge. He created a series of posters advertising the cabaret and displayed his artworks there.

Fun fact: The two men walking behind the table in the center of the painting are actually Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec himself and his cousin, Dr. Gabriel Tapié de Céleyran.

0 Comments

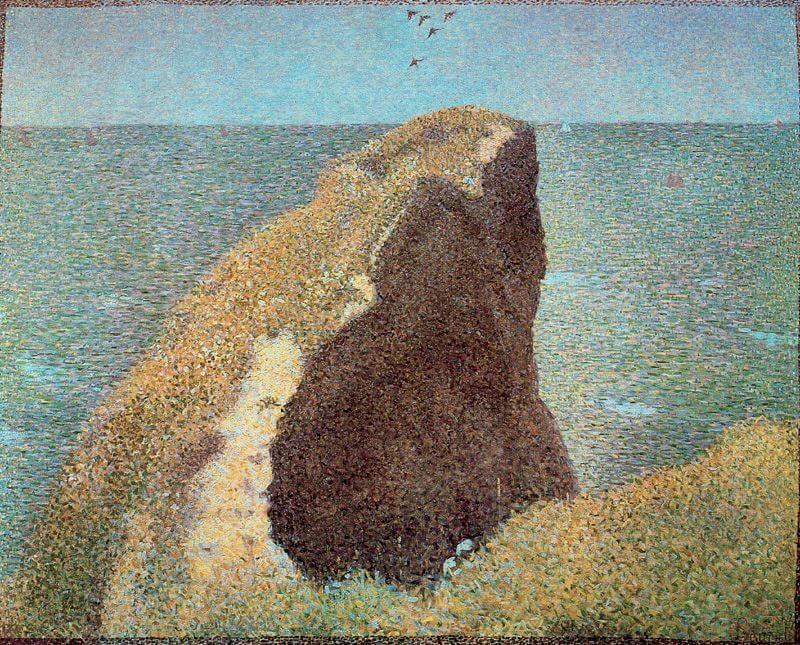

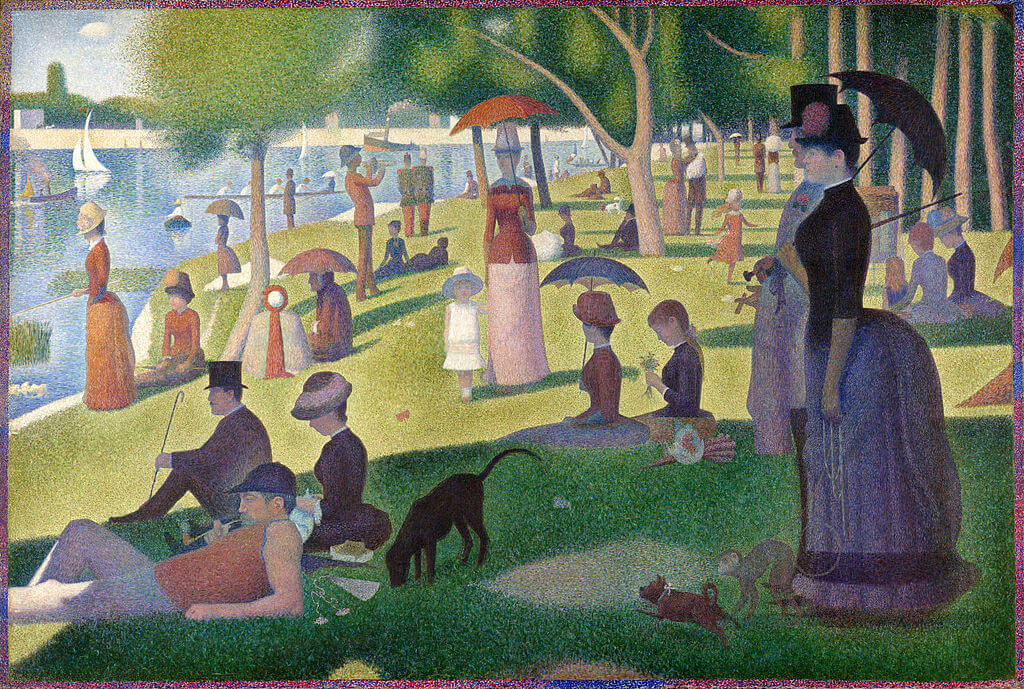

Where? Floor 5, Gallery 1 of the Museum of Modern Art When? 1885 What do you see? The arrival of the evening in Grandcamp on the Northwest coast of France. The sky is a beautiful combination of white, silver, and gray. On the right is the Atlantic Ocean with a single sailboat. Seurat painted the sea and the sky using small horizontal brush strokes to indicate the direction in which the sea and sky are moving. In contrast, he painted the using dots of paint, which you can see very clearly when standing close to the painting. Some of the objects are very unclear from up-close. For example, look at the sailboat on the sea. However, from a distance, all the dots and small brush strokes come together, and the different elements of the painting become very clear. From a distance, we have no problem identifying a sailboat in this painting. Backstory: In 1885, Seurat spent his Summer in Grandcamp, Normandy, on the French coast. That Summer he painted several seascapes. Two examples of other works he created in Grandcamp that Summer are Ruins at Grandcamp in the Musée d’Orsay and Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp in Tate Modern.

Beyond Impressionism: Impressionism developed under the lead of Édouard Manet in the 1860s, and by the 1880s, Impressionism gained quite some popularity. However, among the next generation of artists, there were several innovative painters that went beyond Impressionism, usually labeled under the umbrella term Post-Impressionism.

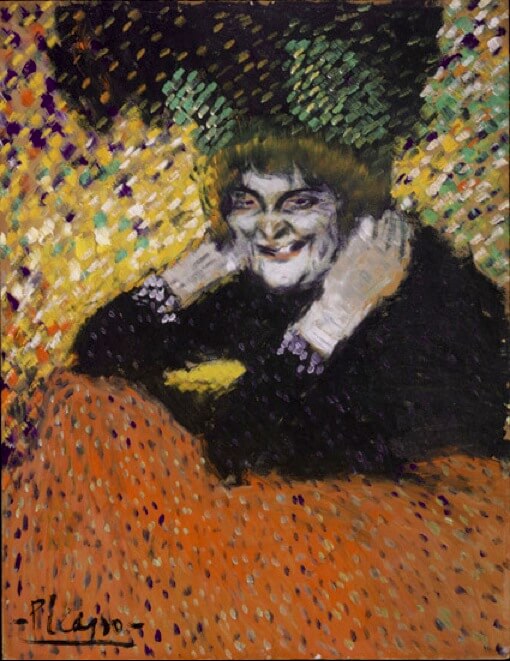

What is Neo-Impressionism? An art movement created by Georges Seurat in 1884. Neo-Impressionism involved a scientific interpretation of colors and lines. The paint was applied in pure, unmixed dots and blocks of colors, creating a strong sense of organization. Scientific principles guided the choice of contrasting colors such that the colors interacted optically (instead of mixing the colors in the painting). This creates a special effect for the viewer. Looking at the paintings from nearby, one sees a lot of dots of pure colors. However, from a distance, these colors interact beautifully, and the painting becomes a unified whole of almost unmatched clarity. One great example of this style from 1892 is Femmes au Puits by Paul Signac in the Musée d’Orsay. A later example from 1902 is Old Woman by Pablo Picasso in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Who is Seurat? Georges-Pierre Seurat (1859-1891) was born and raised in Paris. He only became 31 years old and died in the midst of his career from an unknown disease. He was a Post-Impressionist painter. He can be classified even more accurately as a Neo-Impressionist painter.

Seurat received a classical art training at the traditional École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. While his painting style was far from traditional, his ideas benefited greatly from his education. He used a scientific approach to painting, whereby different colors can create different emotions and combining specific colors can create harmony in a painting. Seurat decided not to combine colors in a painting, but instead to apply the colors separately, using small dots, and let the viewer combine the colors in his/her mind. The best-known painting by Seurat is A Sunday at La Grande Jatte – 1884 in the Art Institute of Chicago.

Fun fact: Seurat completed this painting in 1885. Only three years later, he added the border of the painting. He did this to increase the brightness of the colors. This addition perfectly fits with the ideas and style of painting that Seurat used. The colors are carefully chosen to complement each other, and the contrasting colors in the border make the painting itself, and especially the sea and the sky stand out more.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster

Where: Gallery 248 at the Art Institute of Chicago

When: c. 1893 Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 65 cm x 80 cm (25.6 x 31.5 in.). What do you see? At first glance, the tabletop, the basket of apples, wine bottle, plate of biscuits, apples tumbling across the tablecloth and surfaces, may appear to be a straightforward still-life painting but a longer look will show that it is much more than that. Cézanne had been rejected by the public for so many years that he had freed himself to see and paint to his own dictates. His still-life depictions are complex compositions that continue to provide the harmony and unity of his subjects that was so important to his philosophy of art, but he was experimenting at the same time. At first glance, we see a pleasing colorful painting that invites us in for a longer look. Cézanne, while showing himself and his viewers a kaleidoscope of perspectives, broke the rules of art with impunity. This painting provides a perfect example of what he did in order to portray our human visual perceptions that operate on so many levels in order to interpret our surrounding environment and what we see. Impossible Perspective? The longer look reveals a table that is impossible. The supports on the left and right sides are not the same height. The tabletop is not even on both sides and also not the same color. An extra tabletop can be seen on the right side. The back of the table on the left and right sides are also not on the same levels. We are looking at a variety of differing viewpoints. The table is tilted towards the viewer and on the left, yet another level supports the apple basket in a position that seems impossible as well. Does the wall support the basket? The green wine bottle is not symmetrical and leans slightly towards the left. Does it also support the basket? Even the biscuits on the plate provide differing views; we see both a side and top view at the same time. Cézanne has manipulated the biscuits by angling and elevating the two upper biscuits so we see two whole tops. There is a grey gap on the right side that creates a tilt in the edge of the upper back part of the table. It gives the impression that the right back part of the table is holding some of the fruit in place to keep it from rolling off into space. A pear at the edge of the gap also seems to act as a stopper. The folds of the tablecloth contain some of the loose fruits with a power that is stronger than simple cotton. Cézanne was known to impregnate his cloths with plaster of Paris to make them firm. Perhaps this is an example of that technique. A long grey fold that starts just right of the center of the painting, guides the eye into the scene and it provides a suggestion of depth, yet the cloth still seems to be about to fall from the table because of the illusion of a forward tilt. The feeling is augmented by the lack of a clear table edge on the left side. The wine bottle provides a vertical center that is surrounded by a variety of horizontal planes that do not interfere with the perception of the whole. Cézanne made clever use of grey tones on the wall, on the basket support, the plate of biscuits, the grey gap in the table on the right and the grey on the table in the front, plus the grey highlights on the cloth to unite all elements. Back Story: Paul Cézanne was 54 years old in 1893 and would only live another 13 years. His exploration of techniques, styles and mediums was extensive by this time and covered his full range of compositions and subjects. His progress over time is clearly visible whether he was painting a portrait, a landscape or a still life. His concerns centered on the artist’s interpretation and portrayal of a subject. His viewers should perceive all sides and the inside-out in their perception of harmony and unity in his works. He wanted his viewers to see and feel the wind in a landscape, find the personality in a portrait, and understand all sides of the objects in a still-life as he presented it. How we perceive visual stimuli was a major concern in all he did. Influence of Chardin: In his early years, Cézanne visited the Louvre and became familiar with the work of Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin. Chardin had been considered one of the most revolutionary artists of 18th century France, in particular having raised the lowly art form of still life painting to a level of popularity not known before in France. His desire to paint reality came from the Age of the Enlightenment. “Sensations of the mind” were being questioned. There was the belief that painters could “manipulate colors and shapes to induce particular responses in the viewer”. The American art historian Theodore Reff suggested the influence that Chardin may have had on Cézanne: “It would be hard to imagine the emergence of still life as a major category of modern art without the example of Cézanne from about 1875 on and equally hard to imagine his achievement without the revival of Chardin some thirty years earlier … Chardin did not use trompe-l’oeil to deceive by an optical illusion … his aim was to re-create the living, moving character of the vision of reality.”

Chardin tended to place his objects in a line, interacting with each other but separate. A slice of brioche and a bite of the cherries from the table is inviting. He always led viewers into his still-life by using a long object as above or a knife in order to emphasize the depth of the table. Cézanne used the same technique as both artists attempted to imitate reality on canvas. But Cézanne took the genre into another level of perception as described above and seen below.

The differences in the compositions of these two artists may be subtle but Chardin’s horizontal plane is absolute. The knife and the rumpled cloth lead the eye into each painting but Cézanne plays with our perceptions of reality as he tilts the plate of cherries to give us the best possible view. He was not afraid of deviating from the linear perspective that artists and collectors were so familiar with. Chardin’s stacked peaches provide the vertical element just as the green jar does in Cézanne’s work. Chardin’s perfect peaches even provide the fuzz, where Cézanne’s peaches have imperfections. His paint spills out of the outline, layers of green beneath are visible but when looked at from a distance, they remain realistic and appealing.

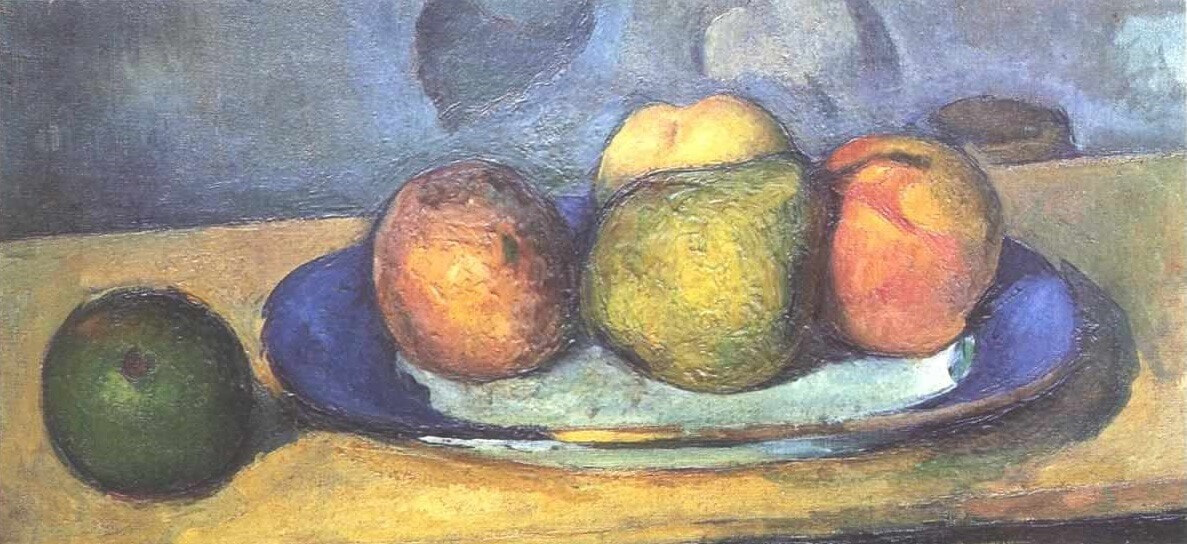

Still-Life Paintings by Cézanne: Cézanne said he wanted to “shock Paris with an apple.” Never before had everyday objects been presented in quite the manner in which he painted. He was always concerned with “color value, color schemes and creating form with color. His hatching style of brushstrokes and his outlining gave his objects their own subjective space” (Duchting, 2003). His Fruits on a Blue Plate seen above, reveals each technique. Tonally blue, simple color scheme of blues and yellow (blue and yellow make green), the distinctive brush strokes on the fruit, layered to give volume and form, and the final outlining to separate each object, yet he maintains their intimate relationships. There is a blue haze over the whole painting uniting the parts.

Still Life with a Ginger Jar and Eggplants, painted between 1893 and 1894, shows how the blue drapery with its patterns and folds gives volume and texture to the painting. There is a slight suggestion of a table on the left-hand side near the bottom but without that, the materials and objects look almost suspended in air. Cézanne integrates his geometric shapes of circles, triangles and domes to compose interesting pattern after pattern. The relationship between the ginger jar and the green objects catches the eye. The brownish pear behind the plate of fruit transitions the colors of the rum bottle and the eggplants so they are included in the grouping in a natural manner. The pear with its yellowish highlights, helps to keep the relationship with the plate of fruit and the lemon on its own, as integral to the work. Cézanne has tilted the plate to provide a good view of all the fruit but again disregards the rules of linear perspective as these fruits should be falling onto the floor. He keeps us off balance by painting an impossible table in the background. Legs may be intimated but we cannot see them, and the table should be falling too.

Cézanne worked slowly and each brush stroke was thought out a thousand times. To Gasquet (his young student and confidante), he said: “You have to get hold of these fellows … these glasses, these plates, they talk to each other, they’re constantly telling confidences.” The intensity and the love that he put into these objects is remarkable. Cézanne’s motifs may be still or appear quiet but he creates tension and suspense that draws an emotional response from his viewers. Again, to Gasquet, he said: “The eye must grasp, bring things together. The brain will give it all shape.”

Early Still Life Paintings: These two earlier still-life paintings from the 1860s are much more classical in composition and style. Like Chardin, his objects are in a relatively straight line. A knife in the first work guides the eye into the painting. It’s function to cut the bread is plain. The cloth is definitely resting on a table as we see the outline of it, unlike his later paintings. In the second painting we see a difference. His brush strokes slash across the pears, thick paint bursting the edges in places. It looks hurried and tense as can be seen in his early landscapes and narrative paintings. Nothing quite like this had been seen before in his contemporary world. He would not find success until much later in his life when his still-life paintings were finally admired by the general public.

Cézanne painted the same object again and again and, as one looks through his work, they become recognizable quickly. By 1877, his compositions are still following the rules. Plate with Fruits and Sponge Fingers (1877) shows the straight line of objects and their relationships with each other in a realistic manner. The biscuits here are straightforward and meet our visual expectations, unlike the initial painting above from 1893. In the following years, Cézanne worked diligently and constantly to present all the dimensions of our sensations on multiple levels so that he and we could see his objects in a new way. This was true of all his subjects, whether in a landscape, a portrait, or a still life.

Atmosphere: According to Hajo Duchting’s 2003 book about Cézanne, the artist also wanted to: “reproduce the atmosphere of things. The starting point and central motif of his still-lifes are fruits.” To Gasquet, again he described his thoughts. “I decided against flowers. They wither on the instant. Fruits are more loyal. It is as if they were begging forgiveness for losing their color. The idea exuded from them together with their fragrance. They come to you laden with scents, tell you of the fields they have left behind, the rain that nourished them, the dawns they have seen. When you translate the skin of a beautiful peach in opulent strokes, or the melancholy of an old apple, you sense their mutual reflections, the same mild shadows of relinquishment, the same loving sun, the same recollections of dew…".

Still Life With Basket of Fruit (1888-1890) shows various everyday objects. The ginger jar, a cream and sugar set, and the warm colors and tone of this painting are immediately comforting to look at. The chairs, the tables, the paintings on the wall are homely and inviting. Knowing how he felt about the fruit that he painted offers more sensation. Imagine the smells, the feel of the fruit and the desire to be in that room. Still, he played with the balance. The basket is too large for the table. The handle is not where we would expect to see it. The ginger jar is tipped forward, the tabletops and legs are not matched. The cream and sugar lean to the left and the creamer handle like the basket handle is not quite “right”. A large pear on the left is extraordinary and seems to be a weight to hold the table down. He painted in yellow and blue tones, creating a canvas full of relationships that are on different planes and levels. It is sensual: a basket of fresh fruit from the orchards, with the promise of a delicious dish of fruit with cream and sugar soon to come. The distorted whole enhances the pleasure of the painting.

Cézanne’s Legacy: Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin have become known as the Post-Impressionists, the artists who transitioned from the Impressionist movement into the Modern Art period. Instead of portraying purely visual stimuli, Cézanne, in particular, was attempting to put his mind and his perceptions on the canvas and it was Paul Cézanne who Pablo Picasso singled out when he said of him, “he is the father of us all”.

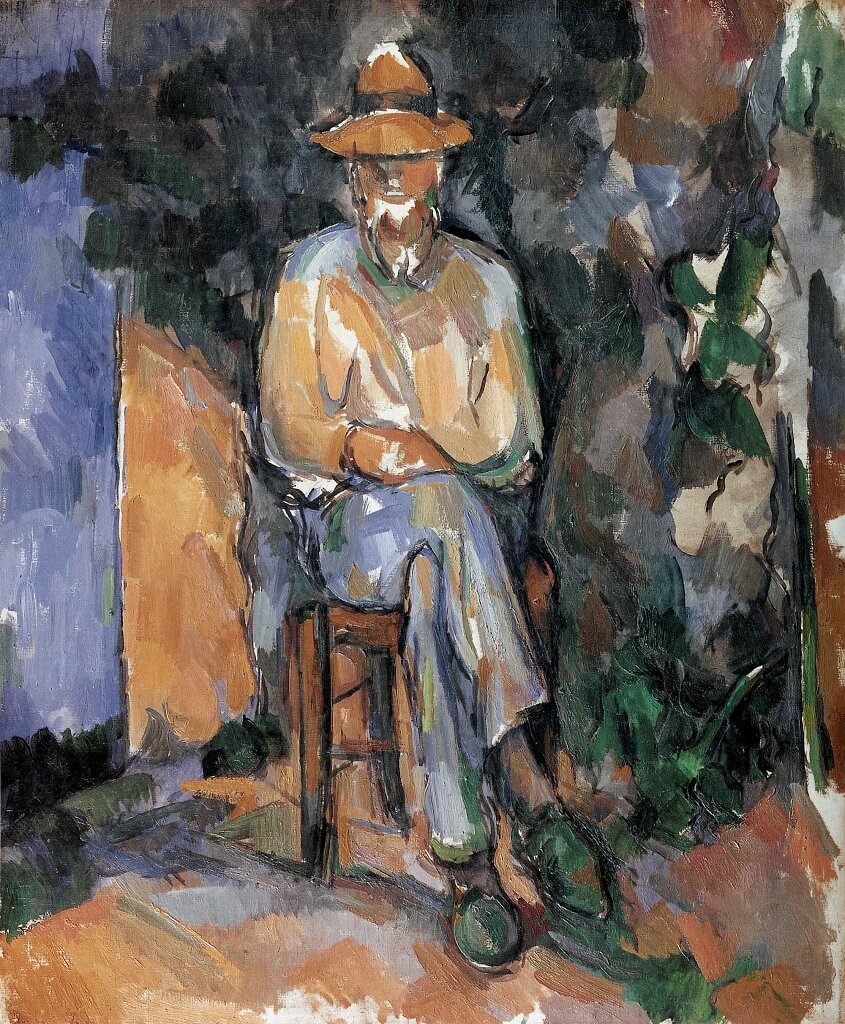

While Cézanne painted his colorful still-lifes, he continued to paint portraits and landscapes creating new views, different perspectives, and new ideas in all genres. He did say of himself, “I am the primitive of a new art”. He knew what he was doing was different. Portraits: Cézanne had hired Vallier to look after his garden in the Chemin des Lauves in 1902. He explained himself: “In today’s reality, everything is changing. But not for me. I am living in the town where I spent my childhood, under the eyes of people my own age, in whom I see my own past. I love above all things the way people look when they have grown old without violating tradition by embracing the laws of the present. I hate the effects those laws have.” His portraits are still, asking the viewer to stop and look at this man. In both paintings the man is at peace with himself, with who he is, with what he has done. The earth tones, the slashes of green, the deep dark of the foliage behind him and the wonderful straw hat all suggest peace with nature as well. Lurking in the back is the modern town as a reminder of the changes coming to the country. Cézanne’s colors flow, each brushstroke dependent on the next to provide the unity and harmony so spoken about in regard to his works. Each patch of paint reflects the one next to it as he builds his person in his environment. The Gardener Vallier (1906) seated on the chair is a looser composition, lighter and softer in tone. The painting has the same aura about it as its companion. The shapes formed by the color push towards the abstraction that followed. A frontal view with a slight turn to the right, allows us to see more of his body from differing angles. We can see these techniques in most of his works as he developed them over his lifetime.

Landscapes: Below are two landscape paintings by Paul Cézanne. In Gardanne (c. 1885), the building blocks are apparent and the Cubist beginnings are obvious. In Mont Sainte Victoire (1904), his style has developed much more. Cézanne was obsessed with Mont Sainte Victoire as he attempted to show every side and even the insides of this mountain. He painted it all his life and the painting below begins to take us into the world of abstraction. Each element in the painting is broken into pieces of itself but Cézanne has made certain they are still distinct.

Cézanne opened the door of possibilities for the Modern era artists with his unique use of colors and tones in his paints, the geometric shapes that were his building blocks and his compositions that changed the style of future art works. He perceived the world in a way not seen before and was brave enough to continue against all criticism and personal vitriol. Finally, he was at peace with his world and his work. He would be shocked now, to see the importance assigned to him.

Fun Fact: Recently, the Chief Conservator at the Cincinnati Museum of Art, Serena Surry, was examining, Still Life with Bread and Eggs (1865), as seen above. She became suspicious of what might be underneath and following x-rays, they found a “well defined portrait”. The staff are undertaking further investigation of the new-found work to find evidence as to whether it is a self-portrait of Cézanne or another individual.

Written by Carol Morse

References:

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

Where? The Courtauld Institute of Art in London

When? 1896 Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 64.0 x 81.3 cm. What do you see? A view of Lake Annecy and the Chateau de Duingt, situated in the French Alps, not far from the town of Annecy. The medieval fortress has been there since the 11th century. The view is from the opposite shore over the lake toward the castle. A large tree provides a frame on the left. The tree trunk disappears at the top edge, and the branches and boughs of the tree overhang the upper edge of the painting, their diagonal brushstrokes complimenting the background mountains and framing the view. The castle is situated at the center, with the lake in front and the mountains stretching into the distance behind the partially hidden buildings. Diagonal brushstrokes going in opposing directions create height and depth in the mountains. Highlights of rust, ochre, blues, and greens take the viewer deeper into the hills and valleys. The emerald/blue water is calming, with elongated reflections created with the edge of a palette knife. The light source comes from the left of the artwork and focuses attention on the reflections, tree trunk, and buildings. The contrast of the dark on the opposite side of the highlighting accentuates the importance of the objects in the painting. It is a peaceful scene, yet the composition and the colorings are somewhat startling at first glance. However, it is also a stirring work that asks the viewer to look harder.

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

Where? Barnes Foundation, Room 2, West Wall.

When? c. 1885 Medium and size? Oil on canvas, 65.0 x 100.3 cm. What do you see? A horizontal view of the city of Gardanne in Southern France. The panoramic view is controlled by the use of blue/gray tones to collect and join each building block of the painting. There are squares and rectangles that build the scene, creating the illusion of distance and leading the eye upward to the highest point where the important bell tower has been positioned in the center of the work. The trees and greenery form their own shapes that give more cohesiveness to the buildings. The outline strokes and the shadows delineate the red roofs and gently lead the eye up the hill. On the right-hand side, just above the top of the hill, are two towers that may be from factories beyond. There is an architectural feel to the painting, but the warmth of the colors dispels any coldness. The scene appears to lean slightly toward the left, which may add further interest to the whole.

Where? Floor 5, Gallery 1 of the Museum of Modern Art

When? June 1889 What do you see? This painting is an imaginative version of a starry night in Saint-Rémy in France where Van Gogh was staying at that time. The various elements in this painting are certainly inspired by what Van Gogh observed in reality, but he created his own ideal version of the starry night. In the painting, we can observe some trees, a village, and mountains under a night sky full of stars (or more precisely a collection of 12 celestial bodies). In the foreground, you can observe a big wavy cypress tree. The cypress is an element that comes back in multiple Van Gogh paintings, such as the Wheat Field with Cypresses in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the top right is a crescent moon. The brightest celestial body in the painting, just to the right of the cypress tree, is the planet Venus. The celestial bodies light up the sky (indicated by the use of white paint in the night sky). The church tower in the middle foreground is probably the Saint-Martin church in Saint-Rémy. Van Gogh, however, did not include the dome of the church in this painting. In the village surrounding the church, several houses still have their lights on. On the right side of the painting, between the village and the mountains, you can see a forest. The curvy lines used for the cypress tree and the clouds in the sky create a sense of movement in this painting. Notice also the clear contrast between the turbulent sky and the quiet life on earth. The cypress in the form of a big fire is the only element that connects the earth and sky with each other.

Backstory: The painting is created between June 16 and 18, 1889 when Van Gogh was staying in the hospital of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole at Saint-Rémy. In a letter to his brother Theo, he wrote: “This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big.” He mixed this view both with some other elements that he observed in the area of Saint-Rémy and his imagination to create this painting.

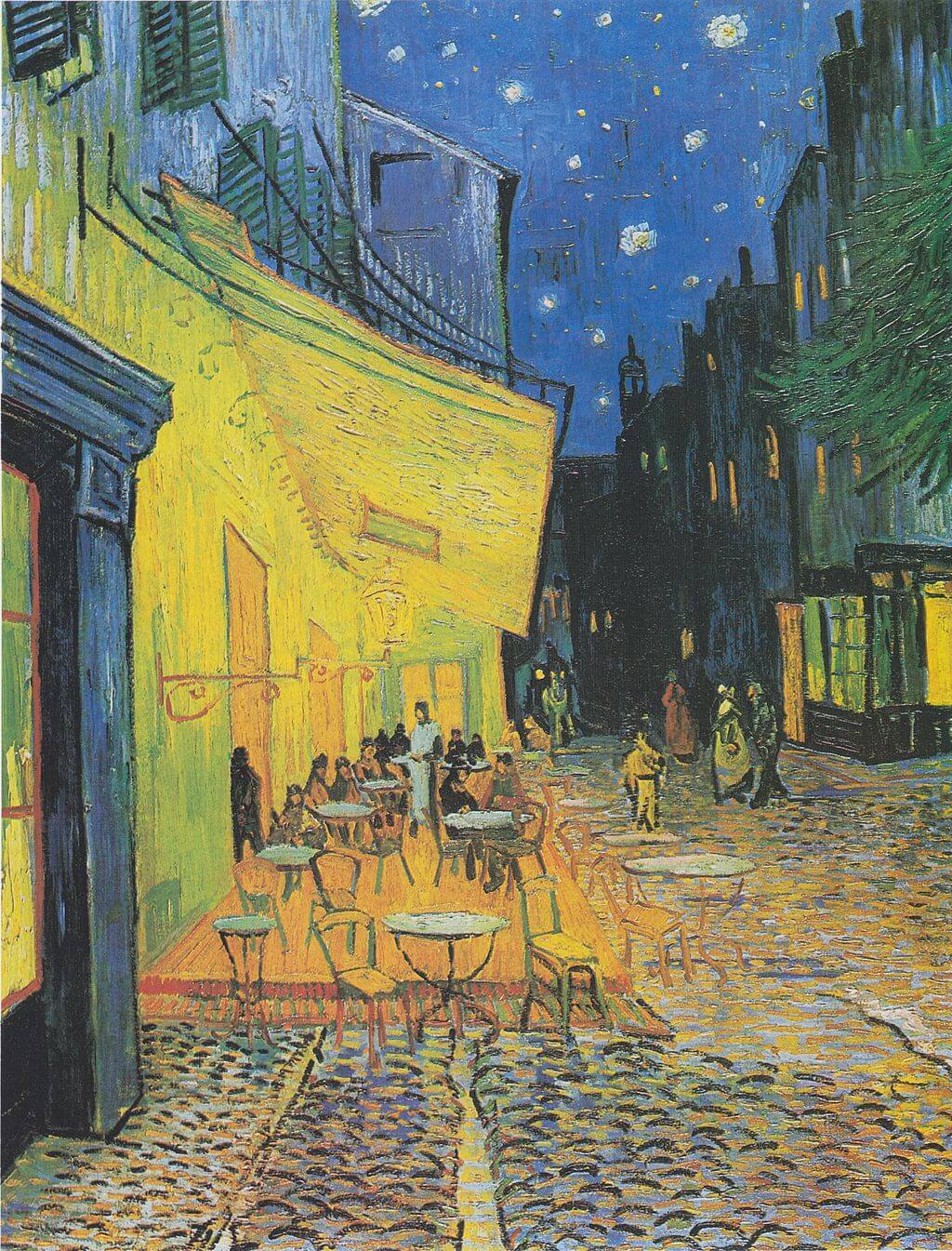

Van Gogh used thick broad strokes of oil paint to create this painting and it was probably created in a single day (even though the idea for this painting was already occupying his mind for over a year). If you look carefully, you can still see some pieces of the canvas in between the broad strokes of paint. Symbolism: There is some debate on whether this painting should be interpreted symbolically. One symbolic explanation for this painting centers around the cypress which connects the earth to the sky in this painting. The cypress tree is associated with cemeteries and death. In this painting, it could be the connection between life (which happens on earth) and death (which is when you go to the stars according to Van Gogh). Van Gogh wrote in one of his letters “We take death to go to a star.” Van Gogh, who would eventually commit suicide, was interested in death and he expressed some ideas that one would go to the stars after death. Other versions of the Starry Night? Van Gogh was already interested in the idea of painting a starry night in 1888 as expressed in several letters to his friends and brother. Indeed, in 1888 he painted two versions of a starry night. The first version is Café Terrace at Night which is in the Kröller-Müller Museum in The Netherlands. The second version is Starry Night over the Rhône which is in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. However, these two paintings did not fulfill his idea of a perfect starry night. Instead of a starry night above a town, he was more interested in a starry night above a landscape and a more imaginative version of the night sky.

Who is Van Gogh? Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) was born in Zundert in The Netherlands. At the end of his life, he created many paintings that fall under the Post-Impressionist style. Van Gogh has produced a large number of paintings during his life and most of them have been painted in the last two years of his life.

Vincent van Gogh wrote many letters during his life -- many of which to his brother Theo -- which have been saved. In these letters, he explained his ideas about painting and they form a valuable source to interpret his works. The work of Van Gogh was not really appreciated during his life, but his work has become famous after his suicide in 1890. Fun fact: While this is nowadays considered to be one of the best paintings by Vincent van Gogh, he did not seem very proud of this painting. When he wrote a letter to his brother Theo after he left Saint-Rémy, he did not mention this painting as a good one. In fact, he listed several paintings, including the Wheatfield with Cypresses, as “a little good.” About the other paintings from that period, including this painting, he writes “the rest says nothing to me.” His brother Theo seemed to agree that The Starry Night is not his best work. He was worried about the more imaginary nature of this work compared to the somewhat more realistic paintings he created before. He advised Vincent to stick to still lifes and flowers as that would have more therapeutic value for the mentally troubled Vincent.

Where? Gallery 825 of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

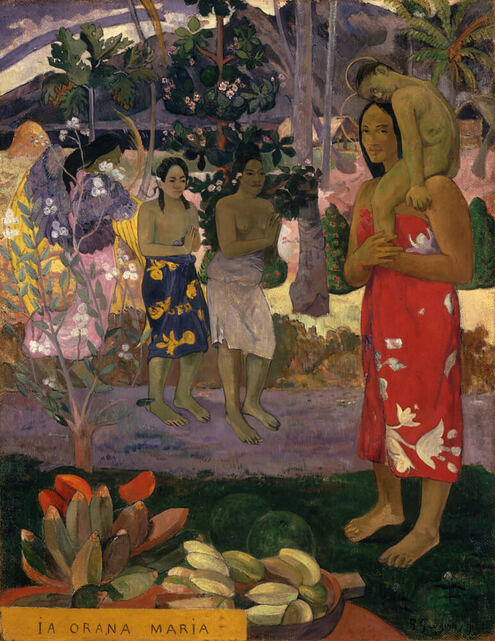

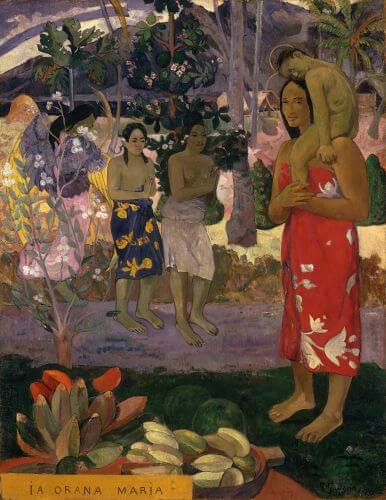

When? 1891 What do you see? This painting contains five people. On the right is Mary with her naked child Jesus sitting in an odd pose on her shoulder. Both have a halo around their head and are looking at the viewer. Mary is wearing a red pareo (which is a dress that is wrapped around the middle or higher and is typical for people in Tahiti and the Cook Islands) wrapped around her with a hibiscus flower motif on it. On the left, you can see a female angel (probably representing the Archangel Gabriel) dressed in pink and with blue and yellow wings. The angel is partly hidden behind a flowering tree. The angel points out the presence of Mary and Jesus to the two Tahitian women on the purple path. These two women are dressed in a pareo from the waist down, and they fold their hands in devotion. In the foreground is a collection of fruit laying on a fata, which is a wooden altar that Polynesians use to make offers to their gods. These fruits may be an analogy to the gifts that the three Magi brought to Jesus after his birth. The fruit includes red and yellow Tahitian bananas (some of which are in a wooden bowl) and the green breadfruit in the center. In the background, you can see the dark mountains, a lake, palm trees, and flowering bushes. There is a boathouse on the right side of the lake.

What is Hail Mary? Also known as the Angelic Salutation or Ave Maria, Hail Mary is a prayer in the Catholic Church. The full text of this prayer is:

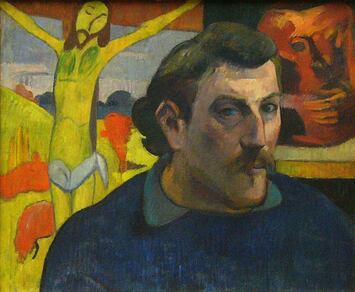

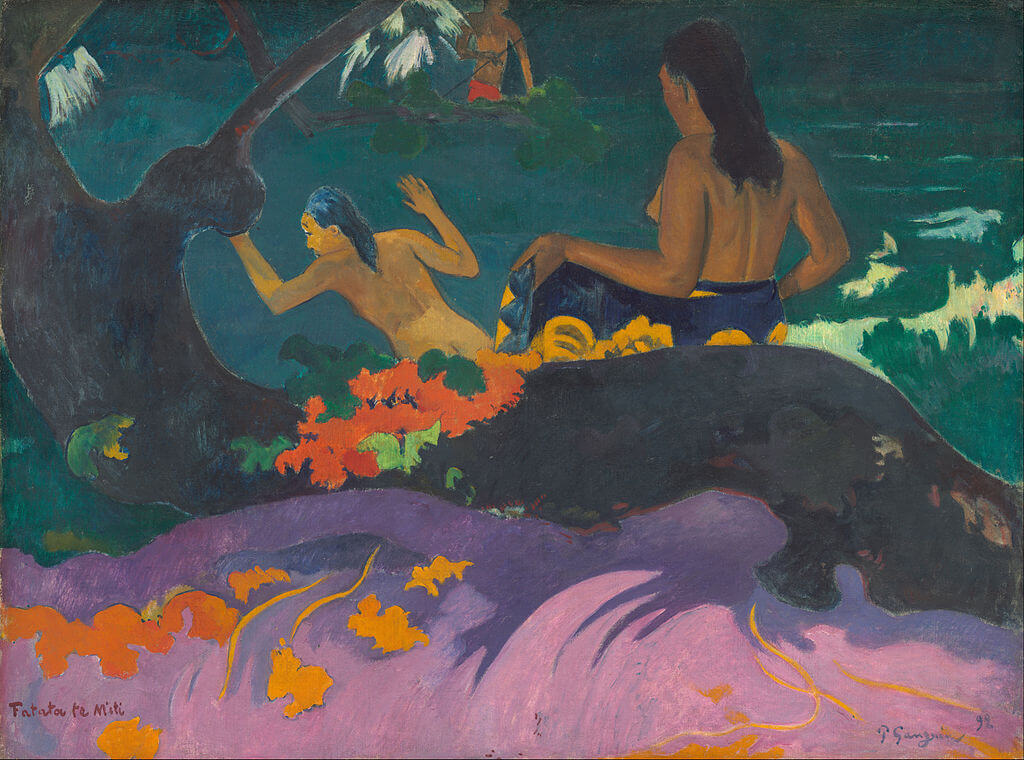

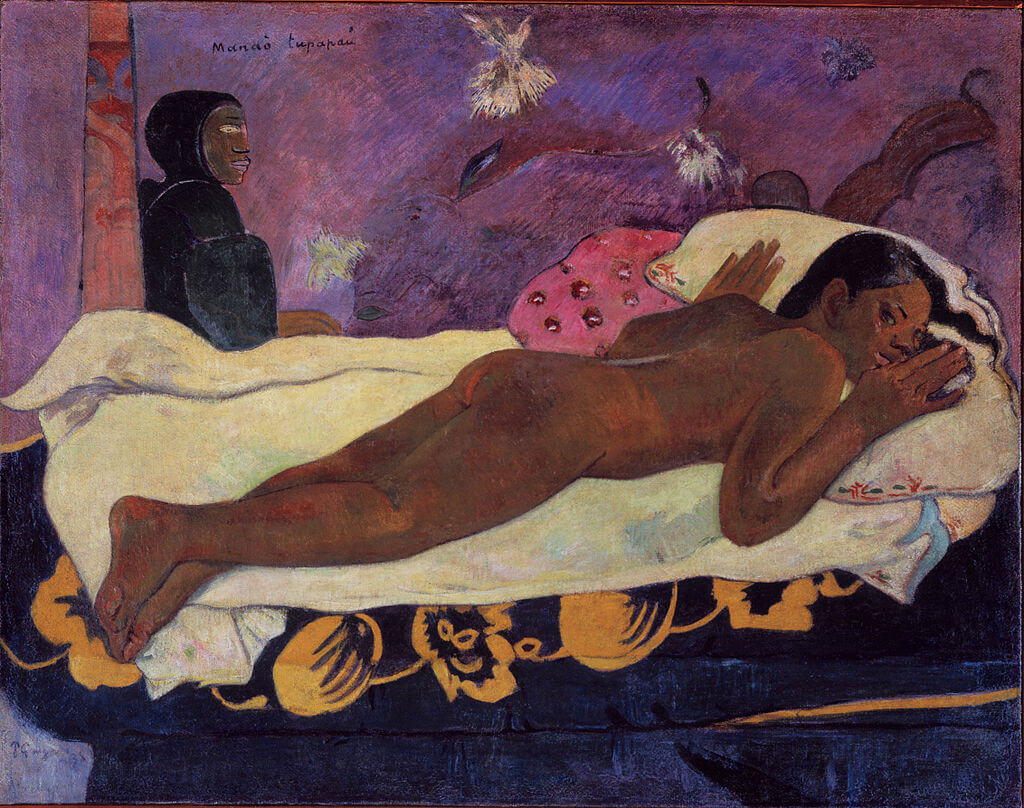

“Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou amongst women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now, and in the hour of our death. Amen.” This prayer is the most popular prayer aimed at Mary and asks for her help in intervening between the person praying and God. Who is Gauguin? Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) is a Post-Impressionist artist who is known for his experimental use of colors. Vincent van Gogh and Edgar Degas were important for Gauguin in developing his unique style. In 1891, Gauguin moved to Tahiti to start a new life. His idea was to set up a community of painters, called l’atelier des tropiques in an area that was far away from home and did not suffer from the materialism that was present in France. The main idea behind this initiative was to stimulate the role of spirituality in their artworks and to expose themselves to different cultures and religions. In the end, no other painters joined him, and he left alone to Tahiti. However, this did not have a negative effect on the quality of Gauguin’s work, and he produced some of his best works during this period, including By the Sea (Fatata te Miti) in the National Gallery of Art and Spirit of the Dead Watching (Manao Tupapau) in the Albright–Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo. Most of Gauguin’s paintings are based on his imagination, and he expressed in a letter to his wife that he believed that his artistic center was in his mind and did not need to be inspired by other painters.

Fun fact: Gauguin did not have any models from Tahiti in front of him to paint this picture, but rather painted this based on his imagination and some other stimuli that he brought to Tahiti. For example, as Tahitians were not walking around half-naked, the two women in the middle are modeled after the figures of dancers on a bas-relief of the Javanese Borobudur temple of which he had brought a picture. Also, the pose of Jesus on top of Mary’s shoulder was based on a postcard that Gauguin bought during his trip to Tahiti. Moreover, Gauguin was one of the first artists to depict Mary and Jesus with a colored skin, something that was not allowed yet by the Catholic Church.

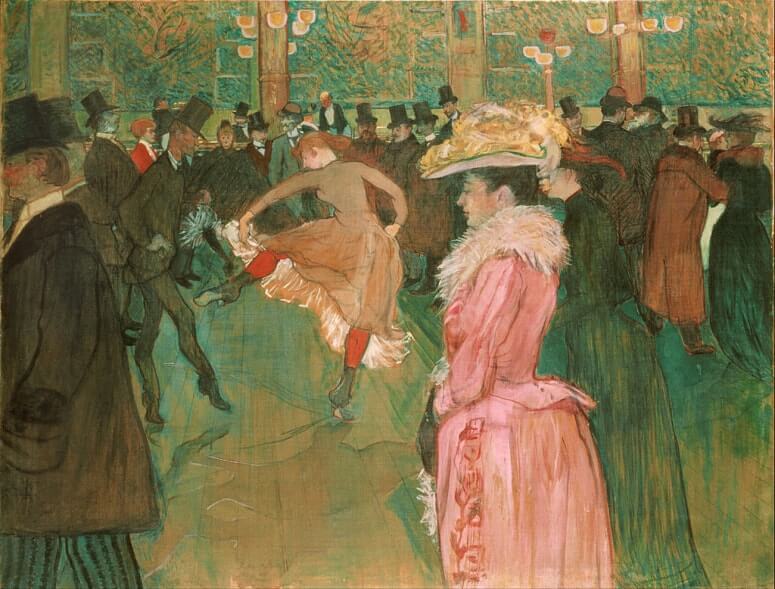

Where? Gallery 165 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

When? 1890 What do you see? The couple in the middle is dancing the can-can in the Moulin Rouge. The man is dressed in a black suit with a black top hat. The woman wears a beige-orange dress with red socks. The man teaches the woman some new moves of the can-can dance. In the foreground is an mysterious, unknown woman in an elegant pink dress. A group of dressed-up people, most of which are men, surrounds the dancing couple. These people engage in conversations, look at the dancing couple, or just hang out on the bar in the background. Toulouse-Lautrec knew most of the people in the Moulin Rouge as he was a regular there. Toulouse-Lautrec used a combination of plain colors with some bright colors to take the viewer on a journey through the Moulin Rouge. Most viewers start by looking at the woman in pink in the foreground, look at the dancing couple next, and then look at the man in the bright red jacket in the background. The light in this painting is provided by the electric chandeliers on the ceiling. This painting is lauded for its beautiful composition. Backstory: After Toulouse-Lautrec completed the painting, the owners of the Moulin Rouge bought it and put it on display on top of the bar. An inscription on the back of this painting reads: “The instruction of the new ones by Valentine the Boneless.” This identified the dancing man as Valentin le Désossé (which means ‘the boneless’). He was a star can-can dancer at the Moulin Rouge. Valentin le Désossé was the stage name of Jacques Renaudin. He had a slim build with long arms and legs, giving him the perfect body for a can-can dancer. He was very elastic and could perform the expressive can-can dance moves with unequalled grace. He did not accept money for his dance performances as he did it for the love of dancing. The woman dancing with Valentine is Louis Weber, a popular dancer from that period. She was so flexible that she could keep her body straight while standing on a single leg and with the other leg raised above her head. What is the Moulin Rouge? The Moulin Rouge is a cabaret and nightclub in Paris established in 1889. As its French name suggests, the Moulin Rouge is a building with a large red windmill on top of it. It is the birthplace of the modern can-can dance. The Moulin Rouge provided entertainment for all layers of society. The extravagant shows, innovative and unique interior, and the world-famous dancers performing there were the key ingredients for the immediate and lasting success of this place. Below is an image of an 1891 poster to advertise the Moulin Rouge by Toulouse-Lautrec. The Moulin Rouge is still open to visitors today.

What is the can-can dance? The can-can (or cancan) is a dance developed in France in the first half of the 19th century. It is a high-energy dance originally performed by both sexes. It involved kicking the legs above the head, splits, and cartwheels (check out this video). It developed over time into a dance mainly performed by women. The female dancers used an elaborate and provoking routine with their long skirts.

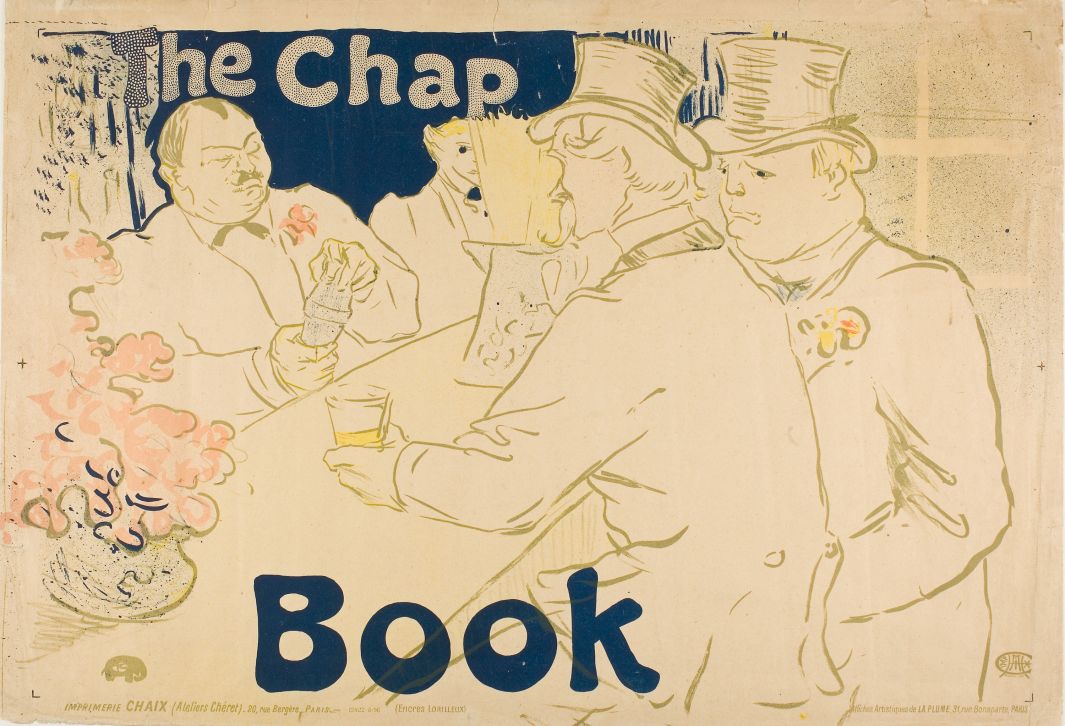

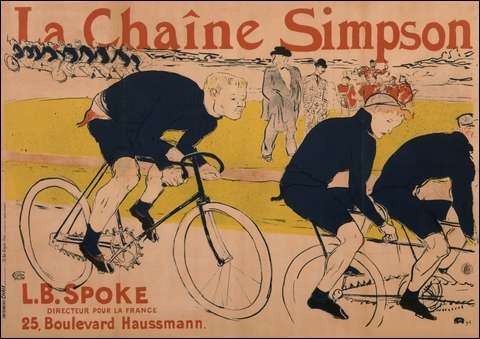

In the 19th century, the can-can was considered a scandalous dance and it was often performed by prostitutes. However, its status improved over time and by the time the Moulin Rouge opened, there were professional can-can dancers that could make could make a living dancing full-time. Who is Toulouse-Lautrec? Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (1864-1901) was born in the South of France and was the first child of a wealthy family. From a young age, his artistic skills were present, and he developed himself into a very productive artist. Toulouse-Lautrec is an important representative of the Post-Impressionist art movement, together with artists like Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, and Van Gogh. Unlike some of these other painters, Toulouse-Lautrec could sustain himself by making advertising posters for nightclubs and other businesses. Two of those posters are shown below. The first is an 1895 advertisement for the American literary magazine The Chap-Book. The second poster is from 1900 and advertises a Simpson bicycle chain.

Fun fact: The parents of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec were first cousins and as a result Toulouse-Lautrec suffered from serious health problems throughout his life. One health problem he faced was that his legs stopped growing as a child and, as a result, he became only 4 ft 8 in (1.42) tall.

His atypical stature (the legs of a child combined with the torso of an adult) led to a lot of mockery from other people and Toulouse-Lautrec resorted to drinking a lot of alcohol. To make sure that he always had a supply of alcohol with him, he had a hollow cane – which he needed to walk – filled with alcohol. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas

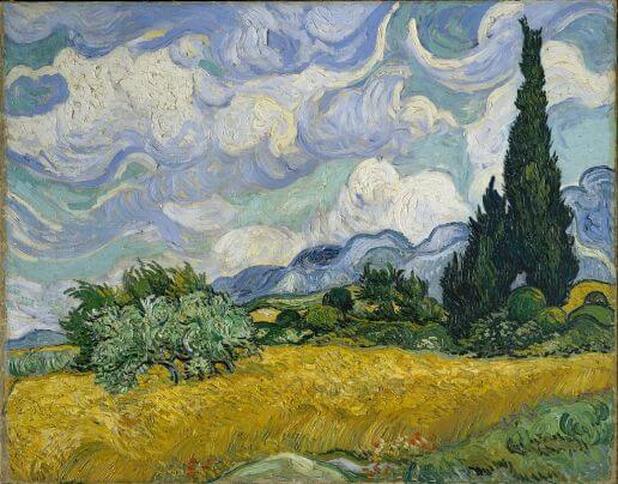

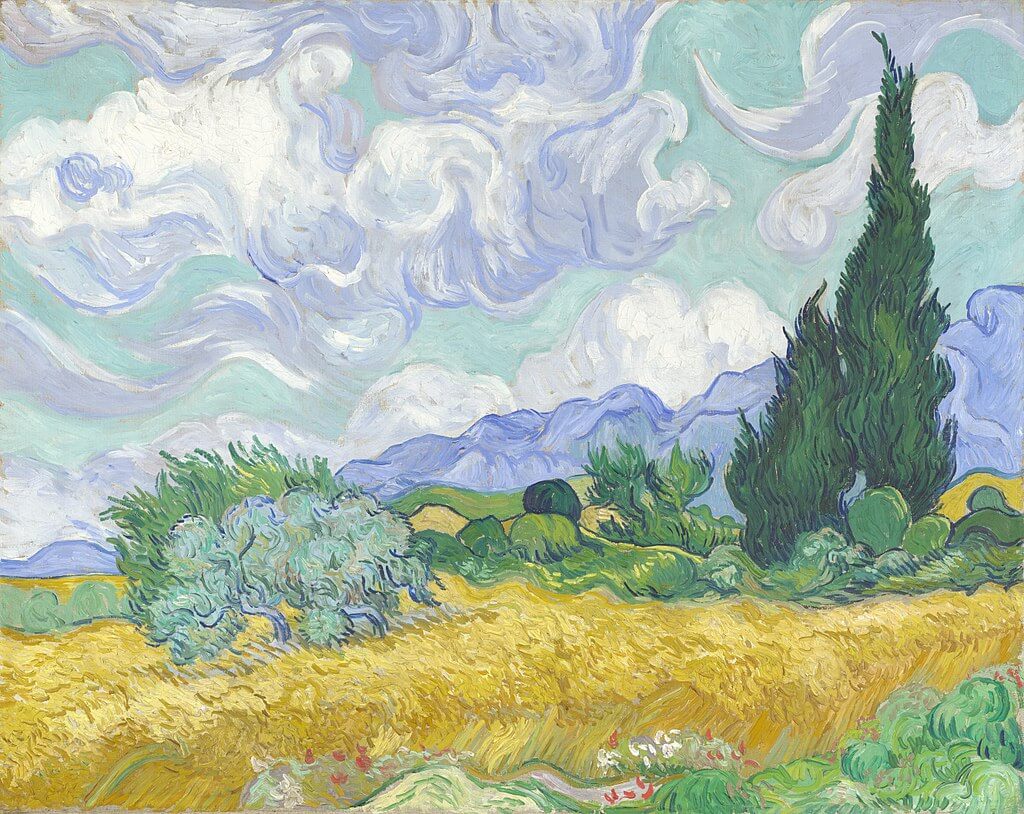

The painting shows a large ripe gold-colored wheat field which is ready for harvest. On the right are two darker cypresses that draw the attention. To the left are lighter and smaller cypresses. The whirling clouds and blue mountains in the background complete this landscape. You can almost feel the wind that is affecting the clouds and the wheat field. This movement is emphasized by the impasto technique used for this painting, in which the paint is applied in thick layers.

Backstory: Van Gogh painted this wheat field (by some referred to as a cornfield) with cypresses when he was in a mental asylum in Saint Remy in the south of France. He painted this when he was allowed to make short walks and paint outside of the asylum. He was particularly impressed by the cypresses he saw there as he felt that this tree reflected some of his emotions. Van Gogh liked this painting so much that he repeated this painting three more times. One version is in the National Gallery in London (and was acquired in 1923 for ₤300, which was similar to the price of a house at that time). Another (smaller) version is part of a private collection. The last version (a pen drawing) is in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

Symbolism: Van Gogh used his paintings to express his ideas of the meaning of life. The wheat fields represent the cycle of life, where people celebrate their growth, but at the same time are susceptible to the powerful forces of nature. The cypresses are a symbol of stability in a wild landscape (though at the same time the cypress was associated with cemeteries and death in the south of France, though many believe that this was not the intended meaning of the cypresses for Van Gogh).

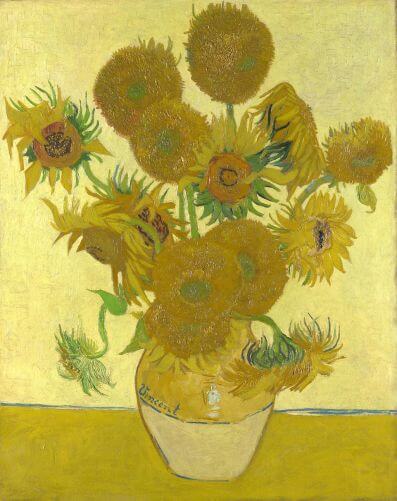

Who is Vincent van Gogh? Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890) was born in The Netherlands. His work is classified as Post-Impressionism and includes landscapes, portraits, self-portraits, and still lifes. Well-known are his depictions of cypresses, sunflowers, and wheat fields. In 1886, Van Gogh moved to Paris, where he connected with the French Impressionists, such as Paul Gauguin and Claude Monet. In 1888, Van Gogh moved further south in France to Arles where he painted his famous series of sunflower paintings, including the version that is in the National Gallery in London. A year later he moved to a nearby mental asylum in Saint Remy, due to his poor mental state, but continued to produce his paintings. During this time, he produced not only this painting but also The Starry Night which is in the Modern Museum of Art in New York. Van Gogh was a heavy drinker and smoker, and his mental state is often reflected in his paintings. In 1890, Van Gogh died at 37 years old from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

What is post-impressionism? Post-Impressionism is a French art movement which developed in response to Impressionism. It is an extension of Impressionism, which is characterized by paintings with bright colors, real-life subject matters, and a thick application of paint.

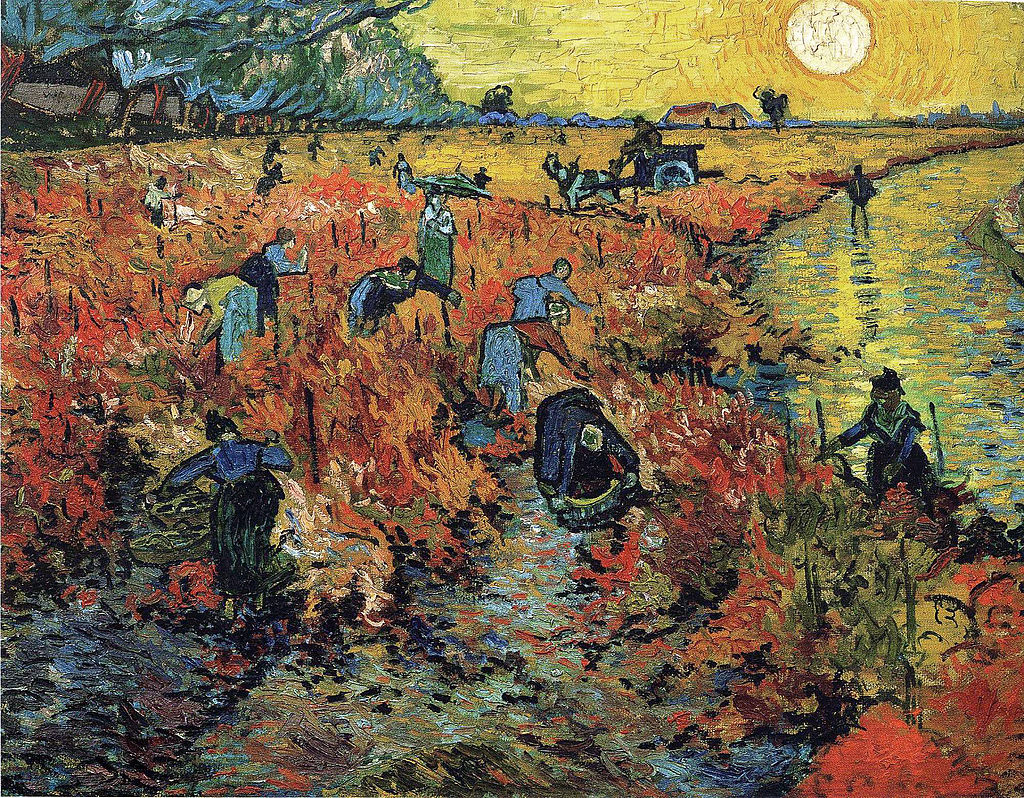

Post-impressionism extended on Impressionism by adding emotions and symbolism to the paintings to reflect the artist’s state of mind. Besides Van Gogh, well-known painters in this movement include Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Paul Cézanne. Fun fact: On the list of the 100 most expensive paintings ever sold, Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol, and Vincent van Gogh are best represented. Van Gogh has most paintings on this list (at least seven). For example, Wheat Field with Cypresses was bought in 1993 for $57 million and donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. But unlike Picasso and Warhol, Van Gogh did not get rich during his life. In fact, the only known painting that Van Gogh sold during his life, The Red Vineyard, was sold for 400 Belgian Francs, which is worth about $1,500 nowadays. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas (Amazon links)

Where? In the Museum of Modern Art, but currently not on display.

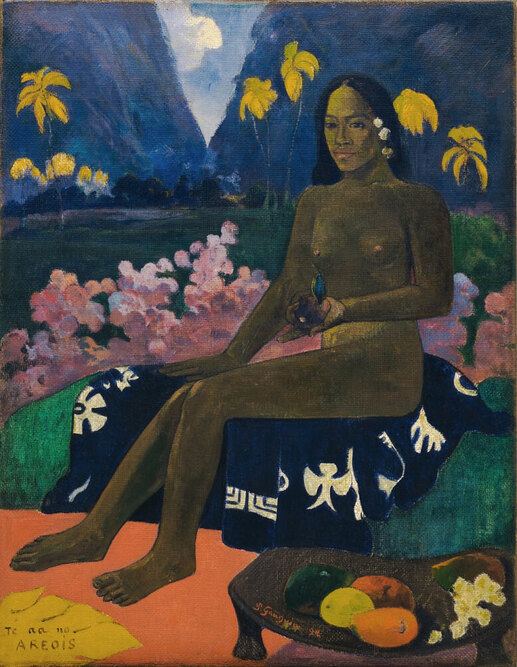

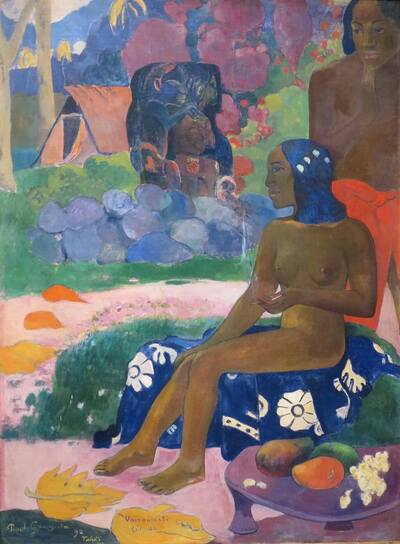

When? 1892 What do you see? A nude girl from Tahiti sits on a blue and white blanket. She is sitting in a dignified position with her back very straight, like the old Egyptians depicted people in art. She has some white flowers in her hair and in her left hand she holds a flowering mango (seed) that she seems to offer to the viewer. This flowering mango symbolizes fertility and was the sacred fruit of the Areoi society. On the bottom right is a three-legged table (called an umete in Polynesian) with more mangos in different colors. The girl is sitting against a background of pink flowers. In the background is the beautiful landscape of Tahiti which shows some mountains, water, trees, and a piece of the sky. Gauguin kept this painting relatively simple and did, for example, not include any shadows. He created a very colorful painting where the colors are not all very realistic. Backstory: This painting is also known under the Polynesian title Te Aa No Areois as can be seen in the bottom left corner. The painting was bought in 1936 by William S. Paley, a trustee, and the later president of the Museum of Modern Art. It was the first Gauguin painting acquired by the MoMA. Gauguin signed and dated the painting on the left side of the table with fruit in the foreground. The composition of the painting is similar to another Gauguin painting entitled Her Name is Vaïraümati (or Vairaumati Tei Oa) which is in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. This painting deals with a similar theme, which is the origin of the Areoi society.

Who are the Areoi? Also referred to as the Arioi, it is a secret religious society in French Polynesia which does not exist anymore. At its origin is a myth about the god Oro who has intercourse with the most beautiful woman on earth, Vaïraümati, which results in the creation of a new race. The society had a hierarchical structure with several classes or ranks. While everyone, both men and women, could theoretically enter into each class within the Areoi, the highest classes were in practice mainly accessible for people from the higher classes of society. The highest class was reserved for priests.

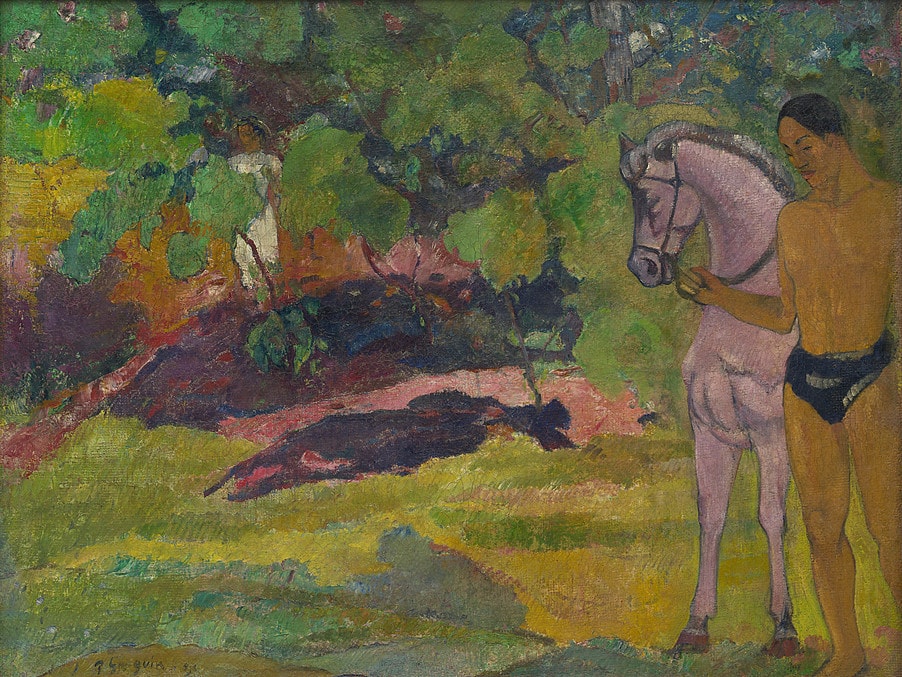

Access to the society depended on your beauty, religious knowledge, recitation skills, and dancing skills. Moving up through the ranks was confirmed by increasingly large tattoos. Members of the society had sexual freedom until they married and were not allowed to get children. Most of the French Polynesian islands had their Areoi order, and they all had a place of worship and several houses in which the members met and where members of the other islands could stay. Who is Gauguin? Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) was a Post-Impressionist artist from Paris. He was a self-taught painter without any formal education. He spent a large time of his youth in Peru where he developed his taste for traveling and exotic countries. In 1891, he moved to Tahiti in French Polynesia where he stayed until 1893 when he temporarily moved back to France. In 1895, he returned to Tahiti where he spent most of his time until his death in 1903. Gauguin is widely known for the idyllic and colorful paintings he made in French Polynesia. His work has had a big influence on artists such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. Other well-known works of Gauguin from his first period in French Polynesia are Hail Mary in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and In the Vanilla Grove, Man and Horse in the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Fun fact: The girl in this painting is the Tahitian mistress/wife of Gauguin. Her name is Tehura, and she is 13 years old at the time of this painting. Soon after this painting, she was pregnant. She is depicted as Vaïraümati, the wife of the god Oro, who gave birth to a son who formed the beginning of the Areoi.

Gauguin wanted to paint the origins of this secret society which he claimed to have learned from Tehura. However, it is now assumed that Gauguin learned about this society through a travel book by Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout. In fact, Tehura was not aware at first that she was depicted as the mother of the Areoi. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster of canvas. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us