|

Where: Rivera Court C200, Level 2 (formerly Garden Court) of the Detroit Institute of Art.

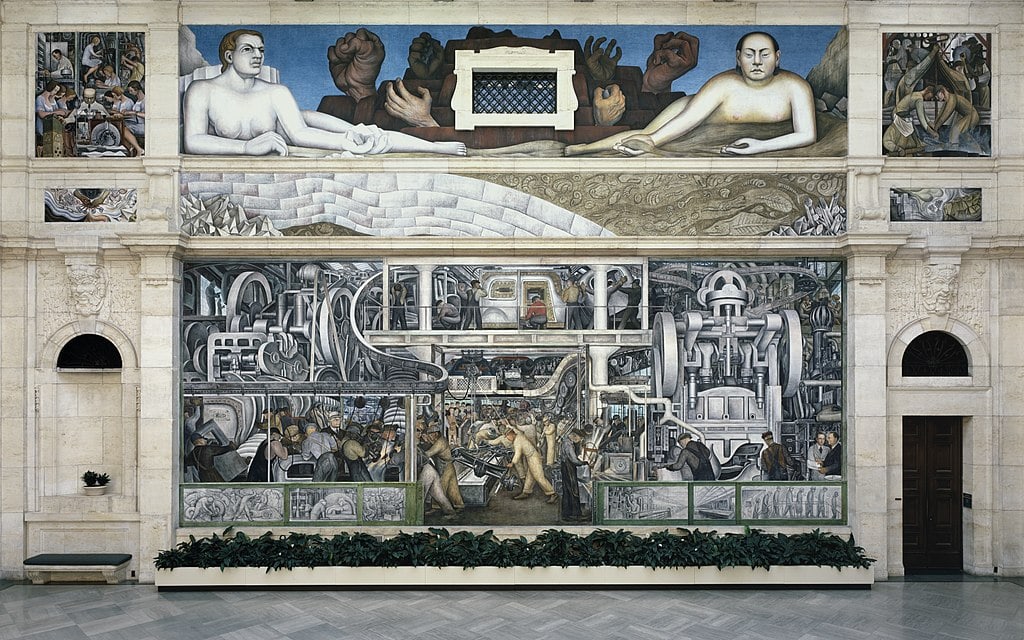

When: 1932-1933. Commissioned by: Edsel Ford and Wilhelm Valentiner What do you see? On four walls of the court, Diego Rivera painted 27 panels with highly allegorical scenes pertaining to the history of Detroit and the development of its industry. The dominant theme is the auto industry and its place in the city’s life. Many panels depict the lives and work of the workers of the Ford Motor Company. The murals are full of symbolism and address questions like how to achieve the balance between the use and abuse of both nature and people. And the symbolism of the murals begins with their layout.

East Wall: This wall faces the sunrise, consistent with the new dawn, new beginning, new life in which man and nature are in harmony. The scene has a child in the center, placed in the bulb of a plant and shielded by roots, fruits and vegetables native to Michigan. Both ends of the main scene lead to the upper panels featuring large nude figures holding grain and other goods of the earth symbolizing both the giving nature and appreciation of humans.

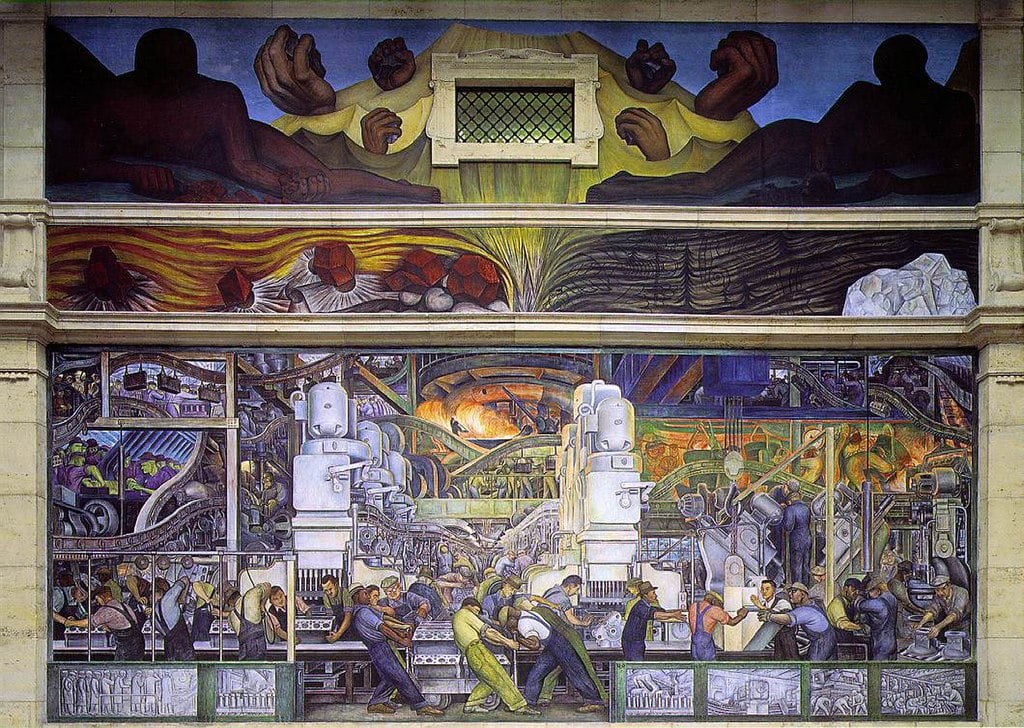

North Wall: This wall relates to darkness or the inner side of reality. In this case, the reality is human work represented by the auto workers building a car. Above the many figures engaged in the variety of tasks are the orange and red of the giant furnace which is blasting fire. The conveyer belts and assembly lanes are attended by the muscled-up men around the two milling machines, which, in turn, direct the viewer’s eye deep into the composition and towards the glazing furnace; here steel is melting for the molds of parts—the soon-to-be automobiles. The art here is more direct and representational.

South Wall: This wall delves back into symbolism. Central to the understanding of the scene is the stamping press, located on the right side of the wall. If one considers Rivera’s Mexican background and the allegorical character of many of his murals, the resemblance of the shape of the press to that of Coatlicue -- the Aztec earth-mother goddess, who lived off human hearts -- becomes apparent. The deity oversaw both creating and annihilating life.

In the context of the Detroit Industry Murals, Coatlicue ruled and gave meaning to the sacrificial character of the factory work. The finished car in the upper mid-section gives the illusion of completeness, but there is more… West Wall: This wall completes the cycle; it also contrasts with the serene character of the southern wall. Here, the bombers and planes warn of the dual nature of the technological advancements. The west wall faces sunsets and symbolizes finality. Smaller panels: In addition to the scenes on the main planes of the walls, there are numerous smaller panels. For example, the upper north and south panels show large figures in different colors, recognizing the value of diversity in the workforce (red for iron ore, white for limestone, yellow for sand and black for coal and diamond). Each color corresponds with the material used for auto manufacturing; each has a value of its own and is indispensable like the representatives of the many races, who are all in the task together. The materials symbolize the strengths of each race. Another smaller panel on the upper right side of the north wall features a baby being vaccinated, held by the parents accompanied by three men. A horse and a cow help decipher the symbolic reference to the nativity scene. Background: Some allegories in the murals were perceived as controversial. For instance, the nudes present on panels were thought to be pornographic, the nativity scene was read as blasphemous, and the idea that a multiracial workforce was a positive thing was not shared by everyone in the United States. Additionally, Rivera’s political views were visible in most of his works. As a staunch communist, he was one of the founders of the Mexican Revolutionary Union of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, in 1922. Another mural by him, Man at the Crossroads (1934), in Rockefeller Center in New York City, was removed in 1934 after it was discovered to have featured Vladimir Lenin and the Soviet May Day Parade. The Detroit Industry Murals have survived mainly thanks to the support of Edsel Ford, the son of Henry Ford and president of the Ford Motor Company. But the decision only followed the uproar of protests from the Catholic Church, students, workers, attacks by the press and the Detroit City Council’s debate on their fate; thousands of signatures had been signed under the petition to destroy them. Who is Rivera? Diego Rivera was born on December 8, 1886 in Guanajuato, Mexico and died on November 24, 1957 in Mexico City. He showed strong artistic talent early in life. He attended the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts when he was approximately 12 years old, finishing it in 1905. The government sponsored his intense, long travel-study through Europe where he met several prominent artists, including Modigliani who painted a portrait of him. He showed six paintings in the 1910 exhibit sponsored by The Society of Independent Artists in Paris. Rivera's style evolved quickly; after initial impressionistic marks present in the Breton Girl and House Over the Bridge, Rivera absorbed Cubism fully by 1913. His trip to Italy in 1920 resulted in fascination with the Renaissance fresco. When he returned to Mexico, the fascination translated into mural painting, for which he is now arguably best known. Diego Rivera’s political life was colorful and an integral part of his art. The Mexican Revolution and the Revolution of 1917 sealed forever his staunch devotion to communism and belief in the revolutionary mission of arts. But his many commissions in the United States were among reasons, for which he was also called by many a charlatan and a “millionaire artist for the establishment.” Rivera was expelled from the party in 1929, for disloyalty to the Comintern, but, in reality, for the catch-all sin of Trotskyism. Leo Trotsky lived with Rivera for some seven months in the 1930s while in exile. He is featured in Arsenal along with Rivera’s third wife, Frida Kahlo.

Fun fact: The Detroit Industry Murals were finished in a relatively short period of time; after about a month of preliminary drawings, Rivera started to work on them in July 1932 and finished in March 1933.

One of the most intriguing friendships Rivera developed during that time was with Edsel Ford, son of the Ford Motor Company founder and president. He was anti-communist, anti-union and pro-business magnate of capitalism, yet he is the one who paid for a substantial part of the Detroit Industry Murals.

0 Comments

|

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us