|

Where? Room 67 on Floor 0 of the Prado Museum

When? 1820-1823 What do you see? The power-hungry god of time, Saturn, stands in the darkness with the corpse of his son in his hands. His grotesque limbs are abnormally long and twisted. The yellow color of his skin gives him a sickly and monstrous appearance. With a mouth as wide as his eyes, he bites pieces of flesh out of his son’s body. The head and right arm have already been devoured. The corpse hangs limp in his firm hands, fingers digging into the back. Surrounded by muted colors and a black background, the blood flowing out of the son’s body is particularly striking. Slowly, the background seems to obscure Saturn’s body as the shadows slowly swallow his right elbow and thighs. Backstory: In his villa outside of Madrid, Goya created a series of disturbing images which have since been dubbed his Pinturas Negras or Black Paintings. Painted towards the end of his life, these paintings reflected Goya’s pessimistic view towards humanity. The works deal with dark and disturbing themes. One of the most iconic works of this dark series was Saturn Devouring His Son. The painting was created in his dining room, perhaps in response to the Napoleonic Wars which took place towards the end of his life. Witnessing the Spanish government at its worst, Goya was heavily concerned with topics such as abuse of power and violence. Another example of Goya’s black paintings is Witches’ Sabbath which is also on display in the Prado Museum.

The Myth of Saturn: In Greek and Roman mythology, Saturn was the son of Caelus, the god of the sky. When he realized that Caelus’s rule was tyrannical, Saturn overthrew his father and took his place as a supreme leader. Saturn and his wife, Ops, were soon expecting six children. However, it was prophesied that one of these children would overthrow him, granting him a fate not unlike that of Caelus.

In an effort to escape this fate, Saturn devoured five of his children as soon as they were born. Horrified, Ops hid the sixth child, Jupiter, from Saturn and replaced him with a stone wrapped in cloth. Saturn ate the stone and as it passed through his system, it freed the five children that he had swallowed. Later, Jupiter would indeed overthrow his father as a supreme leader and Saturn fled to Latium where he became a god of agriculture. Who is Francisco Goya? Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes was born in 1746 in Fuendetodos in the Northeast of Spain and died in 1828 in Bordeaux, France. He studied drawing and painting in Zaragoza and joined the studio of José Luzán. Later, he studied under Francisco Bayeu Subías who led him to work on decorations for the royal palace. Goya married Subías’s sister and traveled to Italy after failing in two drawing competitions at the Real Academia des Bellas Artes in San Fernando. Eventually, Goya was appointed painter to the Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid. His work was reminiscent of Rococo art and focused on day-to-day events. As his work gained more attention, Goya rose to the position of court painter to King Charles III and King Charles IV. Around this time, he began to travel Andalusia to study realism. He was commissioned by the Spanish Court to paint some anti-war pieces such as The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808. Goya lived in a villa outside of Madrid called Quinta del Sordo which used to belong to a deaf man. In the later stages of his life, Goya fell ill to an unknown sickness and suffered a hearing loss of his own. Along with his physical health, Goya’s mental health went into decline. Living through major turmoil in Spain, Goya’s outlook on life became very pessimistic and his work became dark and deeply disturbing. The walls of his villa were covered in murals of “Black Paintings’ which have since been transferred onto canvas and moved into the Prado Museum.

Fun fact: Saturn Devouring His Son is believed to have been inspired by Peter Paul Rubens’ Saturn which was painted in the 1630s. Rubens’ depiction of Saturn appears to have more consciousness and awareness of his decision of eating his son. Goya, on the other hand, depicts Saturn as completely lost in chaos and fear, consuming his child as if it were necessary for his survival.

0 Comments

Where? Room 64 of the Prado Museum

When? 1814 Commissioned by: The Spanish government What do you see? A scene of a street fight. Napoleon’s Turkish soldiers, the Mamelukes, ride on horses, arms raised with swords. They are recognizable in their turbans and black uniforms. Some of them wear blue shirts and red pants. On the ground are the outnumbered citizens of Madrid. They are peasants and common people recognizable by the dull rags that they wear. A man that appears to be a Spanish soldier stands on the right side in a black uniform. He points his gun towards one of the Mamelukes. In the foreground, a man stabs a white horse as another man on the left raises his arm to stab its rider. Beneath the horse are two dying rebels. Behind, a peasant tackles a Mameluke, jumping off the ground to attack. The numerous blurred faces in the middle ground add to the chaos of the scene. Although the scene looks like a Spanish triumph, the reality of the story is not so. Backstory: This painting commemorates a true historical event. In this work, Goya shows one of many street fights that broke out on the second of May, 1808, when Spanish citizens rebelled against the French occupation. The Spanish people that rebelled during that day were executed by French firing squads on the next day, and Goya captured that event in a separate painting called The Third of May 1808 which is also in the Prado Museum. The painting of The Second of May 1808 is crammed with the bodies of Mamelukes, Spaniards, and horses that tangle to make for a very chaotic scene. The moment is dramatized with the harsh light on the white horse in the center of the painting and the subtle diagonal drawn from the cadaver (bottom left) to the two soldiers with raised weapons (right of center). The work also uses lighter colors and bright reds that put it in direct opposition to The Third of May 1808, which uses darker tones. Goya puts an emphasis on the sacrifice of the Spanish rebels, showcasing their heroism.

May 2, 1808: This was the day that many citizens of Madrid rebelled against the French occupation. Crowds assembled around the Royal Palace of Madrid to protest the French occupation. The French soldiers opened fire on the crowds, triggering street fights and rebellion in other parts of the city. The French armed forces outnumbered the Spanish citizens. When the conflict had subsided, hundreds of Spanish citizens had died. Many survivors were taken prisoner for execution the next day.

May 3, 1808: The day after the Spanish rebelled against the French army, the rebels were executed by French firing squads. Many surviving Spanish rebels were gathered and shot in several locations in Madrid. Supposedly, most of the executed rebels were peasants, artisans, and beggars. About one hundred deaths by firing squads were reported. Goya captured the events on this day in his painting The Third of May 1808, which is also in the Prado Museum. Who is Goya? Francisco Goya was born in 1746 in Fuendetodos in the Northeast of Spain and died in 1828 in Bordeaux, France. He studied drawing and painting in Zaragoza and joined the studio of José Luzán. Later, he studied under Francisco Bayeu Subías who led him to work on decorations for the royal palace. Goya married Subías’s sister and traveled to Italy after failing in two drawing competitions at the Real Academia des Bellas Artes in San Fernando. Eventually, Goya was appointed painter to the Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid. His work was reminiscent of Rococo art and focused on day-to-day events. As his work gained more attention, Goya rose to the position of court painter to King Charles III and Charles IV. His style was cheerful and warm and included paintings like The Parasol in the Prado Museum. But around 1793, he fell ill and became deaf. After this, Goya’s work became filled with darkness, ghosts, and monsters. An example of such a dark painting is Saturn Devouring His Son, which is also in the Prado Museum.

Fun fact: During the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939, the collection of the Prado Museum was moved to the League of Nations in Geneva. The truck transporting some of Goya’s works was caught in an accident as it was passing through Girona. The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808 were stored together, and both suffered quite a blow. However, The Second of May 1808 suffered more damage. In the process, the canvas of this painting was damaged. Small pieces of the canvas fell off the left side and were lost on the road. Tear marks and scratches are still visible on the left side of the work despite restoration efforts in 1941, 2007, and 2008.

Where? Room 64 of the Prado Museum

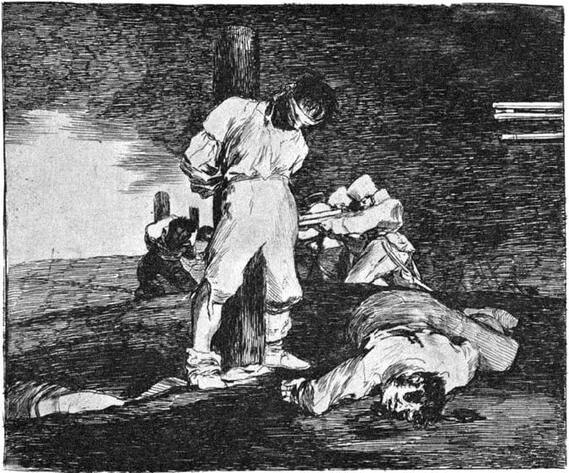

When? 1814 Commissioned by: The Spanish government What do you see? A group of French soldiers on the right point their rifles at a Spanish peasant dressed in white. The French firing squad is about to execute the peasant who stands against a hill with his arms raised like a Christ figure in surrender. At his feet are some of his comrades who have been slaughtered by the firing squad, their blood still running on the dirt. And surrounding them are other people that are next in line to face the firing squad. Some of them cover their eyes as they do not want to witness the gruel scene in front of them. Among the people surrounding the man in white is also a bold-headed monk. He is directly to the left (from our point of view) of the man in the center, and he has his hands clasped in prayer, avoiding the eyes of the soldiers. Backstory: This painting is a commemoration of a true historical event, Napoleon’s French army invading Spain. This painting shows a particular scene that occurred on May 3, 1808, when the French army decided to execute Spanish citizens that rebelled against them. Francisco Goya was deeply affected by this series of events and decided to create this painting to show the injustice of the French army’s actions. Goya has dramatized the moment. The square lantern in the center pours bright light onto the rebels on the left and the man dressed in white. Goya gives him a Christ-like aura with his arms raised in golden light. The man is made into a martyr while the French soldiers are left anonymous and thus soulless. May 2, 1808: This was the day that many citizens of Madrid rebelled against the French occupation. Crowds assembled around the Royal Palace of Madrid protesting French occupation. The French soldiers opened fire on the crowds, triggering street fights and rebellion in other parts of the city. The French armed forces outnumbered the Spanish citizens. Goya captured the events on this day in his painting The Second of May 1808, which is also in the Prado Museum. The painting depicts the Mamelukes (Napoleon’s Turkish soldiers) in a street fight with Spanish rebels. When the conflict had subsided, hundreds of Spanish citizens had died. Many survivors were taken prisoner for execution the next day.

May 3, 1808: The day after the Spanish rebelled against the French army, the rebels were executed by French firing squads. Many surviving Spanish rebels were gathered and shot in several locations in Madrid. Supposedly, most of the executed rebels were peasants, artisans, and beggars. About one hundred deaths by firing squads were reported.

Who is Goya? Francisco Goya was born in 1746 in Fuendetodos in the Northeast of Spain and died in 1828 in Bordeaux, France. He studied drawing and painting in Zaragoza and joined the studio of José Luzán. Later, he studied under Francisco Bayeu Subías who led him to work on decorations for the royal palace. Goya married Subías’s sister and traveled to Italy after failing in two drawing competitions at the Real Academia des Bellas Artes in San Fernando. Eventually, Goya was appointed painter to the Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid. Goya's work was reminiscent of Rococo art and focused on day-to-day events. As his work gained more attention, Goya rose to the position of court painter to King Charles III and Charles IV. Around this time, he began to travel Andalusia to study realism. When he returned from his trip, he had fallen ill and gone deaf. Before the decline of his health, much of Goya’s work had been cheerful and warm. After losing his hearing, Goya’s work became dark and filled with monsters, darkness, and ghosts. Witches’ Sabbath in the Prado Museum is an example of such a dark work. It is part of his series of fourteen Black Paintings.

Fun fact: Before painting The Third of May 1808, Goya had worked on a series called The Disasters of War. These gruesome prints showed the violence, gore, and fear that comes from war. Without taking a side in the conflict, Goya expressed great anti-war sentiment. The prints were not published until decades later.

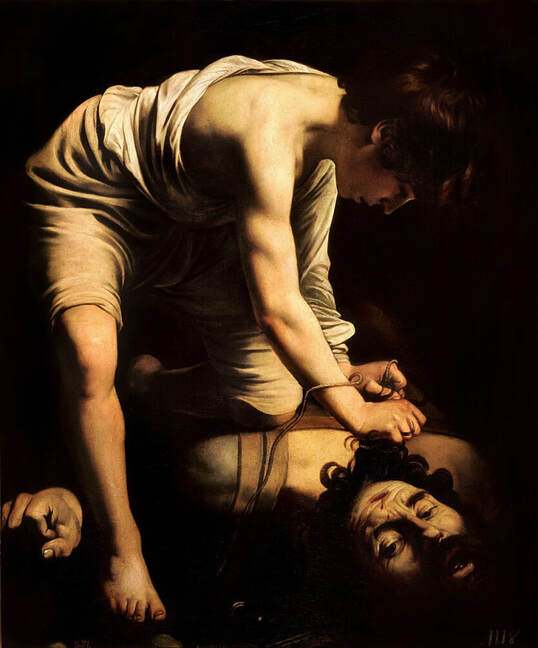

Where? Room 6 of the Prado Museum

When? Around 1600 Commissioned by? Unknown What do you see? David is tying the hair of Goliath with a rope after he beheaded him. This would allow him to carry the head with him and show it as proof that he killed Goliath. David wears a white fabric that he tucked into his beige pants. He bends down with his left knee on top of the shoulders of the beheaded body of Goliath. David is concentrated on his task and does not show any sign of triumph. It seems a serious and necessary task that he is completing. On the left, we can see the large right hand of the giant. Goliath has thick curly hair and a black beard. We can also see the wound on his forehead where the stone from David’s sling hit him. Caravaggio created a strong contrast between light and dark to emphasize the important body parts in this painting. The right leg, back, and arms of David are in the light, as are the head, shoulders, and right hand of Goliath. Backstory: The exact date that Caravaggio painted this work is unclear, but experts believe that he created this between 1596 and 1600. The painting was taken to Spain after Caravaggio completed it. There, it had a big impact on the Spanish artists of that time. This painting is based on the Biblical story of David and Goliath in 1 Samuel 17. However, this story does not mention that David used a rope to tie the hair of Goliath. This is just a free interpretation of the Biblical story by Caravaggio. Other versions by Caravaggio: Caravaggio painted David with the Head of Goliath a total of three times at different stages of his career. In 1607, he painted his second version, which is on display in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. In this version, David grabs the hair of Goliath to hold his head in his hand. The third version from 1610 is in the Galleria Borghese in Rome. The second and third versions are quite similar. The main differences are the age of the head of Goliath and the way in which David holds his sword.

David and Goliath: 1 Samuel 17 describes the story of David and Goliath. Israel was at war with the Philistines. The Philistines had a hero called Goliath who was over 9 feet (2.75 meters) tall. Goliath proposed every day to the Israelites that instead of letting the armies fight each other, they should send one man to fight him. If Goliath would win the fight, the Israelites would become slaves of the Philistines, and if Goliath would lose, the Philistines would become slaves of the Israelites.

David convinced King Saul that he should fight Goliath. He went out of the army camp to meet Goliath, wearing no armor but bringing a walking stick, a sling, and a bag with five smooth stones. He put a stone in his sling and threw it at Goliath, hitting him between his eyes. Goliath fell, and David took Goliath’s sword to kill him by cutting off his head. He took the head of Goliath back to Jerusalem but kept his sword and spear for himself. Who is Caravaggio? Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610) was born in Caravaggio near Milan, Italy. In 1592, he fled to Rome to escape a conviction in Milan. Around 1600, he became very popular and was probably the most sought-after painter in Rome. He received the most prestigious commissions, and many people enjoyed the contrasts, drama, and emotions he included in his works. In the years after he painted the first version of David with the Head of Goliath, Caravaggio painted several other masterpieces, including The Entombment of Christ between 1602 and 1604 in the Vatican Museums and Death of the Virgin between 1601 and 1606 in the Louvre.

Fun fact: X-ray analysis revealed that Caravaggio initially wanted to paint a much more expressive version of Goliath. Underneath the canvas are traces of another design of the head of Goliath. In that design, Goliath has a much more terrifying expression on his face and his eyes almost pop out of his head. This version was more like the painting of Medusa of which Caravaggio painted two versions. The first version from 1596 is in a private collection and the second version, from 1597, is in the Uffizi Museum. However, the unknown commissioner of David with the Head of Goliath in the Prado Museum probably rejected this initial design after which Caravaggio settled on a more conservative version of Goliath’s head.

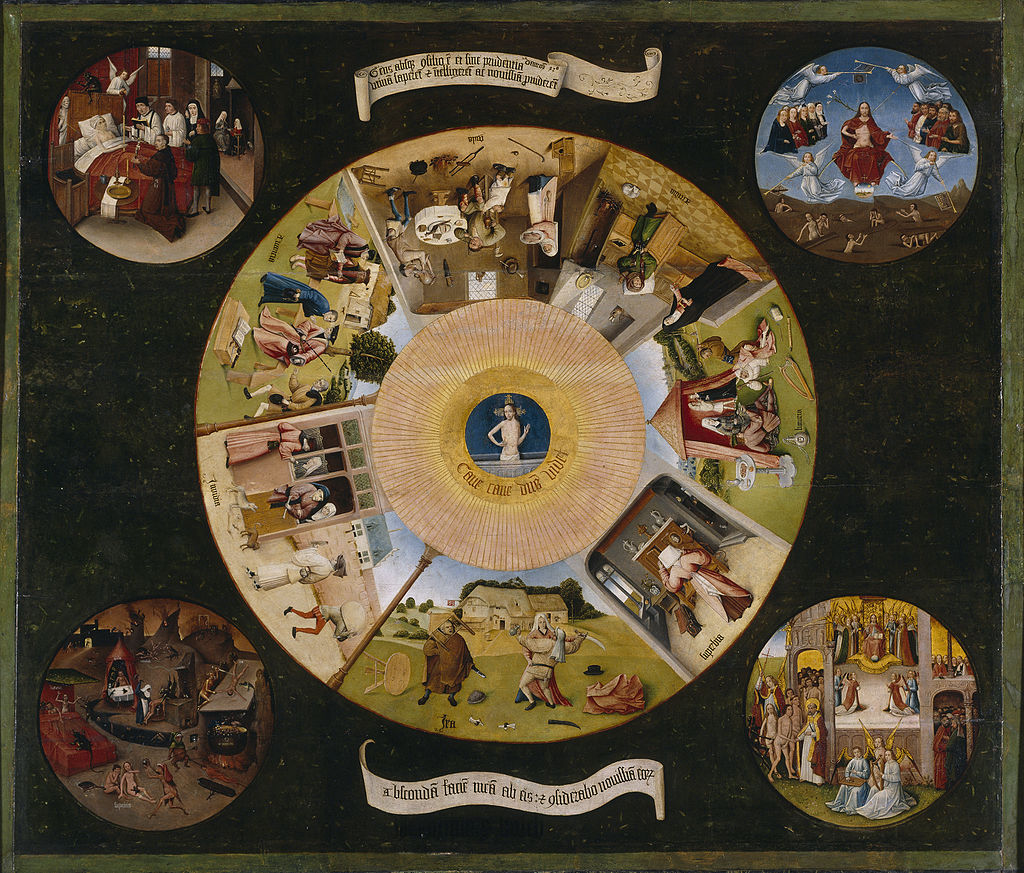

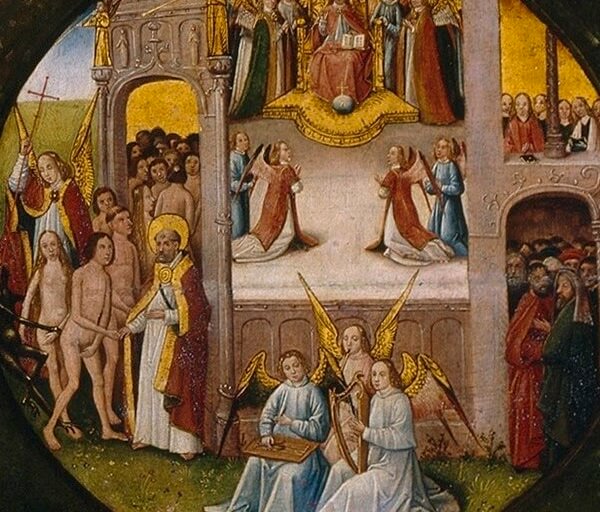

Where? Room 56a of the Prado Museum

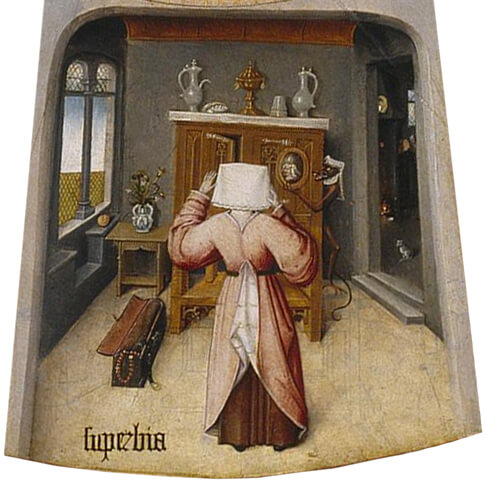

When? Probably around 1500 What do you see? Bosch painted this work on a wooden tabletop. On the outside are four circles with the four things of man, which are the last four stages that the human soul goes through upon death. In the middle is a large circle with scenes of the seven sins. In the center is an image of Christ emerging from his grave with the text ‘Cave cave dns videt’, which means ‘Beware, beware, the Lord sees’. The banderol on the top shows a text from Deuteronomy 32:28 – “They are foolish. They don’t understand. If they were wise, they would understand; they would know what would happen to them.” The banderol at the bottom contains a text from Deuteronomy 32:20 – “I will turn away from them, then let’s see what happens!”. The four last things: The last four things are discussed clockwise starting at the left top.

(Click on each of the images below to enlarge them)

The seven sins: The sins discussed are discussed clockwise starting at the bottom.

(Click on each of the images below to enlarge them)

Fun fact: The Prado Museum claims that Hieronymus Bosch created this painting. However, there is some discussion on whether this claim is valid, as others people believe that this painting is created by one of the followers of Bosch. One argument in favor of Bosch is that the painting contains his name, just below the banderol in the bottom center. An argument against Bosch is that there is already documentation in the 16th century that a pupil of Bosch created this painting and that he either added the name of Bosch out of respect for his master or to increase the value of the painting.

The main reason for doubt, though, is that this painting is not very typical for Bosch. The figures in this painting are somewhat unrefined, something that is not the case in the other works attributed to Bosch. Another reasonable explanation is that Bosch painted this work together with his assistants as some scenes are of higher quality than others. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster.

Where? Room 25 of the Prado Museum

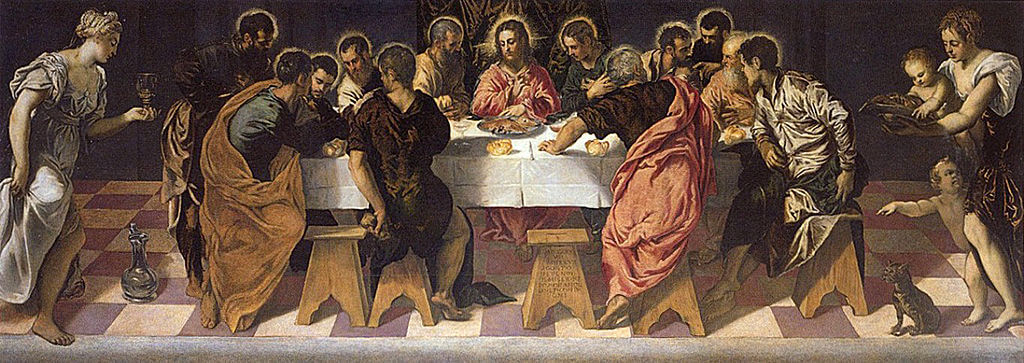

When? 1548-1549 Commissioned by? The Church of San Marcuola in Venice What do you see? On the right, Jesus sits on his knees and washes the feet of his disciple, Peter, who is reluctantly accepting that his master washes his feet. The young disciple, John, helps them by holding a watering can to fill the tub. In line with the Biblical story, Jesus has a towel wrapped around his waist. He has taken off his blue robe, which lies behind him. Scattered around the area are the other disciples. Four of them sit on the table. To the left of the table, one disciple comically helps another one to take of his pants. The disciple in the left foreground and the one to the right of table take off their sandals to have their feet washed. The disciple standing in the background against a pillar is Judas, who is about to betray Jesus after the Last Supper. Behind the head of Jesus, we can see another room with the follow-up scene. In that room are Jesus and his disciples celebrating the Last Supper. In the background, we can see some made-up architecture, based on 16th-century Venice. There is a canal with at the end a triumphal arch. Perspective: To fully appreciate this painting, one should look at it from the right side. So, stand to the right of the painting and you will see that the perspective suddenly is correct and that this is a beautiful piece of work. The composition starts with Jesus and Saint Peter, continues through the middle of the table, and ends at the arch at the end of the water. Notice how the tiles on the floor suddenly have a straight pattern. The reason that one should look at it from the right is that Tintoretto created this painting originally to hang on the right side of the apse (the area where the altar stand) in a Venetian church. Therefore, the churchgoers would automatically look at this painting from the right side. Backstory: This painting is also known as Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet. It is based on the Biblical story in John 13: 1-20, in which Jesus washes the feet of his disciples before they eat the Last Supper. Washing the feet was a common thing before having dinner as the people at that time wore sandals and walked on dusty roads. Typically, a servant washed the feet of the guests before dinner. Tintoretto created this painting for the Church of San Marcuola in Venice. On the left side of the apse hangs the Last Supper by Tintoretto and on the right side hung this painting on Christ washing the feet of the disciples. Today, it is replaced by a copy by Carlo Ridolfi (who also wrote a biography on Tintoretto). The original by Tintoretto entered the collection of the Prado Museum in 1936.

Other versions: Tintoretto loved the theme of Christ washing the feet of his disciples, and he created at least five different versions of it. Just like he did in the San Marcuola Church in Venice, Tintoretto often combined this painting with a painting on the Last Supper.

One version of Christ Washing the Feet of the Disciples hangs now in the National Gallery in London but was originally in the San Trovaso Church in Venice. Another version is in the San Moisé Church in Venice. Yet another version, very similar to the one in the Prado Museum, hangs in the Shipley Gallery of Art in Gateshead, England. It is not completely clear whether the original version in the Church of San Marcuola is the version in the Prado Museum or the Shipley Gallery of Art. A copy by Tintoretto of the Prado version hangs in the Ontario Gallery of Art in Toronto.

Moral: Jesus shows his humility by washing the feet of his disciples. As the leader of the disciples and the Son of God, he wanted to set an example that people are equal and that you are never better than another person.

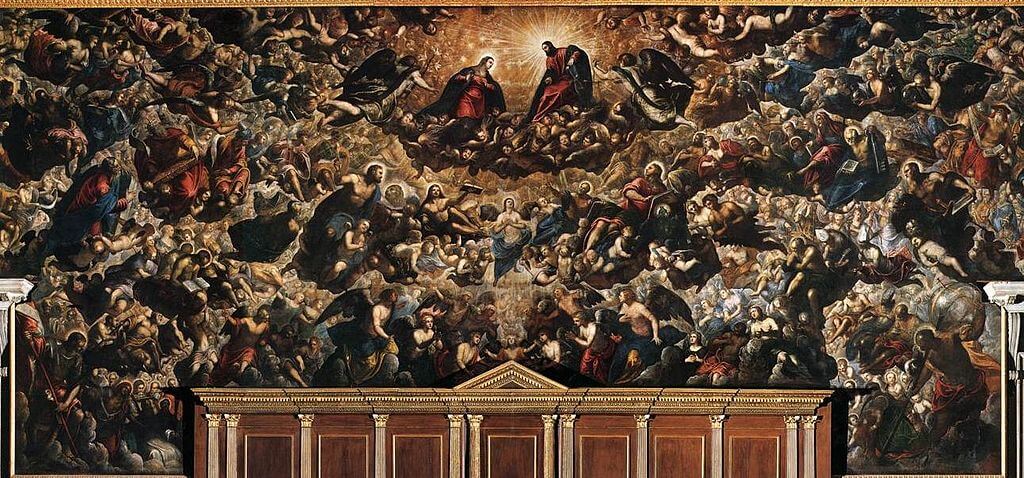

Who is Tintoretto? Jacopo Comin, better known as Tintoretto, was born in 1518 in Venice and died there in 1594. He was a very talented painter. His aim was to combine the Mannerist drawing style of Michelangelo with the use of colors by Titian. This style is exactly what characterizes his work. Tintoretto was the oldest child and had twenty siblings. Tintoretto means ‘little dyer,’ and he was known by that name as his father was a dyer of clothes. Tintoretto was a very energetic and productive painter, and he created a large number of paintings often containing many figures. His masterpiece, Paradise, hangs in the Doge’s Palace in Venice. He started this painting when he was 70 years old, it includes over 500 figures, and measures about 25 x 9 meters.

Fun fact: The paintings contains a few interesting details. First, Judas is shown in the background. He has a halo around his head. This is strange as Judas is about to betray Jesus and halos are used to identify holy or sacred people. While Tintoretto is not the only artist to put a halo around the head of Judas, he is more commonly depicted without a halo, and sometimes with a black or darker-colored halo to separate him from the other disciples.

Another interesting detail is the dog in the foreground. It is not entirely clear why the dog is there. In any case, the presence of the dog caused Tintoretto some trouble. The inquisition thought that this was an unnecessary detail in this painting and this kind of detail was strongly discouraged for religious use by the Council of Trent earlier in the 16th century.

Where? Room 11 of the Prado Museum

When? 1628-1629 Commissioned by? Velázquez created this painting for King Philip IV of Spain and Portugal and received 100 silver ducats for it. What do you see? The bare-chested man with the pale body is Bacchus. He sits on a wine barrel and is crowned with a wreath of vine leaves. At his feet are two jugs. Bacchus is surrounded by peasants wearing 17th-century Spanish clothes. To his right, he welcomes the kneeling soldier wearing a sword by putting a wreath of vine leaves on his head. Meanwhile, Bacchus looks in the other direction. Some of the other people have raised their glasses to welcome the new man. The man with the hat, directly to the right of Bacchus, is holding a big bowl of wine and stares directly at us while laughing. The men to his right, with the hand on his shoulder, is clearly drunk. The kneeling man in the brown cloak in the right foreground raises his glass in honor of Bacchus. The man on the complete right welcomes a passerby taking off his hat to greet the group of people. To the left of Bacchus is a nude satyr (a male companion of Bacchus with horse ears and a permanently erect penis) with a wreath of vine leaves. The satyr holds a full martini glass. The final person sits in the left foreground and also wears a wreath of vine leaves. He is painted in the shadow, probably to enhance the contrast with the pale Bacchus. Velázquez did not put much effort into the background of the painting, which may be because he originally painted this work inside, probably in a tavern. Backstory: This painting is known under various names, depending on what people think the focus of this painting is (and it is also not entirely clear what the motivation of Velázquez for this painting was). The most conventional name is ‘The Triumph of Bacchus’ which refers to Bacchus bringing the gift of wine to the common people to relieve them from their daily concerns. The painting is also known as ‘The Drunkards’ (or ‘Los Borrachos’ in Spanish) which refers to the intoxicated people in this painting. Velázquez created this painting during the time that Peter Paul Rubens, the most famous painter of that time, visited Madrid for nine months. During that time, Velázquez could observe the work and the technique of Rubens. Velázquez realized that he could not compete with Rubens by trying to copy his style and so he kept his own style to remain unique. This painting is also the first time that he included some nudity in his work, something that Rubens did more frequently, such as in Rubens’ Samson and Delilah in the National Gallery in London.

Who is Bacchus? Also known in Greek mythology as Dionysus, Bacchus is the god of wine, winemaking, fertility, and theatre. He is closest to the common people among the mythological gods and is, therefore, a popular subject among artists. He stands for freedom, drinking, and dancing, which has been attractive to many people over the centuries.

Many artists have used Bacchus as a subject of their art. For example, in 1595, Caravaggio painted Bacchus in the Uffizi Museum, and, in 1522-1523, Titian painted Bacchus and Ariadne in the National Gallery in London.

Who is Velázquez? Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez was born in 1599 in Seville and died in 1660 in Madrid, Spain. He became the lead court painter for King Philip IV during his twenties. Besides many painting portraits of well-known people including the Spanish royal family, he created mainly historical paintings. His works did not become very popular outside Spain until the 19th century.

Velázquez has had a big influence on future painters such as Manet, Picasso, and Dali. Over his career, Velázquez constantly improved his painting style, which became more refined and realistic. This ultimately resulted in 1656 in the creation of his best work, Las Meninas, which is also on view in the Prado.

Fun fact: It is interesting to compare this painting to another masterpiece from the same time period. In 1632, Rembrandt painted The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp which is now in the Mauritshuis in The Hague, The Netherlands. Velázquez was about 29 years old when he painted The Triumph of Bacchus and Rembrandt was 26 years old when he painted about the anatomy lesson. The two had never met each other.

Both Velázquez and Rembrandt depicted nine different people and some nudity. The main difference is that the people in Rembrandt’s work are quite static while the people in Velázquez’s work are showing more emotion and feel more real. Both are considered masterpieces nowadays and you can decide for yourself which painting you prefer. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us