|

Where? Gallery 201 at The Art Institute of Chicago

When? 1877 What do you see? A busy, rainy street near the Saint-Lazare station in Paris. The canvas is divided in half by an axis, a tall green streetlamp. Walking on the right of it, in the foreground, are a couple dressed in the latest Parisian fashion. As they walk arm in arm beneath an umbrella, looking off to the left side of the canvas, a stranger passes them with his back to the viewer. Judging by the young woman’s brown dress and diamond earring, the pair are likely of the upper class. The men in the middle ground appear to be dressed in a similar fashion. Further down the canvas are some traces of the working class. Behind the man’s umbrella, a painter dressed in white carries a ladder across the street. Behind the woman, a baker looks out her window. Two carriage drivers can be seen on the left side of the street lamp.

Backstory: Exhibited at the Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877, Paris Street; Rainy Day was celebrated by many. The natural scene of a real Parisian street painted in a realistic fashion calls back to Caillebotte’s interest in photography. However, the painting’s style cannot be characterized as entirely realist or academic.

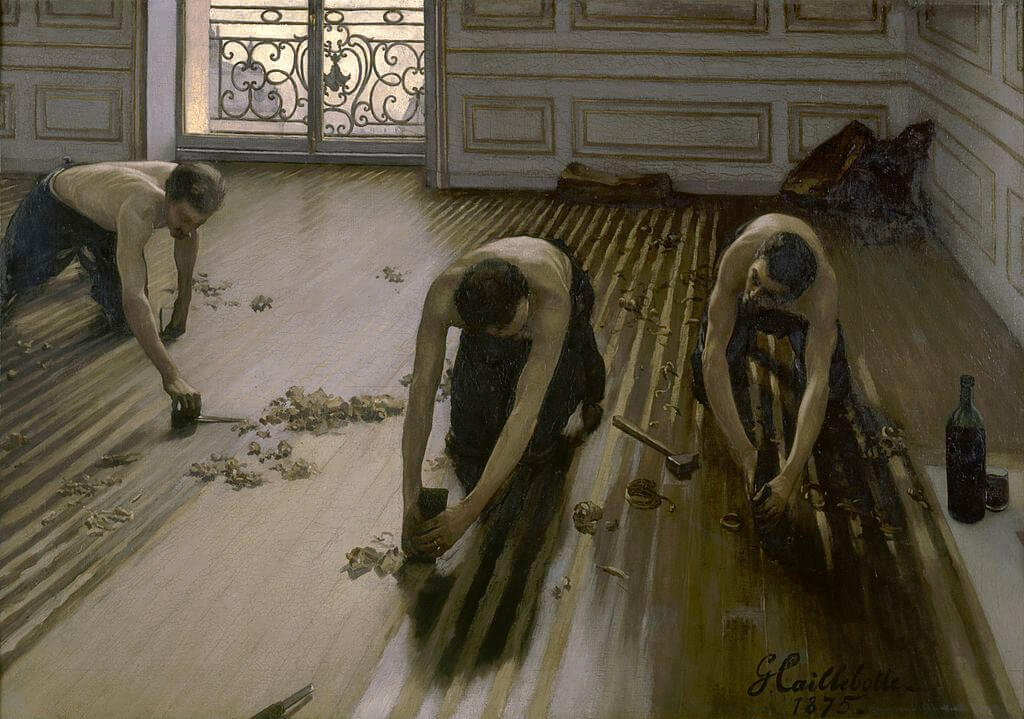

Caillebotte features an unusual asymmetrical composition and cropped figures. On the right side of the canvas, the man and woman’s legs are out of frame and the stranger with his back to the viewer is split in half. This detail may be overlooked by modern viewers but was considered radical by Caillebotte’s contemporaries. The cropped composition may have been inspired by his interest in photography. Featuring unsaturated colors and dim light, the painting has a gloomy and slow feeling. Subtly showing the division between the bourgeoisie and the working class, Caillebotte’s palette suits the daunting disparity that is most heavily felt by the workers. Who is Caillebotte? Gustave Caillebotte was born in 1848 in Paris and died in Gennevillers in 1894. He grew up in a wealthy family and began painting in the studio of Leon Bonnat. In 1873, Caillebotte began his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts and shortly after became acquainted with Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet. With his money, he was able to support many artists like Edgar Degas, Camille Pissaro, and Alfred Sisley. Although he did not participate in the first one, Caillebotte exhibited eight paintings in the Second Impressionist Exhibition of 1876, one of which was The Floor Scrapers in the Musée d’Orsay. Caillebotte’s academic style combined with an Impressionist influence produced a unique and modern style of art.

Never truly sticking to one style of painting, Caillebotte aimed to depict modern life for what it really was in the realist sense. Nonetheless, an Impressionist influence is evident in his loose brushstrokes and “cropped” paintings.

Fun fact: On the ground floor of the center building in the background, there is a green “pharmacie” sign with yellow letters. Nowadays, the same building, located in between Rue de Moscou and Rue Clapeyron, still has a pharmacy.

0 Comments

Where?

What do you see? A young dancer of fourteen years old is shown at 70 percent of her real size (the sculpture is a bit taller than 3 foot or about 1 meter). She seems relaxed and is standing in ballet’s fourth position (there are seven positions for the feet in ballet, and the ballerina here has her feet in open fourth position – about 12 inches apart and facing different directions). The girl is sculpted realistically and Degas intends to show the hard life of a ballet dancer and what it does to her body. Her back leg supports most of her weight. She has thin legs and arms, holds her arms behind her back, and has her hands clasped together. She confidently holds up her chin, pushes her shoulders back, and her eyes are half closed. She wears ballet shoes, a real tutu made of tarlatan, and a gold-colored bodice (a vest) made of linen. The girl also wears a real ribbon in her plaited hair. Degas used real hair for this sculpture, which he covered in wax.

Copies: The National Gallery of Art holds two statues (the original wax statue and a bronze casting) of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen as well as two nude studies for this statue. When Degas died, about 150 statues were found in his studio of which only one of the versions in the National Gallery of Art had been shown to the public at an exhibition. Many of these statues were in bad shape, but about half of these statues were repaired after his death. The National Gallery of Art has many of these original statues.

The surviving family of Degas decided to create about 22 bronze casts of these statues. Because of this, nowadays, bronze copies of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen can be found in many other locations besides the ones mentioned on the top. For example, the statue is also in the the Art Institute of Chicago, Harvard Art Museums, Metropolitan Museum of Art (currently not on view), and the Norton Simon Museum. One of the bronze copies of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen was sold in 2009 for $19 million.

Who is Degas? Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas (1834-1917) was born in Paris. Whereas he spent most of his life in Paris, he also lived for three years in Italy and spent time in Florence, Naples, and Rome. He started as a more traditional painter by creating historical stories and portraits, but during the 1860s he changed his style and became one of the founders of Impressionism, together with artists like Cézanne, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, and Renoir.

Later on, he changed his focus and started to paint scenes from everyday life with a particular interest in dancers, theater, and horse racing. He moved on to focus on more realistic paintings, and one such example is Interior in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He made statues mainly as training to understand the anatomy and movements of people.

Fun fact: When Degas showed this sculpture at an Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1881, many people did not like it at all. For example, some people called the sculpture a monkey. It also did not help that the sculpture was on display in a glass vitrine. Sculptures typically were idealized versions of well-known people created in marble. Instead, Degas created an unknown young girl from Paris, and the girl did not look at all like a goddess. On top of that, he created this sculpture from beeswax and he added objects like a tutu to the statue. Because of the negative reactions Degas got, he removed the statue from the exhibition and stored it in his studio until his death.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Canvas or statue (Amazon links).

Where? Room 29 on the fifth floor of the Musée d’Orsay

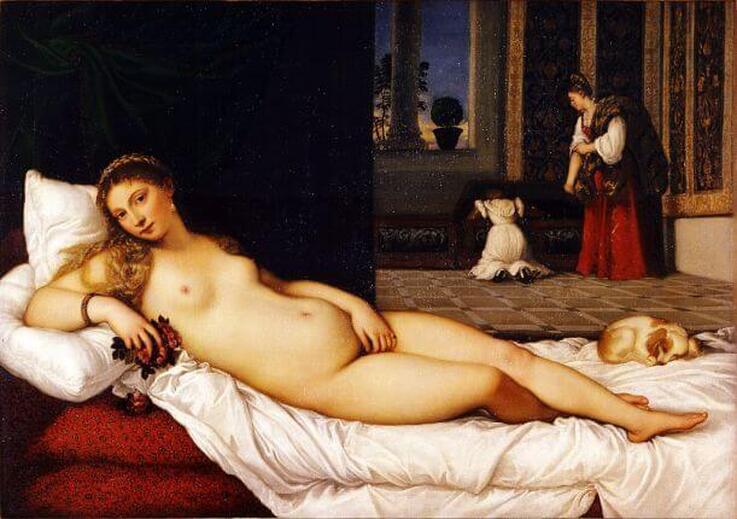

When? 1863 What do you see? Four figures picnicking on the grass. The two men are dressed in fashionable clothes of the 1860s. The man on the right gestures towards the man in the center who seems to be looking elsewhere. Sitting with them is a nude woman. She looks directly at the viewer with her hand on her chin. Her body is minimally shaded, making her appear flat to the canvas. In the lower left corner are the woman’s clothes and a basket of fruit and bread. Behind them, a woman dressed in white is wading in a small body of water. She seems to be reaching for something in the water. A black and orange bird flies over her. On the right is a wooden rowboat. Given her position in the background, this woman is painted larger than you would expect based on the laws of perspective; she isn’t much smaller than the figures in the foreground, creating a confusing sense of depth in the painting. Backstory: Also known as Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, the Luncheon on the Grass was inspired by two famous artworks: The Pastoral Concert by Giorgione and/or Titian in the Louvre and a drawing of the Judgement of Paris by Raphael (of which an engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art has survived). Despite his knowledge of the old masters, Manet’s work was completely avant-grade and shocking to the Parisian public. Firstly, it was considered offensive to depict a nude woman, especially if the woman was not a goddess or other mythological character. Manet depicts an average woman, breaking the tradition of idealized female nudes like the Venus of Urbino by Titian or The Birth of Venus by Botticelli. Placing her in a contemporary setting with two trendy Parisian men made for a very shocking and offensive scene. Secondly, Manet received a lot of criticism for his painting technique, which featured loose brushstrokes, a departure from the refined finish that can be seen in Renaissance paintings. Thirdly, his rendering of space in this painting is distorted as the woman in the water is abnormally large for her position in the background. For all these reasons, Luncheon on the Grass was rejected from the Paris Salon. Instead, it was exhibited at the Salon des Refusés in 1863. There, it was still received with ridicule and outrage for its subject matter and technique. People laughed at the painting and some even hit the painting with sticks. Critic Louis Etienne called it a “young man’s practical joke” and a “shameful open sore” in Le Jury et les Exposants.

Who is Édouard Manet? Édouard Manet was born in 1832 in Paris where he died 51 years later. Manet was a Parisian Realist painter who studied under Thomas Couture for six years. Afterward, however, he decided against attending the École des Beaux-Arts.

Early on in his career, he befriended Charles Baudelaire whose work featured urban outsiders such as prostitutes and street entertainers. Baudelaire’s writing inspired Manet to continue painting unusual characters alongside his other works that featured better-known figures such as musicians and writers. Manet’s avant-garde style that preceded Impressionism was often attacked by the press, but he was also defended by other creatives such as Emile Zola, Claude Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Among his famous paintings are Olympia in the Musée d’Orsay (and painted in the same year as the Luncheon on the Grass) and The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fun fact: The nude woman in Luncheon on the Grass is modeled after Victorine Meurent who also posed for Manet’s Olympia. She was a working class woman and aspiring painter whose work was actually exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1876. She and Manet had a close relationship, but her willingness to pose nude for his paintings tarnished her reputation. The men in the painting were modeled after Gustave Manet and Ferdinand Leenhoff, Manet’s brother and brother-in-law. respectively.

Where? Room 14 on the Ground floor of the Musée d’Orsay

When? 1863 What do you see? A Parisian prostitute, Olympia, lies down on her bed in her apartment. She rests atop a floral cloth, staring directly at the viewer as her servant presents her with a bouquet (perhaps a gift from an admirer or patron). Olympia’s left hand is firmly placed over her private area. She is pale, and her features are not idealized as was typically done by other artists at this time. Instead, Manet painted her realistically. Olympia’s body has dark outlines and broad color that lacks shading. She appears flat and stands in stark contrast to the dark brown and green background behind her. At her feet is a startled black cat with its tail raised. Backstory: Victorine Meurent served as the model for Olympia. She was a painter herself and served as a model for various artists. Manet liked her as a model because of her petite stature and red hair. Laure served as the model for the maid, and she posed for several other paintings of Manet. Édouard Manet got his inspiration for Olympia from the Venus of Urbino, the iconic Renaissance painting by Titian in the Uffizi Museum. Titian’s painting is a classic example of the female nude as a manifestation of ideal beauty. His reclining nude, like most, was shrouded in perfection and mythology. It was not inherently sexual. In his painting, Manet reduced the female nude to a much more realistic form. There is no beauty or goddess to admire; the viewer is confronted with Olympia’s sexuality as well as the reality of prostitution in Paris. And unlike the demure and reserved reclining nudes of the past, Manet’s modernized version features a woman who addresses the viewer and holds a firm posture.

Controversy: The painting caused quite an uproar when it was displayed in the Paris Salon in 1865. The French public was not ready to receive such a bold painting that deviated so strongly from what they were used to. Over seventy critics condemned the work for a variety of reasons and political cartoons mocking Olympia as ugly surfaced in newspapers and magazines.

The realistic style of this painting was not appreciated. Moreover, to show a sex worker as so bold and independent was very unconventional during the time. The idea that Olympia could live so comfortably (with flowers and jewelry) shook critics to the core. In addition, the painting breaks tradition by showing an imperfect female nude who stands in contrast to the flawless depictions of Venus from the past. Who is Olympia? In 1860s France, “Olympia” was an alias commonly used by prostitutes or courtesans. She is not of lower status as we would expect. Instead, she is shown to be of a higher class, adorned with jewelry and resting on a floral blanket with a servant at her side. Who is Manet? Édouard Manet was born in 1832 in Paris where he died 51 years later. He was a Parisian realist painter who studied in the studio of Thomas Couture for six years. Afterward, however, Manet decided against attending the official art school of the French Academy, the École des Beaux-Arts. Early on in his career, he befriended the poet Charles Baudelaire whose work featured urban outsiders such as prostitutes and street entertainers. Baudelaire’s writing inspired Manet to continue painting unusual characters alongside his other works that featured better-known figures such as musicians and writers. Manet also had a love for the sea and occasionally liked to capture this in this works, such as the Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. While most of Manet’s works can be classified under Realism, he is also one of the masterminds behind the development of Impressionism. The Rue Mosnier with Flags in the Getty Museum is a good example of his Impressionist ideas.

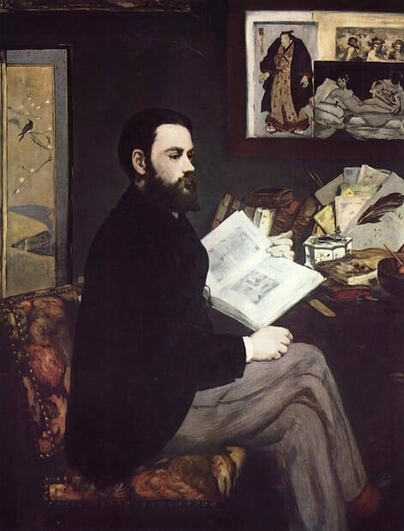

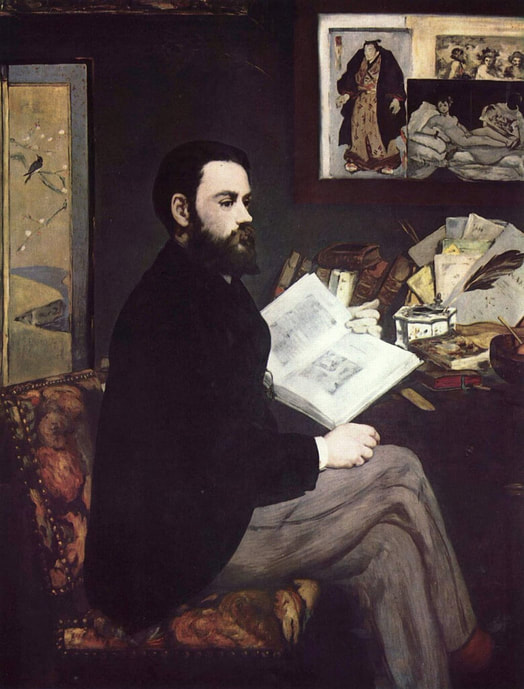

Fun fact: In 1867, Manet held a solo exhibition during the World’s Fair in Paris. Once again, Olympia was on display. When the painting received criticisms once again, writer Emile Zola defended it with a pamphlet that praised Manet’s bold style and technique. He asked viewers to overlook the subject matter and appreciate Manet’s avant-garde approach to art. As thanks, Manet produced the Portrait of Emile Zola. It features Zola in his study, reading some of his own works. In the upper right, Manet added a miniature print of Olympia to Zola’s wall.

Where? Room 14 of the Musée d’Orsay

When? 1868 What do you see? The 27-year old writer Émile Zola sits straight in a cushioned chair. He is fashionably dressed as a Parisian dandy, wearing a black jacket with grey pants. One hand rests on his knee, half-clenched. In his other hand, he holds Charles Blanc’s L’Histoire des Peintres, a book about art history. Zola seems to be in thought about something he has just read. The blankness of his expression makes the objects around him the subject of the viewer’s attention. In the background are artifacts from Japan, including an ink well on the desk, a painted screen on the far left, and a print of Utagawa Kuniaki’s Wrestler of Onaruto Nadaemon on the wall. The organized clutter atop his desk accentuates his wit and intellect. Among the books is a light blue pamphlet in which Zola defended Manet controversial painting Olympia. Directly above it is a print of Olympia herself. Behind it is a print of another famous painting, The Triumph of Bacchus by Diego Velázquez.

Backstory: In 1867, Manet had a solo exhibition. His best-known work, Olympia, was put on display for the second time. The work had received much criticism in 1865 for its avant-garde subject matter and “unrefined” style. Upon its second public display, the painting was once again the subject of many harsh comments.

Writer Émile Zola came to Manet’s defense and wrote an article in La Revue du XXe siècle. The article praised Manet’s bold style and technique, asking viewers to overlook the “risque” subject matter. Zola later published the article in its own brochure that sits on his desk in this portrait. As thanks, Manet painted Zola’s portrait. Over the course of several months, Zola posed extensively for the portrait in Manet’s studio. According to Zola, these sessions were long and exhausting as Manet did not engage in much conversation when he was painting. Manet’s main emphases in this portrait were Zola’s intellect and the aesthetics of the Far East. With the influx of Japanese goods into France in the mid-nineteenth century, many artists began imitating the flatness and simplicity of Japanese woodblock prints. This movement, known as Japonisme, was a precursor to Impressionism. Who is Émile Zola? A French writer who was born in 1840 in Paris. He is often credited as a founder of the naturalism movement in literature. He was childhood friends with Paul Cézanne who later introduced him to Manet. Zola was unemployed and lived in poverty for two years of his adult life. It was only when he published his first novel, Claude’s Confession that he was able to land a job as a journalist. Zola went on to write many more novels and published his best-known series, The Rougon Family Fortune. In the 1860s, Zola defended Impressionist artists like Cézanne, Manet, Renoir, and Monet. Who is Manet? Édouard Manet was born in 1832 in Paris where he died 51 years later. He was a Parisian Realist painter who studied in the studio of Thomas Couture for six years. Afterward, however, Manet decided against attending the official art school of the French Academy, the École des Beaux-Arts. Early on in his career, he befriended the poet Charles Baudelaire whose work featured urban outsiders such as prostitutes and street entertainers. Baudelaire’s writing inspired Manet to continue painting unusual characters alongside his other works that featured better-known figures such as musicians and writers. Manet was friends with Monet who he first considered to be a rival. He believed Monet to be copying his work. However, the pair made amends and eventually traveled to Argenteuil together. Many works came out of this trip, including Monet Painting in his Studio Boat.

Fun fact: Manet altered the print of Olympia in his portrait for Zola. Instead of facing the viewer, Olympia is looking at Émile Zola who had publicly defended her after this painting had received so much criticism at the Paris Salon (a very popular yearly art exhibition) of 1865.

Three years later, Manet submitted the painting to the Paris Salon of 1868 where it got accepted. The painting received mixed critical reviews. Some thought that the portrait was one of the best at the Salon of that year, while others thought the painting lacked animation and that it looked more like a still life than a portrait.

Where? Gallery 153 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

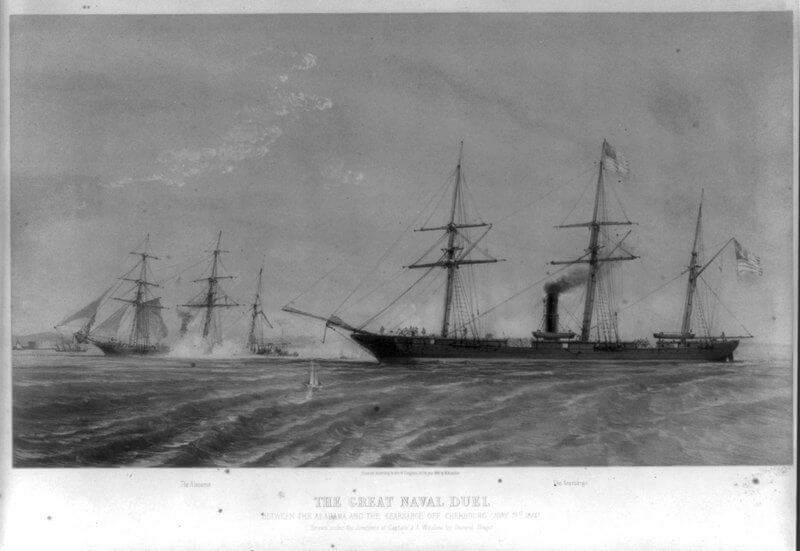

When? 1864 What do you see? Looking from a boat on the sea, we can see a green and blue rocky sea that makes up most of the painting. The large ship in the center background is the CSS Alabama. A lot of smoke is rising from the ship as the USS Kearsarge has just hit its engine. The rear of the ship is already sinking. Crew members of the ship are jumping into a small lifeboat in front of it. On the left side, behind the CSS Alabama, you can see part of the USS Kearsarge. We can see the U.S. flag on the top left, but most of the Kearsarge is hidden behind the smoke. The boat on the top right is the Deerhound. It is an English ship that is on its way to rescue some of the survivors on the CSS Alabama. It carries a red flag to indicate that it belongs to the British Royal Mersey Yacht Club. The small boat in the foreground is a French pilot boat, Les Deux Jeunes Soeurs, which is also on its way to rescue some of the survivors from the CSS Alabama. The boat has three flags: A French flag in the back, a regulation blue and white flag of pilot boats in the middle, and a white flag in the front to indicate that it is neutral in this conflict. It also carries a small boat to rescue more people. To the right of this ship is a mast in the water with a surviving sailor holding on. Backstory: During the American Civil war, the Confederate States had no navy to defend themselves against the Union States. The Union States blocked the export of cotton by ship from the Confederate States, and so the Confederate States decided to buy a series of warships from England. The CSS Alabama was a ship of the Confederates and was built in 1862. In its first two years, it had already sunk 65 ships of the Unionists throughout the world. On June 11, 1864, the ship anchored at the entrance of the harbor of Cherbourg, in the North of France. On June 19, 1864, the CSS Alabama got into a fight with a warship of the Union States, the USS Kearsarge. While the CSS Alabama had heavier firepower, the USS Kearsarge was a more advanced ship with more precise firepower. Thousands of French spectators witnessed the fight between the two ships from the coast, and the USS Kearsarge defeated the CSS Alabama, which sank. The fight was widely covered in the newspapers, as can be seen by the illustration below in the Illustrated London News.

The American Civil War: The American Civil War took place between 1861 and 1865 in the United States during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln. It was a war between the Confederate States, representing the Southern states of the U.S., and the Union, representing the other U.S. states. The Confederate States were supporting slavery, while the Union States followed the U.S. Constitution and were against slavery. The Union States won the war, and the slaves in the South were freed. About 700,000 people died during this war.

Who is Manet? Édouard Manet was born in 1832 in Paris and died there in 1883. When Manet was 18 years old, he spent about one year on a ship going to Brazil. While he failed the examination for the naval academy, he remained always fascinated by the sea. About ten percent of his paintings were about the sea, including Rochefort’s Escape in the Kunsthaus Zurich. Manet is also the principal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism. During the 1860s, he became friends with painters such as Cézanne, Degas, Monet, Pissarro, and Renoir, and under the lead of Manet, they developed the Impressionist art style. An example of an Impressionist painting by Manet from 1878 is The Rue Mosnier with Flags in the Getty Museum.

Fun fact: Manet did not witness the fight himself. He learned about it from the newspapers which were full of information and drawings about this fight. Within 26 days of this fight, this painting by Manet was already exhibited.

It is likely that Manet did not know the details about the USS Kearsarge and that this was the reason that he hid a large part of that ship behind the smoke. He only saw the USS Kearsarge after he finished this painting and in another painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, entitled The Kearsarge at Boulogne, he depicted this ship. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas.

Where? Gallery 153 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

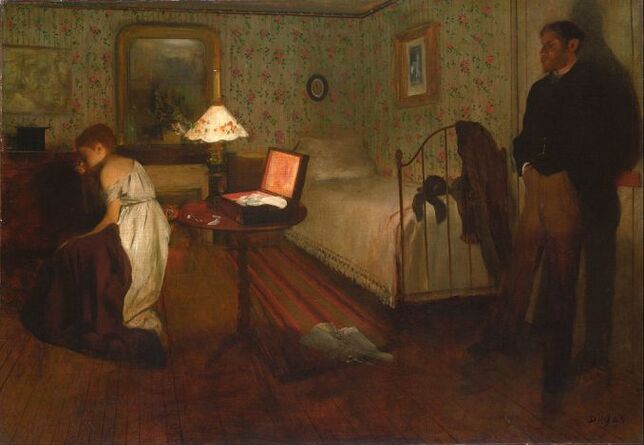

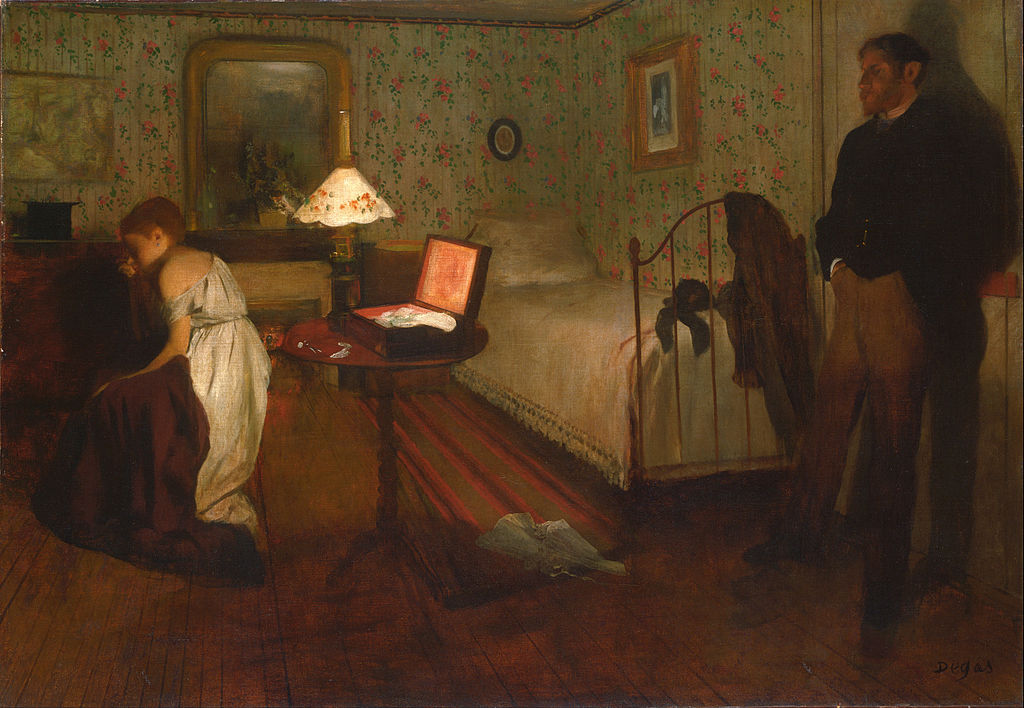

When? 1868-1869 What do you see? Two people are shown in a bedroom. On the right is a man standing against the door with his legs wide and his hands in his pocket. He is standing in the darker part of the room, and you can see his large shadow on the door. On the left, is a woman kneeling down. She is partially undressed, and the lamp behind her lights her white dress. The woman is facing away from the man, and she may be crying. Behind the woman is a round table with a lamp on it and a sewing box with a piece of clothing inside. On the floor lays a white corset. The single bed is neatly made up with the woman’s hat and a cloak at the foot end. The wall is decorated with wallpaper with pink flowers on it. In the background is a fireplace and above it hangs a mirror. On the left, you can see the top hat of the man on top of a closet. Above the top hat hangs a map on the wall.

Backstory: After painting this work, the painting remained in the studio of Degas for 36 years, until he put it up for sale in 1905. Before that, only a few friends of Degas had seen this painting. The interpretation of this painting is open to quite some debate and this uncertainty adds to the appeal of the painting.

Degas captures a specific moment in time, with little indication of the past and future, making it harder to interpret the painting. Degas did this more often early in his career, for example, in the Women Ironing in the Norton Simon Museum. It is likely that Degas kept the meaning of Interior vague on purpose. All he ever mentioned about this work was that it was a genre painting with the title ‘Interior’. Especially during the period in which this he created this work, Degas wanted to challenge existing norms and may, therefore, have enjoyed creating a painting with an ambiguous interpretation.

Interpretation: One of the earlier interpretations of this painting is about rape, and that is why this painting is also known as ‘The Rape’. According to this interpretation, the girl is a worker and the man is her boss. The girl has just been raped and is crying, while the man is standing against the door overthinking his deed and showing some remorse (some say that there are traces of blood on the bed which would support this interpretation). However, this interpretation is not accepted by many.

Over time, art historians have searched for various literary sources that could have inspired this painting. And while some literary sources match some aspects of the painting, none of them are truly consistent with this painting. One of the most convincing of these interpretations is that this painting depicts the wedding night for the couple in the room. However, one year before the wedding they have murdered the former husband of the woman, and in this painting, they are overwhelmed by the feeling of how bad that was. Who is Degas? Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas (1834-1917), better known as Edgar Degas, was born in Paris. He was both a painter and a sculptor and more than half of his works are related to dance. One such example is The Ballet Class in the Musée d’Orsay, and another is his statue of The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer in the National Gallery of Art. Together with painters like Cézanne, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, and Renoir, he is one of the founders of impressionism. His works often have some complex psychological meaning. Later in his career, he became a specialists in depicting movement in his works. He learned painting at an early age, and when he was 21, he met Ingres, who stimulated him to pursue an artistic career. He started by copying some details of the works of some famous Renaissance painters, like Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian, but gradually developed his own style. At the beginning of his career, he was an Impressionist, but his style evolved into Realism. He was also an art collector and was particularly fond of the works of Daumier, Delacroix, and Ingres.

Fun fact: One of the hobbies that Degas developed in the 1880s was photography. He made and collected photos which he used as inspirations for his paintings. While photography was only invented at the beginning of the 19th century, Degas already used a ‘photographic’ style in some of his earlier work.

His Interior painting, for example, is comparable to a photograph, as he captures a single moment in time and does not include many clues on what happened before and after the picture. As discussed, this leaves the interpretation of the painting open for discussion. It is therefore not surprising that Degas later got very interested in photography. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us