|

Where? Room W204 of the J. Paul Getty Museum

When? 1878 What do you see? A street full of French flags on the day that the French people celebrated the fête de la Republique. This work is painted during the afternoon of June 30, 1878. Several well-dressed people walk through the street, and we can see some horse-drawn carriages as well. On the lower left is a man with one leg. He hunches and wears a blue cape. He is dressed as a laborer and is probably a war veteran. Behind the laborer is a ladder, and to his left is half of a railroad track. To the left of this track is a wooden fence, behind which are the leftovers of a building that had collapsed. On that spot, a new train station was built, the Gare Saint-Lazare. Backstory: This national holiday was celebrated enthusiastically throughout Paris. However, Manet did not depict the most representative scene from that day. The Rue Mosnier was not a very big street and certainly not the street where the wildest celebrations for the national holiday took place. Nowadays, the street is called the Rue de Berne. Manet painted this work in front of a second-floor window in his studio overlooking the Rue Mosnier. The Getty Museum acquired this painting in 1989 for $26.4 million, which was the highest price paid for a Manet painting at that time. Other versions: Manet painted this street two more times. Both versions are in a private collection. One version, Rue Mosnier with Pavers, shows the street on a normal day when the street is paved. Manet painted the other version, Rue Mosnier Decorated with Flags, earlier on the day on June 30, 1878. This version is a more festive, but less refined depiction of the celebrations.

Moral message: Manet shows the contrast between the celebration of the National Day of France and the consequences of the Franco-Prussian war in 1870-1871 (a war between France and Germany). The well-dressed people, horse carriages, and flags show the prosperous side of France which can be celebrated. In addition, this celebration is in honor of the successful World Expo that took place in Paris.

In contrast, the one-legged man on the bottom left is probably a war veteran who lost his leg in the war earlier that decade. The leftovers of the railroad track and the collapsed building on the left, represent the war consequences. Manet illustrates that while some people can be happy with their country, others still suffer the consequences of the turbulent past and there is still much work necessary to build up the country.

As a young painter, Manet was influenced by the works of Frans Hals and Diego Velázquez. However, he developed his own painting style and became one of the founders of Impressionism. This painting is a good example of his Impressionist work. His innovative works have had a big impact on the development of future painting styles.

Fun fact: Manet originally created a picture of the disabled man in the bottom left for a music album to be published in 1878. Manet made a drawing of a disabled man, owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for a music album, Les Mendiants. The album, created by the unconventional musician Cabaner, is based on poems from a book, La Chansons de Gueux, by Jean Richepin. Beggars, prostitutes, and other outcasts formed the theme of the album.

One of the poems specifically dealt with a disabled man who was begging outside a church. In the end, the album was never released, and Manet could thus use the image of the disabled man for this painting. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster.

0 Comments

Where? Gallery 225 of the Art Institute of Chicago

When? 1864 What do you see? The sea as seen from Boulogne-sur-Mer, a French beach town on the English Channel, about 60 miles (100 km) South of the border between Belgium and France. Compared to seascapes by earlier artists, Manet used a high horizon line in his paintings, such that the biggest part of this painting is made up by the sea and the ships. Among the numerous sailboats is a steamboat which pollutes the view and the sky with its dark smoke. The steamboat is leaving from France to England through the English Channel. It leaves a visible trace in the water showing that it has to navigate its way through the asymmetrically scattered sailboats. Manet uses broad, horizontal brush strokes to paint the sea. Moreover, he uses blue and green pigments for the sea, and in some places, traces of the white canvas are still visible. These relatively bright colors make the sea the focus of the painting. The sea appears flat and calm, and this painting is the most abstract of the seascapes that Manet painted. Backstory: In July 1864, Édouard Manet went with his extended family on a vacation to a seaside resort in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. It was not just a vacation for Manet because he brought his brushes and easel and created several paintings of the sea and the ships. It was one of the first times that he worked on paintings outside, though he finished the painting in his studio in Paris. In this painting, he depicts an ugly steamboat among the more graceful sailboats. The first steamboats were developed by the end of the 18th century, and they were an important development as they could carry passengers and freight over large distances. In addition, they were an important innovation for the Navy, and they played an important role in the American Civil War. Seascapes: Sometimes referred to as Marine Art, the primary theme of the seascape is the sea. Its popularity has come in waves. For example, during the 17th century, seascapes were popular among Dutch artists. During the Dutch Golden Century, artists from The Netherlands painted scenes of sea battles. These paintings were very detailed and showed all the ongoing action of these battles. Seascapes became popular again among painters in the 19th century, especially after train connections between Paris and the French beaches were established around 1850. Besides Manet, painters like Courbet, Monet, Renoir, and Whistler created beautiful seascapes. However, J. M. W. Turner had already popularized the theme in the early 19th century. An example of a seascape painting by Turner is The Fighting Temeraire in the National Gallery in London, which he painted in 1838. Almost three decades later, Manet also started to paint several seascapes. One of his more popular seascapes is his 1864 painting of the Battle of Kearsarge and the Alabama in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The big difference between the 19th-century and 17th-century seascapes is that during the 19th century many details were left out of the paintings and the focus became the composition instead.

Who is Manet? Édouard Manet (1833 – 1883) was a French painter from Paris, France. He painted Steamboat Leaving Boulogne relatively early in his career. Manet’s paintings during that period were unconventional and were not well-received by art critics and the public. The Paris Salon, the biggest art exhibition in the world during the 19th century, rejected most of his works.

Manet also only sold few works and did not receive commissions. However, he persisted in his new style of painting during his career, relying on the financial support of his mother. Nowadays, his works are very popular. A good example is The Rue Mosnier with Flags from 1878 which was acquired by the Getty Museum in 1989 for $26.4 million.

Fun fact: Manet had always been fascinated by the sea. Following the suggestion of his father, he joined a training vessel for a three-month trip to Rio de Janeiro when he was 16 years old. He liked this experience and when he returned in 1849, he attempted the entrance exam to the Navy. However, he failed the entrance exam twice and decided that he wanted to become a painter instead – which was his first love – much to the dislike of his father.

Art lovers nowadays are happy that he became a painter instead. Not only are his works highly admired today, he also has had a major influence on the development of Impressionism, which has become one of the most popular painting styles ever developed. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas

Where? Room 29 on the fifth floor of the Musée d’Orsay

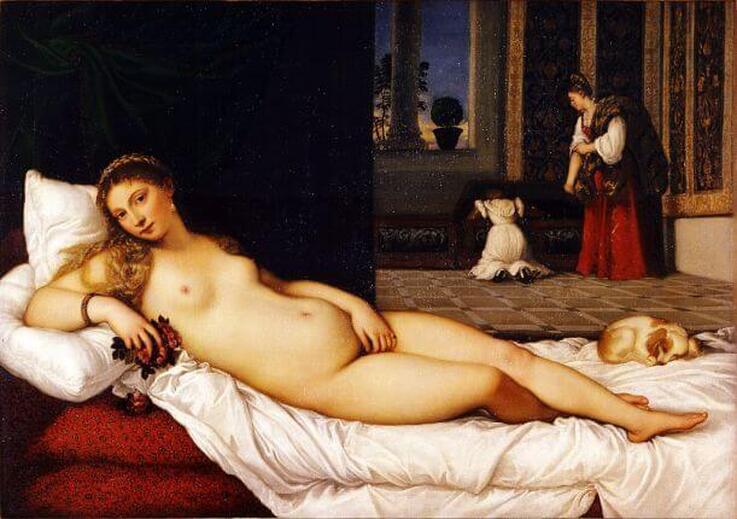

When? 1863 What do you see? Four figures picnicking on the grass. The two men are dressed in fashionable clothes of the 1860s. The man on the right gestures towards the man in the center who seems to be looking elsewhere. Sitting with them is a nude woman. She looks directly at the viewer with her hand on her chin. Her body is minimally shaded, making her appear flat to the canvas. In the lower left corner are the woman’s clothes and a basket of fruit and bread. Behind them, a woman dressed in white is wading in a small body of water. She seems to be reaching for something in the water. A black and orange bird flies over her. On the right is a wooden rowboat. Given her position in the background, this woman is painted larger than you would expect based on the laws of perspective; she isn’t much smaller than the figures in the foreground, creating a confusing sense of depth in the painting. Backstory: Also known as Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, the Luncheon on the Grass was inspired by two famous artworks: The Pastoral Concert by Giorgione and/or Titian in the Louvre and a drawing of the Judgement of Paris by Raphael (of which an engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art has survived). Despite his knowledge of the old masters, Manet’s work was completely avant-grade and shocking to the Parisian public. Firstly, it was considered offensive to depict a nude woman, especially if the woman was not a goddess or other mythological character. Manet depicts an average woman, breaking the tradition of idealized female nudes like the Venus of Urbino by Titian or The Birth of Venus by Botticelli. Placing her in a contemporary setting with two trendy Parisian men made for a very shocking and offensive scene. Secondly, Manet received a lot of criticism for his painting technique, which featured loose brushstrokes, a departure from the refined finish that can be seen in Renaissance paintings. Thirdly, his rendering of space in this painting is distorted as the woman in the water is abnormally large for her position in the background. For all these reasons, Luncheon on the Grass was rejected from the Paris Salon. Instead, it was exhibited at the Salon des Refusés in 1863. There, it was still received with ridicule and outrage for its subject matter and technique. People laughed at the painting and some even hit the painting with sticks. Critic Louis Etienne called it a “young man’s practical joke” and a “shameful open sore” in Le Jury et les Exposants.

Who is Édouard Manet? Édouard Manet was born in 1832 in Paris where he died 51 years later. Manet was a Parisian Realist painter who studied under Thomas Couture for six years. Afterward, however, he decided against attending the École des Beaux-Arts.

Early on in his career, he befriended Charles Baudelaire whose work featured urban outsiders such as prostitutes and street entertainers. Baudelaire’s writing inspired Manet to continue painting unusual characters alongside his other works that featured better-known figures such as musicians and writers. Manet’s avant-garde style that preceded Impressionism was often attacked by the press, but he was also defended by other creatives such as Emile Zola, Claude Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Among his famous paintings are Olympia in the Musée d’Orsay (and painted in the same year as the Luncheon on the Grass) and The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fun fact: The nude woman in Luncheon on the Grass is modeled after Victorine Meurent who also posed for Manet’s Olympia. She was a working class woman and aspiring painter whose work was actually exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1876. She and Manet had a close relationship, but her willingness to pose nude for his paintings tarnished her reputation. The men in the painting were modeled after Gustave Manet and Ferdinand Leenhoff, Manet’s brother and brother-in-law. respectively.

Where? Room 14 on the Ground floor of the Musée d’Orsay

When? 1863 What do you see? A Parisian prostitute, Olympia, lies down on her bed in her apartment. She rests atop a floral cloth, staring directly at the viewer as her servant presents her with a bouquet (perhaps a gift from an admirer or patron). Olympia’s left hand is firmly placed over her private area. She is pale, and her features are not idealized as was typically done by other artists at this time. Instead, Manet painted her realistically. Olympia’s body has dark outlines and broad color that lacks shading. She appears flat and stands in stark contrast to the dark brown and green background behind her. At her feet is a startled black cat with its tail raised. Backstory: Victorine Meurent served as the model for Olympia. She was a painter herself and served as a model for various artists. Manet liked her as a model because of her petite stature and red hair. Laure served as the model for the maid, and she posed for several other paintings of Manet. Édouard Manet got his inspiration for Olympia from the Venus of Urbino, the iconic Renaissance painting by Titian in the Uffizi Museum. Titian’s painting is a classic example of the female nude as a manifestation of ideal beauty. His reclining nude, like most, was shrouded in perfection and mythology. It was not inherently sexual. In his painting, Manet reduced the female nude to a much more realistic form. There is no beauty or goddess to admire; the viewer is confronted with Olympia’s sexuality as well as the reality of prostitution in Paris. And unlike the demure and reserved reclining nudes of the past, Manet’s modernized version features a woman who addresses the viewer and holds a firm posture.

Controversy: The painting caused quite an uproar when it was displayed in the Paris Salon in 1865. The French public was not ready to receive such a bold painting that deviated so strongly from what they were used to. Over seventy critics condemned the work for a variety of reasons and political cartoons mocking Olympia as ugly surfaced in newspapers and magazines.

The realistic style of this painting was not appreciated. Moreover, to show a sex worker as so bold and independent was very unconventional during the time. The idea that Olympia could live so comfortably (with flowers and jewelry) shook critics to the core. In addition, the painting breaks tradition by showing an imperfect female nude who stands in contrast to the flawless depictions of Venus from the past. Who is Olympia? In 1860s France, “Olympia” was an alias commonly used by prostitutes or courtesans. She is not of lower status as we would expect. Instead, she is shown to be of a higher class, adorned with jewelry and resting on a floral blanket with a servant at her side. Who is Manet? Édouard Manet was born in 1832 in Paris where he died 51 years later. He was a Parisian realist painter who studied in the studio of Thomas Couture for six years. Afterward, however, Manet decided against attending the official art school of the French Academy, the École des Beaux-Arts. Early on in his career, he befriended the poet Charles Baudelaire whose work featured urban outsiders such as prostitutes and street entertainers. Baudelaire’s writing inspired Manet to continue painting unusual characters alongside his other works that featured better-known figures such as musicians and writers. Manet also had a love for the sea and occasionally liked to capture this in this works, such as the Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. While most of Manet’s works can be classified under Realism, he is also one of the masterminds behind the development of Impressionism. The Rue Mosnier with Flags in the Getty Museum is a good example of his Impressionist ideas.

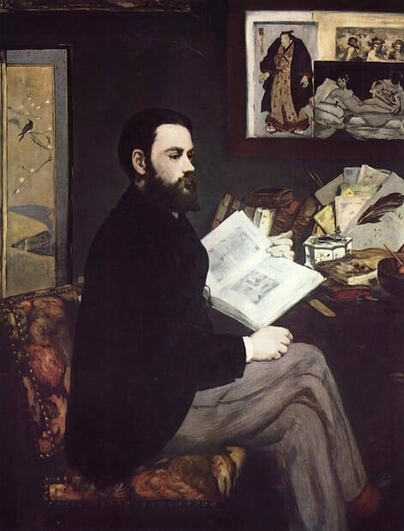

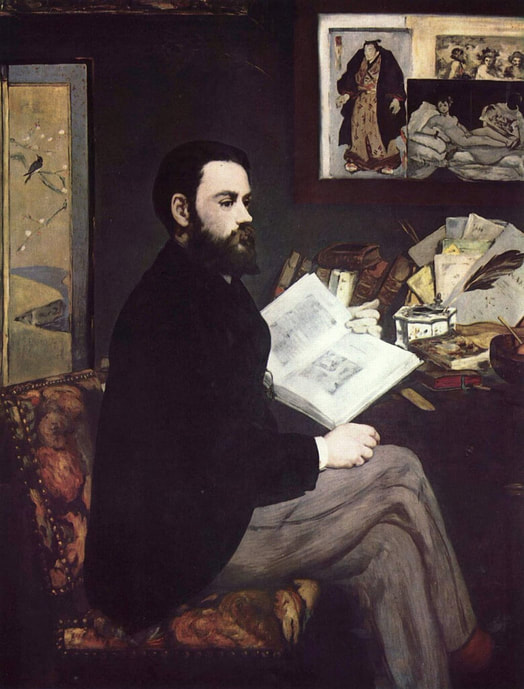

Fun fact: In 1867, Manet held a solo exhibition during the World’s Fair in Paris. Once again, Olympia was on display. When the painting received criticisms once again, writer Emile Zola defended it with a pamphlet that praised Manet’s bold style and technique. He asked viewers to overlook the subject matter and appreciate Manet’s avant-garde approach to art. As thanks, Manet produced the Portrait of Emile Zola. It features Zola in his study, reading some of his own works. In the upper right, Manet added a miniature print of Olympia to Zola’s wall.

Where? Room 14 of the Musée d’Orsay

When? 1868 What do you see? The 27-year old writer Émile Zola sits straight in a cushioned chair. He is fashionably dressed as a Parisian dandy, wearing a black jacket with grey pants. One hand rests on his knee, half-clenched. In his other hand, he holds Charles Blanc’s L’Histoire des Peintres, a book about art history. Zola seems to be in thought about something he has just read. The blankness of his expression makes the objects around him the subject of the viewer’s attention. In the background are artifacts from Japan, including an ink well on the desk, a painted screen on the far left, and a print of Utagawa Kuniaki’s Wrestler of Onaruto Nadaemon on the wall. The organized clutter atop his desk accentuates his wit and intellect. Among the books is a light blue pamphlet in which Zola defended Manet controversial painting Olympia. Directly above it is a print of Olympia herself. Behind it is a print of another famous painting, The Triumph of Bacchus by Diego Velázquez.

Backstory: In 1867, Manet had a solo exhibition. His best-known work, Olympia, was put on display for the second time. The work had received much criticism in 1865 for its avant-garde subject matter and “unrefined” style. Upon its second public display, the painting was once again the subject of many harsh comments.

Writer Émile Zola came to Manet’s defense and wrote an article in La Revue du XXe siècle. The article praised Manet’s bold style and technique, asking viewers to overlook the “risque” subject matter. Zola later published the article in its own brochure that sits on his desk in this portrait. As thanks, Manet painted Zola’s portrait. Over the course of several months, Zola posed extensively for the portrait in Manet’s studio. According to Zola, these sessions were long and exhausting as Manet did not engage in much conversation when he was painting. Manet’s main emphases in this portrait were Zola’s intellect and the aesthetics of the Far East. With the influx of Japanese goods into France in the mid-nineteenth century, many artists began imitating the flatness and simplicity of Japanese woodblock prints. This movement, known as Japonisme, was a precursor to Impressionism. Who is Émile Zola? A French writer who was born in 1840 in Paris. He is often credited as a founder of the naturalism movement in literature. He was childhood friends with Paul Cézanne who later introduced him to Manet. Zola was unemployed and lived in poverty for two years of his adult life. It was only when he published his first novel, Claude’s Confession that he was able to land a job as a journalist. Zola went on to write many more novels and published his best-known series, The Rougon Family Fortune. In the 1860s, Zola defended Impressionist artists like Cézanne, Manet, Renoir, and Monet. Who is Manet? Édouard Manet was born in 1832 in Paris where he died 51 years later. He was a Parisian Realist painter who studied in the studio of Thomas Couture for six years. Afterward, however, Manet decided against attending the official art school of the French Academy, the École des Beaux-Arts. Early on in his career, he befriended the poet Charles Baudelaire whose work featured urban outsiders such as prostitutes and street entertainers. Baudelaire’s writing inspired Manet to continue painting unusual characters alongside his other works that featured better-known figures such as musicians and writers. Manet was friends with Monet who he first considered to be a rival. He believed Monet to be copying his work. However, the pair made amends and eventually traveled to Argenteuil together. Many works came out of this trip, including Monet Painting in his Studio Boat.

Fun fact: Manet altered the print of Olympia in his portrait for Zola. Instead of facing the viewer, Olympia is looking at Émile Zola who had publicly defended her after this painting had received so much criticism at the Paris Salon (a very popular yearly art exhibition) of 1865.

Three years later, Manet submitted the painting to the Paris Salon of 1868 where it got accepted. The painting received mixed critical reviews. Some thought that the portrait was one of the best at the Salon of that year, while others thought the painting lacked animation and that it looked more like a still life than a portrait.

Where? Gallery 153 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

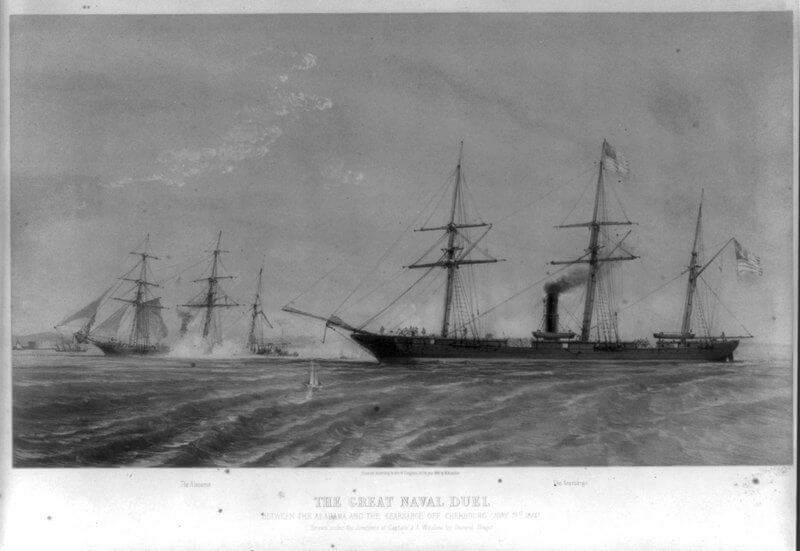

When? 1864 What do you see? Looking from a boat on the sea, we can see a green and blue rocky sea that makes up most of the painting. The large ship in the center background is the CSS Alabama. A lot of smoke is rising from the ship as the USS Kearsarge has just hit its engine. The rear of the ship is already sinking. Crew members of the ship are jumping into a small lifeboat in front of it. On the left side, behind the CSS Alabama, you can see part of the USS Kearsarge. We can see the U.S. flag on the top left, but most of the Kearsarge is hidden behind the smoke. The boat on the top right is the Deerhound. It is an English ship that is on its way to rescue some of the survivors on the CSS Alabama. It carries a red flag to indicate that it belongs to the British Royal Mersey Yacht Club. The small boat in the foreground is a French pilot boat, Les Deux Jeunes Soeurs, which is also on its way to rescue some of the survivors from the CSS Alabama. The boat has three flags: A French flag in the back, a regulation blue and white flag of pilot boats in the middle, and a white flag in the front to indicate that it is neutral in this conflict. It also carries a small boat to rescue more people. To the right of this ship is a mast in the water with a surviving sailor holding on. Backstory: During the American Civil war, the Confederate States had no navy to defend themselves against the Union States. The Union States blocked the export of cotton by ship from the Confederate States, and so the Confederate States decided to buy a series of warships from England. The CSS Alabama was a ship of the Confederates and was built in 1862. In its first two years, it had already sunk 65 ships of the Unionists throughout the world. On June 11, 1864, the ship anchored at the entrance of the harbor of Cherbourg, in the North of France. On June 19, 1864, the CSS Alabama got into a fight with a warship of the Union States, the USS Kearsarge. While the CSS Alabama had heavier firepower, the USS Kearsarge was a more advanced ship with more precise firepower. Thousands of French spectators witnessed the fight between the two ships from the coast, and the USS Kearsarge defeated the CSS Alabama, which sank. The fight was widely covered in the newspapers, as can be seen by the illustration below in the Illustrated London News.

The American Civil War: The American Civil War took place between 1861 and 1865 in the United States during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln. It was a war between the Confederate States, representing the Southern states of the U.S., and the Union, representing the other U.S. states. The Confederate States were supporting slavery, while the Union States followed the U.S. Constitution and were against slavery. The Union States won the war, and the slaves in the South were freed. About 700,000 people died during this war.

Who is Manet? Édouard Manet was born in 1832 in Paris and died there in 1883. When Manet was 18 years old, he spent about one year on a ship going to Brazil. While he failed the examination for the naval academy, he remained always fascinated by the sea. About ten percent of his paintings were about the sea, including Rochefort’s Escape in the Kunsthaus Zurich. Manet is also the principal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism. During the 1860s, he became friends with painters such as Cézanne, Degas, Monet, Pissarro, and Renoir, and under the lead of Manet, they developed the Impressionist art style. An example of an Impressionist painting by Manet from 1878 is The Rue Mosnier with Flags in the Getty Museum.

Fun fact: Manet did not witness the fight himself. He learned about it from the newspapers which were full of information and drawings about this fight. Within 26 days of this fight, this painting by Manet was already exhibited.

It is likely that Manet did not know the details about the USS Kearsarge and that this was the reason that he hid a large part of that ship behind the smoke. He only saw the USS Kearsarge after he finished this painting and in another painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, entitled The Kearsarge at Boulogne, he depicted this ship. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us