|

Where: British Museum Collection of 91 drawings by Maria Sibylla Merian, London, England

When: 1705–1706 from her trip to Suriname, South America What: Watercolor and bodycolor on vellum 36.8 x 24.9 cm What do you see? The image above shows plate 55 from an album of ninety-one drawings entitled Merian's Drawings of Surinam Insects (Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium) from 1705. The plant bears leaves, a flower, bud growth, and the growing green, yellow, and red peppers. Merian shows the stages of development of the peppers from several angles so the viewer sees the peppers' top, bottom, sides, and body. This plant is nutritious and supports the lifecycle of the moth. There are some errors in this volume of her work. It is believed that some of her samples got mixed up on the trip back to Holland from Suriname and were mislabeled on her return home. This insect was identified as a butterfly but is now classified as a moth. The Royal Collection Trust specifically called it a Carolina Sphinx Moth. Each of these plates is individually drawn and printed, demonstrating their differences. The printed versions show many more differences in colors and shadings, while others produce reverse printing. The yellow pepper on the right is split to reveal the eggs laid by the moth. The eggs will become larvae or caterpillars, which we can see on the leaf near the bottom. It will weave itself into a chrysalis (the correct term for moths and butterflies) or pupa with other insects, as seen on the green pepper on the left. The chrysalis is protected by an outer layer called the cocoon. The chrysalis transforms to produce a new insect that will emerge from the cocoon as a new moth, and the cycle repeats.

0 Comments

Where? Gallery 201 at The Art Institute of Chicago

When? 1877 What do you see? A busy, rainy street near the Saint-Lazare station in Paris. The canvas is divided in half by an axis, a tall green streetlamp. Walking on the right of it, in the foreground, are a couple dressed in the latest Parisian fashion. As they walk arm in arm beneath an umbrella, looking off to the left side of the canvas, a stranger passes them with his back to the viewer. Judging by the young woman’s brown dress and diamond earring, the pair are likely of the upper class. The men in the middle ground appear to be dressed in a similar fashion. Further down the canvas are some traces of the working class. Behind the man’s umbrella, a painter dressed in white carries a ladder across the street. Behind the woman, a baker looks out her window. Two carriage drivers can be seen on the left side of the street lamp.

Backstory: Exhibited at the Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877, Paris Street; Rainy Day was celebrated by many. The natural scene of a real Parisian street painted in a realistic fashion calls back to Caillebotte’s interest in photography. However, the painting’s style cannot be characterized as entirely realist or academic.

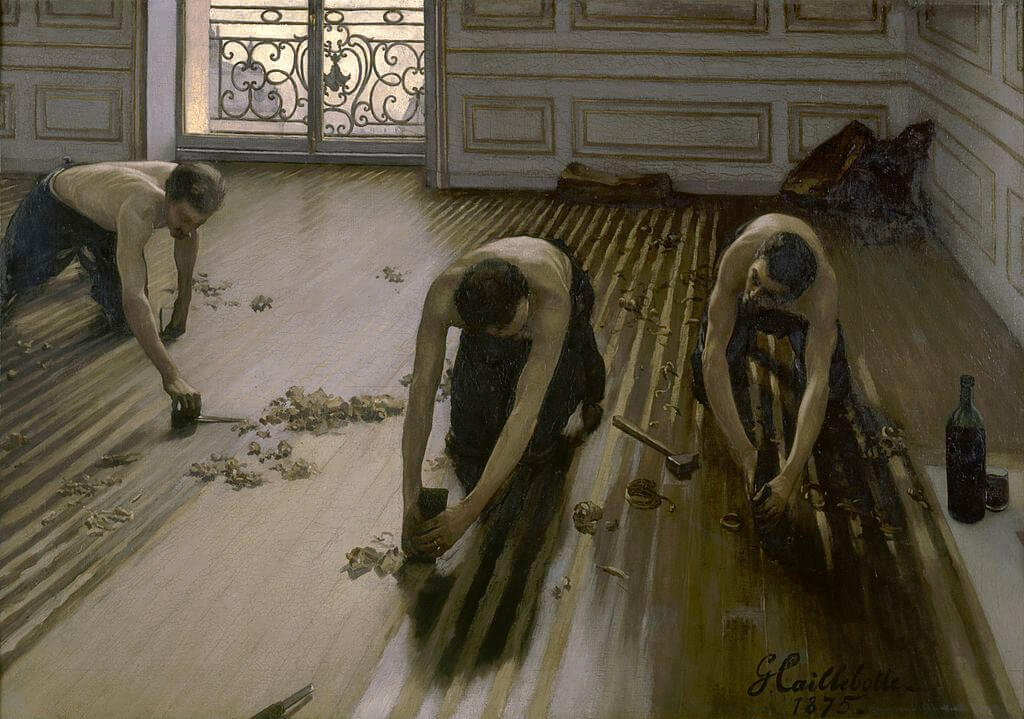

Caillebotte features an unusual asymmetrical composition and cropped figures. On the right side of the canvas, the man and woman’s legs are out of frame and the stranger with his back to the viewer is split in half. This detail may be overlooked by modern viewers but was considered radical by Caillebotte’s contemporaries. The cropped composition may have been inspired by his interest in photography. Featuring unsaturated colors and dim light, the painting has a gloomy and slow feeling. Subtly showing the division between the bourgeoisie and the working class, Caillebotte’s palette suits the daunting disparity that is most heavily felt by the workers. Who is Caillebotte? Gustave Caillebotte was born in 1848 in Paris and died in Gennevillers in 1894. He grew up in a wealthy family and began painting in the studio of Leon Bonnat. In 1873, Caillebotte began his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts and shortly after became acquainted with Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet. With his money, he was able to support many artists like Edgar Degas, Camille Pissaro, and Alfred Sisley. Although he did not participate in the first one, Caillebotte exhibited eight paintings in the Second Impressionist Exhibition of 1876, one of which was The Floor Scrapers in the Musée d’Orsay. Caillebotte’s academic style combined with an Impressionist influence produced a unique and modern style of art.

Never truly sticking to one style of painting, Caillebotte aimed to depict modern life for what it really was in the realist sense. Nonetheless, an Impressionist influence is evident in his loose brushstrokes and “cropped” paintings.

Fun fact: On the ground floor of the center building in the background, there is a green “pharmacie” sign with yellow letters. Nowadays, the same building, located in between Rue de Moscou and Rue Clapeyron, still has a pharmacy.

Where? Gallery 243 of The Art Institute of Chicago

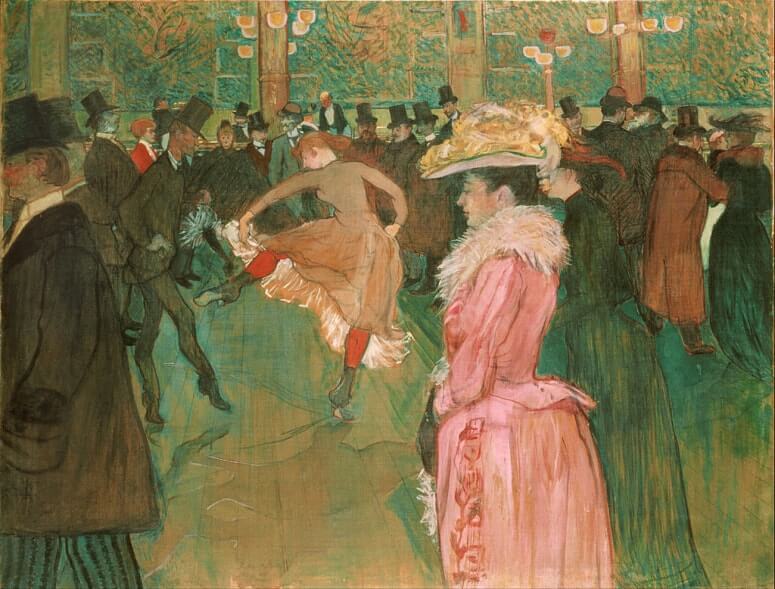

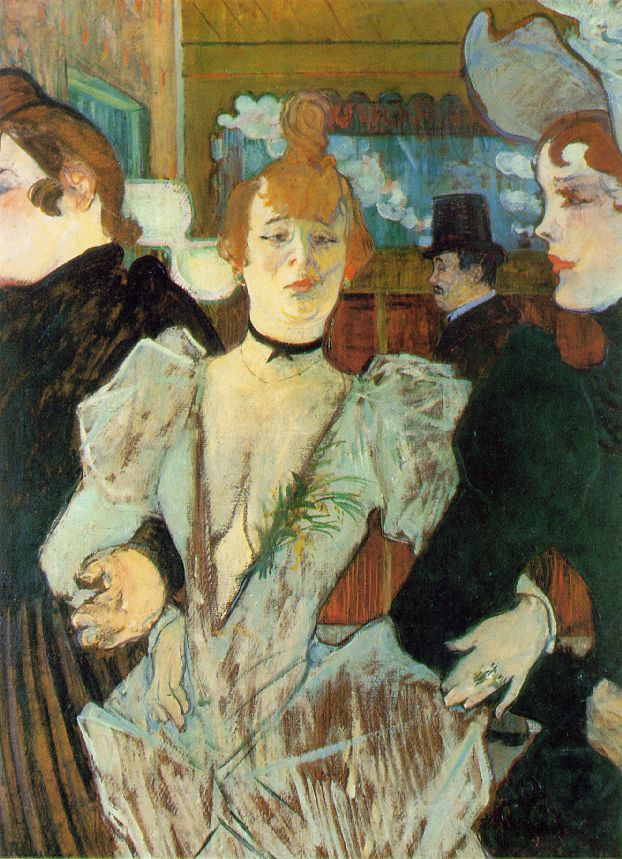

When? 1892-1895 What do you see? Behind a balustrade in one of the most popular nightclubs in Paris, three men and two women sit at a table, leaning into conversation. There are drinks on the table and each member of the party wears a fancy hat. The woman with orange hair is Jane Avril, a famous entertainer. Behind their table, one tall and one short man are passing by. In the right background, two women stand by a green mirror. The one fixing her hair is dancer La Goulue. Looking deeper into the room, there are many more guests sitting at tables with yellow lights hanging above them. Such a light may hang above the dancer May Milton in the left foreground. She stares at us with her bright teal skin, and her features have become grotesque and distorted under the harsh nightclub lights. Backstory: In the risky neighborhood of Montmartre, Paris, nightlife flourished through the end of the 19th century. People of various classes came to the nightclubs and dance halls in Montmartre to experience a social life unlike any other. In its heyday, the area was actually quite dangerous, but it has since been romanticized and sensationalized so that images and music associated with it evoke great nostalgia. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec frequently visited the Moulin Rouge, a nightclub in the neighborhood. As such, he was very familiar with the other regulars. In At the Moulin Rouge, he was able to capture these characters on canvas and portray the true grunge of the Paris nightlife culture. Using bright colors and thick brush strokes, Toulouse-Lautrec paints in an Avant-Garde style, apt for his subject matter. What is the Moulin Rouge? Established in 1889, the Moulin Rouge was a cabaret and nightclub located in the Montmartre district of Paris. Featuring live performances from the stars of Paris, drinks, and room for socialization, the Moulin Rouge was a truly modern space. The iconic can-can dance was first performed at the Moulin Rouge, and, at the time, it was considered a very improper dance. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec created several advertising posters for the Moulin Rouge, as well as several paintings of the Moulin Rouge. Among those paintings are At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and La Goulue at the Moulin Rouge in the Museum of Modern Art.

Who is Toulouse-Lautrec? Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec was born in Albi, France in 1864 to a wealthy family. As his mother and father were first cousins, Toulouse-Lautrec suffered from congenital health issues that affected his bones and growth. Due to these health issues, he became slightly isolated from society and spent his time making art. Painting in the Post-Impressionist style and printmaking in the Art Nouveau style, Toulouse-Lautrec captured the Bohemian lifestyle of 19th-century Paris. This was the lifestyle Toulouse-Lautrec immersed himself in Montmartre’s Moulin Rouge. He created a series of posters advertising the cabaret and displayed his artworks there.

Fun fact: The two men walking behind the table in the center of the painting are actually Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec himself and his cousin, Dr. Gabriel Tapié de Céleyran.

Where? The Crossing of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.

When? Carved between 1629 and 1640. Commissioned by? Pope Urban VIII and created under the direction of Gianlorenzo Bernini. What do you see? The statue of Saint Veronica is of colossal size, measuring 5 meters (almost 16.5 feet) tall. The choice of marble colossi for the crossing bears the influence of the Pope, as the colossus was a sculptural type considered one of the most impressive accomplishments of the ancients and was also closely associated with Michelangelo. In fact, the earliest records related to the effort to obtain marble for the four crossing statues indicate that it was initially hoped that each statue would be carved from a single colossal block, similar to Michelangelo’s David. However, this was not the case as each figure was made from multiple blocks. Nevertheless, Saint Veronica is only centimeters short of Michelangelo’s David, though one might not suspect that due to the disorienting scale of St. Peter’s Basilica. At five meters high, Mochi’s Saint Veronica is half a meter higher than the three other colossi, despite the fact that it is the only figure that leans forward rather than standing fully upright. Also, unlike the other three statues, Saint Veronica is not made from two primary blocks, but, as Mochi is quoted, from “three great blocks, put together in a most difficult way in which the joins are never seen again.” Mochi’s seamless and ingenious construction from three separate blocks made the dramatic forward lean of the figure possible, speaking to the balance of technical and formal invention in Baroque sculpture. At the left rear of the figure, Mochi carved his signature, indicating through this symbolic counterweight his literal and figurative balancing act in Saint Veronica. Backstory: In 1624, Bernini was at work on the Baldacchino marking the high altar of St. Peter’s, and over the next several years, ideas for housing the basilica’s most prized relics in the crossing piers evolved through discussions with the Pope. The need for altars associated with the relics was strongly felt for liturgical and devotional purposes. While this plan for honoring the relics through sculpted altars remained unchanged, a recognition that the new basilica required a solution more appropriate to the grandeur of the crossing led to the introduction of a new element: colossal marble sculptures.

Where? The Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham, England.

When? About 1800 Commissioned by? Most likely painted for the Golovine family. The painting remained in their possession until approximately 1978, when it was acquired by Gooden and Fox, then it was sold to the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in 1980. What? Oil on canvas, octagonal, 32 7/8 by 26 1/4 inches (83.5 by 66.7 cm.) What do you see? No matter what room this portrait of Countess Barbara Nicolaievna Golovine is in, it will be the first painting to demand attention. The innovative composition is a half-length figure in an octagonal shape and is further enhanced by an attractive gold frame. Vigée Le Brun has wrapped her subject entirely in a large, thick, rich, red stole with gold embroidered trim. The luxurious wrap is draped carefully but casually, and held gracefully at her neck by one hand, as if she has just come from her boudoir or the bath. The red shawl commands immediate attention. Her loose and free, brown, curling hair tumbles around her face and shoulder, held in place by a deep golden headband that has a twist and texture that adds to the framing of her face. There is a dimple in her chin that augments the slight smile on her face and blends gracefully with the shadows of the light and dark. In fact, the dimple makes her face much more interesting. The neutral, scumbled background has a diagonal shaft of light cutting across the canvas that adds clarity to her hand and facial features. It is an unusual backdrop that suits the countess’s dynamic pose. She faces us, while her body turns slightly to the left, suggesting motion. There is an erotic hint to the painting but that is over-whelmed by the soft smile and the warmth of her eyes as she engages the viewer. She is pleased to see her visitor, a friend, a well-liked friend, who will be welcomed and entertained with excellent conversation, perhaps a glass of French wine, for she was a member of the Russian Aristocracy, a Princess first, then a Countess, when friendships, manners and virtue mattered more than anything. As the viewer turns away, moving either to the left or right, a glance over a shoulder confirms that her eyes are following as she bids her farewell……it is not a portrait easily forgotten by anyone who views it, and one that many, return to view again and again.

What do you see? The Santa Maria del Fiore (Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower) or The Cathedral of Florence in The Piazza del Duomo is one of the most recognized buildings and piazzas in the world. The piazza includes the Florence Cathedral, Giotto’s Campanile (The Bell Tower), and the earliest building, the Baptistery. The octagonal dome, with its lantern and golden ball at the top, dominates the view. It is hard to move your eyes from the cupola but the golden orb and cross demand attention as they rest above the lantern and point skyward to the glory of God.

Looking at the exterior, the inlay of different colored marbles (green, pink, and white) in neat geometrical design is unique to Tuscany. The graceful circular windows interrupt the repetitious geometric patterns beneath the dome and add to the power of the dome itself. The continuation of the circular windows provides interest in the long exterior of the nave. On the right of the image is the separate Campanile or Bell Tower. Just to the right of the Campanile is the Baptistery (see images below). Incorporated into the three buildings are three main styles:

Definitions of Architectural Styles:

Where? Second floor, room 846 of the Richelieu wing in the Louvre

When? Between 1626 and 1628 What do you see? A prostitute smiling provocatively. She has half of her breasts exposed. The use of light emphasizes her expression and cleavage. She wears a white linen garment with a salmon-colored bodice on top of it. She has rosy cheeks and looks to her left (our right). It seems that she is seducing a potential client. By 17th- and 21st-century standards, the woman may not be very pretty. She has a somewhat big nose, not a very smooth skin, and her hair is somewhat unkempt. However, her facial expression is so intriguing that this work leaves a lasting impression on those who view the painting. Frans Hals used loose and rough brush strokes for this painting. While Hals is known for his loose brush strokes, in this painting he used them more than in most of his other works. The style used for this work helps to make The Gypsy Girl very memorable. Backstory: Louis La Caze owned this painting in the 19th century. He was a doctor from Paris and an avid art collector. He gave the name The Gypsy Girl to this painting. This title is not very accurate as he did not recognize that Frans Hals actually painted a prostitute (though she may have been a gypsy). La Caze left this painting for the Louvre after his death in 1869, together with 568 other paintings. When the Louvre received the painting, the influential newspaper Gazette des Beaux-Arts praised Hals as the best painter ever. Malle Babbe: This painting is also sometimes referred to as Malle Babbe. However, this name is incorrect as Hals has another painting entitled Malle Babbe. This painting is in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. The confusion can be explained as a popular Dutch song, entitled Malle Babbe, was written in 1970. This song was inspired by the Gypsy Girl. However, the writer of the song, Lennaert Nijgh, mistakenly thought that The Gypsy Girl painting was called Malle Babbe.

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was born in 1582 or 1583 in Antwerp, Belgium, and died in 1666 in Haarlem, The Netherlands. When Hals painted The Gypsy Girl, he was inspired somewhat by the works of Caravaggio. However, Hals differed substantially from Caravaggio as he left out many (distracting) details in his paintings and focused on the composition and the expression of his subjects. This allowed Hals to give his subjects a personality.

While Hals was a popular local painter during his life, his works were largely forgotten after his death. The Impressionist painters rediscovered his work in the 1860s. Artists like Manet and Monet were inspired by the lack of detail, beautiful composition, and the loose brush strokes of Hals. The work of Hals has only gained in popularity since. Some beautiful works of Hals include his series on the four evangelists, of which Saint John the Evangelist is in the Getty Museum, and the Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Fun fact: Radiographic analysis of this painting revealed that Frans Hals initially wanted to paint a less provocative version of this woman. Her breasts were smaller and less exposed. However, Hals decided to make the painting more provocative. This painting shows more cleavage than any other painting by Hals. The open mouth of the woman is also a telltale sign. Decent women from the 17th century would never be depicted with a smile or open mouth in a portrait as that was considered indecent.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster.

Where? The Oval Drawing Room of the Wallace Collection

When? 1767-1768 What do you see? Golden light pours through the trees of a garden. A young woman in a brilliant pink dress sits on a large swing that is attached to the trees behind her. She kicks off one of her pink shoes (look above her raised foot) in the direction of the statue of a cupid on the left. As her skirt flares upwards, her young lover in the lower left is taken aback by the sight before him. He has his hat in his left hand. Unaware of the scene in front of him, an older man smiles as he operates the swing in the lower right. Near his feet is a little white dog that perhaps symbolizes an ironic fidelity. The sculpture of the cupid on the left was created by Étienne-Maurice Falconet in 1757 and versions of this statue are in the British Museum, Louvre, and the Rijksmuseum. It is popularly known as Menacing Love, and shows cupid looking down on the scene while putting a finger to his lips saying: “this is a secret.”

Backstory: This painting is also known under the more complete title “The Happy Accidents of the Swing.” This title refers to the erotic references in this painting. The man that is hiding in the bushes on the left has a chance to look at the woman’s legs under her skirt. The slipper that the woman kicks in the air and the hat of the man are a reference to their sexual availability. The statues of the cupids confirm the sexual intentions of the couple even more.

Fragonard’s painting soon gained recognition, and he became popular with a small group of patrons with a taste for erotic works as well as history painting. As such, The Swing played an important role in boosting Fragonard’s artistic career. Who is Fragonard? Born in 1732, Jean-Honoré Fragonard was a French Rococo painter. As a boy, he had a passion for drawing and eventually became the student of François Boucher. In 1752, Boucher suggested Fragonard to apply to study under Carle Van Loo, the court painter to Louis XV. This involved studying at the French Academy in Rome. While there, Fragonard made many sketches of the countryside and copied many Baroque-style paintings by Hubert Robert. His good work in the Academy was admired by many, and even Louis XV purchased one of his artworks. Fragonard soon gained more recognition and earned a studio in the Louvre Palace as well as the title of an Academician. Over time, Fragonard painted in many styles: Baroque, Romantic, and Rococo. In addition, he painted a variety of paintings, including landscapes, portraits, party scenes, and religious paintings. As his frivolous Rococo paintings were not also easy to sell, he also created some more traditional works on commission, such as the Education of the Virgin in the Legion of Honor Museum.

What is Rococo? An art style popular between 1720 and 1780 in Europe. The style is relatively chaotic and theatrics, leading to artworks that are full of drama, emotion, and movement. The style is highly feminized and popularly used in the French salons run by women in the 18th century. Some of the most successful artists following this style include François Boucher, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, and Antoine Watteau.

Fun Fact: Fragonard was not the artist originally commissioned to paint the swing. At first, Gabriel-François Doyen was given the task by an anonymous man of the court. He had requested a painting of his mistress being pushed on a swing by a bishop as he admired her from below. However, Doyen turned him down. Instead, Fragonard took up the task. Fragonard did not follow all the instructions of the commissioner and kept his own artistic freedom. For example, he decided against painting the man pushing the swing as a bishop. And he included some extra details to the painting such as the little dog, statues of cupids, and the lost slipper.

Where? Gallery 17 of the Legion of Honor Museum

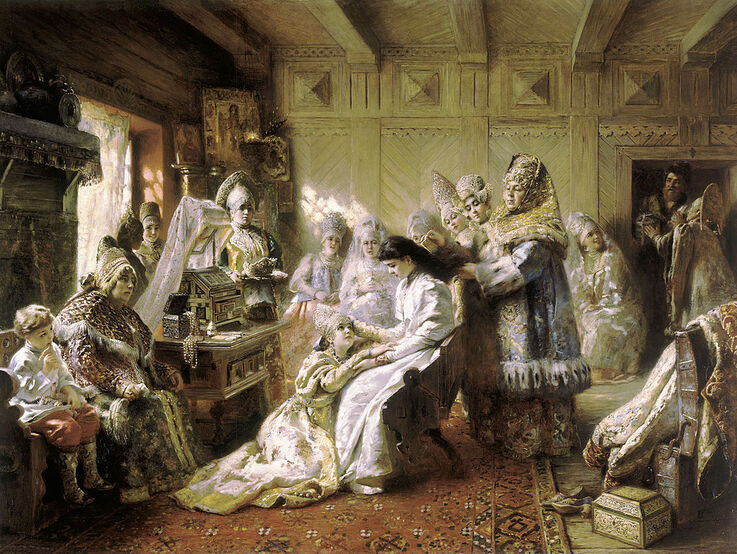

When? 1889 What do you see? A life-size depiction of a scene before a 17th-century Russian wedding. The girl dressed in white in the center is about to get married to the tsar. She looks pale, and her sister is at her feet. The bride did not choose her partner, and she is not looking forward to the wedding and the rest of her life. She will have to give up her happy life as a teenager and faces a life in which she will have to do whatever the tsar demands. Most of her female friends and family members surrounding her share the somber mood. The mood is in stark contrast with the sumptuous, colorful outfits of the wedding guests. Tradition prescribes that only women can be present while the bride is prepared for the wedding. An exception is made for the little boy sitting on the left. However, the man entering the room – possibly the bride’s father - is not welcome and is urged to leave the room. Backstory: The bride’s name is Maria Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya. She is about to get married to the 18-year old Tsar Alexis I. Makovsky created two versions of this painting. The first version is on display in Serpukhov`s Museum of History and Art. This version is much less colorful and almost eight times smaller than the version in the Legion of Honor. Makovsky used his second wife as the model for the bride in this painting. When this painting was traveling through the United States in 1893, Michael Henry de Young bought the painting. He left the painting for the museum that was eventually named after him, the De Young Museum, which forms together with the Legion of Honor Museum the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Bridal theme: Makovsky enjoyed painting the 17th-century life of the Russian upper class. He created several portraits and large paintings on this topic. Among his paintings is also The Choice of the Bride in the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. In this painting, potential brides for the tsar line up and the tsar can choose who he wants to marry. The young women have no say in this as the tsar’s word is law.

Who is Makovsky? Konstantin Yegorovich Makovsky was born in 1836 in Moscow. The artistic gene ran in the family as his father and brothers were artists as well. He was one of the most successful Russian painters of his generation and loved to spend his earnings on traveling across the world. He died in 1915 in Saint Petersburg.

His works are a combination of the Realist and Academic art styles. He painted a variety of themes, including historical and mythological topics, genre pieces, and portraits. His most famous mythological work is probably The Judgment of Paris in the Faberge Museum in Saint Petersburg. A nice example of Makovsky’s portraits is the Portrait of Varvara Bibikova in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

Fun fact: The size and colors make this painting look very impressive. One is inclined to think at first glance that Makovsky painted a happy occasion. But a better look at the bride tells a different story. This story is emphasized by the faces of the other guests in the room. They do not look happy either. However, Makovsky did not make an effort to express much emotion on these faces. They mostly look dull and expressionless.

While Makovsky was an accomplished portrait painter, he clearly did not make a big effort in painting meaningful faces and expressions. Instead, he focused on the coloring, which was his main interest during this stage of his career. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster

Where? Room 254 of the New Hermitage building in the Hermitage Museum

When? 1668-1669 What do you see? Six(!) people in front of an arched doorway. On the left, an old man lovingly embraces a young and bold man who bows his head in humility. This is his son who returned home after a long time. While the father is dressed in beautiful clothes, the son is not. He wears old clothes with holes in it, and his sandals are worn and broken. He still wears the dagger on his belt that he needed to defend himself in the outside world. On the right, at a little distance, is the older son of the old man. Dressed in a red cloak, he has his hands folded while holding a cane. He looks at his younger brother with a mix of disapproval and envy. It is not certain who the other three people in this painting are. The woman in the middle background may be a sister or the mother of the prodigal son. The seated man with a mustache may be an older servant. On the top left, barely visible, is the silhouette of a female servant. Rembrandt uses light to emphasize the important aspects of the painting. The father and son are fully in the light, the older son is partially in the light, and the other people are in the darkness. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us