|

What do you see? The Santa Maria del Fiore (Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower) or The Cathedral of Florence in The Piazza del Duomo is one of the most recognized buildings and piazzas in the world. The piazza includes the Florence Cathedral, Giotto’s Campanile (The Bell Tower), and the earliest building, the Baptistery. The octagonal dome, with its lantern and golden ball at the top, dominates the view. It is hard to move your eyes from the cupola but the golden orb and cross demand attention as they rest above the lantern and point skyward to the glory of God.

Looking at the exterior, the inlay of different colored marbles (green, pink, and white) in neat geometrical design is unique to Tuscany. The graceful circular windows interrupt the repetitious geometric patterns beneath the dome and add to the power of the dome itself. The continuation of the circular windows provides interest in the long exterior of the nave. On the right of the image is the separate Campanile or Bell Tower. Just to the right of the Campanile is the Baptistery (see images below). Incorporated into the three buildings are three main styles:

Definitions of Architectural Styles:

Statue of Santa Reparata Statue of Santa Reparata

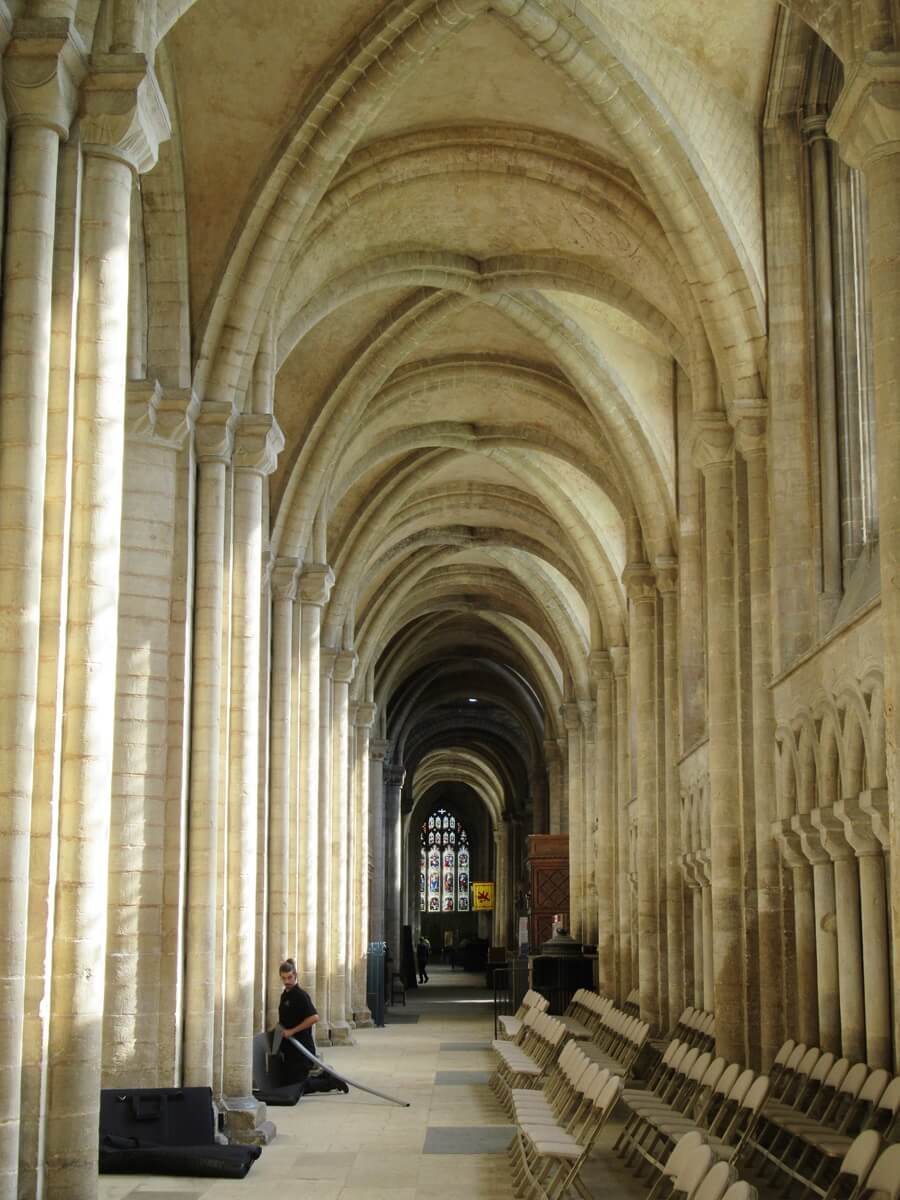

Seen in all gothic styles are remains of classical architectural features combined with the new gothic characteristics and the individual differences between regions.

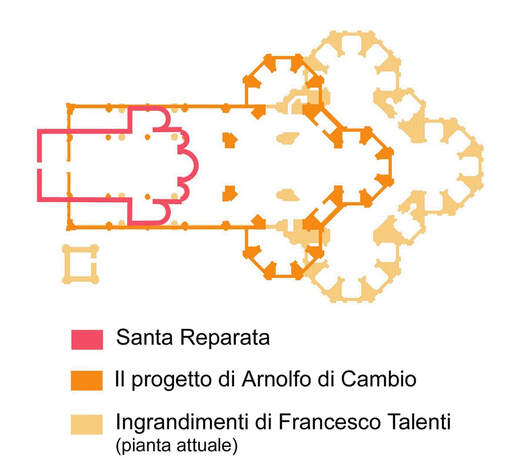

Background story: To truly explain the raising of the dome on Santa Maria del Fiore, some of the history of the people involved and what went before makes the tale even more intriguing. We need to see the building in the late 1200’s through to its structural completion in 1436. Ever since the 1st Century A.D., there has been a religious presence in the form of a building on the site of the Florence Cathedral. Saint Reparata was an early virgin martyr to Christian beliefs, who is considered to be the co-patron saint of Florence. The Cathedral of Santa Reparata was opened in the first century in honor of her. A variety of legends about battles won were associated with the church. The much smaller building was over-built several times until in 1294, the design of Arnolfo di Cambio started to become a reality. Today, the remains of Santa Reparata can be seen underground in the Florence Cathedral. Excavations in 1965 and 1974 have shown that this ancient building is the most concrete evidence of the early Christian Age in Florence. A coin found in the Roman soil belonged to the time frame of 238-244 AD. A mosaic floor with a peacock confirms the dating to the Roman Empire. Arnolfo di Cambio: Di Cambio (c.1245-1301/1310) was an Italian architect and sculptor whose designs belong to the transition between the late Gothic and Renaissance architectural features. Reportedly, learning to paint with Cimabue and then studying sculpture with Nicola Pisano, he spent much time working throughout Italy. He returned to Florence in 1296, when he was commissioned to take charge of the design and building of the cathedral there. His was the first real plan for the Duomo and he drew inspiration from contemporary French monastic constructions. It was supposed to be one of the largest churches in all of Christendom. He was also charged with carving the statues for the façade of the duomo. (The façade was destroyed in 1589, but his sculptures have been preserved in the Museum of the Duomo and more recently a full size replica of this façade has been built and is being displayed in the new museum.) Whatever possessed him to build this enormous cathedral but to leave a huge hole where the dome should be, is inexplicable. He knew he was without the skills to complete the dome but he must have believed that God would somehow supply the person able to do it in the future. Little did he know that it would take almost 140 years for that to happen. Progress: The diagram below shows how the building grew in size, yet kept to the original concepts. Arnolfo’s design, approved by the city council, consisted of 3 wide naves ending under an octagonal dome. The middle nave covered the area of the original Santa Reparata. The first stone was laid in 1296 by Cardinal Valeriana, who was also the first papal legate ever sent to Florence. Arnolfo died in 1302 and further building came to a stop for about 50 years. He had been recognized by his contemporaries as one of the leading artisans of the day and he left his mark permanently in Florence with his contributions to the architectural and sculptural beauty of the city (like the Palazzo Vecchio and the Church of Santa Croce) In 1330, the relics of Saint Zenobius (337-417 AD: first Bishop of Florence), were found on the site and by 1331, the interest in the relics had grown to such an extent that the wool guild took over patronage of the construction of the cathedral. Their great wealth enabled them to appoint Giotto to oversee the work. He was mainly interested in building the Campanile and by 1337, he had also died, leaving his assistant, Andrea Pisano to continue the work. Everything halted in 1348 as the Black Plague descended on Europe and decimated the population. Florence had a population of 50,000, about the same as London at the time. The city lost almost half of their people. Francesco Talenti was eventually appointed to finish the campanile and it was he, who enlarged the overall project of the cathedral.

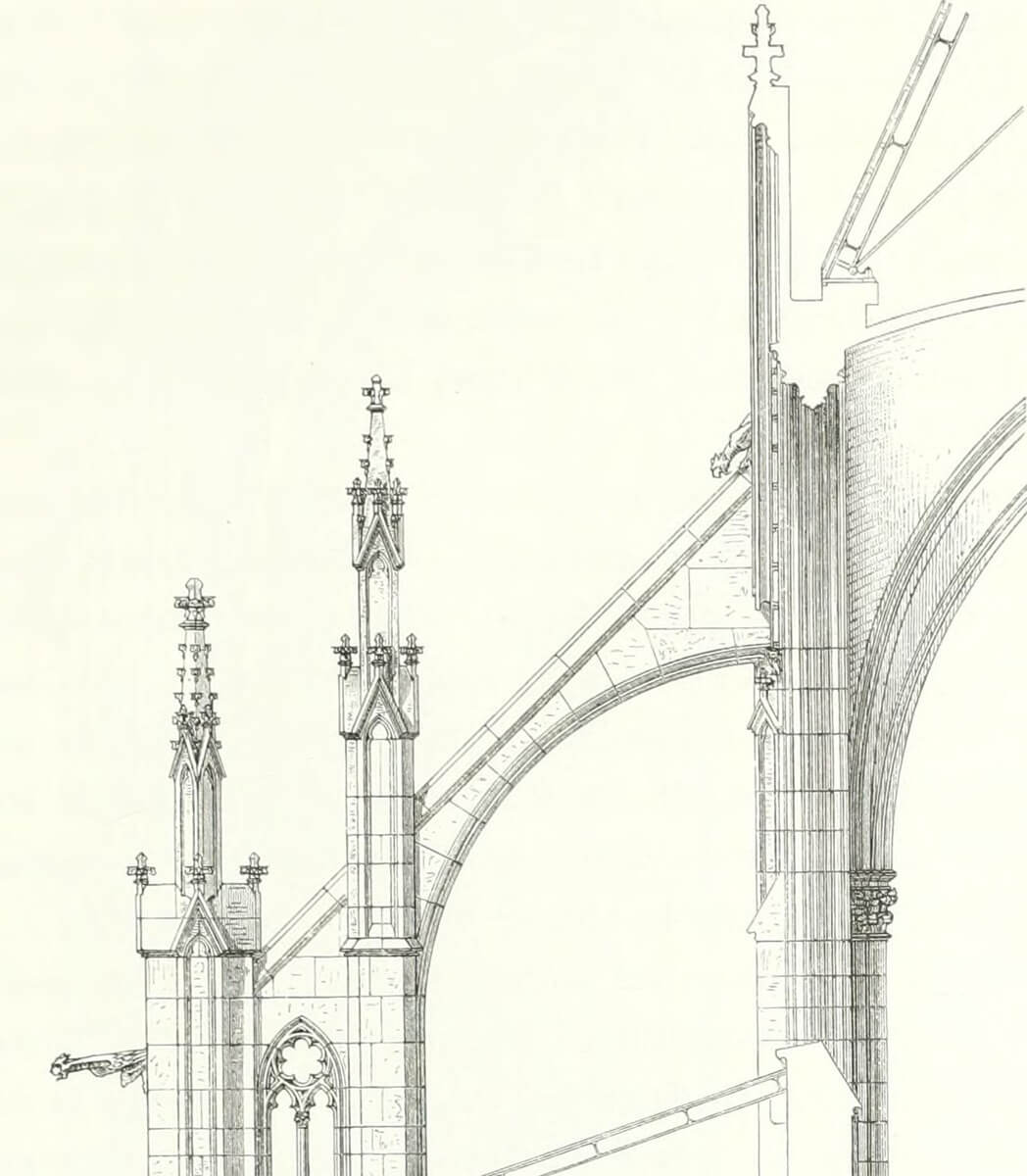

From 1359, various other architects and builders were appointed to the position. In 1366, The capomaestro of the cathedral was Giovanni Lapo Ghini. He had begun to build a model for the dome itself but he was using external buttresses that as mentioned earlier, the Italians found clumsy, awkward and ugly. Add the political enemies, The Goths, who were considered to have created these forms in architecture, and it is understandable that his model was not popular. The wool merchants had asked Neri di Fiorvanti, a master mason, to also produce a model. He had experience with vaulting and predicted the dome could be held up by a series of stone or wooden chains that would run around the circumference of the dome, similar to an iron hoop that goes around the planks of a barrel. These rings would be invisible and support the weight of the dome at any points of stress. His ideas excited the people of the city but still brought questions about the stability of the design.

After much discussion of the pitfalls involved with the dome and what its dimensions should be, the citizens of Florence voted in a referendum on November of 1367 to adopt Neri’s design. The dome would have a diameter of 43 meters (141 feet) and that would make it bigger than the Roman Pantheon, the world’s largest dome at the time. The walls of the cathedral were already 43 meters high, and the drum or tambour was another 9.15 meters. The cupola would rest on the drum and the vaulting for it would begin at the height of 51.81 meters above ground. In 1375, the old Santa Reparata was completely pulled down (leaving only a cornerstone incorporated into the lower level of the final cathedral) and it wasn’t until 1380 that the nave was finished. That left the unfinished dome area open to the elements. Rain, wind, sun, beat down on the inside of the building. It took another 38 years for anything more to happen. No one knew how to erect a dome that large.

The Dome: The “Opera del Duomo” or “works commission” was founded by the Republic of Florence in 1296 to oversee the construction of the new cathedral and its bell tower. To this day the commission has done its job and the “Museo Dell Opera Del Duomo” has been responsible for preserving, recording and restoring all that is “The Cathedral” ever since.

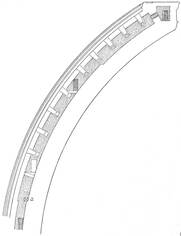

This image shows a simple diagram of the open top of the dome. Construction would start at 170 feet in the air with a difficult octagonal shape to be covered and built to withstand all the downward, inward and pressure stresses involved.  Italian gold Florin with St. John the Baptist Italian gold Florin with St. John the Baptist

Imagine in 1418, being a member of that illustrious group of businessmen who formed The Opera del Duomo, standing, looking up at the cathedral with this great gaping hole, wondering how a dome of that size would ever be completed? It was decided that there would be a competition and the following announcement was made, August 19, 1418:

“Whoever desires to make any model or design for the vaulting of the main Dome of the Cathedral under construction by the Opera del Duomo—for armature, scaffold or other thing, or any lifting device pertaining to the construction and perfection of said cupola or vault—shall do so before the end of the month of September. If the model be used he shall be entitled to a payment of 200 gold Florins” (from Brunelleschi’s Dome by Ross King). It is almost impossible to say what that would be worth in today’s world but looking at the gold alone, $187/coin, it would be approximately $37,400, a good sum, one would think in 1418. Once the competition was announced, architects from all over Europe traveled to Florence, hoping to win the commission that would bring them fame, fortune and world renown. They had a scant 6 weeks to produce a model. The Rivalry: In 1401, two of the main contestants, Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi, had clashed previously over the set of new bronze doors for the Baptistery. Six people participated in the competition and they were given a year to produce a bronze panel depicting the Sacrifice of Isaac. Each had to model a clay figure, carve it, bake it, then pour bronze into the hollow sculpture. The panel then had to be chiseled, engraved, polished and gilded. It was a complicated process and took great skill.

When they were finished, the judges had a difficult time deciding who should be responsible for the panels that would adorn the North door of the Baptistery. Only the two above were considered good enough, and each had their own interesting features. Brunelleschi’s panel was very dramatic, and more progressive in style, with the moment Isaac was about to slay his son, until the angel stayed his arm. But the judges believed that Ghiberti’s panel, more conservative and traditional in style, was the more elegant of the two. In the end, Ghiberti won the commission. There are two versions of what followed. In one, it is said that Brunelleschi was so furious that he had lost that he withdrew from the competition and left Florence. In the other version, he was unable to cope with such a great disappointment and that he then left the city. Regardless of what might be the truth, Brunelleschi took himself off to Rome, where he lived for the next ten to thirteen years with the occasional return to Florence. He was accompanied by his friend Donatello, the great sculptor who was also angered by his loss in the competition.

Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455): Born in Pelago not far from Florence. His paternity has always been a mystery as his mother had a common law marriage with a goldsmith named, Bartolo de Michele while her legal husband, Cione di Ser Buonaccorso, remained alive. Bartolo however, was the only father that Ghiberti knew and he trained Lorenzo as a sculptor and a goldsmith. He learned much about design and remained interested in other art forms including painting. It was the competition for the Baptistery Doors that brought him back to metal work. His win and the beauty of the doors that he produced brought him fame and wealth in his early twenties and he was able to maintain a large workshop, employing many artisans. As a wealthy man, who was considered to be charming and affable, he became a prominent society figure with only one regret… that his illegitimacy prevented him from ever holding political office.

Filippo de ser Brunelleschi (1377-1446): Also a designer, goldsmith and sculptor but by that twist of fate, in 1401, he is now considered to be the founding father of Renaissance architecture. He was born in Florence. His father was a well-known Florentine, a notary and a civil servant. His mother was a Spini, and her family palace is still just across from the Church of the Trinita in Florence. Filippo was to follow in his father’s footsteps but he showed a flare for art and when he was 15, he became an apprentice at the Arte della Seta, the silk merchants guild. This also included the study of jewelry and metal work. By 1398 at the age of 21, he became a master goldsmith and a sculptor working with cast bronze. These two young men who competed so closely for the Baptistery Doors at the early ages of 23 and 24 would find themselves competing yet again some 18 years later when it was finally time to find the man who could bring the designs for the cupola to life in order to finally finish the cathedral. The charming Ghiberti and the somewhat grumpy Brunelleschi would spearhead the explosion of talent and artistry that would become the Renaissance. Ghiberti spent the next 50 years creating and casting not only the North doors of the Baptistery but also the second set of doors that Michelangelo would name The Gates of Paradise.

These two sets of doors with original and exquisite work, brought him fame. He continued to develop many facets of art and design so that he still felt able to challenge all comers when the competition was announced for the Dome of the Cathedral in 1418, even though he had little or no experience with architecture.

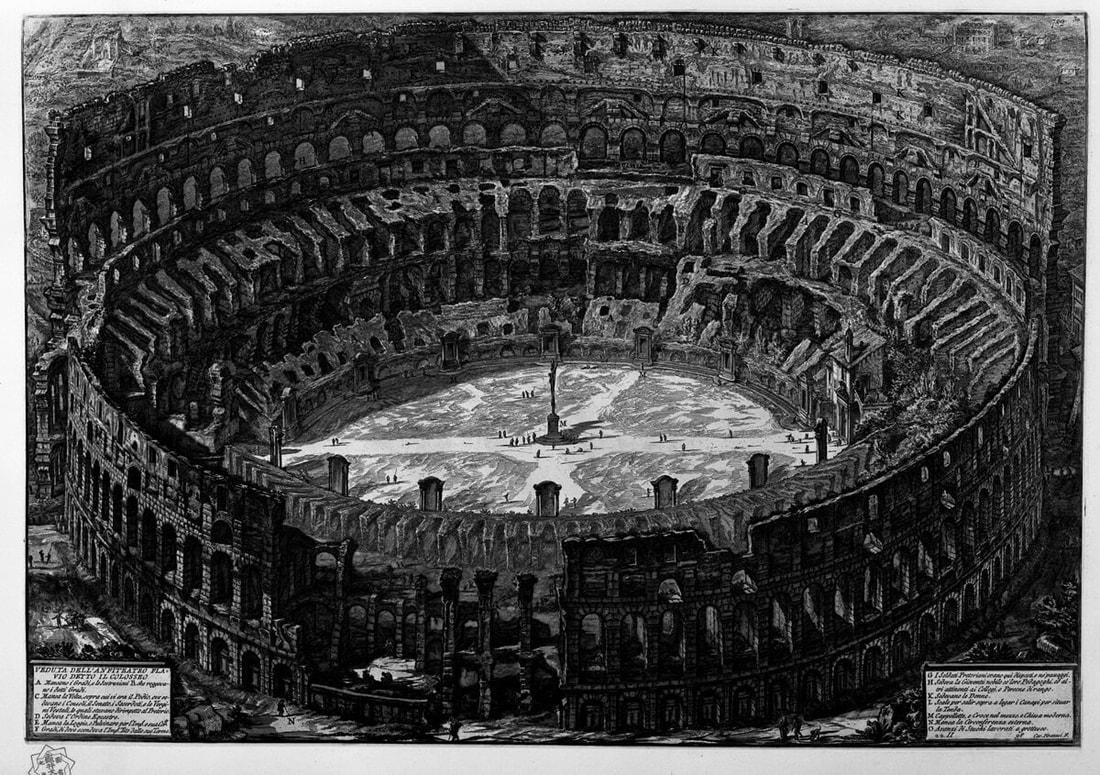

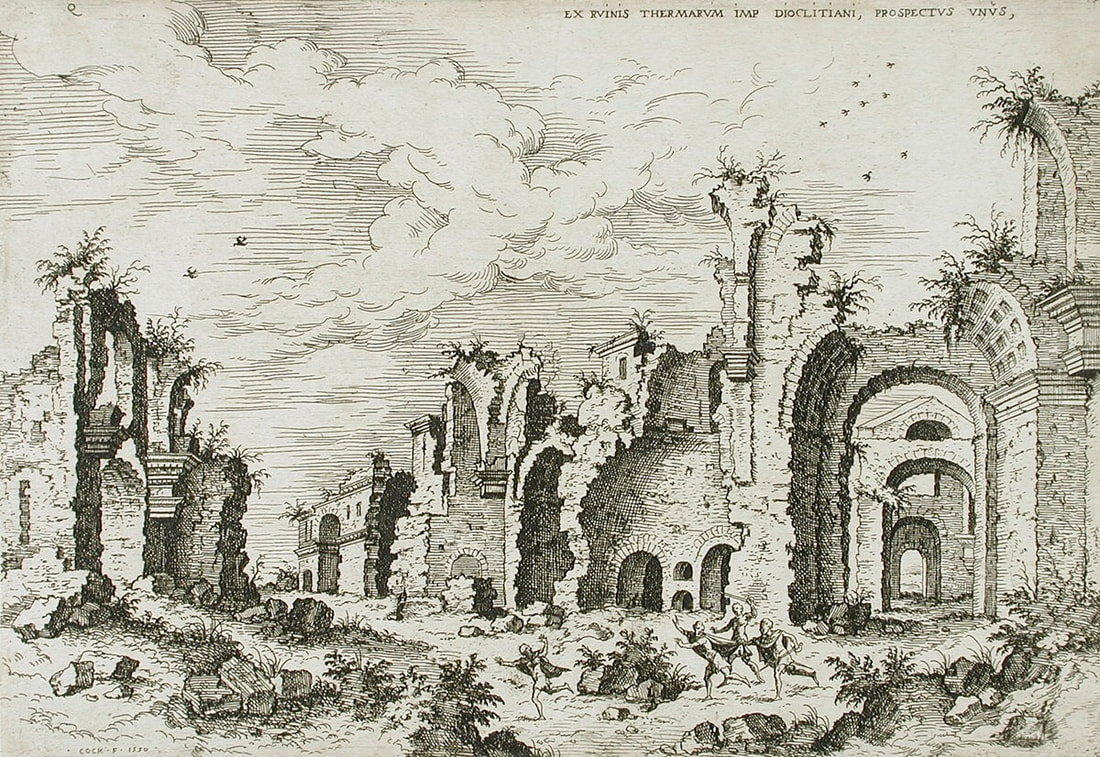

Brunelleschi and Donatello’s years in Rome were not wasted but they lived in a Rome we can only imagine. Like Florence, its population of one million had been decimated by the 1348 pandemic and only twenty thousand lived there in the early 15th century. Recovery was delayed for many reasons. The 14th century had been one of deep neglect and misery in Rome. The absence of the Pope, still with the center in Avignon, France, left the city without leaders. People lived in poverty and starved. Thriving trade never returned and the economy was in collapse. There was anarchy in the city because of the struggles between the nobility and the popular faction. Crime ran rampant in the streets. All signs of the ancient Roman era were vilified for the pagan beliefs that continued into the early days of Christianity. The persecution of the early Christians was a recent and resented history. Roman buildings had been left to ruin, ignored, torn down and the stones used for other buildings, some even exported as far as England. The pair from Florence “arrived in this squalid, crumbling city” and according to Ross King, “lived like vagabonds, paying little attention to what they ate, how they dressed or where they slept. Together, they began digging in the ruins, hiring porters to cart away the rubble and becoming known to locals as the “treasure hunters”, because it was believed they were searching for gold coins”. Donatello was interested in the ancient statues and Filippo studied the ancient ruins while pretending to be doing something else. Even Donatello did not know what his secretive and suspicious friend was up to. Brunelleschi was surveying, observing, looking, seeing, measuring, and recording, to figure out how the ancient buildings had been constructed. It was during this time, when Brunelleschi continued to support himself as a goldsmith, that he was turning himself into an architect. What secrets did he extract from The Pantheon, The Colosseum, The Baths of Diocletian, The Temple of Fortuna Virilis, and The Golden House of Nero to name just a few of the ancient and classical Roman buildings that he studied? The Pantheon vault, the stonework in the Colosseum and perhaps the metal working in the Baths were his teachers.  Two shell connecting diagram Two shell connecting diagram

Filippo had lived near the Cathedral in Florence all his early life and he knew that the dome had to be constructed sooner or later. By the time he returned to Florence, (approximately 1417-18) he had convinced himself that he was the only man who could do it. His bad temper and arrogance had not been quelled by his time in Rome, and he was out to prove what he could do. He must have identified many of the problems that needed solutions while he was in Rome.

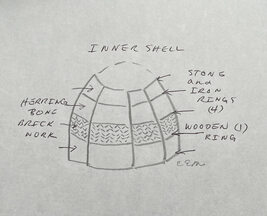

What were the Problems? Filippo had to be certain that the columns already built were strong enough to support the weight of the cupola and would be able to spread the effects of the compression over a greater surface. Ross King discussed the strength of stone as an example: “a column of limestone could be built to a height of 12,000 feet or over two miles high, before it would start crushing the base under its own weight.” Part of Filippo’s solution was to build an inner and an outer dome that would direct the tremendous weight to the ground. The inner shell would bear the majority of the weight while the outer shell would protect it from the elements, thus preserving all the masonry that was involved and helping to prevent collapse over time. The connecting ribs between the two shells would allow further support, stability, and balance in the whole design. The simple side section diagram shows the two shells and the connecting ribs that partially distribute the weight of the dome. The space between the shells is large enough for stairs and if you visit the Cathedral today and climb to the lantern, you walk on the same steps that the workmen used in the 15th century. The vaulting in the dome had to be self-supporting. Brunelleschi had to find a way to deal with lateral thrust. If you blow up a balloon and then squeeze the top and the bottom, you will have a bulge in the middle. The balloon is flexible and can deal with this pressure or “tension” but the bricks, stones and mortar are not that malleable.

In order to support the vault and brickwork, Filippo added 4 stone, horizontal rings with iron chain hoops on their outside perimeter that connect each section of the dome. The rings encircle the dome in ever decreasing circumference from the bottom of the dome up. Between the first and third ring, there was also a fifth wooden one. The five rings work much the same as the iron bands around a barrel, eliminating the lateral thrust that would cause collapse. The unpopular, dreaded buttresses were not needed because of his novel solution. The schematic diagram of the inner shell illustrates his ideas.

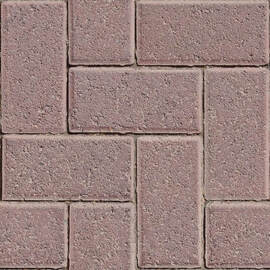

Example of Herringbone Brickwork Example of Herringbone Brickwork

A recent study undertaken by The University of Bergamo and the University of Princeton (Double Helix of masonry—researchers uncover the secret of Italian Renaissance domes) has shown that the herringbone patterned brickwork that Brunelleschi used on the inner shell produced a self-sustaining stability that prevented not only collapse of the dome but also negated the necessity for a scaffolding to hold the dome up while it was being built. The interlocking bricks controlled the stress and strains within themselves to prevent collapse of the walls and breakage of the bricks. The mortar needed time to dry, and this self-sustaining design gave the time necessary for the mortar to dry and further strengthen the walls. Brunelleschi left no notes so it is not clear where or how he heard or saw this technique but the proof that it works lies in the fact that we can still visit the dome, 500 years later.

The bricks provided the stability for the octagonal shape which was partially maintained by the defining vertical ribs of each section of the dome. There were eight vertical ribs on the outside and 16 hidden inside. The exterior and interior ribs, as well as the two shells provided “scaffolding”, to use the term lightly, to build each layer of stone and brick on the next without need for timber scaffolding or filling the interior space of the cathedral with earth or rubble to support it while the masonry dried. Apparently, the workers dispersed the bricks using a system of strings attached to a ring at the base of the dome.

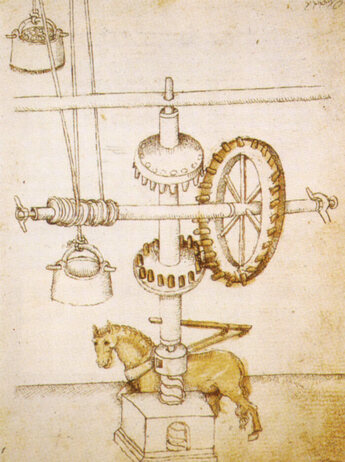

Below you can see the marble vertical ribs (white) on the outside of the exterior shell. The outer shell was constructed by using nine masonry rings that were much lighter than those on the inner shell. They encircled the dome in the same manner as the inner shell but at nine levels from bottom to top.  Drawing of Brunelleschi's Hoist by Taccola Drawing of Brunelleschi's Hoist by Taccola

These solutions all worked to provide the structural support and stability necessary to contain 4,000,000 bricks, and the sandstone rings, about 37,000 tons. His genius and doggedness in successfully raising the dome is a feat still admired by architects today.

The theoretical problems were not all he had to deal with. As the capomaestro, he was responsible for everything to do with the construction. He ran into many roadblocks and frustrations from dealing with politics that surrounded building such a cathedral dome, to finding all the supplies for the task: workmen, mathematicians, engineers, bricks, mortar, and marble, and he even ended up making certain that his workmen were fed on the site. He wanted the work to proceed easily and watered down the wine of the workmen to keep them sober and safe. He added a safety net to prevent anyone from dying in a fall. His training as a goldsmith dealing with clocks and watches had taught him how cogs and wheels and levers work, and he put this knowledge to work on a larger scale to invent huge machines that facilitated the construction of the dome. Nothing of this nature had been done before and each step demanded invention from him. Paola dal Pozzo Toscanelli was a mathematician who taught Brunelleschi the principles of geometry. His calculations helped with the construction of the scaffolding and hoisting machinery. One of the most important machines he made was the hoist with the world’s first reverse gear. The bricks and sandstone beams for the rings had to be raised up to the level of the dome. The animal, be it a horse or an ox, could move in one direction without interruption and the hoist could go up or down.  Il Badalone by Taccola Il Badalone by Taccola

Marian de Jacopa (1382-C.1453) called Taccola (the jackdaw) was an Italian polymath, artist, engineer of the early Renaissance. He was named the “Sienese Archimedes,” and his drawings of lifting devices and gear systems and novel ideas deeply affected the artists of the Renaissance and, in particular, the realization of this amazing Brunelleschi hoist.

This was a time of “man and machinery” and not only Brunelleschi studied the cogs, wheels, measurements, weights, and used engineering discoveries in their work. Ghiberti, Giorgio, and Leonardo da Vinci are three to name just a few. The military also were interested in how these new ideas could improve their war machines. Slowly but surely, the dreams of those who had gone before were becoming reality.

Brunelleschi used another drawing of Taccola (above) in a fruitless attempt to find an inexpensive way to move his much-needed marble up the Arno River from Carrara to Florence. In the process, he was the first to obtain a patent for an industrial invention. It was a three-year monopoly for building a barge with a hoisting mechanism meant to lift the marble onto the barge, but it all ended in failure when the boat sank, including the marble in route back to Florence. He had to retrieve the marble and it all ended up costing him a fortune with great loss of face and they still used tomb marble for some of the construction, which of course, was more costly. Brunelleschi’s trials and tribulations were made more difficult by the insistence of the powerful commissioners that Lorenzo Ghiberti would share in the construction of the dome. Their rivalry continued throughout these years as a thorn in Brunelleschi’s side. Every idea, every model built had to be fought for before anything could be put in place, but at last, in 1435, the final stone chain which served as the closing ring at the top of the dome was finished. In 1436, 16 years after the dome was begun, Pope Eugenius IV, consecrated the cathedral and 6 months later, the cupola itself. The Lantern: This is not just a decorative or finishing addition to the dome. As a crown on the dome, it functions as a sort of tap and keeps in balance the pull and push forces that are created by the internal and external shells. The word actually means small structure. It also permits light into the interior of the cathedral.  Top of the Dome Top of the Dome

Filippo had every right to expect the commissioners to appoint him to design and finish the lantern for the top of the dome. However, they called for yet another competition and again Brunelleschi and Ghiberti were competing along with several others. More models had to be made and judged before progress could be made. In the summer of 1436, Brunelleschi started his design with the help of Antonio di Ciaccheri Manetti, a carpenter who had worked with him on other projects for the dome. Filippo made the drawing and Manetti was to produce the model. But Manetti had other plans and made his own model incorporating Brunelleschi’s ideas. Filippo had been paranoid about his ideas being stolen from as far back as the Baptistery doors and here, it actually happened. Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Manetti, and two others submitted models for the competition. The decision was made on the last day of 1436 and in the end, it was Brunelleschi who won. However, Brunelleschi would die in 1446, when construction was in the early stages and Manetti would have the final laugh, as he became capomaestro and completed the lantern in 1471, when the cross was set on top of the ball.

A million pounds of stone and marble had to be lifted to the top of the dome in order to build the lantern. Another hoist with a braking system was invented that allowed men to hoist these materials to their lofty construction site. Brunelleschi completed this design also. He did see the completion of his dome if not the lantern. Even his burial was controversial as there were factions who thought he should not be there, but in the end, they were overcome, and he was buried inside the cathedral. Florence: The Dome became a symbol of the prosperity of the city and its arts at that time. Academics, artisans, rich merchants, and humanists seem to form the background for the creativity and innovations which exploded in Florence between 1400 and 1500 and fueled The Renaissance. The engineering feat of erecting the dome included the rediscovery of ancient linear perspective. Brunelleschi’s role in this was spread far and wide and is responsible for so many of the changes that occurred in all the arts and some of the sciences. It literally changed the world. Fun Fact: The Opera House in Sydney, Australia, ran a competition for its design and construction in the 1950’s. Hundreds of designs flooded in from all over the world and the winner was Jorn Utzon, a 38 year old Danish citizen from Hellebaek. His was one of the last designs to be examined and it was definitely “modern”. The judges agreed, “Because of its originality, it is clearly a controversial choice. We are however, absolutely convinced of its merits.”

This beautiful building took years to construct with all the concert halls and venues enclosed in an inner shell and an outer shell of ceramic to protect it. What is old, is new again.

Written by Carol Morse

References:

2 Comments

4/5/2024 08:02:54 pm

Glad you enjoyed the post! The research for the article was interesting and the history made a great story to tell ! Thanks for your comment!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us