|

Where? The Crossing of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.

When? Carved between 1629 and 1640. Commissioned by? Pope Urban VIII and created under the direction of Gianlorenzo Bernini. What do you see? The statue of Saint Veronica is of colossal size, measuring 5 meters (almost 16.5 feet) tall. The choice of marble colossi for the crossing bears the influence of the Pope, as the colossus was a sculptural type considered one of the most impressive accomplishments of the ancients and was also closely associated with Michelangelo. In fact, the earliest records related to the effort to obtain marble for the four crossing statues indicate that it was initially hoped that each statue would be carved from a single colossal block, similar to Michelangelo’s David. However, this was not the case as each figure was made from multiple blocks. Nevertheless, Saint Veronica is only centimeters short of Michelangelo’s David, though one might not suspect that due to the disorienting scale of St. Peter’s Basilica. At five meters high, Mochi’s Saint Veronica is half a meter higher than the three other colossi, despite the fact that it is the only figure that leans forward rather than standing fully upright. Also, unlike the other three statues, Saint Veronica is not made from two primary blocks, but, as Mochi is quoted, from “three great blocks, put together in a most difficult way in which the joins are never seen again.” Mochi’s seamless and ingenious construction from three separate blocks made the dramatic forward lean of the figure possible, speaking to the balance of technical and formal invention in Baroque sculpture. At the left rear of the figure, Mochi carved his signature, indicating through this symbolic counterweight his literal and figurative balancing act in Saint Veronica. Backstory: In 1624, Bernini was at work on the Baldacchino marking the high altar of St. Peter’s, and over the next several years, ideas for housing the basilica’s most prized relics in the crossing piers evolved through discussions with the Pope. The need for altars associated with the relics was strongly felt for liturgical and devotional purposes. While this plan for honoring the relics through sculpted altars remained unchanged, a recognition that the new basilica required a solution more appropriate to the grandeur of the crossing led to the introduction of a new element: colossal marble sculptures.

0 Comments

Where? Second floor, room 846 of the Richelieu wing in the Louvre

When? Between 1626 and 1628 What do you see? A prostitute smiling provocatively. She has half of her breasts exposed. The use of light emphasizes her expression and cleavage. She wears a white linen garment with a salmon-colored bodice on top of it. She has rosy cheeks and looks to her left (our right). It seems that she is seducing a potential client. By 17th- and 21st-century standards, the woman may not be very pretty. She has a somewhat big nose, not a very smooth skin, and her hair is somewhat unkempt. However, her facial expression is so intriguing that this work leaves a lasting impression on those who view the painting. Frans Hals used loose and rough brush strokes for this painting. While Hals is known for his loose brush strokes, in this painting he used them more than in most of his other works. The style used for this work helps to make The Gypsy Girl very memorable. Backstory: Louis La Caze owned this painting in the 19th century. He was a doctor from Paris and an avid art collector. He gave the name The Gypsy Girl to this painting. This title is not very accurate as he did not recognize that Frans Hals actually painted a prostitute (though she may have been a gypsy). La Caze left this painting for the Louvre after his death in 1869, together with 568 other paintings. When the Louvre received the painting, the influential newspaper Gazette des Beaux-Arts praised Hals as the best painter ever. Malle Babbe: This painting is also sometimes referred to as Malle Babbe. However, this name is incorrect as Hals has another painting entitled Malle Babbe. This painting is in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. The confusion can be explained as a popular Dutch song, entitled Malle Babbe, was written in 1970. This song was inspired by the Gypsy Girl. However, the writer of the song, Lennaert Nijgh, mistakenly thought that The Gypsy Girl painting was called Malle Babbe.

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was born in 1582 or 1583 in Antwerp, Belgium, and died in 1666 in Haarlem, The Netherlands. When Hals painted The Gypsy Girl, he was inspired somewhat by the works of Caravaggio. However, Hals differed substantially from Caravaggio as he left out many (distracting) details in his paintings and focused on the composition and the expression of his subjects. This allowed Hals to give his subjects a personality.

While Hals was a popular local painter during his life, his works were largely forgotten after his death. The Impressionist painters rediscovered his work in the 1860s. Artists like Manet and Monet were inspired by the lack of detail, beautiful composition, and the loose brush strokes of Hals. The work of Hals has only gained in popularity since. Some beautiful works of Hals include his series on the four evangelists, of which Saint John the Evangelist is in the Getty Museum, and the Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Fun fact: Radiographic analysis of this painting revealed that Frans Hals initially wanted to paint a less provocative version of this woman. Her breasts were smaller and less exposed. However, Hals decided to make the painting more provocative. This painting shows more cleavage than any other painting by Hals. The open mouth of the woman is also a telltale sign. Decent women from the 17th century would never be depicted with a smile or open mouth in a portrait as that was considered indecent.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster.

Where? Room 254 of the New Hermitage building in the Hermitage Museum

When? 1668-1669 What do you see? Six(!) people in front of an arched doorway. On the left, an old man lovingly embraces a young and bold man who bows his head in humility. This is his son who returned home after a long time. While the father is dressed in beautiful clothes, the son is not. He wears old clothes with holes in it, and his sandals are worn and broken. He still wears the dagger on his belt that he needed to defend himself in the outside world. On the right, at a little distance, is the older son of the old man. Dressed in a red cloak, he has his hands folded while holding a cane. He looks at his younger brother with a mix of disapproval and envy. It is not certain who the other three people in this painting are. The woman in the middle background may be a sister or the mother of the prodigal son. The seated man with a mustache may be an older servant. On the top left, barely visible, is the silhouette of a female servant. Rembrandt uses light to emphasize the important aspects of the painting. The father and son are fully in the light, the older son is partially in the light, and the other people are in the darkness.

Where? Room E204 of the J. Paul Getty Museum

When? 1632 What do you see? The Ancient Roman god Jupiter (Zeus in Greek mythology) is disguised as a beautiful white bull. He just seduced Europa and takes her away on his back into the sea. He has his tail up as an indication that he is happy with the successful abduction. Europa sits on top of the bull, holding a horn with her right hand, and fearfully looks back at her servants on the shore. They are the Virgins of Tyre (where Europa lived as well), with whom Europa was playing before she got abducted. They watch in disbelief how Europa gets abducted. The woman in blue has dropped the flower garland they made for the bull in her lap and raises her hands up in the air. The other woman looks at Europa while folding her hands as if she resigns in Europa’s fate. In the background is the horse carriage with four horses that had brought Europa to the beach. The story of Jupiter and Europa? This story is based on the second book of Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid (Amazon link to Metamorphoses). At the end of the second book, in lines 833 till 875, Ovid describes how Jupiter falls in love with Europa. She was the daughter of a king in an Eastern land. Jupiter asks his son Mercury to go to that land and drive the herd of royal kettle to the beach, where Europa is playing with her servants. Jupiter disguises himself as a tame white bull and puts himself among the royal kettle. Europa recognizes his beauty and starts to play with him. While a bit afraid at first, she eventually climbs on his back, and Jupiter takes that opportunity to walk into the water and escape with her on his back. This story has also inspired other painters. Titian painted The Rape of Europa in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and Jean-François de Troy painted The Abduction of Europa in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Background: This painting is one of only few paintings by Rembrandt in which he included an extensive landscape. The Getty Museum acquired it in 1995 for about $27 million, which was a new record for a Rembrandt painting at that time. They bought it together with another painting by Rembrandt, Daniel and Cyrus before the Idol Bel, which is also still in the Getty Museum.

Who is Europa? A figure in Greek mythology. She was born as the daughter of a king of a land somewhere near current-day Lebanon. She is primarily known by the story on her abduction by Jupiter who brought her to Crete. She was still a virgin before the got abducted.

Jupiter and Europa get three children together: Minos (who will become the king of Crete), Rhadamanthus, and Sarpedon. After their death, these three sons became the judges of the Underworld. The continent of Europe is named after Europa, as Jupiter took her from Asia to this new continent. Also, one of the moons of the planet Jupiter is named after her (many moons of Jupiter are named after lovers of Jupiter). Who is Rembrandt? Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born in Leiden, The Netherlands, in 1610. In 1631, he moved to Amsterdam where he initially ran a very successful painting business. He painted The Abduction of Europe in the year after his arrival in Amsterdam. He stayed there for the rest of his life and died in 1665. During his life, he experienced many challenges, like the death of his wife and children and financial trouble, but he always remained productive. Nowadays, he is considered one of the most famous artists that ever existed. Rembrandt did not paint many mythological paintings during his career. He preferred religious subjects, like Saul and David in the Mauritshuis in The Hague, or portrait paintings of individuals or groups, like he did in his famous The Night Watch in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Fun fact: Rembrandt included some great details in this painting.

Interested in a copy for yourself: Poster or canvas.

Where? Room 96 of the Uffizi Museum

When? 1597 Commissioned by? Cardinal del Monte, who gave it as a gift to Ferdinando I de Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany What do you see? A depiction of the head of Medusa painted on a circular and curved wooden shield. Medusa is a figure described in Greek mythology. With her glance she could turn people who looked at her into stone. Instead of normal hair she has living, venomous snakes on her head. The snakes are watersnakes from the Tiber river as those were the best type of snakes Caravaggio could find nearby. I count at least eight snakes on her head. The blood streams out of her head as she has just been killed by the Greek demigod Perseus. This painting shows the moment that Medusa is looking at the reflective shield that Perseus is holding (which according to the myth actually happened just before she got beheaded). She realizes that her head is separated from her body, but that she is still conscious. You can see this realization by the horror in her eyes. As the painting is created on a shield, Caravaggio’s idea was that this painting actually represents the view of the shield as held by Perseus just after he killed Medusa. It is also interesting to have a closer look at Caravaggio’s use of light and shadow in this painting. Do you see how Caravaggio used these contrasts to show the head of Medusa as a three-dimensional object?

Who is Caravaggio? Michelangelo Merisa da Caravaggio (1571-1610) was trained by Simone Peterzano, who was in turn trained by Titian. He used a realistic painting style, paying attention to both the physical and emotional state of the subjects he painted. He combined this with a beautiful contrast between light and shadow in his paintings. He was a brilliant and unconventional artist.

During his life he received quite some commissions for religious paintings. However, Caravaggio always knew to how add some dark elements to the painting. He liked to use beggars, criminals, and prostitutes as models for his paintings, which would often give unexpected outcomes for familiar biblical scenes. Two beautiful examples of his religious paintings are the Death of the Virgin in the Louvre and The Entombment of Christ in the Vatican Museums.

Who is Medusa? In Greek mythology, Medusa was one of three sisters (Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa) who were often referred to as Gorgons. Both Stheno and Euryale were immortal, but Medusa was not. They were daughters of Phorcys (a sea god) and his sister Ceto (a sea goddess).

According to the Roman poet Ovid, Medusa was a beautiful young woman. However, after Poseidon (the god of the sea) made love to her in Athena’s temple, Athena (the goddess of wisdom and war) changed her beautiful locks into living, venomous snakes (in other mythological stories the three sisters were already born with snakes on their heads). Medusa had a horrific facial expression that could turn people (or according to some, only men) who looked at her into stone. The Greek hero Perseus, a demigod, used a shining shield that he got from the goddess Athena to avoid looking at her directly and succeeded to cut off her head. He used her head as a weapon afterwards as it retained its power to turn people who looked at it into stone. Perseus ultimately gave the head of Medusa to the goddess Athena, who placed the head on her shield (which is what is depicted in this painting). When the head of Medusa was cut off, two creatures arose from Medusa’s body: Pegasus, a winged horse, and Chryasor, a giant with a golden sword. Medusa in art? Medusa has been a popular subject in art. Famous artists have used her story as the inspiration for their artwork. Well known versions include:

Fun fact: Monica Favaro and colleagues published an academic study about the materials that were used in this painting and the evolution of these materials over time.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas (Amazon links).

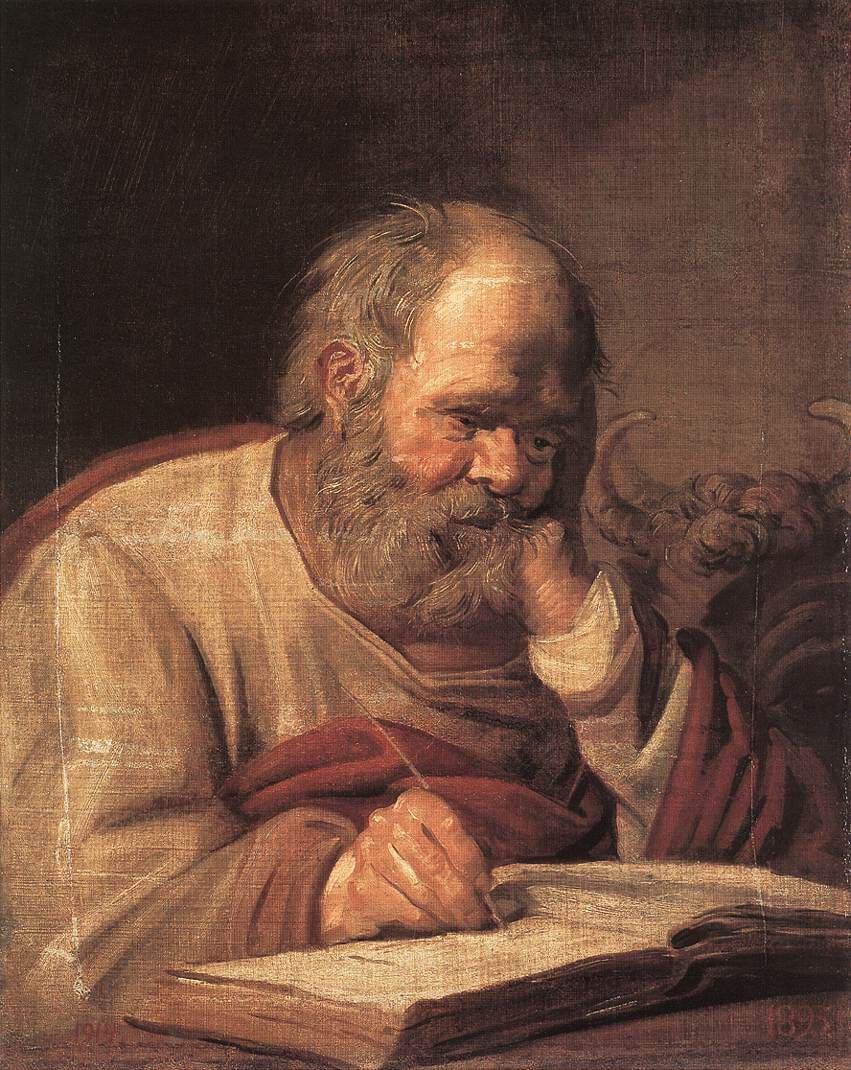

Where? Room E203 of the J. Paul Getty Museum

When? 1625 What do you see? A young Saint John the Evangelist sits in a room. He has red cheeks and wears a red/pink robe with a bold red cloak over his shoulders. He looks up into the light which represents the divine inspiration for the writing of a Biblical book. Saint John holds a quill pen (a pen made of a bird feather) in his right hand, and he has just dipped the pen in the pot with ink on the bottom left. He presses his left hand pressed to his heart to indicate his personal faith that helped him to write the Biblical book. On the right is an eagle which is one of the attributes of Saint John the Evangelist. Frans Hals used broad visible brush strokes to create this painting. His brush strokes are more refined in the face of John. He also makes brilliant use of the light to depict John the Evangelist. Backstory: This work is one of the few religious paintings by Frans Hals. About eighty percent of his works are individual portraits of upper-class people, wedding portraits, or group portraits. The remainder of his work consists mostly of genre paintings. The painting of Saint John the Evangelist is part of a series of four paintings of the apostles, with the other ones being St. Matthew, St. Mark, and St. Luke.

Who is Saint John the Evangelist? The author of the Gospel of John, the fourth book in the New Testament. Before becoming an Apostle of Jesus he was a fisherman. However, it is not certain if the Apostle John is also the author of the Gospel of John, as the author does not clearly identify himself in his writings. He is the only apostle that was not killed because of his faith in Jesus. Some people also attribute the Book of Revelation to him, though this is also a point of debate among scholars.

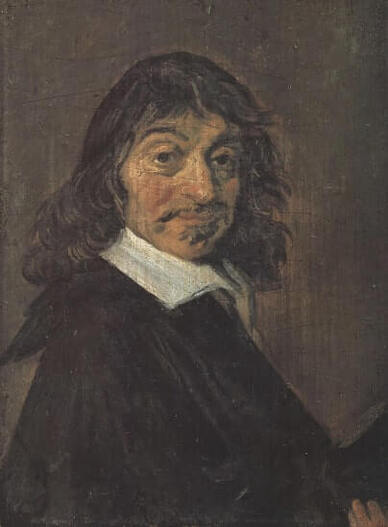

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was born by the end of 1582 (or early 1583) in Antwerp, Belgium, and died in 1666 in Haarlem, The Netherlands. His brother and five of his sons were also painters. Frans Hals is primarily known for his portraits. He had a loose painting style, which means that he used relatively few (but long) brush strokes to depict something. You can often see the brush strokes in his paintings. He painted based on his intuition and was uniquely able to capture the emotions and characteristics of the people he painted. Together with Rembrandt and Johannes Vermeer, Frans Hals is generally considered the best Dutch painter of his time. While living around the same time, the three of them all had unique styles and never met each other in person. Another interesting painting of Hals is the Portrait of René Descartes, the father of modern Western philosophy. This painting is in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen. There are several copies of this painting among which one is in the Louvre in Paris.

Fun fact: This work is part of a series of four paintings in which Frans Hals depicted each of the four evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. All four paintings were lost since 1812 and were only rediscovered during the 20th century.

Cornelis Hofstede de Groot mentioned the four paintings in a catalogue raisonné in 1910, but not much attention was given to these mentions as they seemed to be atypical in Hals’ oeuvre. This changed in 1958, when Irina Linnik, an art historian for Odessa Museum of Western and Eastern Art, rediscovered the paintings of St. Matthew and St. Luke. These two paintings can still be seen in the Odessa Museum of Western and Eastern Art in Odessa. In the 1970s, Claus Grimm identified the painting of St. Mark, which is now in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. The Getty Museum paid $2.9 million for St. John the Evangelist in 1997, when it was rediscovered by Brian Sewell when the painting was brought in for evaluation at the auction house Sotheby’s. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas.

Where? Gallery 213 of the Cleveland Museum of Art

When? 1634 Commissioned by? Tieleman Roosterman and his wife Catharina Brugmans What do you see? The 36-year old Tieleman Roosterman looks at us with a serious and confident expression. He is painted in three-quarter length. Hals pays careful attention in painting his costume, which is not surprising given that Roosterman was an international clothing merchant. Roosterman wears a doublet, which is a short, close-fitting padded jacket. The jacket is decorated in the middle with metal or silver decorations. On top of the doublet, he has a big white ruffled collar. He has slashed sleeves, and on his right sleeve, he has a white cuff with lace edges. He has a glove on his left hand. He wears black breeches, which are a 17th-century type of pants that run just below the knee or till the ankles. In his right hand, he holds a large black hat made of beaver fur (such hats were popular during that time as they could be turned into a variety of shapes). All the items that Roosterman is wearing were very fashionable during his time. Inscription: To the right of Roosterman’s head, Hals included an inscription reading “AETAT SVAE 36 ANO 1634”. This means that Tieleman Roosterman was at the age of 36 at the time of the painting and that it was painted in 1634. Roosterman and his wife, Catharina Brugmans, commissioned Hals to paint a portrait of both of them to celebrate their third wedding anniversary. The Portrait of Catharina Brugmans is in a private collection. When the Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman was auctioned in 1999, it also included a coat of arms and a crest above the inscription. However, by then it was known that the coat of arms contained a pigment that was only available almost a century after Hals painted it. Thus, the coat of arms was removed from the painting by the Cleveland Museum of Art to show its original composition.

Backstory: The Cleveland Museum of Art acquired this painting in 1999 for $12.8 million, a record for a Frans Hals painting at that time. Saint John the Evangelist held the previous record. This work by Frans Hals was sold in 1997 for $2.7 million to the Getty Museum.

Who is Tieleman Roosterman? A rich textile merchant from Haarlem, The Netherlands. He operated internationally and specialized in fine linen and silk. He was born in 1598, married in 1631, and died in 1673, all in Haarlem. Together with his wife, he baptized ten children. Tieleman Roosterman is probably also the model for The Laughing Cavalier painted in 1624 by Frans Hals. This painting is in the Wallace Collection in London.

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was born at the end of 1582 (or early 1583) in Antwerp, Belgium, and died in 1666 in Haarlem, The Netherlands. He painted many portraits and was a true specialist in characterizing his subjects. At the beginning of his career he created more colorful paintings but when he got older the colors he used became darker. Many artists (including Van Gogh) admired the many shades of a single color that he used in his works, and the current painting of Tieleman Roosterman is already a good example of Hals using many shades of black.

Fun fact: This painting was sold in 1999 to the Cleveland Museum of Art by the Austrian branch of the Rothschild family. In 1999, the Austrian government returned many items to the Rothschild family after the Nazis seized these items 61 years earlier. Before 1999, most items were on display in Austrian museums. After their return, the family decided to put many of the items up for sale because their houses were not big enough to properly display all the items. The painting of Tieleman Roosterman was sold with two other paintings by Hals and many other historical items at the auction house Christie’s in London. Interestingly, among the bidders for the items in the collection were several members of the other branches of the Rothschild family (they form a large and very wealthy family with branches all over Europe). It was reported that members of the French and British branch bought some of the items during the auction. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas.

Where? Room 90 of the Uffizi Museum

When? c. 1620 Commissioned by? Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo ll De’ Medici. The Grand Duke died in 1621, shortly after the painting was completed. It was only with the help of Artemisia’s friend, Galileo Galilei, that she managed to extract the payment for the agreed sum for the canvas. Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 146.5 x 108.0 cm. What do you see? The moment that Judith, with the help of her maidservant Abra, is beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes. Unlike many other artists, Artemisia Gentileschi chose to portray the scene at its zenith. It is the most powerful and horrific moment to imagine. Holofernes still struggles, his right hand fruitlessly trying to jab at Abra. His soon-to-be lifeless forearm comes to rest in the crook of her shoulder. His right knee is bent in a futile attempt to escape. Abra’s arms press downwards with great strain to hold Holofernes’ left arm down and still. The concentration and intense focus on what she is doing registers in her facial expression. Abra’s hair is covered with a white turban, and she wears a blue dress. The white sheet and the red coverlet lay rumpled over the commander. The sword's thrust in Judith’s hand produces blood spurts that reach Abra’s arm and Judith’s dress and body. Blood seeps over the bed and down the edges as life drains from him. His face is already losing the expression that gives it life, and it will soon be tucked into the food bag, wrapped in the bejeweled cloth that will be triumphantly removed once the two Jewish women return to their hometown Bethulia. Judith strains! The force she is expending is visible as she clutches the hair on Holofernes head and presses his head into the mattress with her left arm. Her right arm twists and rotates as the sword makes its cut. She uses the sword of Holofernes. The edge of the cross on the sword digs into the skin of his upper left arm, and we can see the pressure on it. Sleeves rolled up on both the women suggest they had some time to prepare, at least a bit, beforehand. He must have been quite drunk. The gown that Judith is wearing attests to the seduction that was her purpose. The low cut of the dress exposes her breasts and must have been enticing to Holofernes. Her hair is coiffed in the style of a noblewoman, uncovered, revealing its charms. She apparently was perfumed and prepared to seduce. Artemisia has painted one of her own bracelets on Judith’s arm in this second version of the scene. One cameo depicts Artemis, the ancient goddess of chastity and the hunt. It raises the question of whether Artemisia identified with this goddess? The textured walls of the tent provide a dark backdrop that not only frames the scene but also produces the contrast between light and dark that intensifies the actions of each individual. The light source comes from the left. The composition of the three figures focuses the viewer’s attention on the central part of the canvas.

Where? Gallery 632 of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

When? Around 1662 What do you see? A young woman opens a leaded window with her right hand, and she holds a water pitcher in her left hand. She wears a blue dress with a blue and gold-like vest (called a bodice) on top of it. She also wears a white collar and an equally white linen head covering. The silver water pitcher is standing on a silver basin. The table is covered with an expensive and colorful tablecloth with flower patterns. On the right of the table is a box with a blue ribbon and a pearl necklace. Behind the table is a chair with a carved lion on top of it. A blue cloth hangs over the chair. On the top right hangs a map of the seventeen provinces of Hapsburg Netherlands in the 17th century (interestingly, the west of Hapsburg Netherlands is shown on the top, and the north is shown on the right). The walls in this room are somewhat off-white (which is clear when seen in contrast to the head cover of the woman) and we can see the effects of the sunlight. We can recognize different shadows on the wall left of the woman, but we can, for example, also observe the shadows on the nails in the chair. The light in this painting is gently changing the colors of the various objects. It is not entirely clear what the woman is doing. It is possible that she wants to water some of the flowers that are outside the window or she may want to clean the window. Note that the window is the same as the left window in The Music Lesson by Vermeer.

Backstory: This painting is also known as Woman with a Water Jug. It is a genre painting depicting an everyday scene from the life of the 17th-century middle class in The Netherlands.

In 1887, Henry Marquand acquired this painting for $800 and later donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This was the first Vermeer painting to come to the United States. Balance and peacefulness: As in many other paintings of Vermeer, this painting shows a balanced composition which results in a very peaceful domestic scene. First, Vermeer achieves this by using a limited number of colors in this painting. He mainly uses the three primary colors: blue, red, and yellow. Second, Vermeer took many months to complete a single painting, and he added and removed various elements over that period to create the harmony that we see in this final version. For example, based on infrared technology, we know that Vermeer originally included another chair in the left foreground and the map on the wall was bigger and placed much more to the left. However, this created a more chaotic scene, and Vermeer proceeded to update the painting (check here for a virtual reconstruction of the earlier version of this painting). While removing the chair may not have been that much work, completely redoing the map on the wall on a different location was a lot of work and explains why Vermeer took such a long time to complete a painting (and the map turns out to be very accurate). Who is Vermeer? Johannes Vermeer was born in Delft, The Netherlands, in 1631 and died there in 1675. His father owned a tavern and was an art dealer. Early in his career, Vermeer got some inspiration from works by the followers of Caravaggio and especially their use of light. Vermeer developed his own style and primarily focused on genre paintings. The domestic scenes that he portrayed have become famous through their realism and excellent use of light and shadow. Besides the current painting, other examples that illustrate his brilliance are The Milkmaid in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and Girl with a Pearl Earring in the Mauritshuis in The Hague. The work of Vermeer was certainly appreciated during his career, but after his death, there was a period of almost two hundred years during which his work was largely forgotten or attributed to other better-known painters. In the second half of the 19th century, his work was rediscovered and quite some well-known paintings were attributed to Vermeer.

Fun fact: As you can see in the paintings above, Vermeer used a lot of blue in his paintings. For this he used the pigment ultramarine (which is a natural pigment made from lapis lazuli). The use of this pigment differentiated him from his contemporaries as lapis lazuli was very expensive.

Most other painters used the much cheaper azurite to create blue. Lapis Lazuli is a rock with a deep blue color, and this rock was not available in Europe but had to come from countries like Afghanistan. Ultramarine is created by grinding lapis lazuli into powder and combining it with a drying oil. Titian is another well-known artist who often used ultramarine. During the Renaissance, ultramarine was primarily used to paint the robe of the Virgin Mary. The ultramarine pigment remained very expensive until 1826 when synthetic varieties of ultramarine became available. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster

Where? Gallery 45 of the National Gallery of Art

When? 1614-1618 Commissioned by? Unknown, but possibly Rubens created this as a showpiece for his studio. What do you see? Daniel is in the lions’ den surrounded by life-size lions. He sits on a colorful red cloth and has a white cloth wrapped around him. His body is tense with his legs crossed and his arms together. Given the light in the background, it seems that this painting captures the moment in the morning after Daniel has spent a full night in the den. Daniel is praying with his hands folded and he is looking up into the air. Some lions are sleeping, others are looking straight at us, and others are roaring or growling. There are nine lions and lionesses. In the foreground are the bones and a skull as evidence that the lions have already eaten some people. However, a young Daniel is sitting alive in the middle of the den. Notice that according to the Biblical story, Daniel was much older when he was thrown into the lions’ den, probably around 80 years old.

The painting is based on the Biblical story in the Book of Daniel, chapter 6. In short, Daniel is a high-level administrator for the Persian king Darius. He is doing so well that Darius wants to promote Daniel to be in charge of the full kingdom. The other administrators hatch a plan to trap Daniel. They convince Darius to issue a decree that in the next 30 days no one could pray to any god or human other than king Darius. As Daniel continues to pray to his God, he is sentenced to be thrown into the lions' den which nobody could survive. Darius says to Daniel before he is thrown in the den: “May your God, whom you serve continually, rescue you!” A big stone then covers the den.

The next morning Darius checks on Daniel and finds him still alive without any scratch. After that, Darius decided to throw all the administrators and their families in the lions’ den next, and they were all killed before they even reached the floor. Symbolism: The message of this painting reflects the message from the Biblical story of Daniel in the lions’ den: If you trust in God, he will protect you from no matter what, even from a pride of hungry lions. This story also symbolizes the resurrection of Jesus from the dead. The lions symbolize the powerful rulers on earth. Daniel is praying and looking upwards to Heaven, which symbolizes his faith in God. The skull in the foreground refers to Golgotha, the place where Jesus was crucified. The red cloth refers to the blood of Jesus.

Who is Rubens? Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) is a Flemish painter. He was born in Siegen, which is now in Germany, and died in Antwerp, Belgium. Together with Caravaggio, Rubens was one of the most well-known painters of his time. He used a Baroque style of painting.

In 1600, Rubens traveled to Italy, where he stayed for eight years. He spent time in Venice, Florence, and Rome and got inspired by the works of artists like Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian. After this period he moved back to Belgium, where he set up his studio. Together with his many students and apprentices, he produced a very large number of paintings during his life. Fun fact: Rubens liked to include wild animals in his paintings and was often asked to paint hunting scenes. As he was one of the most dramatic painters of his time, he was perfectly suited to create some crazy hunting scenes. He could study most of these wild animals in the menageries that some of the richest people liked to have around that time. One thing he had to change, however, was to paint the animals like they would behave in the wild as opposed to the often tamed animals he observed in the menageries. In his different paintings, he included wild animals, such as bears, crocodiles, foxes, hippos, lions, tigers, and wolfs. These hunting scenes were always on commission, and they were a great way for Rubens to earn money. See, for example, the painting of The Tiger Hunt by Rubens. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us