|

Where? The Crossing of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.

When? Carved between 1629 and 1640. Commissioned by? Pope Urban VIII and created under the direction of Gianlorenzo Bernini. What do you see? The statue of Saint Veronica is of colossal size, measuring 5 meters (almost 16.5 feet) tall. The choice of marble colossi for the crossing bears the influence of the Pope, as the colossus was a sculptural type considered one of the most impressive accomplishments of the ancients and was also closely associated with Michelangelo. In fact, the earliest records related to the effort to obtain marble for the four crossing statues indicate that it was initially hoped that each statue would be carved from a single colossal block, similar to Michelangelo’s David. However, this was not the case as each figure was made from multiple blocks. Nevertheless, Saint Veronica is only centimeters short of Michelangelo’s David, though one might not suspect that due to the disorienting scale of St. Peter’s Basilica. At five meters high, Mochi’s Saint Veronica is half a meter higher than the three other colossi, despite the fact that it is the only figure that leans forward rather than standing fully upright. Also, unlike the other three statues, Saint Veronica is not made from two primary blocks, but, as Mochi is quoted, from “three great blocks, put together in a most difficult way in which the joins are never seen again.” Mochi’s seamless and ingenious construction from three separate blocks made the dramatic forward lean of the figure possible, speaking to the balance of technical and formal invention in Baroque sculpture. At the left rear of the figure, Mochi carved his signature, indicating through this symbolic counterweight his literal and figurative balancing act in Saint Veronica. Backstory: In 1624, Bernini was at work on the Baldacchino marking the high altar of St. Peter’s, and over the next several years, ideas for housing the basilica’s most prized relics in the crossing piers evolved through discussions with the Pope. The need for altars associated with the relics was strongly felt for liturgical and devotional purposes. While this plan for honoring the relics through sculpted altars remained unchanged, a recognition that the new basilica required a solution more appropriate to the grandeur of the crossing led to the introduction of a new element: colossal marble sculptures.  Angel of Annunciation (1603–1609) by Francesco Mochi Angel of Annunciation (1603–1609) by Francesco Mochi

Who is Saint Veronica? According to church tradition, as Jesus was carrying the cross to Calvary, Veronica gave him her veil to wipe away his blood and sweat, and the cloth subsequently captured an image of the Holy Face. Honoring this relic, Mochi’s marble sculpture is one of four works in the crossing of St. Peter’s Basilica created under the direction of sculptor Gianlorenzo Bernini, the other three being François Duquesnoy’s Saint Andrew, Bernini’s Saint Longinus, and Andrea Bolgi’s St Helena.

Who is Francesco Mochi? Francesco Mochi was an Italian sculptor born in 1580 whose works pioneered the Baroque style of sculpture. Before the commission for the crossing of St. Peter’s, Mochi was a renowned carver of bronze equestrian statues. The sculptor had a rather tragic end to his life and career, for as the young Bernini began to dominate the Baroque style, Mochi grew extremely bitter, to the extent that he forsook all of his Baroque experiments for more linear and static sculptures. Though this post focuses on the innovative genius of Francesco Mochi, it is necessary to acknowledge that Gianlorenzo Bernini was the leading sculptor of this period and far more widely credited with creating the Baroque style of sculpture. Symbolism: After the viewer digests the overwhelming size of the sculpture, one of the most striking and symbolically rich details comes into focus: Mochi’s unyielding, knife-edged drapery folds. Such experimental use of drapery did not please a critical audience increasingly enthralled by Bernini. Art critic Valentino Martinelli championed Mochi as Bernini’s great rival, yet the scholar condemned Saint Veronica as ‘a great hysteric launched against the wind.’ The 18th-century critic Giovanni Battista Passeri famously objected to the figure’s movement. Passeri is also quoted with a critical observation of Mochi, saying, “Francesco Mochi, who was born in the state of Florence, always wanted to show himself a rigorous imitator of the Florentine manner.” This sentiment speaks to the unique relationship between Mochi and Pope Urban VIII, a proud Florentine himself, and it also unveils the rich Florentine motifs that influenced Mochi’s sculpture. This theme is illustrated in Mochi’s first significant commission, the Angel of the Annunciation, which finds its closest analogies in 16th-century Florentine painting. The fact that Mochi chose to represent the angel in flight rather than standing or kneeling, as would have been expected according to the iconography of the Annunciation, suggests his pursuit of the terrain of painting. It is worth noting how this theme is also found in Gianlorenzo Bernini’s ambitious fusion with painting. Looking at the draperies of Mochi’s Angel, one can see the precise and deeply undercut carvings, which register the angel’s descent through the air. At its thinnest points, the marble drapery extending from the Angel’s right side allows light to shine through. This brilliant drapery carving would become a hallmark of Mochi’s style and the key marker of his modernity, as he essentially reconceived figural sculpture as the manipulation of draperies rather than nude bodies.

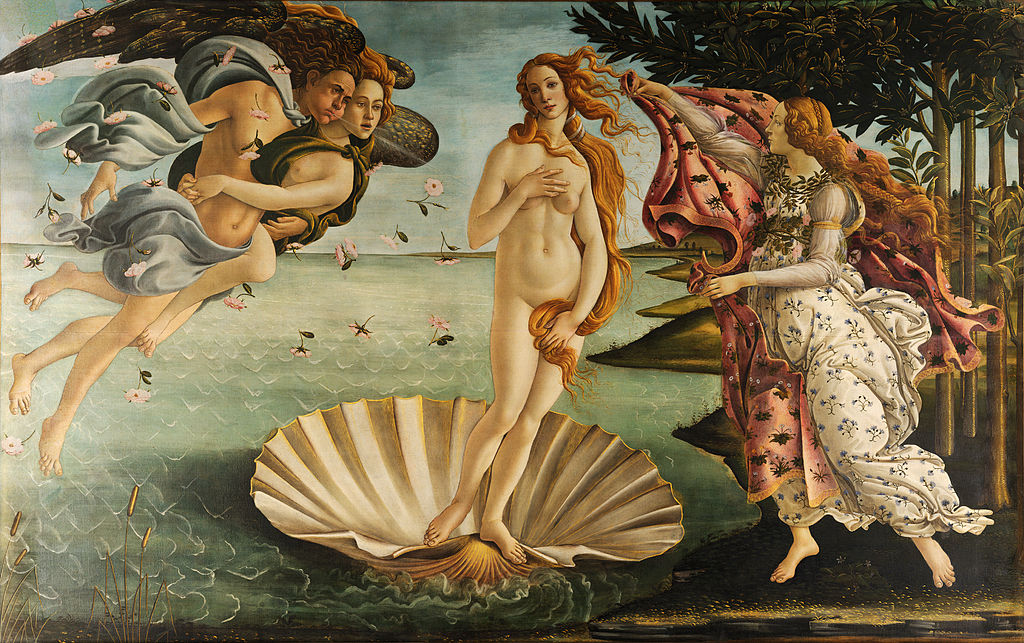

Mochi also reconceived the figure of Veronica as a reflection of the ancient type of the bacchante, or Nympha, a famous motif in Florentine painting, again aligning himself with the “Florentine manner.” In the figure of the Nympha, the revelation of the body beneath the billowing garments was combined with the tension of the drapery’s movements, two of Mochi’s primary stylistic traits. In the statue, Mochi relied heavily on the role of the Nympha in the Florentine tradition, who had been frequently adapted to the role of the impassioned religious mourner, an apt symbol for the Saint Veronica, whose agitated drapery registers the frenzy of grief. She was also a form of virtuosic display, famously featured in the works of Sandro Botticelli.

The Nympha in The Birth of Venus shows clear similarities to Saint Veronica, specifically to how in Florence, the Nympha was often a bringer or bearer. In the Birth of Venus, Flora is poised to bear and wrap a cloak around Venus to cover her nudity, while Saint Veronica is actively bringing the veil into the crossing. Because the complexity and elevation of the Nympha’s drapery were more readily rendered in painting or relief than sculpture, Mochi had to essentially invent their sculptural style. Initially, he created early models of the figure to be freestanding, in-the-round. This would almost encourage viewers to walk around the saint and intertwine themselves with the figure, as if they are an extension of the drapery. While these unique arrangements attempted to engage viewers in a dynamic revelation, they resulted in limited viewpoints of the image on the veil, and it was decided that these early models did not give enough emphasis to the represented relic. However, Mochi still infused the final sculpture with subtle references to these unique designs.

Mochi vs Bernini: The sculptural experimentation in the crossing was not limited to Mochi’s extraordinary figure but included and was often dominated by Bernini’s Baroque vision. It is essential to compare Mochi’s vibrant drapery to that of Bernini’s Saint Longinus. This sculpture represents the Roman centurion at the moment of his conversion, when, after piercing the side of the crucified Christ with his lance, he recognized Christ’s divinity. In the figure, Longinus is engulfed by a long, cloak-like mantle arranged in a forceful pattern of folds that no longer performs drapery’s traditional function of explaining the body beneath, but instead functions freely and expressively on its own. The energy, echoed in the figure’s electrified hair, is channeled through the impossibly long edge of the mantle on Longinus’s right that carries over to the enormous knot at his left hip. The animated drapery defies gravity, signaling the presence of the supernatural and evoking Longinus’s sudden experience of the divine. Ultimately, this is a radical break with the Renaissance tradition, as Bernini’s newly autonomous drapery is no longer subordinated to the body but shatters the Renaissance language of the body. Not only is the saint’s body obscured, but the overall figure is subject to the expressive effect of the drapery. Below the mantle, only the calves are visible, and above it, only the upper torso emerges from the drapery, which extends to the top of the ribcage. The body between these areas can only be imagined, and even so, with great difficulty, as the mantle’s folds bewilder the measurement of the waist, the proportions of which are impossibly long and narrow. The bend in the saint’s left arm is similarly bewildered by the wrapping mantle, whose upper folds emphasize the energy running from the straight right arm directly to the left forearm, sacrificing anatomical clarity to increase the expressiveness of the drapery and resulting gesture. Bernini prioritized the saint’s tense extremities and spiritual energy over a more anatomically detailed figure. Mochi’s Saint Veronica and Bernini’s Saint Longinus are relatively similar in the way that their drapery is expressively free to move at will; however, when Bernini broke with the Renaissance language of the body, he fundamentally altered the Renaissance conception of sculpture, which was essential to Mochi’s style and pursuit of the “Florentine manner.” Mochi and Bernini’s reconception of freestanding sculpture in relation to painting are equally effective, just in vastly different ways.  St. Martha (1609–1621) by Francesco Mochi, St. Martha (1609–1621) by Francesco Mochi,

Bernini furthered this expression in the striated pattern of chisel marks that cover all the surfaces on Saint Longinus. The marks are understood as an optical device intended to enhance the legibility of the colossal forms by diffusing the distribution of light and dark. Similar to his sacrifice of anatomical proportions, Bernini sacrifices the integrity of the sculpture’s surface for optical effect. Chisel marks remind the viewer that the sculpture is only a statue, even suggesting the similarity between the striations and a painting’s brushstrokes. Mochi openly rejected such optical surface effects as fundamentally foreign to sculpture. This again conveys the contradictory Baroque vision held by Mochi and Bernini, both attempting to bring sacred sculpture closer to painting.

Mochi vs the Niche: Saint Veronica is unique to the other figures in the crossing in that she rushes forward from the niche, especially since Veronica was conventionally portrayed statically. Examining the origin and significance of Mochi’s relationship with the niche is essential. In his Saint Martha from the Barberini Chapel, the tension between the figure’s implicit height and the niche space is emphasized to the beholder through Mochi’s design of the saint’s pose. As Martha stands unsteadily on the twisting dragon whose body rises on an upward diagonal across the niche, the saint’s action of reaching down brings her head and right arm fully outside the niche space. Because the saint is shown in this action of bending over, the viewer is made aware that when she rises upright, the niche will be too small to hold her. A similar theme is found in Saint Veronica. Mochi’s idea of having Veronica rush forward with the veil was unprecedented in her visual tradition. The decision to interpret the saint through a running figure of the Nympha and at a colossal scale had never been attempted, as the statics for such a figure posed extreme challenges. Mochi’s final marble is portrayed in an unstable posture, with both feet raised from the ground and a pronounced forward lean that breaks the boundary of the niche. This again emphasizes Mochi’s rejection of the niche in a way that almost suggests that the sculpture herself is demanding to be seen in-the-round.

Figura Serpentinata: Mochi’s risky, virtuosic carving, and expressive drapery are critical markers of his modernity and the distance between Michelangelo’s time and his own. Michelangelo’s archetypal figura serpentinata famously exalted the expressive power of the nude, visibly counterbalancing artful serpentine torsion with an active play of muscles under the skin, further circumscribing the role of drapery. Meanwhile, Mochi experimented with innovative ways to expand the expressive potential of drapery. It is interesting to compare the similarities of Mochi’s Saint Veronica with a 19th-century modern dance by Loïe Fuller, called the Serpentine Dance, an apt title to juxtapose with Michelangelo’s Serpentine Figure.

A New York City newspaper reviewer first described the dance: “Suddenly the stage is darkened, and Loïe Fuller appears in a white light which makes her radiant and a white robe which surrounds her like a cloud. She floats around the stage, her figure now revealed, concealed by the exquisite drapery which takes forms of its own and seems instinct with her life.” The likeness between Mochi’s sculpture and the Serpentine Dance is undeniable, to the extent that the New York City newspaper reviewer could be standing in front of the Saint Veronica. If Bernini’s imitatio Buonarroti, or his imitation of Michelangelo’s Serpentine Figure, is a hallmark of his style, then Mochi’s Serpentine Dance is its Baroque challenger.

One could even argue that Saint Veronica’s twisting dance more fluently responds to Bernini’s Baldachin and its twisting columns than the other sculptures in the crossing. Mochi’s Baroque is not contradictory but complementary to Bernini’s vision, unveiling Veronica’s freestandingness in a niche like its theatre-in-the-round. Fun Fact: Mochi constantly expressed his discontent with Bernini, who designed the entire crossing, as their animosity toward one another was long-standing. This enmity speaks to the motive for Mochi insisting that Saint Veronica would not require a weekly dusting because it was completely finished and there was nowhere for dust to lodge, as opposed to the chisel marks of Bernini’s Saint Longinus. Mochi’s digs at Bernini continued into an exchange about how the Saint Veronica was set, in which Bernini had asked contemptuously where the wind was coming from that was blowing the draperies against her body, to which Mochi responded, “from the cracks you have made in the dome.” Despite all the tension between Mochi and Bernini, it is ironic that in the many reconfigurations of the crossing, Mochi’s sculpture, in all of its movement, was the only statue whose position remained unchanged.

Written by Luke McLemore

References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us