|

Where? Many museums own a woodblock print of this work, including the Art Institute of Chicago, British Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, but this work is usually not on permanent display.

When? 1829-1832 What do you see? A giant wave off the shore of the Kanagawa prefecture dwarves three boats — one in the foreground, one in the middle ground, and one in the background. The perfect curves of the wave’s form the relentless rocking feeling that terrifies the occupants and rowers on the tiny boats. Perhaps they are fishermen. Above them, it’s raining seafoam, represented with delicate white specks and claw-like crests. In the distance, standing before a grey haze is Japan’s great Mount Fuji. The mountain balances the downward curve of the wave while emphasizing the enormousness of the wave. Backstory: Hokusai created The Great Wave as part of a series of landscapes titled Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjurokkei). Mount Fuji, a sacred spiritual site in Japanese culture, appears in every print in the series, but is not conspicuous in every piece. Often, it appears in the background of the prints such as in the case of The Great Wave off Kanagawa. The scenes that Hokusai created surrounding Mount Fuji were drastically different, varying in season, setting, and overall atmosphere. There are serene scenes such as Inume Pass in the Kai Province, lonesome scenes such as Tama River in Musashi Province, and intense scenes like The Great Wave. Showing the important landmark from several locations, Hokusai emphasized the permanence and stillness of Mount Fuji. No matter the condition of life, the mountain would remain exactly where it stands.

Ukiyo-e: Ukiyo-e, meaning “pictures of the floating world,” was the major art style of the Edo period, which was popular between 1603 and 1868 in Japan. During this time, under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, ideas like sensuality and tranquility were promoted, prompting the creation of a genre of art depicting leisurely daily life.

Ukiyo-e began on silk screens depicting life in the urban sphere. The genre blew up when ukiyo-e artists began creating woodblock prints. The medium allowed for mass production and mass consumption. These images of courtesans, kabuki, daily activity, and nature soon spread to Europe once Japan opened its ports in 1853 spurring the Impressionist movement and inspiring artists such as Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Who is Hokusai? Katsushika Hokusai was a prominent printmaker and painter of the Edo period. He was born in 1760 and died in 1849 after a long career of art making. When he was 19 years old, he studied under Katsukawa Shunsho who gave him the skills to begin producing his own unique artworks when he was 20. After a dispute with his teacher, Hokusai ended his studies and began making sketches for woodblock prints that would be turned into picture calendars alongside his own prints of portraits of women. Soon he became a major player in the ukiyo-e movement, competing with Hiroshige and creating illustrations and paintings for popular fiction books. A practicing Buddhist, Hokusai paid special attention to nature, and, in his own time, he produced many landscape paintings and prints including Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji in which his unique style became more prominent. He also painted birds and flowers with bright, intense colors. Hokusai was careful to depict daily life without any exaggerations but with great beauty. Towards the end of his life, Hokusai grew weak in both his health and skill. Nonetheless, before his death at the age of 89, Hokusai created numerous works depicting mystical images such as demons and dragons, a change of pace from his typically realist style. Fun fact: French composer Claude Debussy is said to have been influenced by Hokusai. When Japan opened its ports in 1853, the japonisme movement took over Europe. People quickly got their hands on Japanese goods like furniture and artwork that they would use to decorate their homes. As a student in Rome, Debussy frequently purchased Japanese goods. One of the prints that he discovered and hung on the walls of his home in Paris was The Great Wave which is said to have inspired his masterpiece, La Mer.

0 Comments

Where?

What do you see? A young dancer of fourteen years old is shown at 70 percent of her real size (the sculpture is a bit taller than 3 foot or about 1 meter). She seems relaxed and is standing in ballet’s fourth position (there are seven positions for the feet in ballet, and the ballerina here has her feet in open fourth position – about 12 inches apart and facing different directions). The girl is sculpted realistically and Degas intends to show the hard life of a ballet dancer and what it does to her body. Her back leg supports most of her weight. She has thin legs and arms, holds her arms behind her back, and has her hands clasped together. She confidently holds up her chin, pushes her shoulders back, and her eyes are half closed. She wears ballet shoes, a real tutu made of tarlatan, and a gold-colored bodice (a vest) made of linen. The girl also wears a real ribbon in her plaited hair. Degas used real hair for this sculpture, which he covered in wax.

Copies: The National Gallery of Art holds two statues (the original wax statue and a bronze casting) of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen as well as two nude studies for this statue. When Degas died, about 150 statues were found in his studio of which only one of the versions in the National Gallery of Art had been shown to the public at an exhibition. Many of these statues were in bad shape, but about half of these statues were repaired after his death. The National Gallery of Art has many of these original statues.

The surviving family of Degas decided to create about 22 bronze casts of these statues. Because of this, nowadays, bronze copies of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen can be found in many other locations besides the ones mentioned on the top. For example, the statue is also in the the Art Institute of Chicago, Harvard Art Museums, Metropolitan Museum of Art (currently not on view), and the Norton Simon Museum. One of the bronze copies of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen was sold in 2009 for $19 million.

Who is Degas? Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas (1834-1917) was born in Paris. Whereas he spent most of his life in Paris, he also lived for three years in Italy and spent time in Florence, Naples, and Rome. He started as a more traditional painter by creating historical stories and portraits, but during the 1860s he changed his style and became one of the founders of Impressionism, together with artists like Cézanne, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, and Renoir.

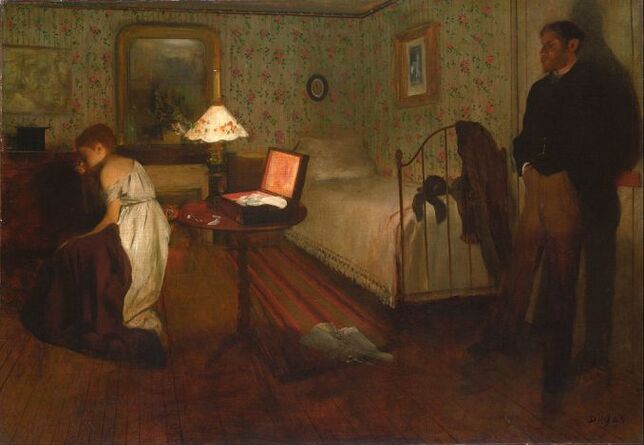

Later on, he changed his focus and started to paint scenes from everyday life with a particular interest in dancers, theater, and horse racing. He moved on to focus on more realistic paintings, and one such example is Interior in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He made statues mainly as training to understand the anatomy and movements of people.

Fun fact: When Degas showed this sculpture at an Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1881, many people did not like it at all. For example, some people called the sculpture a monkey. It also did not help that the sculpture was on display in a glass vitrine. Sculptures typically were idealized versions of well-known people created in marble. Instead, Degas created an unknown young girl from Paris, and the girl did not look at all like a goddess. On top of that, he created this sculpture from beeswax and he added objects like a tutu to the statue. Because of the negative reactions Degas got, he removed the statue from the exhibition and stored it in his studio until his death.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Canvas or statue (Amazon links).  Original version of Self Portrait in a Straw Hat (1782) Original version of Self Portrait in a Straw Hat (1782)

Where? Room 33 of the National Gallery in London

When? 1782 Medium and size: Oil on canvas, 97.8 × 70.5 cm. What do you see? A self-portrait of the 27-year old Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. She painted herself standing outside, wearing a straw hat with an ostrich feather and a garland of wildflowers. And she holds a palette and seven brushes in her left hand. She portrayed herself as an independent and emancipated woman, traits that helped her to become a successful artist in a male-dominated art world. Many other young ladies would have worn a corset, a wig, and a lot of make-up. Instead, Vigée Le Brun portrays herself in a fashionable, pink cotton dress, a black shawl, a straw hat, a pair of earrings, and her own hair. Vigée Le Brun paid particularly careful attention to the impact of two light sources, the sunlight and the daylight. The impact of the sunlight is apparent when looking at how she painted her eyes in the shadow of the straw hat. The result is that the viewer is naturally directed to look at her neck and chest. Backstory: The painting in the National Gallery is actually a copy of a version she made earlier in 1782 and exhibited at the Paris Salon. The original painting is in a Swiss private collection and only a low-resolution image of it is available. The self-portrait of Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun was inspired by the Portrait of Susanna Lunden (c. 1622-1625) by Peter Paul Rubens, which is also part of the collection of the National Gallery. In 1782, during her travels with her husband, she came across Rubens’ portrait in Antwerp. She was particularly impressed by the way Rubens simultaneously incorporated the effects of both natural daylight and sunlight. She immediately started to apply these ideas to her own portrait. After she returned to Paris, she created a second version of this painting, which is the one in the National Gallery today. The same year she also painted the Portrait of Yolande-Martine-Gabrielle de Polastron, Duchess of Polignac, which has a quite similar composition.

Where? Room 27 of the National Gallery in London

When? c. 1513 Medium and size: Oil on panel, 62.4 × 45.5 cm. What do you see? It shows a portrait of a grotesque woman in luxurious clothes. Her face is somewhat malformed due to her suffering from Paget’s Disease. Massys did not try to idealize her, which is also evident by the wart on her cheek. The woman, however, is dressed in luxurious clothes, including a beautiful brooch on top of her headgear and several rings on her hands. Her outfit would have been fashionable some decades earlier, but by the time this was painted, it would be out of fashion. The painting is a pendant to the portrait of An Old Man, which Massys painted in the same year. The woman is depicted as a temptress, which Massys expressed via various clues. First, she holds a rosebud in her right hand, a flower with sexual connotations. Second, she shows a fair amount of cleavage, which would be considered quite scandalous. Third, her headgear decorated with roses, also known as a escoffion, is in the form of a heart shape, although it may simultaneously be interpreted as a pair of horns.

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

Where? The Courtauld Institute of Art in London

When? 1896 Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 64.0 x 81.3 cm. What do you see? A view of Lake Annecy and the Chateau de Duingt, situated in the French Alps, not far from the town of Annecy. The medieval fortress has been there since the 11th century. The view is from the opposite shore over the lake toward the castle. A large tree provides a frame on the left. The tree trunk disappears at the top edge, and the branches and boughs of the tree overhang the upper edge of the painting, their diagonal brushstrokes complimenting the background mountains and framing the view. The castle is situated at the center, with the lake in front and the mountains stretching into the distance behind the partially hidden buildings. Diagonal brushstrokes going in opposing directions create height and depth in the mountains. Highlights of rust, ochre, blues, and greens take the viewer deeper into the hills and valleys. The emerald/blue water is calming, with elongated reflections created with the edge of a palette knife. The light source comes from the left of the artwork and focuses attention on the reflections, tree trunk, and buildings. The contrast of the dark on the opposite side of the highlighting accentuates the importance of the objects in the painting. It is a peaceful scene, yet the composition and the colorings are somewhat startling at first glance. However, it is also a stirring work that asks the viewer to look harder.

Where: Room 15 of Level 0 of the British Museum

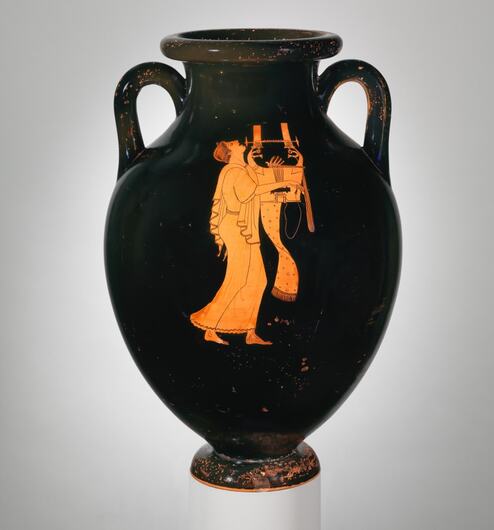

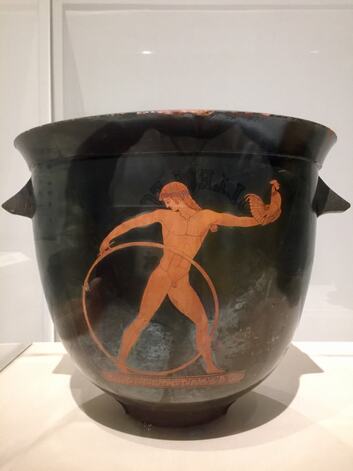

When: Probably between 490 BC and 460 BC What do you see? A monumental vase with two mythological scenes painted on the upper part, the neck. The vase is a masterpiece of the red-figure technique and one of the iconic examples of Athenian pottery. The shape of this vase is called a volute krater (named after the spiral handles resembling the volutes of the Ionian columns).

Background: This vase is one of the early works of the Berlin Painter. Carol Moon Cardon situates it in the second group of vases from his early period, falling between 500-490 B.C. The timeframes are often tentative, depending on the source or criteria by which scholars assign them. More generally, its place in art history falls into the Late Archaic period (circa 500 to 470 B.C.) There are four preserved volute kraters by the Berlin Painter, all in the red-figure technique. The London krater is unique for a variety of reasons; its architectural design resembling the temple is among the most prominent of those. The fact that the painter decided to leave the entire belly of the vase black while placing the narrative and ornamentation on its extremes speaks of his highly sophisticated approach to design and the interpretative role he attached to imagery.

Red-figure technique: The red-figure painting technique appeared in Athens around 520 B.C. in what is known as the Pioneers’ Group—possibly the longest lasting and most influential red-figure workshop known. The Berlin Painter was possibly the student of one of the three most important of the Pioneers, Phintias. Prior to that, until about the second half of the sixth century B.C., the world of the vase painting was dominated by the black-figure technique.

The red-figure technique was actually simpler than the black-figure technique. The main principle in both was the skillful regulation of the flame and oxygen flow through the oven where the vases were fired to assure the proper oxidization of iron, which, in turn, allowed the painter to achieve the desired color. The black-figure technique rested, in principle, on adding varnish to the pre-contoured shapes on the surface of the vase to create fully developed objects and figures, which turned black upon firing; the red-figure technique was the reversal of the process. Who is the Berlin Painter? Very little is known about the Berlin Painter in terms of the biographical information. It was not common for the vase painters to sign their names at that time. Interestingly, the Berlin Painter inscribed the names of his characters on the London krater. And yet, we do not even know his real name since none of the works attributed to him indicates it. The nickname “The Berlin Painter” was given to him by the prolific scholar, Sir John Beazley, who attributed the makers of some 30 thousand items of Athenian ceramics. The nickname is based on the amphora located in Antikensammlung in Berlin, excavated in the Etruscan city, Vulci. This amphora served as the “mother-work” of the Berlin Painter--the vase to which other found works and fragments were compared in terms of stylistic details, resulting in matching them to the hands of one maker. Some of the stylistic details of the Berlin Painter, which revolutionized the red-figure technique, include:

What we know about him as a person, we can only guess from the themes he chose for his imagery; he was fond of animals and nature, probably liked poetry and city festivals and, of course, gave homage to the gods. He avoided the otherwise common themes of bloody combats and gory scenes, or those of debauchery and drunkenness. Even his depictions of satyrs seemed to emphasize their human nature over the animalistic. The Berlin Painter just seems like a mellow, content man. Other works by The Berlin Painter: In 1911, Beazley assigned 38 vases to the Berlin Painter (“master of the Berlin amphora”) and outlined the characteristics of the Berlin Painter’s renderings. His drawing style was described in 1922 and by 1925 there were already 148 vases attributed to the artist. As of today, over 400 works of pottery and fragments are attributed to the Berlin Painter. Because of their masterful artistry, they are highly appreciated and sought by the world’s museums. In the Gregorian Etruscan Museum in the Vatican Museums, there is the beautiful hydria with Apollo sitting on the winged tripod, playing the lyre, as two dolphins below make their way back into waters. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has 13 vessels. Among them is another hydria, featuring Achilles slaying Penthesilea, the queen of the Amazons. This museum has arguably one of the most exquisite of all vases by the Berlin Painter, the type C amphora with the beautiful walking-singing citharode—youth playing the kithara—on one side and the contest judge on the other side. The Louvre has the largest collection of his vases, for a total of 36. The only cup known to be painted by this artist (although debates over the attribution continue) is in the Agora Museum in Athens. It is called the Gorgos Cup, after the potter Gorgos, who provided the vessel to be decorated. The name "Gorgos" as the maker of the vessel is inscribed on the cup. While some painters were also potters of the vases they worked with (and it is possible the Berlin Painter was among them in some instances), the transition from potter to painter was not at all automatic. There are also the Panathenaic amphorae painted by the Berlin Painter. Those were the vases that were filled with olive oil and given as prizes to winners of the Panathenaic Games. They were always traditionally done in the black-figure technique. Only highly esteemed painters were commissioned to provide those. Out of 21 vases painted by the Berlin Painter in the black-figure technique, possibly only two are not the Panathenaic amphorae (a fragmented amphora Type A in New York and a hydria in Frankfurt). While vases, in general, were popular in antiquity and were given as burial offerings to go with the departed close ones, only the wealthy could afford to have a vase decorated by, say, the Berlin Painter or other artists of high esteem. The amphorae given to victors of the games were a sign of the prestige of the artist whom they were commissioned to.

Legacy: There were three immediate students of the Berlin Painter, who were all very important and painted a large number of vessels: The Providence Painter, Hermonax and The Achilles Painter. The last of them, along with his own student, the Phiale Painter, closed the workshop of the Berlin Painter in 425. Although the workshop closed, many features of the Berlin Painter’s innovative style remained with generations of vase painters.

The students of the Berlin Painter and other followers who came even later into the vase painting world (the Harrow Painter, the Tithonos Painter, the Painter of the Yale Lekythos, Alkimachos Painter, just to name a few) carried on the legacy of the master by either adopting his ornamentation style, features of the design (the “less is more” on the vase), or took up shapes which were not popular among the red-figure artists before the Berlin Painter. The Berlin Painter was not only the master of the already existing technique but developed it as well as expanded the repertoire of shapes which began to be painted in the red-figure technique. He was not just the master of his technique but a thinker and inventor.

Where? Room 9 of the National Gallery

When? 1565-1570 Commissioned by? The Pisano family, probably Francesco Pisani What do you see? This painting is full of activity. The main attention goes to the two groups of life-size people in the foreground. The painting shows how the family of Persian King Darius (in the center) appears in front of King Alexander the Great and his following (on the right) to ask for mercy. The man on the right, dressed in red and gold, is Alexander the Great. To his right, with the orange cape, is his good friend and advisor Hephaistion who is pointing to himself. Alexander is further surrounded by other high-ranked officers in his army, some of which a carrying a weapon called a halberd. The woman in blue in the center foreground is the mother of Darius, Sisygambis. She is pleading for mercy on behalf of her family. To her left, dressed in gold is the wife of Darius, Stateira, and to her left are their two daughters in beautiful identical dresses. To the right of Sisygambis is a small figure. Some say that this may be a son of Darius and Stateira, but most consider this to be a random dwarf. Alexander uses his right hand to silence Sisygambis and his left hand to point at Hephaistion as Sisygambis initially incorrectly spoke to Hephaistion instead of Alexander. The meeting between both groups takes place in an open hall within a big palace. Veronese paints the various figures in this painting in colorful and expensive contemporary Venetian outfits. The other figures in this painting are not important for the story but are basically onlookers just like us (though most of them do not seem to be interested in the main scene).

Backstory: The painting is based on the third book of the "History of Alexander the Great" by Quintus Curtius Rufus (see the full text of this book here) and the third book of the “Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings” by Valerius Maximum.

In 333 B.C., the Greek and the Persians were at war. Darius III was the King of Persia and Alexander the Great was a Greek king and army general. Alexander was aggressively expanding his territories around this time. The Greek just won the Battle of Issus (which is depicted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder). Darius fled the battle, but the Greeks captured his family. In this painting you can see the family of Darius asking for mercy to Alexander the Great. Typically, mercy was not granted and the family would be enslaved, raped, or killed. In this case, Alexander granted them mercy. Alexander actually married the oldest daughter in this painting, Stateira II, later on. The youngest daughter married later to Hephaistion.

Alexander the Great: This painting shows an important moment in Alexander the Great’s life. Hephaistion is of the same age as Alexander (around 22 years in this painting) and actually taller than him. Because of this, the mother of Darius makes a big mistake by actually addressing the advisor of Alexander instead of himself. You can see that her mouth is open and her fingers are spread as she realizes her mistake. Alexander, however, steps forward and by his hand gestures, you can see that he forgives the mistake and explains that Hephaistion is his advisor.

According to Valerius Maximus, Alexander says: “There is nothing amiss in your having taken him for me, for he too is Alexander.” This gesture shows that, besides Alexander being a great general, he is also a diplomatic leader. At the time that this painting was created, the Venetians were at war with the Turks. So, the Pisano family commissioned this painting to teach the values of Alexander the Great to the visitors to their villa. Who is Veronese? Paolo Veronese (1528-1588) was born in Verona, Italy. He is especially known for his very large historical paintings. He learned a lot from Titian and Tintoretto, who were contemporaries and were a bit older than him. He used a lot of bright colors in his paintings, something that is typical for the painters from the Venetian School. The reason for this was that the pigments arrived in Italy through the port of Venice and thus the most beautiful colors were widely available there for the best painters. In his work, Veronese was interested in using historical stories to provide some useful life lessons to the people in Venice. Veronese also liked to include some funny details in his paintings which were not part of the narrative. Often these were a variety of animals. See, for example, also all the animals in his masterpiece The Wedding at Cana, which is in the Louvre. While this was fine to do in paintings with a nonreligious context, he actually would get in trouble when he also did that in paintings with a religious subject.

Fun fact: Veronese included some funny details in this painting. Noticeable is the chained monkey to the left of the family of Darius. Look also at the young boy holding Alexander’s robe who is looking at us. On the bottom right, you can see a boy bending over a shield as he is trying to see what is going on.

On the top right is a gigantic horse, which is the horse of Alexander and is much bigger than the other horses on the left of the painting. You can even look through some of the horses on the left as the paint has become more transparent over time. On the bottom right, you can see a big dog being held back by one of the soldiers, while on the left, you see some small and friendly dogs being held.

Where? Room 18 of the National Gallery

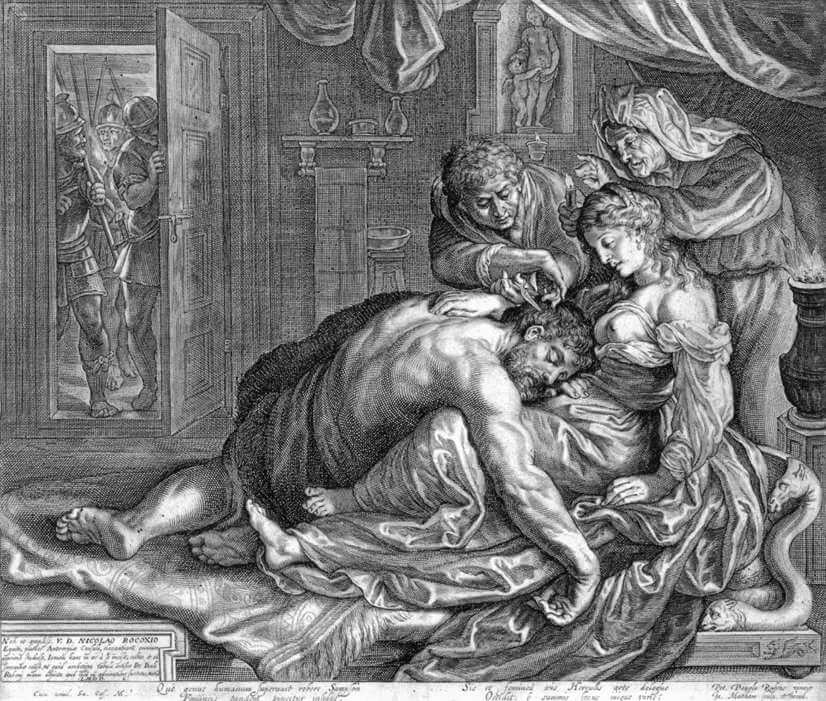

When? 1609-1610 Commissioned by? Nicolaas II Rockox, a kind of mayor of Antwerp What do you see? Samson and Delilah are lying in a bed. The very muscular Samson is almost naked and sleeping on the lap of Delilah. He is only wearing an animal skin (possibly of a lion that he killed with his bare hands) around his middle. Delilah is wearing a white dress with a red satin cloak and has her breasts exposed. Her face shows a gentle expression and her left hand is placed on the shoulder of Samson. The man behind Samson cuts his hair which was the source of Samson’s extraordinary strength. On the left side, an old woman is holding up a candle to provide enough light to cut Samson’s hair. On the bottom right, below Samson and Delilah, is an expensive woven carpet. On the top right, the Philistine soldiers are waiting outside the door with their weapons to capture Samson after his hair is cut. In the background of the room are various decorations. Notably, on the top left is a statue of Venus and Cupid. A large purple curtain surrounds the statue. Backstory: This painting was acquired by the National Gallery in 1980 for about $6 million. At that time, it was the second-most expensive painting in the world. This painting hung originally above a very large fireplace in the house of Nicolaas II Rockox. The bottom of the painting was about three foot/meter above the floor. Rubens created the painting such that it is best appreciated when viewed from below, though it is difficult in the current museums to hang a painting that high above the floor. A preliminary study for this painting is in the Cincinnati Museum of Art.

The Biblical story of Samson and Delilah: The story of Samson is described in Judges 13-16. He was a judge of the Israelites and received an immense strength from God to fight his enemies. The only condition to not lose his strength was that he could not cut his hair. He used his strength multiple times against the Philistines, the enemy of the Israelites.

However, as described in Judges 16, one day he falls in love with the Philistine girl Delilah. The Philistines bribe Delilah to help them to capture Samson. Delilah asks Samson multiple times what the secret of his strength is such that the Philistines can get rid of it. After telling a couple of lies first, he finally tells her that the secret is that he cannot cut his hair and that he never did (interestingly, his hair is rather short in this painting). Delilah makes Samson fall asleep in her lap and a servant cuts his hair. When the Philistines come to capture him, God has left Samson and he has lost his strength. He gets captured by the Philistines and is put in prison. After that Samson got his strength back one more time from God and killed himself and more Philistines than he had done his entire life. Symbolism: The moral of this painting is that love can cause problems. Some people even suggest that this painting portrays a brothel and if that is the case, the message of Rubens is that you should not visit those. The crossed hands of the man cutting the hair of Samson symbolize betrayal. The statue of Venus and Cupid in the background shows that the mouth of Cupid is covered by a cloth such that he cannot speak. This is an uncommon way to depict Cupid and symbolizes the belief of Samson that love (represented by Cupid) can lead to bad outcomes. Who is Rubens? Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) is one of the most famous Baroque painters. Between 1600 and 1608, he spent a considerable amount of time in Italy and visited, among other cities, Venice, Florence, and Rome. He was able to see a lot of art masterpieces there and was particularly inspired by the works of Caravaggio, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. In 1608, he moved back to Antwerp where he started his extensive studio. Rubens developed a unique painting style with an emphasis on color, movement, sensuality, and light. He created a large number of paintings, including religious ones such as the current painting and Daniel in the Lions’ Den in the National Gallery of Art, and mythological paintings such as Prometheus Bound in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fun fact: There has been quite some debate over time about whether Rubens actually created this painting. While there is no doubt that Rubens created a painting of Samson and Delilah, the question is whether the version in the National Gallery is the one that Rubens painted or whether the real Rubens has been lost.

An important argument that this may not be a Rubens is related to a copy of the real Rubens painting in 1613 by Jacob Matham. There are several differences between the copperplate engraving of Matham and the painting of Rubens, such as the right foot of Rubens which is not entirely in the painting, the position of the old woman, the statue of Venus and Cupid in the background, and the carpet. The main argument that this painting is not by Rubens is that the copy by Matham is more in line with the other paintings of Rubens than the painting in the National Gallery. However, nowadays most people believe that Rubens did make the painting in the National Gallery.

Where? Room 57 of the National Gallery

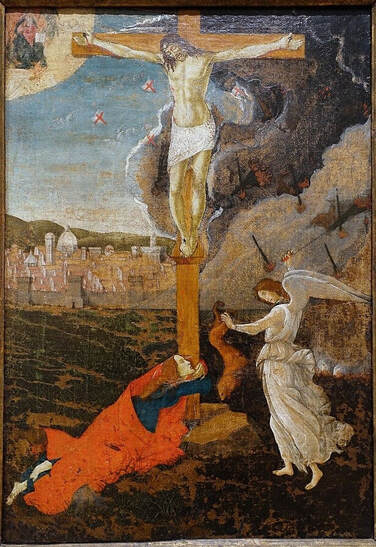

When? 1500 Commissioned by? Botticelli probably made this picture for himself What do you see? In the center of this painting, you can see a naked baby Jesus. His mother, the Virgin Mary, is depicted to his right and is much larger than the other figures. His father, Saint Joseph, is on his left. Behind Jesus are a horse and an ox. Together they are staying in a stable. On top of the stable are three angels. One is reading a book, and the other two are holding an olive branch. To the left of Joseph is an angel in pink, holding an olive branch with a scroll attached to it, while reaching out to Joseph to introduce the three wise men. On the right of Mary is another angel with three shepherds who want to pay their respects to Jesus. In the foreground are three pairs consisting of one angel and one man embracing each other. Each pair holds an olive branch in their hand with a scroll attached to it. They are surrounded by several little imps or devils who are killing themselves with their spears. On top of the painting is a choir of 12 angels holding hands. The angels are doing a mystic ring dance. They are also holding an olive branch in their hands with a scroll attached to it and a crown hanging at the bottom of the branch. The angels are under the golden dome of heaven. Above this dome is a Greek inscription based on some parts of the Revelations of John related to the apocalypse. Backstory: This painting is also called ‘The Mystical Nativity’, and it is the only painting that Botticelli signed. This painting combines the story of the birth of Jesus with his return to earth according to the apocalypse. The title of this painting contains the word mystic because the parts of the painting referring to the apocalypse are prophetic and express a mystery. The word mystic is occasionally used to refer to exceptional paintings with mysterious and symbolic content. Another example of such a painting is the Mystic Crucifixion by Botticelli which is in the Fogg Art Museum in Boston.

Inscription: The inscription on top of the painting contains a message in Greek. It is translated as: “I Sandro painted this picture at the end of the year 1500 in the troubles in Italy in the half time after the time according to the 11th chapter of St. John in the second woe of the Apocalypse in the loosing of the devil for three and a half years. Then he will be chained in the 12th chapter and we shall see him trodden down as in this picture.” This message of Botticelli is based on the 11th and 12th chapter of the Revelations of John.

Botticelli believed that the apocalypse as described in the Bible was going to happen in 1504. Specifically, he believed that he was living in the Tribulation, a short period of time in which the world would suffer from hardship and disasters. He believed that the Millennium, a period of a thousand years during which Jesus would return to earth, would start in three and a half years. This belief of Botticelli was particularly based on the various wars going on at that time and the hanging, two years earlier, of the Florentine preacher Savonarola of whom Botticelli was a follower. Symbolism:

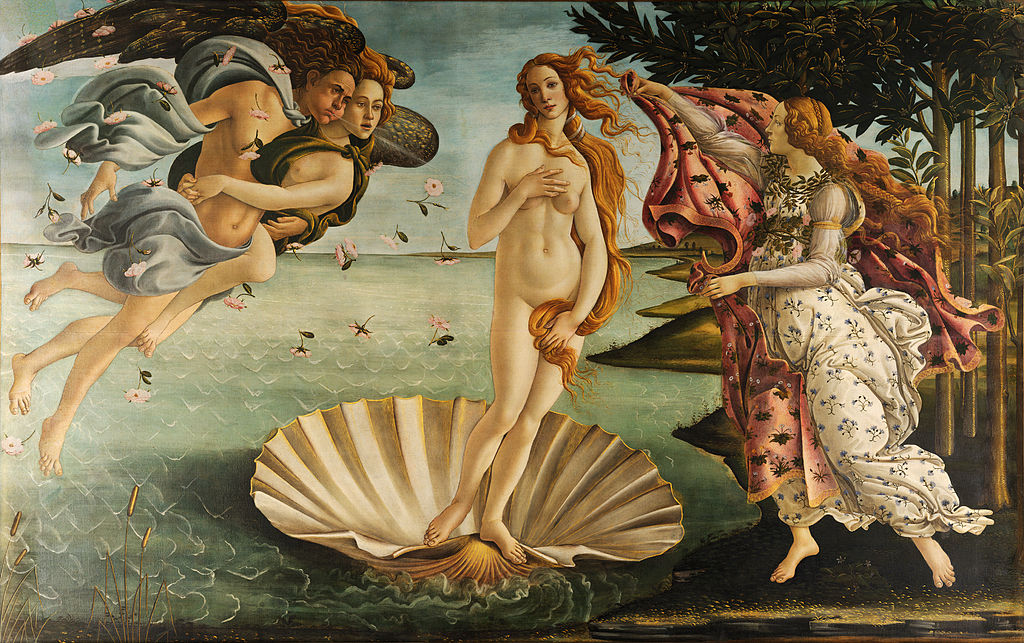

Who is Botticelli? Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) was born as Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi in Florence. Most of his paintings have a religious theme, but he also painted portraits and mythological scenes. The latter theme resulted in his most famous works, such as The Birth of Venus and La Primavera, both in the Uffizi Museum. His painting of Venus and Mars, which is also in the National Gallery, is also a masterpiece. In the 1490s, Botticelli got heavily influenced by the extremist preacher Savonarola, and he even stopped painting for a while to become a full member of Savonarola’s sect. However, he picked up painting again after a while, though his productivity was lower than before (though this is not entirely certain as almost all paintings of Botticelli are undated).

Fun fact: The Nativity scene in this painting is the story of the birth of Jesus as described in the gospels of Matthew and Luke. Mary was still a virgin, and God promised her that she would give birth to the Christ. The accounts of Matthew and Luke, however, differ quite a bit and both have their unique components.

According to Matthew, Jesus was visited by three wise men who followed a star to worship him. Luke describes that an angel announces the birth of Jesus to the shepherds and that they subsequently visit Jesus. Also, according to Luke, but not according to Matthew, the birth of Jesus happened in Bethlehem and Jesus was born in a stable. Botticelli combined elements from both gospels for this painting. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster of canvas.

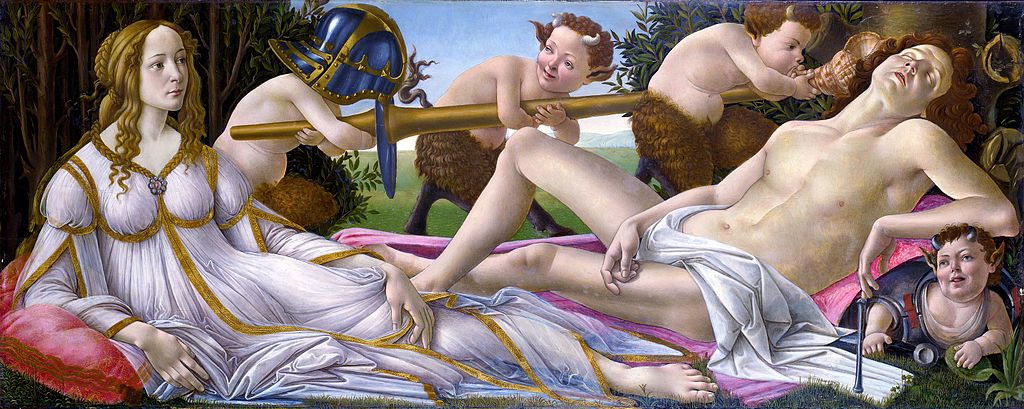

Where? Room 58 of the National Gallery

When? 1482-1485 What do you see? On the left, you see the goddess Venus who is carefully watching the god Mars on the right, who is asleep. Venus and Mars are having an adulterous affair. Uncharacteristically, Mars is unarmed, and he lies on a red cloak. You can also see four fauns (mythological figures who are half human and half goat, have small horns and tails, and they are followers of Bacchus). The fauns are blowing a Triton’s shell (a hunting horn in ancient times) like a trumpet in the ear of Mars to show that after making love even this very loud sound will not wake him up. They are also jokingly playing with the weapon of Mars (a lance), his body armor (to be precise, a cuirass; see the faun on the bottom right) and his helmet (the faun on the left). Venus is wearing a beautiful dress. On the top right you can see a swarm of wasps. Also, if you look carefully, you can see the city of Florence in the distance. Backstory: This painting is both inspired by Greek mythology and a description of the Greek writer Lucian of Samosata (125-180) of a lost painting on Alexander the Great and his wife, Roxana. According to the mythological stories, Venus is still married to the blacksmith Vulcan (the god of fire) when she is having an affair with Mars. Whenever Venus was having an affair, Vulcan would get so angry that he treated the metal with such force that it created a volcanic eruption. Based on the dimensions of the painting (27 x 69 inches – 69 x 174cm), this painting was likely meant to be a decoration for the backboard of a bed or a storage box. The National Gallery acquired the painting around 1874 for £1,050. Symbolism: The overall message of this painting is that love trumps war. Venus (the goddess of love) is awake, while her lover Mars (the god of war) is asleep. On the top right, you can see a swarm of wasps, which represent the stings of love. They may also refer to the Vespucci family (vespa is Italian for wasp). Simonetta Vespucci was a beautiful woman who most likely served as the model for this painting, and she was the inspiration for many of Botticelli’s paintings. The myrtle trees behind Venus are one of the main symbols of Venus as myrtles are known as a potent aphrodisiac. Who is Botticelli? Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) was a painter who belonged to the Florentine school of painters. Botticelli was initially trained by his brother to become a goldsmith, but at the age of 14, he became an apprentice to the successful painter Filippo Lippi (1406-1469), known from the painting Madonna and Child with Two Angels. Greek mythological stories often inspired Botticelli’s work, and he used Venus more often as a topic for his work. For example, Venus was also the center of attention in his famous paintings The Birth of Venus and La Primavera, both in the Uffizi Museum. Botticelli was in love with Simonetta Vespucci (a cousin-in-law of the explorer Amerigo Vespucci), who was already married to someone else. Simonetta was known as the greatest beauty of her time and died in 1476. As a result, Botticelli never married. Throughout his life, he has been inspired by Simonetta, who has served, according to popular belief, as the inspiration for many of his paintings (including the current one). According to his wish, Botticelli was buried at the feet of Simonetta Vespucci.

Who are Venus and Mars? Venus is the Roman goddess of love, beauty, sex, fertility, prosperity, and desire. Venus is also known in the Greek mythology as Aphrodite. In Latin the noun Venus means ‘sexual desire’. Julius Caesar claimed to be an ancestor of Venus.

Mars, the god of war, is one of the lovers of Venus. Mars is also an agricultural guardian. The Greek counterpart of Mars is Ares. The third month of the year, March, is named after him. In many mythological stories, Cupid is portrayed as the son of Venus and Mars.

|

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us