|

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

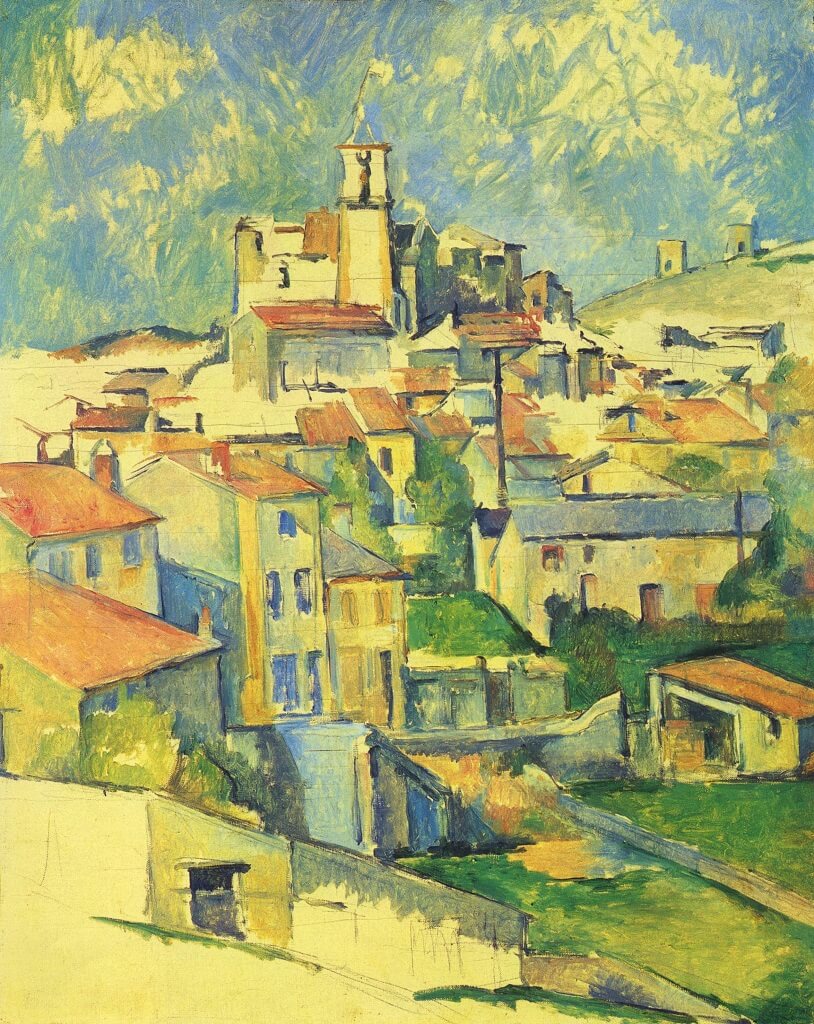

Where? Barnes Foundation, Room 2, West Wall.

When? c. 1885 Medium and size? Oil on canvas, 65.0 x 100.3 cm. What do you see? A horizontal view of the city of Gardanne in Southern France. The panoramic view is controlled by the use of blue/gray tones to collect and join each building block of the painting. There are squares and rectangles that build the scene, creating the illusion of distance and leading the eye upward to the highest point where the important bell tower has been positioned in the center of the work. The trees and greenery form their own shapes that give more cohesiveness to the buildings. The outline strokes and the shadows delineate the red roofs and gently lead the eye up the hill. On the right-hand side, just above the top of the hill, are two towers that may be from factories beyond. There is an architectural feel to the painting, but the warmth of the colors dispels any coldness. The scene appears to lean slightly toward the left, which may add further interest to the whole.

Background: Cézanne had been consistently rejected by the art critics, his boorish manners kept him from joining the "society" of Zola in Paris, and his father treated him with condescension. His mother wanted him to marry Hortense, formalizing a relationship that was already deteriorating. Pushed and pulled from every side, Monet wrote of him: "It is a great misfortune that this man has not enjoyed better support in his life. He is a true artist, but he has been brought to the point where he doubts himself too much… The more he was excluded, the more he opted out of society" (from Cézanne, Hajo Duchting).

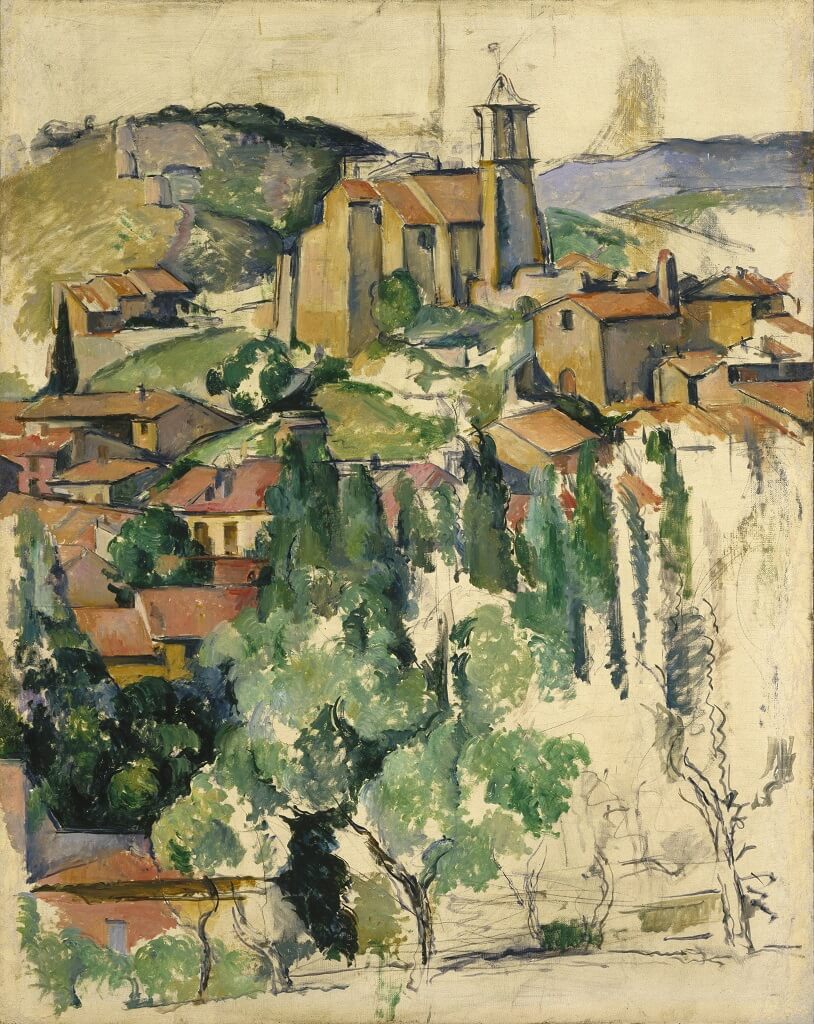

Cézanne could hardly be blamed for his retreat. He found solace in his painting and the nature that had become so dear to him: "Let us read Nature. Let us express our impressions and experiences in as aesthetic both personal and traditional. The strongest will be the one who touches the greatest depth and renders things entire—like the great Venetians." As he moved away from Impressionist techniques, he began to deal with the basic structure of the world. His constructive compositions established a new unity in his work. In 1885, he had an affair with a woman who has always remained a mystery. Not much is known about the relationship other than it was passionate, and it took Cézanne months to recover from it. He was distraught and wrote to Zola of his despair and inability to work well. There are unfinished works from 1885 that were the result of his lack of focus. The family was living at Jas de Bouffan as he tried to recover, and he was sent off to Gardanne each day to paint. Eventually, the walk became too much for him, and he, Hortense, and young Paul rented lodgings in Gardanne. He painted three views, including the one in the Barnes Foundation and the two below.

Each view provides a different perspective of the village, with the red roofs uniting each scene. The last view is one that he could not finish.

Cézanne also painted a view of Mount St. Victoire from Gardanne. The mountain would become one of his most famous motifs as he aged.

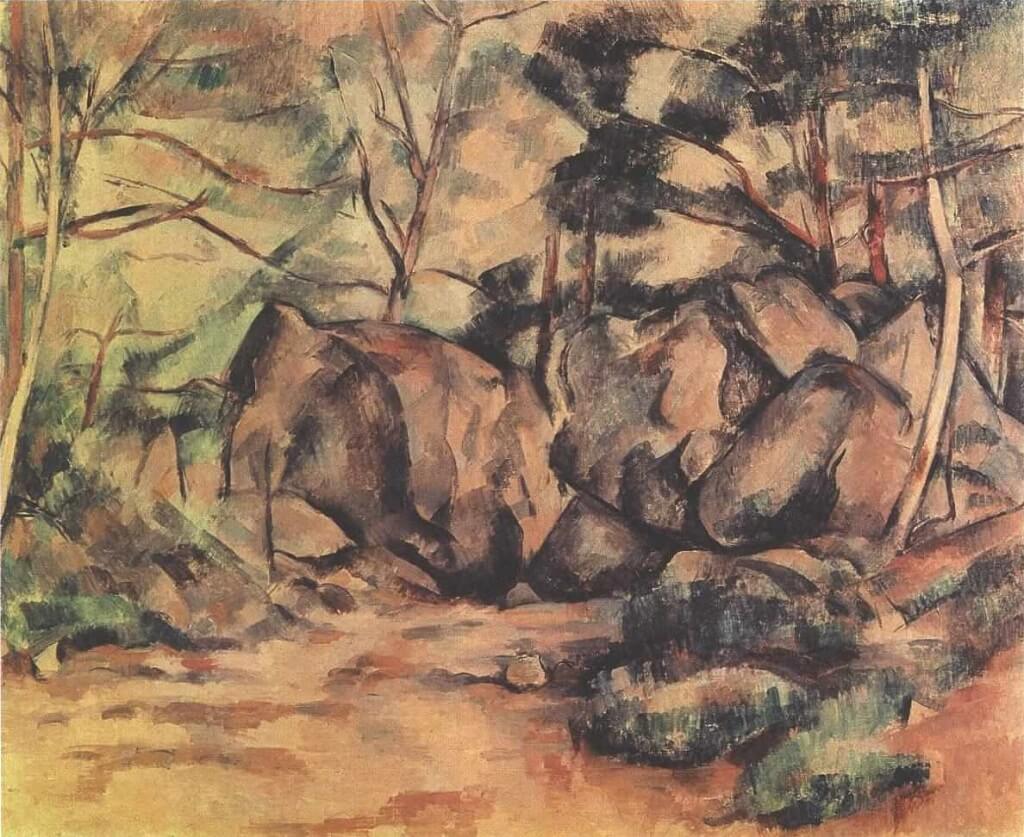

Constructive Brushstrokes: Cubism antecedents can be seen in the technique that Cézanne was developing as he forged a new era in art. His 'constructive strokes' became more pronounced after 1890. Each mark is planned in conjunction with the stroke 'before' and 'after.' There is precision in the construct with repetitive diagonal marks that move towards the vertical and then the opposite diagonal, mainly seen above. This is not abstract art nor a deconstruction of the subject. Cézanne still presented a solid, whole scene or object as he attempted to put feeling and sound into his viewers' heads by expressing his sensations.

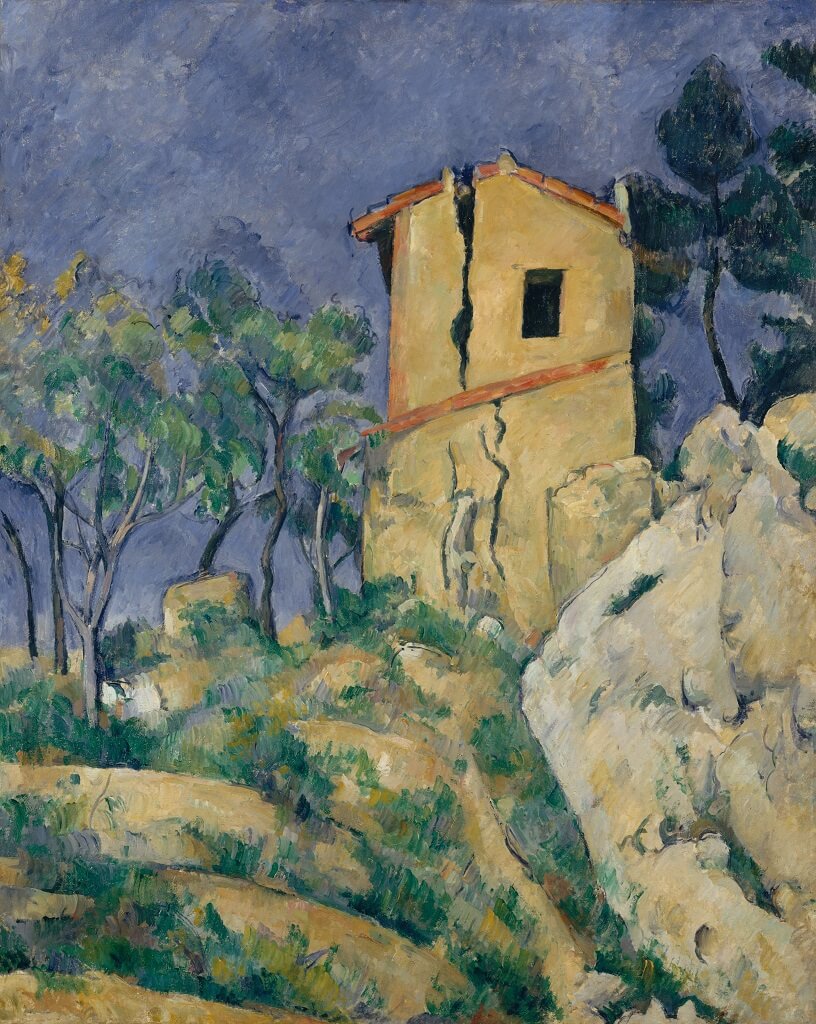

Post-Impressionism: Roger Fry coined the term "Post-Impressionists" to describe the artists that moved away from Impressionism. There was no intent to describe the work they did. Instead, it was a term to define who they were and to differentiate them in a period of change in art. Later definitions suggest that the Post-Impressionists "expanded on Impressionism while rejecting its limitations: they continued to use vivid colors, sometimes Impasto, and to paint from life but they were more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, distort forms for expressive effect and to use unnatural or modified color." The Post-Impressionists included Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Georges Seurat. More works from the Constructive Period: Cézanne experienced many momentous events from 1885 to 1895. His father had finally learned of the existence of Hortense and Paul, and after a period of wrath and rage, he increased Cézanne's allowance so that he no longer had to rely on selling paintings to survive. His affair was a major event, and his marriage to Hortense in 1886, at the insistence of his mother and sister, was another. The marriage made no difference to the mutual estrangement between the two partners, but they stayed together, not necessarily living together all the time. His father died later in 1886, and his inheritance relieved Cézanne of financial worry for the rest of his life. Zola's new novel was also released this year In it, Cézanne identified with the character of Claude Lantier, a "painter of genius, who is at odds with the whole world and himself and finally commits suicide." Cézanne felt used and abused by Zola, which was the end of their life-long friendship. Emile Zola died in 1902, and Cézanne regretted the break in their friendship until his death.

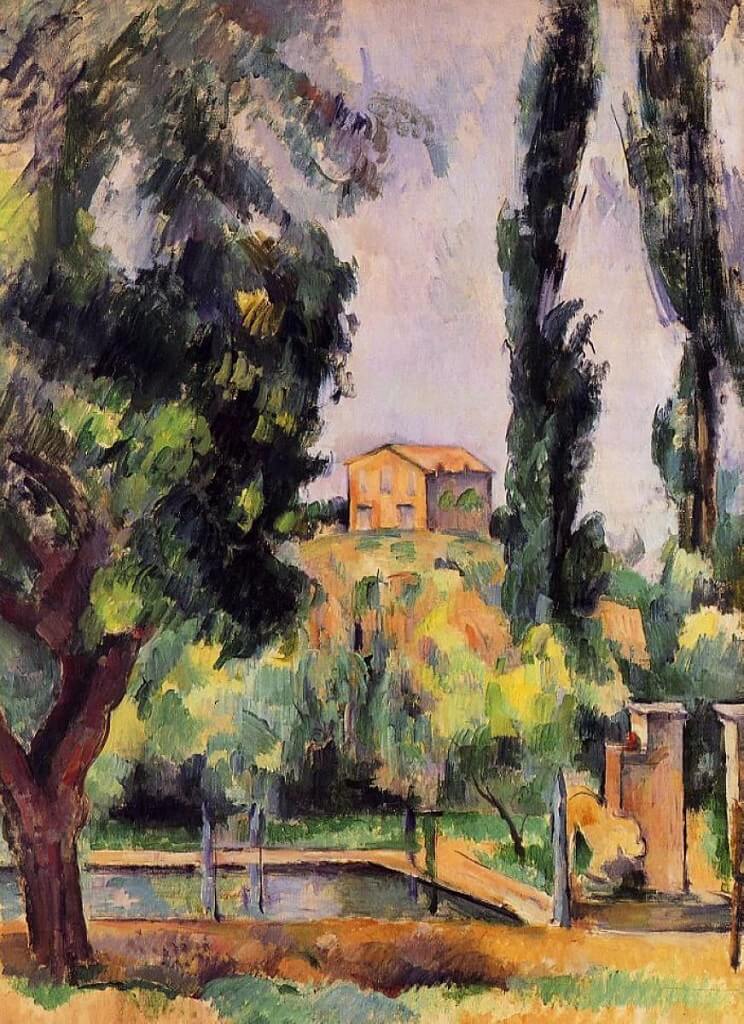

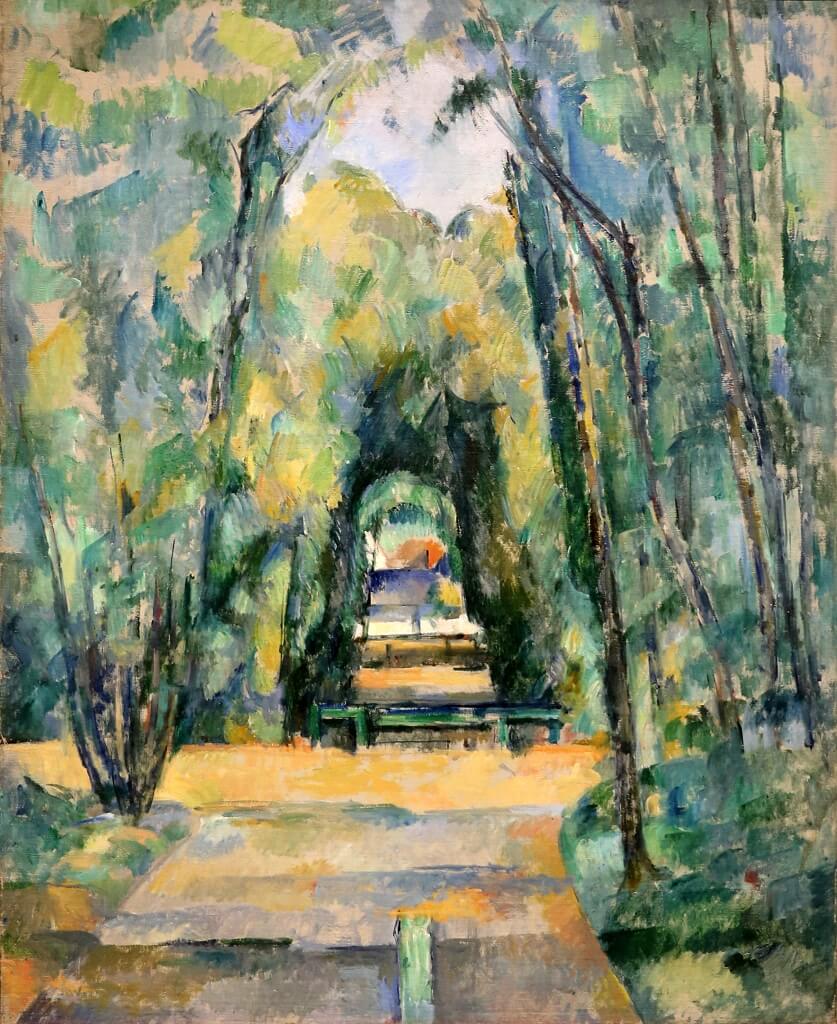

He spent much of 1887 in Aix, and in 1888, he met Van Gogh and Gauguin, but apparently, he was not impressed with their paintings. By 1890 he had the first signs of diabetes. Despite the chaos in his personal life, his work continued to evolve. The two paintings of The Alley at Chantilly in 1888 show the developing facets of color that would be so important in the final years of his work. These paintings were created with multiple tiny strokes from the colors embedded in the trees. The Great Pine sits in the central position, moaning and groaning as the wind whips through boughs and the trees behind.

In Maison Maria, the blue jolts the viewer down the road, past the houses, to the mountain in the background. Each of these paintings asks something of its viewers. Cézanne has his constructive brush strokes as his building blocks, his colors provide volume and solidity, and his composition guides the viewer.

Final Period, 1890–1906: In a follow-up post, Cézanne continues to be obsessed with his work. His own description: "The landscape becomes human, becomes a thinking living being within me. I become one with my picture… we merge in an iridescent chaos." His constructive brush strokes loosen, become lighter, layer upon layer, creating the depth and volume he always sought. He paints more in watercolors to attain the effects he sees as he transforms the landscape for himself and his viewers. By now, he is himself a recluse, but he has some successes and is becoming well known, possibly too late in his life for it to matter enormously.

Written by Carol Morse

References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us