|

Where? Room 8 of the Uffizi Museum

When? Between 1435 and 1460. The dating of this painting has been the subject of much debate, but most critics believe it is painted between 1435 and 1440. Commissioned by? Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni, a rich Florentine man who had a strong commercial interest in the battle of San Romano. What do you see? This painting shows a scene from the battle of San Romano on June 1, 1432. This battle was fought between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies. The central figure on the white horse is probably Bernardino della Ciarda. He was a former captain in the Florentine army but had recently defected to the opponents. He is fully armored and about to be thrown off his horse by a jousting lance. In the foreground, you can see several fallen horses and soldiers. The composition of the painting is not very realistic as the horses and soldiers in this painting look like dummies. The reason is that Uccello’s main interest in painting was not to perfectly depict a scene from history, but he was more interested in getting the linear perspective right. Look, for example at all the lances that are in this painting. Some are conveniently dropped on the ground in a geometrical pattern. The lances in vertical direction all point to the same vanishing point which Uccello wanted to incorporate to create depth in the painting. The vanishing point is just above the head of the white horse. In the background, you can see some soldiers and dogs hunting for rabbit and deer. Backstory: The battle of San Romano (a small place in Italy, near Lucca) was part of the war between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies from Genoa, Milan, and Siena. An important element of the war was about who would get access to the port of Pisa for trade. The battle of San Romano took place on June 1, 1432, and lasted less than a day. This battle was only a relatively minor battle, but the Florentines remembered it as a turning point in the war. This painting commemorates the Florentine victory in this battle, though Sienese sources disagree with this conclusion. The battle started when Florentine general Niccoló Tolentino was attacked after he was separated from most of his army when he was exploring the area. Tolentino and his small group of soldiers fought a brave fight and did not give up until another Florentine general, Micheletto Attendolo (who is at the center of the Louvre version of this battle), arrived at the battle scene with reinforcements. Attendolo and his army helped Florence to win this battle. The war dragged on for another year without a clear winner and in the end the war was settled through negotiations. Other versions of this painting? This painting is a part of a triptych (a work of art divided into three parts) made by Uccello. The three paintings represent different moments in the battle of San Romano. There are two alternative explanations about the order of the paintings. The simple explanation is that the three paintings represent the morning of the fight (the version in the National Gallery in London), the afternoon (the current version), and the evening (the Louvre version). A more popular alternative is that the National Gallery version represents the beginning of the battle with Niccoló da Tolentino. The Louvre version represents the arrival of Micheletto Attendolo and his army, and the current version shows the last episode where Bernardino della Ciarda from the opposing army was unhorsed. Note that the current painting of the battle in the Uffizi is the only of the three versions that is signed (see the words PAVLI VGIELI OPVS in the shield at the bottom left).

Who is Uccello? Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) was born as Paolo di Dono in Pratovecchio in Tuscany. In his teenage years, he was an apprentice of Lorenzo Ghiberti and later he got influenced by contemporaries such as Donatello, Brunelleschi, and Masaccio. He was named Uccello, which is Italian for ‘bird’, because he liked to paint birds. He developed strong scientific interests and was very interested in representing perspective in paintings, something that he and contemporary artists just introduced to painting.

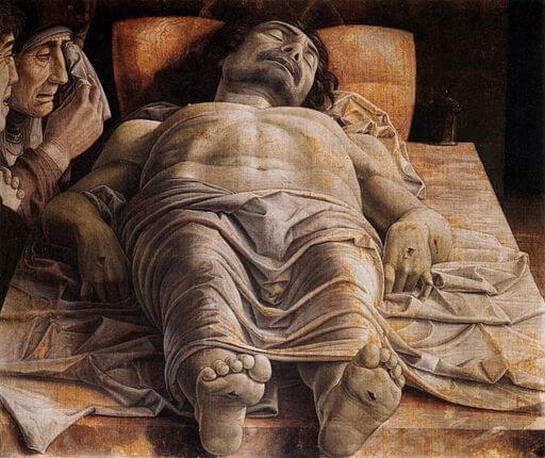

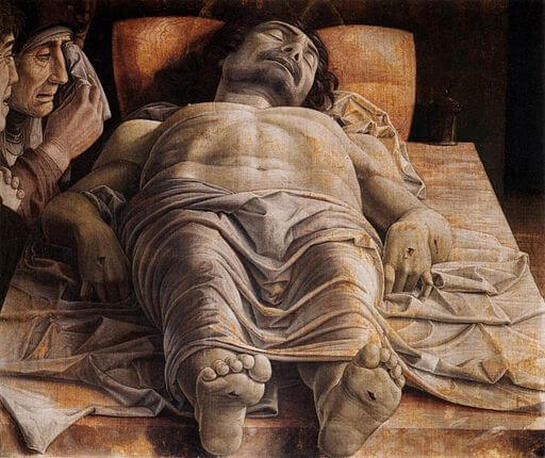

The appropriate use of linear perspective was often more important for Uccello than what the painting should represent. In his paintings, he combines elements of the older Gothic tradition (the decorative parts) and the newer Renaissance movement (which introduced depth and perspective). Linear Perspective? Linear perspective was developed around 1420 by Brunelleschi. It was a completely new approach to represent space in paintings. The simplest idea of perspective is that the size of objects becomes smaller the further away they are from the observer. Paintings with perspective have one or multiple vanishing points which help the painter to create perspective. Foreshortening is a specific form of perspective in which an illusionary trick is used to provide the idea of depth. A great example is when someone wants to paint a picture of a person laying with his feet towards you. To create the idea of depth, the painter will paint the feet of the person bigger than his head. The Lamentation of Christ by Mantegna is a great example of foreshortening. Note that the linear perspective in Uccello’s paintings is not perfect, but it did help to create depth in two-dimensional paintings. His work served as an inspiration for many artists in the next generations who perfected his ideas about linear perspective in paintings.

Fun fact: This painting of Uccello and its two companion pieces in the Louvre and National Gallery originally had an arched top, possibly a Gothic arch. However, these arches have been cut away around the time that Lorenzo the Medici seized the paintings from the commissioning Salimbeni family. The paintings were changed into rectangular formats and some additions were made to the top corners.

There is clear evidence that the top left and right corner did not originally exist, but these additions were made at the end of the 15th century. It is very unlikely that Uccello made these additions, but the unknown artist that made these did a good job as the additions are very hard to notice with the naked eye. An analysis of the different layers for these additions, however, clearly reveals that some different materials and paint compositions are used.

0 Comments

Where? Room 7 of the Uffizi Museum

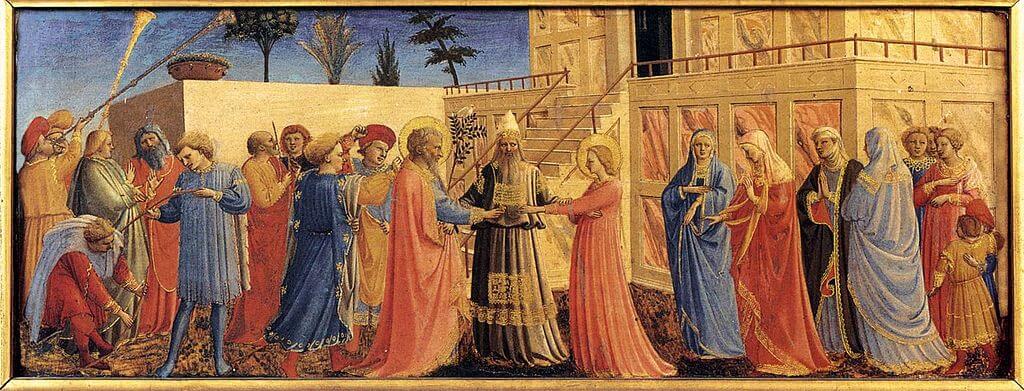

When? Between 1430 and 1435 Commissioned by? The nuns of the Santa Maria Nuova hospital in Florence. What do you see? Jesus and the Virgin Mary are on top of a series of small clouds, floating in the sky. This painting depicts paradise. Jesus is crowning the Virgin Mary as the Queen of Heaven. Mary has her arms crossed on her chest, slightly bends forward, and has a humble look on her face, while Jesus is decorating her golden crown with a jewel stone. Surrounding Jesus and Mary is a crowd of angels, blessed people, and saints. A choir of angels is playing music and dancing. You can see several angels scattered throughout the painting, recognizable by their wings, who are either playing music or are dancing. Three angels are dancing directly to the left of Mary, and you can see three others directly to the right of Jesus. On the top right and top left you can see some trumpets high up in the air and in the center foreground you can see two angels playing musical instruments. The angel in blue, turned with the back towards us, is playing a portable organ, and the angel to the left is playing a string instrument. Backstory: The painting probably formed an altarpiece together with two side panels, Wedding of the Virgin and Death of the Virgin, which are now both located in the Museum of San Marco in Florence. The painting contains both elements that are Gothic and elements that are typical for the Renaissance. For example, the golden background is gilded and is an element that was common in Gothic painting. The use of halos is also typical Gothic. The realistic way in which the people are depicted and the three-dimensionality are examples of the Renaissance style.

Symbolism: The gold crown signifies both power (by being an advocate of the king) and wealth (regarding God’s promises). Jesus and Mary are surrounded by bright rays of light, symbolizing their divinity.

What is the Coronation of the Virgin? Mary is crowned by her son Jesus as the Queen of Heaven. This occurs after Mary has been assumed into heaven. In ancient times it was common for the king’s mother to be crowned queen. This subject was quite popular in art since the 13th century. Why is Mary the Queen of Heaven? One of the many titles that Catholics have given to Mary is Queen of Heaven (Regina Caeli in Latin). Historically, in the Bible, the mother of the king had important powers in counseling the king and she was referred to as the Queen Mother. The reason that Mary is sometimes called the Queen of Heaven is that, according to the Catholic Church, Mary was assumed into heaven at the end of her earthly life. In Heaven, she is crowned as the queen (which is the coronation of the Virgin) as she is the mother of Jesus, who is the heavenly king of the universe. On October 11, 1954, Pope Pius XII decided that Catholics should celebrate the Queenship of Mary. Since 1969, the Queenship of Mary is a public holiday on August 22 in several countries, such as France and Spain. Another work of Fra Angelico on the Coronation of the Virgin? The current version originally belonged to the Church of Sant'Egidio in Florence and is shown in the Uffizi since 1825. However, Fra Angelico has painted another well-known version of the Coronation of the Virgin. This version is currently in the Louvre in Paris. In that painting, you can see that blue skies replace the more old-fashioned Gothic golden background.

Who is Fra Angelico? Fra Angelico was born around 1387 as Guido di Pietro and died in 1455. He was a Dominican friar and was widely respected because of his gentle personality. While he started in the monastery as an illustrator of manuscripts, he became known as a masterful painter of altarpieces.

Only after his death the name Fra Angelico was given to him. In his work he freely interpreted biblical stories, rather than accurately depicting the stories, to trigger spiritual responses of the people seeing those paintings and to stimulate prayer. Among his well-known works is The Adoration of the Magi, painted together with Filippo Lippi, in the National Gallery of Art.

Fun fact: Fra Angelico was known during his life as Il Beato Angelico or simply Il Beato (which means ‘the blessed’). He was a devout friar during his life and only painted religious works. He prayed before every painting, and once the painting was done he did not alter them anymore as he believed that God inspired his work. While he was already called ‘the blessed’ during his life, Pope John Paul II officially beatified him in 1982, praising his immaculate lifestyle and divine paintings.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas.

Where? First floor, room 708 of the Denon wing in the Louvre

When? Between 1435 and 1460. The dating of this painting has been the subject of much debate, but most critics believe it was painted between 1435 and 1440. Commissioned by? Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni, a rich Florentine man who had a strong commercial interest in the battle of San Romano. What do you see? This painting shows a scene from the battle of San Romano on June 1, 1432. This battle was fought between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies. The central figure is the Florentine general Micheletto Attendolo (also known as Michele Attendolo or Micheletto da Cotignola). There are several more figures and horses depicted in the foreground, each with their own role, creating a sense of movement in the painting. The soldiers on the right are waiting to participate in the battle. Micheletto on the black horse is giving the command to start the attack with his right hand, in which he is holding a sword. Unlike the other soldiers, Micheletto is wearing a big hat to signal that he is the general. Behind Micheletto, on the left, you can see two men holding a trumpet to communicate Micheletto’s commands to the Florentine army. The soldiers on the left are starting the attack with their lances in attacking position. In the background, you can see a forest of soldiers, horse legs, and lances conveying the chaos of a battle. Uccello used foreshortening to include perspective in this painting to make it look like a three-dimensional scene. Backstory: The battle of San Romano (a small place in Italy, near Lucca) was part of the war between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies from Genoa, Milan, and Siena. An important element of the war was about who would get access to the port of Pisa for trade. The battle of San Romano took place on June 1, 1432, and lasted less than a day. This battle was only a relatively minor battle, but the Florentines remembered it as a turning point in the war. This painting commemorates the Florentine victory in this battle, though Sienese sources disagree with this conclusion. The battle was started by Florentine general Niccoló Tolentino (who is at the center of the National Gallery version of this battle) who got attacked after he was separated from most of his army while exploring the area. Tolentino and his small group of soldiers fought a brave fight and did not give up until another Florentine general, Micheletto Attendolo, arrived at the battle scene with reinforcements. Attendolo and his army helped Florence to win this battle. The war dragged on for another year without a clear winner, and in the end the war was settled through negotiations. Other versions of this painting? This painting is a part of a triptych (a work of art divided into three parts) made by Uccello. The three paintings represent different moments in the battle of San Romano. There are two alternative explanations about the order of the paintings. The simple explanation is that the three paintings represent the morning of the fight (the version in the National Gallery in London), the afternoon (the Uffizi version), and the evening (the current version). However, the question is whether the current version represents the evening or whether as the paint in the background has deteriorated over time. A more popular alternative is that the National Gallery version represents the beginning of the battle with Niccoló da Tolentino. The current version represents the arrival of Micheletto Attendolo and his army, and the Uffizi version shows the last episode where Bernardino della Ciarda from the opposing army has been unhorsed.

Who is Uccello? Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) was born as Paolo di Dono in Pratovecchio in Tuscany. In his teenage years, he was an apprentice of Lorenzo Ghiberti and later he got influenced by contemporaries such as Donatello, Brunelleschi, and Masaccio. He was named Uccello, which is Italian for ‘bird’, because he liked to paint birds. He developed strong scientific interests and was very interested in representing perspective in paintings, something that he and contemporary artists just introduced to painting.

The appropriate use of linear perspective was often more important for Uccello than what the painting should represent. In his paintings, he combines elements of the older Gothic tradition (the decorative parts) and the newer Renaissance movement (which introduced depth and perspective). Linear Perspective? Linear perspective was developed around 1420 by Brunelleschi. It was a completely new approach to represent space in paintings. A simple explanation of linear perspective is that the size of objects becomes smaller the further away they are from the observer. Paintings with perspective have one or multiple vanishing points which help the painter to create perspective. Foreshortening is a specific form of perspective in which an illusionary trick is used to provide the idea of depth. A great example is when someone wants to paint a picture of a person laying with his feet towards you. To create the idea of depth, the painter will paint the feet of the person bigger than his head. The Lamentation of Christ by Mantegna is a great example of a painting with foreshortening. Note that the linear perspective in Uccello’s paintings is not perfect, but it did help to create depth in two-dimensional paintings. His work served as an inspiration for many artists in the next generations who perfected his ideas about linear perspective in paintings.

Fun fact: This painting has deteriorated over time. For example, the background is much darker than initially painted by Uccello. Another area of strong deterioration are the armors in this painting. Uccello used gold and silver leaf for various parts of the painting. The gold leaf, which you can see on the decorations of the horses’ bridles, has remained in good condition over time. However, the silver leaf, mainly found on the armors of the soldiers, has oxydized over time and now looks more like dull grey or almost black.

Uccello was an apprentice of the goldsmith Lorenzo Ghiberti in his teenage years and was thus very familiar with the application of silver and gold leaf. Imagine this painting if the silver was still blinking in its old glory...

Where? Room 54 of the National Gallery

When? Between 1435 and 1460. The dating of this painting has been the subject of much debate, but most critics believe it is painted between 1435 and 1440. Commissioned by? Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni, a rich Florentine man who had a strong commercial interest in the battle of San Romano. What do you see? This painting shows a scene from the battle of San Romano on June 1, 1432. This battle was fought between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies. The person in the middle with the big red and gold hat (instead of a helmet) is Niccolò da Tolentino, a Florentine general. His white horse is standing on its back feet, and Niccoló is attacking the soldier from the opposing army on the grey horse on the right. Niccoló holds a short stick in his right hand, which identifies him as a general. To the left of Niccoló, you can see a boy with blond hair who is holding Niccoló’s banner, which is decorated with ‘knots of Solomon” symbols. The battlefield is bounded by a thick layer of vegetation with growing oranges, pomegranates, and flowers. Behind the vegetation is the hilly Tuscan landscape with several soldiers spread around. The main feature of this painting may not be the battle, but the linear perspective that Uccello included in this painting through the arrangement of the lances, flags, and knights in the foreground. Look specifically at all the broken lances in the foreground which are arranged in such a way that the vertical lances all point in the direction of a single vanishing point at the top of the head of the white horse. Uccello was one of the first artists to introduce linear perspective to painting. This means that the lances, flags, people, etc. are portrayed in proper perspective. For example, the warrior on the white horse in the center is supposed to be equally tall as the dead warrior laying on the ground to the left of him (though it may not appear to be the case according to most viewers). Backstory: The battle of San Romano (a small place in Italy, near Lucca) was part of the war between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies from Genoa, Milan, and Siena. An important element of the war was about who would get access to the port of Pisa for trade. The battle of San Romano took place on June 1, 1432, and lasted less than a day. This battle was only a relatively minor battle, but the Florentines remembered it as a turning point in the war. This painting commemorates the Florentine victory in this battle, though Sienese sources disagree with this conclusion. The battle started by Florentine general Niccoló Tolentino being attacked after he was separated from most of his army when he was exploring the area. Tolentino and his small group of soldiers fought a brave fight and did not give up until another Florentine general, Micheletto Attendolo (who is at the center of the Louvre version of this battle), arrived at the battle scene with reinforcements. Attendolo and his army helped Florence to win this battle. The war dragged on for another year without a clear winner, and in the end, the war was settled through negotiations. Other versions of this painting? This painting is a part of a triptych (a work of art divided into three parts) made by Uccello. The three paintings represent different moments in the battle of San Romano. There are two alternative explanations about the order of the paintings. The simple explanation is that the three paintings represent the morning of the fight (the current version), the afternoon (the Uffizi version), and the evening (the Louvre version). A more popular alternative is that the current version represents the beginning of the battle with Niccoló da Tolentino. The Louvre version represents the arrival of Micheletto Attendolo and his army. The Uffizi version shows the last episode where Bernardino della Ciarda from the opposing army has been unhorsed. In both explanations, the current version of the painting will represent the painting on the left of the original triptych.

Who is Uccello? Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) was born as Paolo di Dono in Pratovecchio in Tuscany. In his teenage years, he was an apprentice of Lorenzo Ghiberti and later he got influenced by contemporaries such as Donatello, Brunelleschi, and Masaccio. He was named Uccello, which is Italian for ‘bird’, because he liked to paint birds. He developed strong scientific interests and was very interested in representing perspective in paintings, something that he and contemporary artists just introduced to painting. The appropriate use of linear perspective was often more important for Uccello than what the painting should represent.

In his paintings, he combines elements from the older Gothic tradition (the decorative parts) and the newer Renaissance movement (which introduced depth and perspective). The current painting is a good example of the combination of styles. The use of perspective represents the Renaissance component, while the Gothic component is visible in the attention Uccello paid to the details of the armors and all the patterns in this painting. Linear Perspective? Linear perspective was developed around 1420 by Brunelleschi. It was a completely new approach to represent space in paintings. The simplest idea of perspective is that the size of objects becomes smaller, the further away they are from the observer. Paintings with perspective have one or multiple vanishing points which help the painter to create perspective. Foreshortening is a specific form of perspective in which an illusionary trick is used to provide the idea of depth. A great example is when someone wants to paint a picture of a person laying with his feet towards you. To create the idea of depth, the painter will paint the feet of the person bigger than his head. The Lamentation of Christ by Mantegna is a great example of foreshortening. Note that the linear perspective in Uccello’s paintings is definitely not perfect, but it did help to create depth in two-dimensional paintings. His work served as an inspiration for many artists in the next generations who perfected his ideas about linear perspective in paintings.

Fun fact: You can see ten soldiers scattered across the rolling hills in the background. Seven of them are dressed in clown-like, colorful pants and seem to perform various training tasks. Three of them are archers and hold crossbows in their hands. You can see two of them loading the crossbow with their feet as that was a physically demanding job. Two other soldiers on horses are standing across the road. Some people say that these soldiers are sent from the battlefield by Niccoló da Tolentino to ask for backup, though they do not seem to be in a big hurry.

|

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us