|

Where? Room 8 of the Uffizi Museum

When? Between 1435 and 1460. The dating of this painting has been the subject of much debate, but most critics believe it is painted between 1435 and 1440. Commissioned by? Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni, a rich Florentine man who had a strong commercial interest in the battle of San Romano. What do you see? This painting shows a scene from the battle of San Romano on June 1, 1432. This battle was fought between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies. The central figure on the white horse is probably Bernardino della Ciarda. He was a former captain in the Florentine army but had recently defected to the opponents. He is fully armored and about to be thrown off his horse by a jousting lance. In the foreground, you can see several fallen horses and soldiers. The composition of the painting is not very realistic as the horses and soldiers in this painting look like dummies. The reason is that Uccello’s main interest in painting was not to perfectly depict a scene from history, but he was more interested in getting the linear perspective right. Look, for example at all the lances that are in this painting. Some are conveniently dropped on the ground in a geometrical pattern. The lances in vertical direction all point to the same vanishing point which Uccello wanted to incorporate to create depth in the painting. The vanishing point is just above the head of the white horse. In the background, you can see some soldiers and dogs hunting for rabbit and deer. Backstory: The battle of San Romano (a small place in Italy, near Lucca) was part of the war between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies from Genoa, Milan, and Siena. An important element of the war was about who would get access to the port of Pisa for trade. The battle of San Romano took place on June 1, 1432, and lasted less than a day. This battle was only a relatively minor battle, but the Florentines remembered it as a turning point in the war. This painting commemorates the Florentine victory in this battle, though Sienese sources disagree with this conclusion. The battle started when Florentine general Niccoló Tolentino was attacked after he was separated from most of his army when he was exploring the area. Tolentino and his small group of soldiers fought a brave fight and did not give up until another Florentine general, Micheletto Attendolo (who is at the center of the Louvre version of this battle), arrived at the battle scene with reinforcements. Attendolo and his army helped Florence to win this battle. The war dragged on for another year without a clear winner and in the end the war was settled through negotiations. Other versions of this painting? This painting is a part of a triptych (a work of art divided into three parts) made by Uccello. The three paintings represent different moments in the battle of San Romano. There are two alternative explanations about the order of the paintings. The simple explanation is that the three paintings represent the morning of the fight (the version in the National Gallery in London), the afternoon (the current version), and the evening (the Louvre version). A more popular alternative is that the National Gallery version represents the beginning of the battle with Niccoló da Tolentino. The Louvre version represents the arrival of Micheletto Attendolo and his army, and the current version shows the last episode where Bernardino della Ciarda from the opposing army was unhorsed. Note that the current painting of the battle in the Uffizi is the only of the three versions that is signed (see the words PAVLI VGIELI OPVS in the shield at the bottom left).

Who is Uccello? Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) was born as Paolo di Dono in Pratovecchio in Tuscany. In his teenage years, he was an apprentice of Lorenzo Ghiberti and later he got influenced by contemporaries such as Donatello, Brunelleschi, and Masaccio. He was named Uccello, which is Italian for ‘bird’, because he liked to paint birds. He developed strong scientific interests and was very interested in representing perspective in paintings, something that he and contemporary artists just introduced to painting.

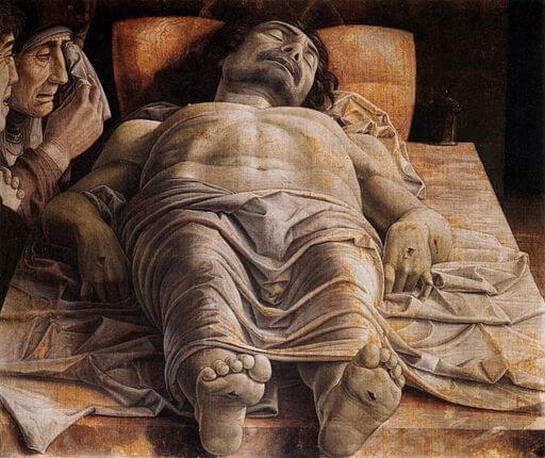

The appropriate use of linear perspective was often more important for Uccello than what the painting should represent. In his paintings, he combines elements of the older Gothic tradition (the decorative parts) and the newer Renaissance movement (which introduced depth and perspective). Linear Perspective? Linear perspective was developed around 1420 by Brunelleschi. It was a completely new approach to represent space in paintings. The simplest idea of perspective is that the size of objects becomes smaller the further away they are from the observer. Paintings with perspective have one or multiple vanishing points which help the painter to create perspective. Foreshortening is a specific form of perspective in which an illusionary trick is used to provide the idea of depth. A great example is when someone wants to paint a picture of a person laying with his feet towards you. To create the idea of depth, the painter will paint the feet of the person bigger than his head. The Lamentation of Christ by Mantegna is a great example of foreshortening. Note that the linear perspective in Uccello’s paintings is not perfect, but it did help to create depth in two-dimensional paintings. His work served as an inspiration for many artists in the next generations who perfected his ideas about linear perspective in paintings.

Fun fact: This painting of Uccello and its two companion pieces in the Louvre and National Gallery originally had an arched top, possibly a Gothic arch. However, these arches have been cut away around the time that Lorenzo the Medici seized the paintings from the commissioning Salimbeni family. The paintings were changed into rectangular formats and some additions were made to the top corners.

There is clear evidence that the top left and right corner did not originally exist, but these additions were made at the end of the 15th century. It is very unlikely that Uccello made these additions, but the unknown artist that made these did a good job as the additions are very hard to notice with the naked eye. An analysis of the different layers for these additions, however, clearly reveals that some different materials and paint compositions are used.

Written by Eelco Kappe

References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us