|

Where? Room 54 of the National Gallery

When? Between 1435 and 1460. The dating of this painting has been the subject of much debate, but most critics believe it is painted between 1435 and 1440. Commissioned by? Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni, a rich Florentine man who had a strong commercial interest in the battle of San Romano. What do you see? This painting shows a scene from the battle of San Romano on June 1, 1432. This battle was fought between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies. The person in the middle with the big red and gold hat (instead of a helmet) is Niccolò da Tolentino, a Florentine general. His white horse is standing on its back feet, and Niccoló is attacking the soldier from the opposing army on the grey horse on the right. Niccoló holds a short stick in his right hand, which identifies him as a general. To the left of Niccoló, you can see a boy with blond hair who is holding Niccoló’s banner, which is decorated with ‘knots of Solomon” symbols. The battlefield is bounded by a thick layer of vegetation with growing oranges, pomegranates, and flowers. Behind the vegetation is the hilly Tuscan landscape with several soldiers spread around. The main feature of this painting may not be the battle, but the linear perspective that Uccello included in this painting through the arrangement of the lances, flags, and knights in the foreground. Look specifically at all the broken lances in the foreground which are arranged in such a way that the vertical lances all point in the direction of a single vanishing point at the top of the head of the white horse. Uccello was one of the first artists to introduce linear perspective to painting. This means that the lances, flags, people, etc. are portrayed in proper perspective. For example, the warrior on the white horse in the center is supposed to be equally tall as the dead warrior laying on the ground to the left of him (though it may not appear to be the case according to most viewers). Backstory: The battle of San Romano (a small place in Italy, near Lucca) was part of the war between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies from Genoa, Milan, and Siena. An important element of the war was about who would get access to the port of Pisa for trade. The battle of San Romano took place on June 1, 1432, and lasted less than a day. This battle was only a relatively minor battle, but the Florentines remembered it as a turning point in the war. This painting commemorates the Florentine victory in this battle, though Sienese sources disagree with this conclusion. The battle started by Florentine general Niccoló Tolentino being attacked after he was separated from most of his army when he was exploring the area. Tolentino and his small group of soldiers fought a brave fight and did not give up until another Florentine general, Micheletto Attendolo (who is at the center of the Louvre version of this battle), arrived at the battle scene with reinforcements. Attendolo and his army helped Florence to win this battle. The war dragged on for another year without a clear winner, and in the end, the war was settled through negotiations. Other versions of this painting? This painting is a part of a triptych (a work of art divided into three parts) made by Uccello. The three paintings represent different moments in the battle of San Romano. There are two alternative explanations about the order of the paintings. The simple explanation is that the three paintings represent the morning of the fight (the current version), the afternoon (the Uffizi version), and the evening (the Louvre version). A more popular alternative is that the current version represents the beginning of the battle with Niccoló da Tolentino. The Louvre version represents the arrival of Micheletto Attendolo and his army. The Uffizi version shows the last episode where Bernardino della Ciarda from the opposing army has been unhorsed. In both explanations, the current version of the painting will represent the painting on the left of the original triptych.

Who is Uccello? Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) was born as Paolo di Dono in Pratovecchio in Tuscany. In his teenage years, he was an apprentice of Lorenzo Ghiberti and later he got influenced by contemporaries such as Donatello, Brunelleschi, and Masaccio. He was named Uccello, which is Italian for ‘bird’, because he liked to paint birds. He developed strong scientific interests and was very interested in representing perspective in paintings, something that he and contemporary artists just introduced to painting. The appropriate use of linear perspective was often more important for Uccello than what the painting should represent.

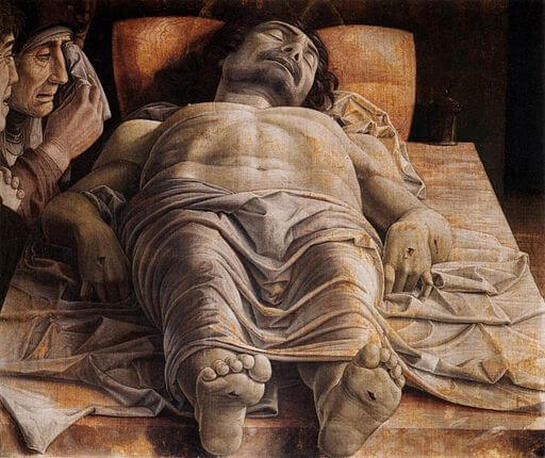

In his paintings, he combines elements from the older Gothic tradition (the decorative parts) and the newer Renaissance movement (which introduced depth and perspective). The current painting is a good example of the combination of styles. The use of perspective represents the Renaissance component, while the Gothic component is visible in the attention Uccello paid to the details of the armors and all the patterns in this painting. Linear Perspective? Linear perspective was developed around 1420 by Brunelleschi. It was a completely new approach to represent space in paintings. The simplest idea of perspective is that the size of objects becomes smaller, the further away they are from the observer. Paintings with perspective have one or multiple vanishing points which help the painter to create perspective. Foreshortening is a specific form of perspective in which an illusionary trick is used to provide the idea of depth. A great example is when someone wants to paint a picture of a person laying with his feet towards you. To create the idea of depth, the painter will paint the feet of the person bigger than his head. The Lamentation of Christ by Mantegna is a great example of foreshortening. Note that the linear perspective in Uccello’s paintings is definitely not perfect, but it did help to create depth in two-dimensional paintings. His work served as an inspiration for many artists in the next generations who perfected his ideas about linear perspective in paintings.

Fun fact: You can see ten soldiers scattered across the rolling hills in the background. Seven of them are dressed in clown-like, colorful pants and seem to perform various training tasks. Three of them are archers and hold crossbows in their hands. You can see two of them loading the crossbow with their feet as that was a physically demanding job. Two other soldiers on horses are standing across the road. Some people say that these soldiers are sent from the battlefield by Niccoló da Tolentino to ask for backup, though they do not seem to be in a big hurry.

Written by Eelco Kappe

References:

2 Comments

|

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us