|

Where? Room 96 of the Uffizi Museum

When? 1597 Commissioned by? Cardinal del Monte, who gave it as a gift to Ferdinando I de Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany What do you see? A depiction of the head of Medusa painted on a circular and curved wooden shield. Medusa is a figure described in Greek mythology. With her glance she could turn people who looked at her into stone. Instead of normal hair she has living, venomous snakes on her head. The snakes are watersnakes from the Tiber river as those were the best type of snakes Caravaggio could find nearby. I count at least eight snakes on her head. The blood streams out of her head as she has just been killed by the Greek demigod Perseus. This painting shows the moment that Medusa is looking at the reflective shield that Perseus is holding (which according to the myth actually happened just before she got beheaded). She realizes that her head is separated from her body, but that she is still conscious. You can see this realization by the horror in her eyes. As the painting is created on a shield, Caravaggio’s idea was that this painting actually represents the view of the shield as held by Perseus just after he killed Medusa. It is also interesting to have a closer look at Caravaggio’s use of light and shadow in this painting. Do you see how Caravaggio used these contrasts to show the head of Medusa as a three-dimensional object?

Who is Caravaggio? Michelangelo Merisa da Caravaggio (1571-1610) was trained by Simone Peterzano, who was in turn trained by Titian. He used a realistic painting style, paying attention to both the physical and emotional state of the subjects he painted. He combined this with a beautiful contrast between light and shadow in his paintings. He was a brilliant and unconventional artist.

During his life he received quite some commissions for religious paintings. However, Caravaggio always knew to how add some dark elements to the painting. He liked to use beggars, criminals, and prostitutes as models for his paintings, which would often give unexpected outcomes for familiar biblical scenes. Two beautiful examples of his religious paintings are the Death of the Virgin in the Louvre and The Entombment of Christ in the Vatican Museums.

Who is Medusa? In Greek mythology, Medusa was one of three sisters (Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa) who were often referred to as Gorgons. Both Stheno and Euryale were immortal, but Medusa was not. They were daughters of Phorcys (a sea god) and his sister Ceto (a sea goddess).

According to the Roman poet Ovid, Medusa was a beautiful young woman. However, after Poseidon (the god of the sea) made love to her in Athena’s temple, Athena (the goddess of wisdom and war) changed her beautiful locks into living, venomous snakes (in other mythological stories the three sisters were already born with snakes on their heads). Medusa had a horrific facial expression that could turn people (or according to some, only men) who looked at her into stone. The Greek hero Perseus, a demigod, used a shining shield that he got from the goddess Athena to avoid looking at her directly and succeeded to cut off her head. He used her head as a weapon afterwards as it retained its power to turn people who looked at it into stone. Perseus ultimately gave the head of Medusa to the goddess Athena, who placed the head on her shield (which is what is depicted in this painting). When the head of Medusa was cut off, two creatures arose from Medusa’s body: Pegasus, a winged horse, and Chryasor, a giant with a golden sword. Medusa in art? Medusa has been a popular subject in art. Famous artists have used her story as the inspiration for their artwork. Well known versions include:

Fun fact: Monica Favaro and colleagues published an academic study about the materials that were used in this painting and the evolution of these materials over time.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas (Amazon links).

2 Comments

Where? Room 90 of the Uffizi Museum

When? c. 1620 Commissioned by? Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo ll De’ Medici. The Grand Duke died in 1621, shortly after the painting was completed. It was only with the help of Artemisia’s friend, Galileo Galilei, that she managed to extract the payment for the agreed sum for the canvas. Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 146.5 x 108.0 cm. What do you see? The moment that Judith, with the help of her maidservant Abra, is beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes. Unlike many other artists, Artemisia Gentileschi chose to portray the scene at its zenith. It is the most powerful and horrific moment to imagine. Holofernes still struggles, his right hand fruitlessly trying to jab at Abra. His soon-to-be lifeless forearm comes to rest in the crook of her shoulder. His right knee is bent in a futile attempt to escape. Abra’s arms press downwards with great strain to hold Holofernes’ left arm down and still. The concentration and intense focus on what she is doing registers in her facial expression. Abra’s hair is covered with a white turban, and she wears a blue dress. The white sheet and the red coverlet lay rumpled over the commander. The sword's thrust in Judith’s hand produces blood spurts that reach Abra’s arm and Judith’s dress and body. Blood seeps over the bed and down the edges as life drains from him. His face is already losing the expression that gives it life, and it will soon be tucked into the food bag, wrapped in the bejeweled cloth that will be triumphantly removed once the two Jewish women return to their hometown Bethulia. Judith strains! The force she is expending is visible as she clutches the hair on Holofernes head and presses his head into the mattress with her left arm. Her right arm twists and rotates as the sword makes its cut. She uses the sword of Holofernes. The edge of the cross on the sword digs into the skin of his upper left arm, and we can see the pressure on it. Sleeves rolled up on both the women suggest they had some time to prepare, at least a bit, beforehand. He must have been quite drunk. The gown that Judith is wearing attests to the seduction that was her purpose. The low cut of the dress exposes her breasts and must have been enticing to Holofernes. Her hair is coiffed in the style of a noblewoman, uncovered, revealing its charms. She apparently was perfumed and prepared to seduce. Artemisia has painted one of her own bracelets on Judith’s arm in this second version of the scene. One cameo depicts Artemis, the ancient goddess of chastity and the hunt. It raises the question of whether Artemisia identified with this goddess? The textured walls of the tent provide a dark backdrop that not only frames the scene but also produces the contrast between light and dark that intensifies the actions of each individual. The light source comes from the left. The composition of the three figures focuses the viewer’s attention on the central part of the canvas.

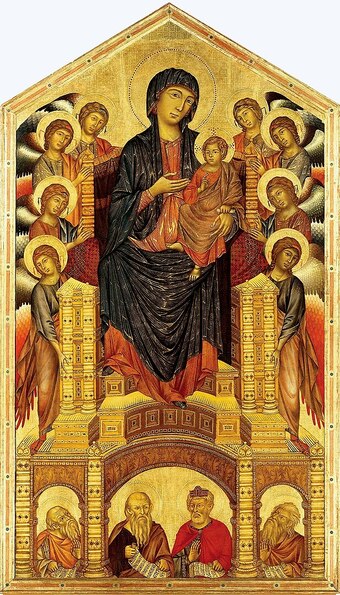

Where? Gallery 2 of the Uffizi Museum

When? Some time between 1280 and 1300, the precise date continues to be debated. Commissioned by? Probably by the Vallombrosans, a monastic order of the Catholic Church. What do you see? A majestic, Gothic altarpiece, in Byzantine tradition with the remarkable first signs of humanism that would dominate the Renaissance style. It measures 12’8” by 7’4” (385 by 223 cm) and is painted on large vertical wooden panels with golden background. The Virgin Mary is seated on an impressive marble throne, decorated with carvings, gems and mosaic designs, much like those seen in Tuscan churches of the time. She points to Jesus with her right hand, entreating viewers to seek salvation through Christ. The Madonna holds Jesus in the traditional Byzantine manner according to the icon, Hodegetria, meaning, “She who shows the way”. Jesus is dressed as a philosopher from ancient times and gestures a blessing while holding a rolled scroll in his left hand which is believed to be the scroll of law. The gilding on the clothing and drapery of the material they wear has been done using the Byzantine technique of “agemina”, indicating the application of 2 filaments (2 metals), of the precious golden decoration known as damascene.

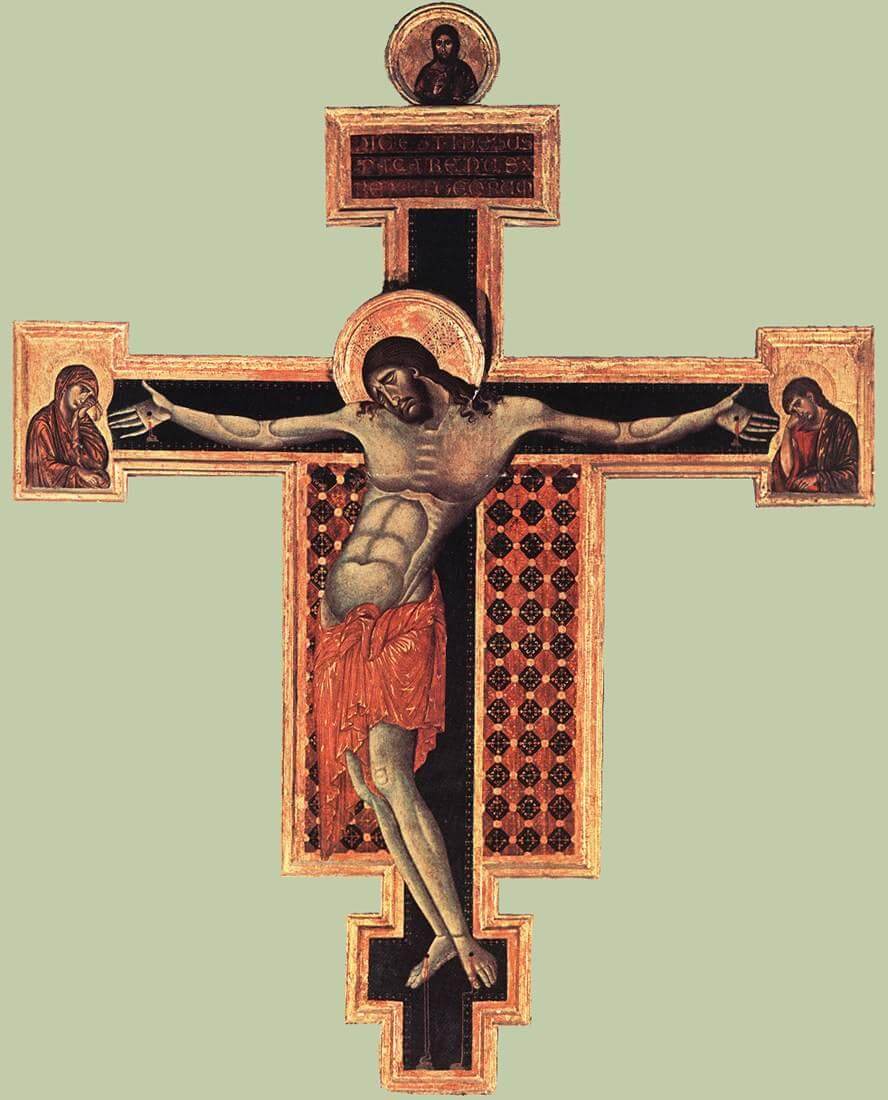

If it was commissioned by the Vallombrosan Order, they may well have requested the presence of the four prophets as they placed great emphasis on the Old Testament prophets in their literary and artistic traditions. Many other religious orders were being formed at the time and competition for the loyalty of Florence’s wealthy citizens and their financial support was important to any order. This spectacular and innovative Maestà that Cimabue created would certainly have brought new attention and prestige to the Vallombrosan at Santa Trinita. This large work would have been venerated with the intense devotion that the icons of the Byzantine style demanded, but it would also have been seen as a departure from the purely religious objective. What is a Meastà? Maestà is the Italian word for “majesty” and refers to the iconic formula of the enthroned Madonna as the Queen of Heaven with the Christ Child in her arms. She may or may not be surrounded by a court of angels and saints. It was a most common subject in the 13th and 14th centuries and was the object of intense devotion. Innovations: After some of the ancient Greek and Roman painters, Cimabue is one of the first to show linear perspective and to play with spatial features in his art. His figures take on volume and presence as they engage viewers not only in a pictorial story but also an important dialogue. His elegant angels have carefully designed hairstyles, each wearing decorative head bands. We can see two, wearing fashionable sandals, their bodies fill the volume of their diaphanous, draped clothing to the point that the knees are visible. They fully occupy the same space as the Madonna, helping to emphasize her importance but with more natural appearance. We can still see the elongated bodies and fingers, and the almond-shaped eyes of the Byzantine figures. The Madonna, by her size alone, continues to be the most important figure. Of note is the chiaroscuro effects of light and dark in the shading of the faces, suggestive of a light source, unseen in most Medieval work. Cimabue’s figures lose the rigidity of Greek and Byzantine art and for the first time since the Roman period, human emotions are seen in Florentine art. This can also be seen, for example, in his Crucifix (1268-1271) in the Basilica di Santa Croce in Florence. In this painting, Christ is showing the emotions on his face around the moment of his death.

Who was Cimabue? Cimabue was born c. 1240-45 in Florence and died in Pisa in 1302. He was a very innovative painter and used linear perspective, reintroduced volume and space, and, most significantly, human emotion in his paintings. While not much is known about his life, Cimabue first appeared in recorded history when it was noted that he witnessed the assumption of patronage by Pope Gregory X (Monastery of Saint Damiano) on June 18, 1272 in Rome. That he was in attendance suggests he was an experienced, well known and respected Florentine artist by that time, particularly as he had traveled from Tuscany to Rome for the event.

In art history, he has generally been overshadowed by his younger contemporaries, Giotto (1267-1337) and Duccio (c.1255/60-1319). He was known as a master of mosaics, frescoes and paintings. It has been said of him, “Without Cimabue, there would have been no Giotto.” He is remembered as the man whose style inspired the movement that formed the Florentine School but the School is attributed to Giotto, as he carried it forward into the Renaissance. Cimabue is also known as Cenni di Pepo or Cenni de Pepi which translates to “bull-head” or “one who crushes the views of others”. A contemporary of his said in 1333 or 1334, “a nobler man than anyone knew, but he was, as a result—so haughty and proud that if someone pointed out any mistake or defect in his work, or if he noted any himself, he would immediately destroy the work no matter how precious it might be.” This information suggests he was a perfectionist and perhaps arrogant along with it. An example of his fresco work is the Madonna with Child Enthroned, Four Angels and St Francis which he painted in 1278-1280 and can be found in the transept of the Lower Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi.

Fun Fact: Dante, in the Divine Comedy, Canto XI, lines 94-96, in writing about pride, wrote of Cimabue: “In painting, Cimabue thought he held the field, and now it’s Giotto they acclaim—the former only keeps to shadowed fame.” This was written between 1308 and 1321, just a few short years after Cimabue had died. However, some 8 centuries later, Cimabue may well find himself in the limelight once again.

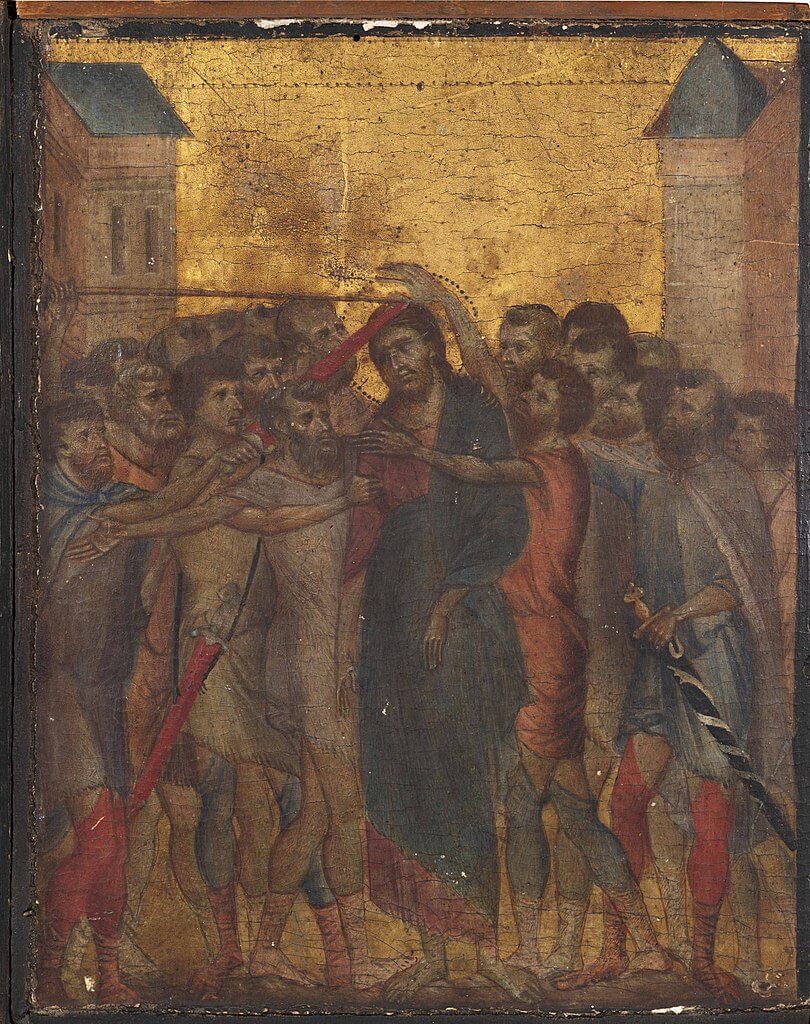

In 2019, a small painting was found in France, in the farmhouse of a woman who had retired. It had hung on the wall for years, thought to be a Greek icon. A sharp-eyed auctioneer noticed it and saved it from the rubbish. It was quickly identified as, Christ Mocked by Cimabue. Christ Mocked sold for $26.6 million in October, 2019, making it the most expensive painting sold from before 1500. Evidence was not only based on the painting style but also by the worm tunnels that matched up with the panels of wood of two other works by Cimabue: The Virgin and Child with two Angels in the National Gallery in London and The Flagellation of Christ in the Frick Collection in New York. The three paintings below are part of the Diptych of Devotion, which consisted of two doors with four paintings each. This means that the remaining five paintings are still missing today.

Where? Room 8 of the Uffizi Museum

When? 1465 Commissioned by? Uncertain. Originally, Giovanni de’ Medici ordered this painting to give it to the King of Naples, but this deal was abandoned due to a lack of funding for Filippo Lippi. What do you see? A praying Virgin Mary. Two angels are holding the child Jesus in front of Mary. Mary and Jesus both seem to be lost in their thoughts. Mary is depicted in a very elegant way compared to earlier paintings. For example, look at her sweet facial expression and the graceful veils and pearls in her hair. Notice also the halo above the heads of Mary and Jesus. These halos are just a simple circle and mark the transition between the solid gold disks used in earlier work and the disappearance of the halo in later Renaissance paintings. The angel on the right seems to giggle and watch the viewer directly in the eyes. Mary, Jesus, and the angels are depicted in front of a window, which can easily be mistaken for the frame of this painting. In the background, you can see a landscape inspired by Flemish paintings. Backstory: This painting was one of the first in which Mary and Jesus are depicted in a very human way. Mary is shown as an elegant young woman. This painting has served as an inspiration for many future paintings of Mary, but also for paintings of Venus, such as The Birth of Venus by Botticelli (a pupil of Filippo Lippi).

Symbolism: The pearls and veils that are carefully inserted in Mary’s hair and are gracefully draped around her neck are a new element that Lippi introduced to represent the elegance of Mary. The forehead is bigger than usual as the forehead was an object of beauty during that time (see the pearl on Mary’s forehead to emphasize this).

You can see the shadow of Mary in the window frame on the left. This is another example of a physical detail, whereas earlier paintings of Mary focused mainly of the spiritual symbols. However, you can also see a seashore in the landscape, which refers to one of Mary’s titles ‘port of salvation’. The rocks in the landscape refer to the biblical tale of Daniel. Finally, Mary is wearing a blue dress, representing her purity, virginity, and royalty. Who is Madonna? A Madonna is a representation of Mary with or without her child Jesus. Madonna comes from ‘ma donna’, which is Italian for ‘my lady’. In English, this is often referred to as ‘our lady’ and in French as ‘notre dame’. There are different types of Madonna painting. The ‘Madonna and child’ in Lippi's painting was a very popular subject during the Renaissance. Other types of Madonnas that have frequently been used in the art are, for example, the ‘Madonna enthroned’, ‘Madonna of humility’, ‘adoring Madonna’, and ‘nursing Madonna’. Why Madonna? The Madonna and child is the most popular theme in Christian art. Often Mary and Jesus are surrounded by angels or saints that pay their respects to them. Jesus and Mary are the most central figures in Catholicism, and their depiction should remind people of their religion. Who is Filippo Lippi? Filippo Lippi (1406-1469), also called Lippo Lippi, was born in Florence. He was the son of a butcher, but his parents died when he was still young. After his aunt took care of him for a few years, at age eight, he joined the convent of the Carmine where the friars took care of him. The friars discovered his love for art and gave him some great opportunities to pursue a career in art. His son, Filippino Lippi also became a famous painter (and is thought by some to be the model for the giggling angel in this painting). Sandro Botticelli is the most well-known pupil of Filippo Lippi. Another well-known work of Filippo Lippi in collaboration with Fra Angelico is the Adoration of the Magi in the National Gallery of Art.

Fun fact: Filippo Lippi was a Carmelite monk and was supposed to live a celibate life. However, he did not take the rules too strict as he was an extremely lustful man.

When he was in his 50s, he became the chaplain of a convent of nuns, and he fell in love with one of the nuns named Lucrezia Buti. He asked whether Lucrezia could serve as his model for Mary in this painting. This request was granted on the condition that there was always another nun present during these painting sessions. One day Lippi escaped together with Lucrezia from the convent (some stories tell that he abducted her) to live together with her. Together they got two sons. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas.

Where? Room 41 of the Uffizi Museum

When? 1505-1506 Created for? A wedding gift of Raphael to his friend Lorenzo Nasi. What do you see? This painting – also known as Madonna del Cardellino – shows the Virgin Mary (referred to as the Madonna), Jesus, and Saint John. Mary sits on a rock and wears a red dress with a blue mantle on top of it. She protectively watches the two children in front of her. Saint John, the boy on the left with the gold curly hair, is dressed in animal skins. He holds a goldfinch bird in his hand. He wants to give the goldfinch to Jesus who is touching the head of the bird. Jesus is close to his mother and places his foot affectionately on his mother’s foot. The three figures in this painting are shown in a pyramidal form – known as the Renaissance triangle – a popular composition in the early Renaissance to represent symmetry in a painting. In the background, you can see a blue and green landscape with bushes, trees, hills, a river, a bridge, a castle, and some houses. Backstory: Raphael created this work for his close friend Lorenzo Nasi, a wealthy wool merchant from Florence. The painting shows the meeting between Saint John, Jesus, and Mary. This scene is based on a medieval religious text, Meditationes Vitae Christi (see a later translation here), which describes the Holy Family meeting Saint John in the desert on their way back from Egypt (a story not mentioned in the Bible). The composition of the work was directly inspired by the painting Saint Veronica by Hans Memling, which was created between 1470 and 1475. The clothes of Mary, the composition, and the city in the background are all elements that can also be seen in Memling’s painting. Raphael's painting deteriorated severely over time, and in May 1999 it was taken down for restoration. It took almost ten years to finish the restoration. In the meanwhile, a much-lower-quality copy of the painting was on display in the Uffizi Museum.

Symbolism: The Virgin Mary is dressed in red and blue. Red is a symbol of the passion of Christ and blue is the symbol of the Church and of Mary. It was one of the more expensive pigments and therefore appropriate to use for an important figure like Mary.

The European goldfinch is associated with the crucifixion of Jesus. In this painting, Saint John passes the bird on to Jesus as a forewarning of his violent death. From the book that Mary is holding, experts have identified the words “Sedes Sapientiae”. This is one of the devotional titles given to Mary and means “seat of wisdom”. It emphasizes that Mary gave birth to Jesus (who represents wisdom). When Mary is depicted in the role of the “seat of wisdom”, she is typically shown seated on a throne with Jesus in her lap. However, in this case, the rock on which Mary sits serves as the throne. Flowers: Several flowers can be seen in the painting. While not all flowers have been identified conclusively, many believe the flowers to be: anemones (representing Mary’s sorrow for the passion of Jesus), daisies (representing the innocence of Baby Jesus), plantains (representing the path to follow Jesus), and violets (representing humility).

Who is Raphael? Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), popularly known as Raphael, was born in Urbino, a small city a few hours east of Florence. Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, he is considered one of the great masters of the Renaissance. He was a very talented architect, drawer, and painter, but is best known for his paintings of the Virgin Mary (called Madonnas) and his large-scale depictions of humans.

The Madonna of the Goldfinch was created during Raphael's period in Florence and shares many similarities with two other paintings of Raphael: the Madonna of the Meadow in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and La Belle Jardinière in the Louvre. A few years later, in 1508, he moved to Rome where he completed many works for the Pope, such as the Portrait of Leo X with Two Cardinals.

Fun fact: IIn 1547, the house of the Nasi family, which was several feet away from the Ponte Vecchio, collapsed. Two of the occupants were killed and much of its decorations got damaged. Raphael's painting was also badly damaged. Battista Nasi, the son of Lorenzo Nasi, did all he could to retrieve the remainings of this painting as it was a very valuable asset of his father.

The painting had broken into six large pieces and even more smaller pieces. Battista could recover most pieces, except one large piece from the bottom left corner. The painting was restored by Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, a good friend of Raphael. He did a great job in restoring the painting as this painting has become a very popular part of the Uffizi collection over the next centuries. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas

Where? Room 74 of the Uffizi Museum

When? 1534-1540 Commissioned by? Elena Baiardi for the funerary chapel of her husband Francesco Tagliaferri in Parma What do you see? Mary is holding the Baby Jesus. Mary has a very long, swan-like, neck. Notice also the length of her fingers and shoulders, and the oversized Jesus. These extended body features are typical of Mannerism. Mary’s beautiful hair is painted in detail as well as the pearls in her hair. She has bare feet and her right foot is resting on two beautiful green and orange pillows. On the left, six (somewhat eroticized) angels are all looking at different directions. Can you identify all six angels? In the bottom right, Saint Jerome (a well-known priest born in the fourth century) is depicted as a Greek statue. On the left, you can see the angel holding a large vase with the shadow of a cross painted on it. Backstory: This painting is also known as ‘Madonna of the Long Neck’ or ‘Madonna and Child with Angels and St. Jerome’. The painting is unfinished as Parmigianino died in 1540, which adds to the mystery of the painting. Quite some people say that Jesus already appears dead in this painting, something that could fit with the purpose of the painting to appear in a funerary chapel. Symbolism: Mary is wearing a blue robe, representing her purity, virginity, and royalty. On the right, the small figure of Saint Jerome is included, which was required by the commissioner for Saint Jerome’s connection to the worship of Mary. In hymns from the medieval times, the neck of Mary was compared to an ivory tower or column, which explains the presence of the exaggerated length of Mary’s neck as well as the columns on the right. Why Mary? Mary had a symbolic role of representing the church. This representation is in line with the analogy between the long neck of Mary and the ivory columns. The columns are also an architectural reference to the church. Who is Parmigianino? Parmigianino (1503-1540) was born in Parma (where he was named after, though his real name is Girolamo Francesco Mario Mazzola). He is known for his unorthodox and Mannerist painting style. Another well-known painting of Parmigianino is his self-portrait in a convex mirror which can be found in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Giorgio Vasari claimed that Parmigianino was an incarnation of Raphael (they both died at age 37). He is also known for his great etchings and woodcarvings.

What is Mannerism? This painting by Parmigianino is one of the prime examples of Mannerism. This style started in around 1520 at the end of the High Renaissance and lasted until about 1580 when the Baroque movement took over. In Mannerism ideals such as proportions, balance, and ideal beauty are violated on purpose. This style leads to paintings that are asymmetric and out of balance.

Fun fact: Just like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, Parmigianino found it difficult to finish his work due to his attention to detail. Indeed, several parts of this painting are unfinished, but we have a decent idea of what he intended to paint from the many surviving preliminary drawings that he created before starting with this painting.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster

Wai Laam Lo, CC BY-SA 3.0

Where? Room 18 of the Uffizi Museum

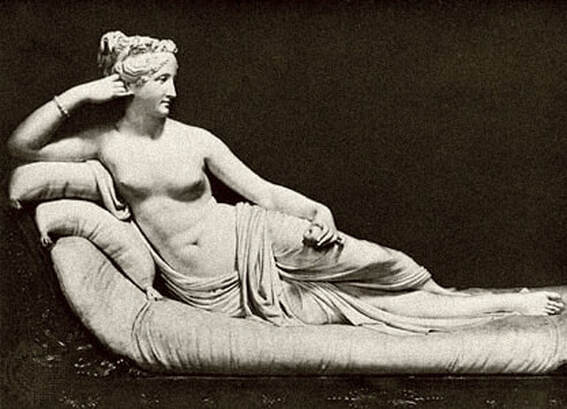

When? Between the third and first century before Christ Commissioned by? Unknown What do you see? A life-size marble statue (about five feet tall or 155cm) of the Greek goddess Venus. At her feet is Cupid (the god of Desire, erotic love, attraction, and affection) riding a dolphin. Venus is depicted in a fugitive pose after arising from the sea. The statue was considered one of the most erotic statues in the world due to her almost perfectly sculpted buttocks (which you cannot see, unfortunately). While her arms are partly covering her breasts and pubic area, it actually draws the attention to these parts of her body. Backstory: The origins of this statue are unknown, and thus we don’t know who sculpted her. It is the oldest statue in the Uffizi and is referred to as Venus de’ Medici because the Medici family acquired it in 1677. The statue was initially displayed in Rome, but Pope Innocent XI decided that it should be moved to Florence. Pope Innocent XI was a deeply religious man and decided that such a notorious naked statue did not belong in Rome. The statue was originally colored. However, over time the statue lost its color and experts thought that the colors were not part of the original. So, in the 18th-century acids were used to remove the last traces of color from the statue. Recent microscopic research has shown that the statue was colored originally. The original color of her hair was gold, she had red lips and her ears were pierced for earrings. This marble statue is a copy of an original Greek statue of Venus in bronze. The Venus De’ Medici is one of the most copied statues of all time (for example, there is one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York). Interestingly, the Venus de’ Medici, with Cupid riding a dolphin is not tied to any known mythological story, which adds to the fascination and speculation about this statue. Symbolism: The size of Venus is enormous compared to the small Cupid and the dolphin at her feet to give the impression that Venus is giant. The somewhat apologetic pose of Venus (covering her breasts and pubic area) and the dolphin at her feet make it likely that she got somewhat surprised when arising from the sea. Who is Venus? Venus is the Roman goddess of love, beauty, sex, fertility, prosperity, and desire. Venus is also known in the Greek mythology as Aphrodite. Together with the Mars, the god of war, she is the parent of Cupid. The ancient Romans also considered Venus as the goddess of the gardens, and this makes her a popular subject for statues placed in gardens. Over time many statues have been made of Venus, often as an excuse to depict nudity. A well-known example is the Venus Victrix of Antonio Canova which can be admired nowadays in the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

Why Venus? Venus was admired by the Romans and Greeks as she represented love and sexuality. This statue of Venus was heavily inspired by the life-size statue Aphrodite of Cnidus (or Knidos), a famous statue from the fourth century before Christ. These life-size statues of a naked Venus were considered to be very attractive to men in ancient times.

Fun fact: The statue has an inscription at its base reading ‘CLEOMENES SON OF APOLLODORUS OF ATHENS’. However, this inscription is not original as the base with the inscription was broken. The current inscription was added to it in the 17th century. It seems highly unlikely that Cleomenes created this sculpture as he was not a very good sculptor. In the 17th and 18th century it was common practice to add the name of Cleomenes to statues of mediocre quality to enhance the value of those statues. The Venus de’ Medici sculpture, however, is more in line with the work of Praxiteles who created very elegant and graceful statues around the time that this statue was made, but there is not much other evidence to confirm this.

Written by Eelco Kappe

Where? Room 8 of the Uffizi Museum

When? Between 1435 and 1460. The dating of this painting has been the subject of much debate, but most critics believe it is painted between 1435 and 1440. Commissioned by? Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni, a rich Florentine man who had a strong commercial interest in the battle of San Romano. What do you see? This painting shows a scene from the battle of San Romano on June 1, 1432. This battle was fought between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies. The central figure on the white horse is probably Bernardino della Ciarda. He was a former captain in the Florentine army but had recently defected to the opponents. He is fully armored and about to be thrown off his horse by a jousting lance. In the foreground, you can see several fallen horses and soldiers. The composition of the painting is not very realistic as the horses and soldiers in this painting look like dummies. The reason is that Uccello’s main interest in painting was not to perfectly depict a scene from history, but he was more interested in getting the linear perspective right. Look, for example at all the lances that are in this painting. Some are conveniently dropped on the ground in a geometrical pattern. The lances in vertical direction all point to the same vanishing point which Uccello wanted to incorporate to create depth in the painting. The vanishing point is just above the head of the white horse. In the background, you can see some soldiers and dogs hunting for rabbit and deer. Backstory: The battle of San Romano (a small place in Italy, near Lucca) was part of the war between the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Lucca with its allies from Genoa, Milan, and Siena. An important element of the war was about who would get access to the port of Pisa for trade. The battle of San Romano took place on June 1, 1432, and lasted less than a day. This battle was only a relatively minor battle, but the Florentines remembered it as a turning point in the war. This painting commemorates the Florentine victory in this battle, though Sienese sources disagree with this conclusion. The battle started when Florentine general Niccoló Tolentino was attacked after he was separated from most of his army when he was exploring the area. Tolentino and his small group of soldiers fought a brave fight and did not give up until another Florentine general, Micheletto Attendolo (who is at the center of the Louvre version of this battle), arrived at the battle scene with reinforcements. Attendolo and his army helped Florence to win this battle. The war dragged on for another year without a clear winner and in the end the war was settled through negotiations. Other versions of this painting? This painting is a part of a triptych (a work of art divided into three parts) made by Uccello. The three paintings represent different moments in the battle of San Romano. There are two alternative explanations about the order of the paintings. The simple explanation is that the three paintings represent the morning of the fight (the version in the National Gallery in London), the afternoon (the current version), and the evening (the Louvre version). A more popular alternative is that the National Gallery version represents the beginning of the battle with Niccoló da Tolentino. The Louvre version represents the arrival of Micheletto Attendolo and his army, and the current version shows the last episode where Bernardino della Ciarda from the opposing army was unhorsed. Note that the current painting of the battle in the Uffizi is the only of the three versions that is signed (see the words PAVLI VGIELI OPVS in the shield at the bottom left).

Who is Uccello? Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) was born as Paolo di Dono in Pratovecchio in Tuscany. In his teenage years, he was an apprentice of Lorenzo Ghiberti and later he got influenced by contemporaries such as Donatello, Brunelleschi, and Masaccio. He was named Uccello, which is Italian for ‘bird’, because he liked to paint birds. He developed strong scientific interests and was very interested in representing perspective in paintings, something that he and contemporary artists just introduced to painting.

The appropriate use of linear perspective was often more important for Uccello than what the painting should represent. In his paintings, he combines elements of the older Gothic tradition (the decorative parts) and the newer Renaissance movement (which introduced depth and perspective). Linear Perspective? Linear perspective was developed around 1420 by Brunelleschi. It was a completely new approach to represent space in paintings. The simplest idea of perspective is that the size of objects becomes smaller the further away they are from the observer. Paintings with perspective have one or multiple vanishing points which help the painter to create perspective. Foreshortening is a specific form of perspective in which an illusionary trick is used to provide the idea of depth. A great example is when someone wants to paint a picture of a person laying with his feet towards you. To create the idea of depth, the painter will paint the feet of the person bigger than his head. The Lamentation of Christ by Mantegna is a great example of foreshortening. Note that the linear perspective in Uccello’s paintings is not perfect, but it did help to create depth in two-dimensional paintings. His work served as an inspiration for many artists in the next generations who perfected his ideas about linear perspective in paintings.

Fun fact: This painting of Uccello and its two companion pieces in the Louvre and National Gallery originally had an arched top, possibly a Gothic arch. However, these arches have been cut away around the time that Lorenzo the Medici seized the paintings from the commissioning Salimbeni family. The paintings were changed into rectangular formats and some additions were made to the top corners.

There is clear evidence that the top left and right corner did not originally exist, but these additions were made at the end of the 15th century. It is very unlikely that Uccello made these additions, but the unknown artist that made these did a good job as the additions are very hard to notice with the naked eye. An analysis of the different layers for these additions, however, clearly reveals that some different materials and paint compositions are used.

Where? Room 41 of the Uffizi Museum

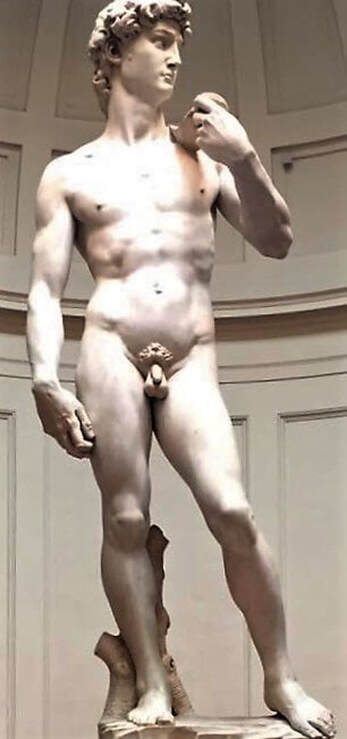

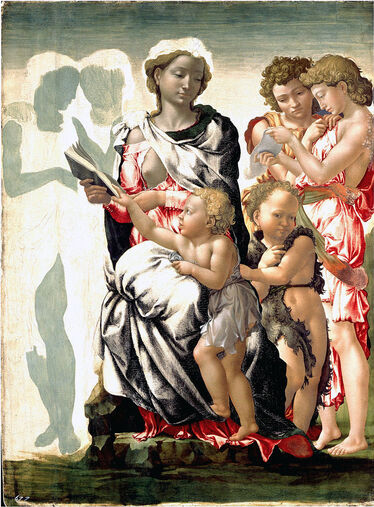

When? 1506-1508 Commissioned by? Agnolo Doni to celebrate his marriage with Maddelena Strozzi (from the powerful Strozzi family). What do you see? Mary, Joseph, and Baby Jesus are shown in the center. Mary is sitting on her knees and looks up to Jesus while handing Jesus to Joseph. On the right, a young John the Baptist is depicted and in the background a group of five young and naked people. Look at the body of Mary, which is partly turned around in a somewhat unnatural pose. This painting has been influential for future work and has been labeled as one of the foundations of Mannerism, which is an art style in which ideas such as proportions, balance, and ideal beauty are violated on purpose. Look also at the frame, which contains five carved heads. The head of Jesus is on top, and the other four heads represent the four prophets that told about the coming of the Messiah. This painting stands out because of its bright colors, which are due to the tempera pigment used by Michelangelo. This pigment typically keeps its color over time.

John the Baptist (the patron saint of Florence) is strategically posed in between the Holy Family and the pagan people in the background to bridge the gap between both worlds.

In front of John the Baptist, there is a plant that is a combination of a hyssop (a symbol of the humility of Christ and baptism) and a cornflower (a symbol of Christ symbolizing heaven). The clover in the foreground represents the Trinity (God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit). The carvings on the frame include crescent moons, lion heads, stars, and vegetation, and are believed to refer to the Doni and Strozzi families. Who is Doni Tondo? Agnolo Doni was a wealthy Florentine banker. The word ‘tondo’ was used to refer to a circular work of art. Tondo is derived from the Italian word ‘rotondo’, which means round. The term ‘tondo’ is typically only used for large round paintings (over two feet in diameter). Why the Holy Family? The Holy Family is a model for Christian families. The Holy Family is depicted in two different ways. Most commonly, it consists of Jesus of Nazareth, his mother, the Virgin Mary, and his foster father, Saint Joseph. However, there are also other versions in which Saint Joseph is replaced by Saint Anne, the mother of Mary. Who is Michelangelo? Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475-1564) was an architect, engineer, painter, poet, and sculptor. He is considered to be one of the greatest artists ever and was considered the best artist of his time. He is probably most well-known for his sculptures (think about the David and the Pietà) and his frescos at the Sistine Chapel. Fun fact: This is the only finished panel painting by Michelangelo that exists nowadays. In the National Gallery in London, there are two other panel paintings of Michelangelo, The Entombment and The Virgin and Child with Saint John and Angels, but he did not finish these paintings. Michelangelo was quite good in not finishing his work, as can be seen by the fascinating series of unfinished sculptures in the Galleria Accademia. Of course, Michelangelo has also painted frescos, like the famous ones in the Sistine Chapel. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas.

Where? Room 41 of the Uffizi Museum

When? 1517-1519 Commissioned by? Pope Leo X What do you see? The portrait of Pope Leo X, shows the Pope sitting in his study. He is depicted realistically in a three-quarter profile. He wears the papal robe and the papal camauro, a cap traditionally worn by the pope. A cardinal is on both sides of him. Their silence helps to establish the authority of Pope Leo X in this painting. All three are wearing velvet (a woven fabric with evenly distributed patterns), and the Pope is also wearing a so-called, damask undergarment that shines in the light and has fur linings.

Backstory: Raphael was the lead painter for Pope Leo X and he had already made quite some portraits of Pope Leo X in fresco scenes. He also painted several portraits of Leo X to distribute throughout Italy. The current painting is the most well-known of these different portraits. The idea behind distributing these paintings was to promote the Medici regime throughout the country. This was important as a lot of things were happening in those years that created uncertainty for the common people and their leaders. One of these things was that Martin Luther (a famous German theology professor) publicized his famous list of complaints against the Roman Catholic Church.

Between 1513 and 1605, four popes came from the Medici family. An important reason for this is that popes liked to appoint their family members as cardinals, making it more likely that they would eventually become pope. The cardinal on the left of the painting is Giulio di Giuliano de’ Medici (a cousin of the Pope who would become Pope Clement VII from 1523 until 1534). The cardinal on the right is Luigi de’ Rossi (another cousin of the Pope).

Who is Pope Leo X? Giovanni de’ Medici (1475 – 1521) is the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, the ruler of the Florentine Republic. He became a cardinal at 13 years old. An important reason that Giovanni became a cardinal at such a young age was that his sister was married to Pope Innocent VIII. He became pope on March 9, 1513, until his death on December 1, 1521.

During his rule as pope, Leo X excommunicated Martin Luther from the church, and he granted people who donated to the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica a reduction in the amount of punishment they would have to undergo for their sins (called indulgence). He was a big spender and ruined the papal finances under the motto: “Since God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it”. Who is Raphael? Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), popularly known as Raphael, was born in Urbino, a small city a few hours east of Florence. His father, Giovanni Santi, was a painter with a good reputation, but Raphael had already lost both his parents at age 11. Raphael is best known for his depictions of the Virgin Mary (Madonnas), and his large-scale depictions of humans. His work is widely appreciated for the clarity and magnificence with which he could paint people and his simple compositions. In 1508, he was summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II, the predecessor of Pope Leo X, to become the lead court painter. He stayed there until his death, which was one year before the death of Pope Leo X. He is buried in the Pantheon in Rome.

|

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us