|

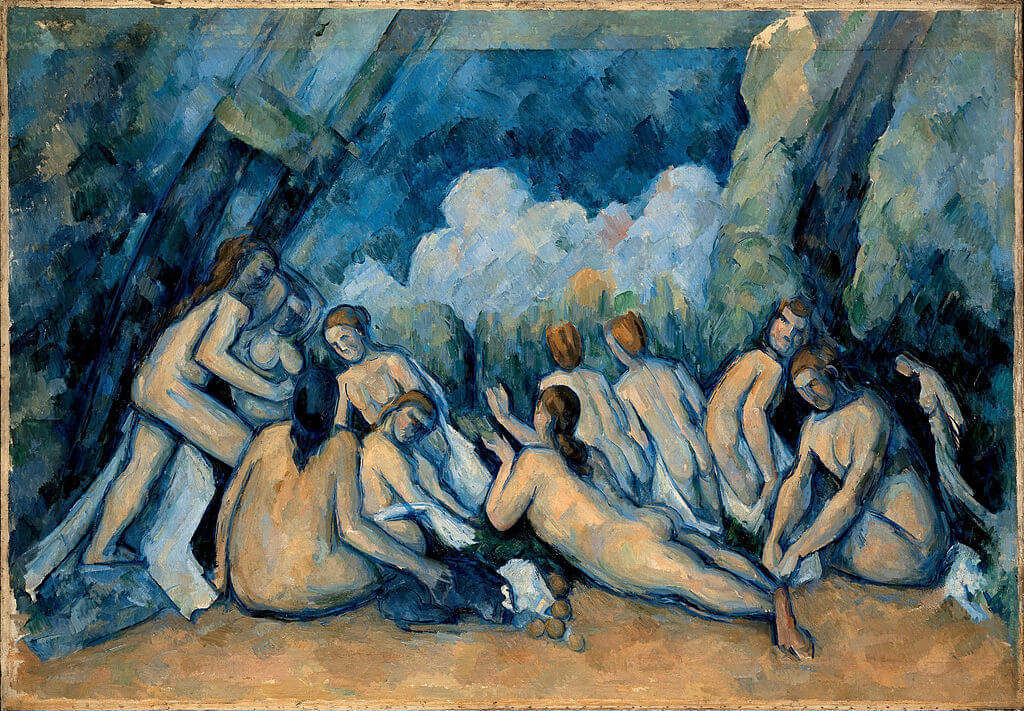

Where? Gallery 164 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

When? 1898-1905 What do you see? A group of women bathing near a river. There are two groups of women in the foreground; a group of six women on the left and a group of eight women on the right. In the middle of these two groups, you can see a river with someone swimming in it and on the other side of the river you can see the back of a man walking with a horse beside him. In the background, we can see a landscape with large cypresses, a church tower, and a blue sky with clouds. The middle of the painting has its own frame, bounded by the trees that are growing towards each other. Looking in more detail, the bodies of the women in this painting are not very realistic. They are malformed (look for example at the incorrect proportions of the tall woman standing on the left). In addition, none of the women in this painting has an identifiable face. Also, quite some parts of the human bodies are unfinished, and we can see the canvas underneath. For example, look at the horse or the woman lying on the right with her feet almost sticking out of the bottom of the canvas. Cézanne is showing the women more abstractly, and this painting had a big influence on the abstract paintings later in the 20th century. Backstory: Paul Cézanne worked for many years on this painting, and it was still unfinished when he died in 1906. He did not use any models for this painting but rather painted them from his imagination. During his life, he created about 200 paintings and drawings of nude bathers, but this painting is generally considered to be his best. Another version of the Bathers, painted around the same period as the painting in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is in the National Gallery in London. The Metropolitan Museum of Art owns a much earlier version of Bathers, which was created between 1874 and 1875 and shows them in a more typical impressionist style.

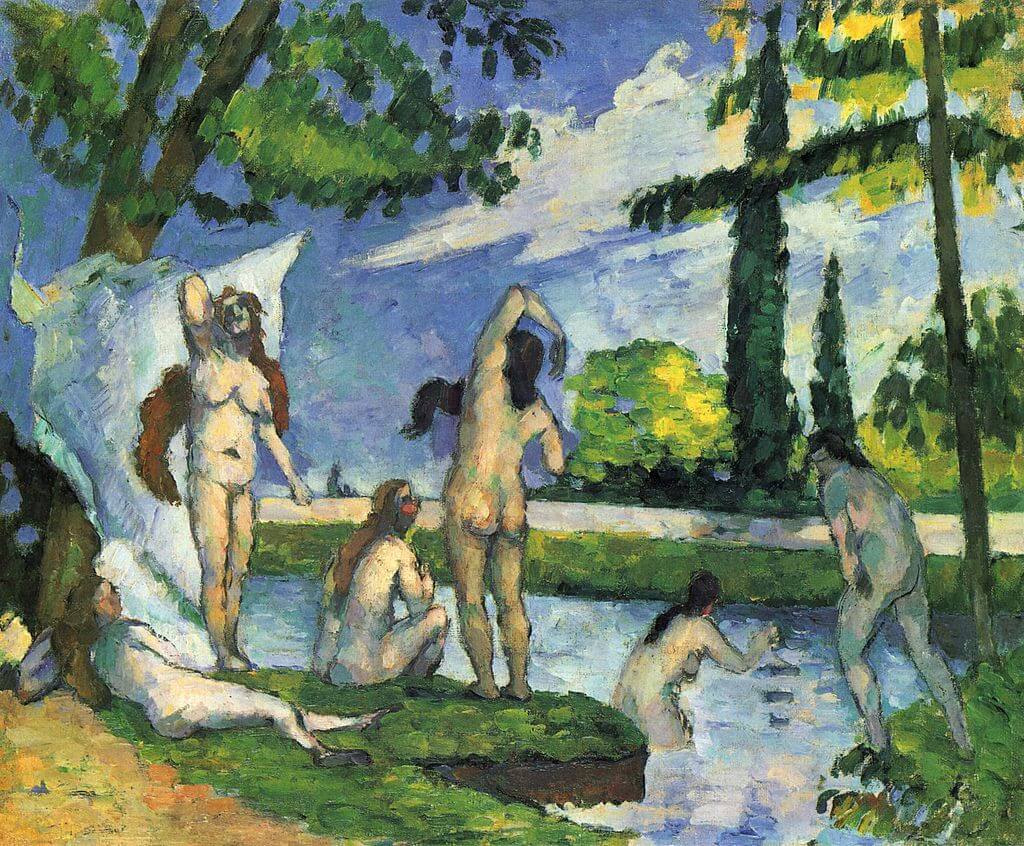

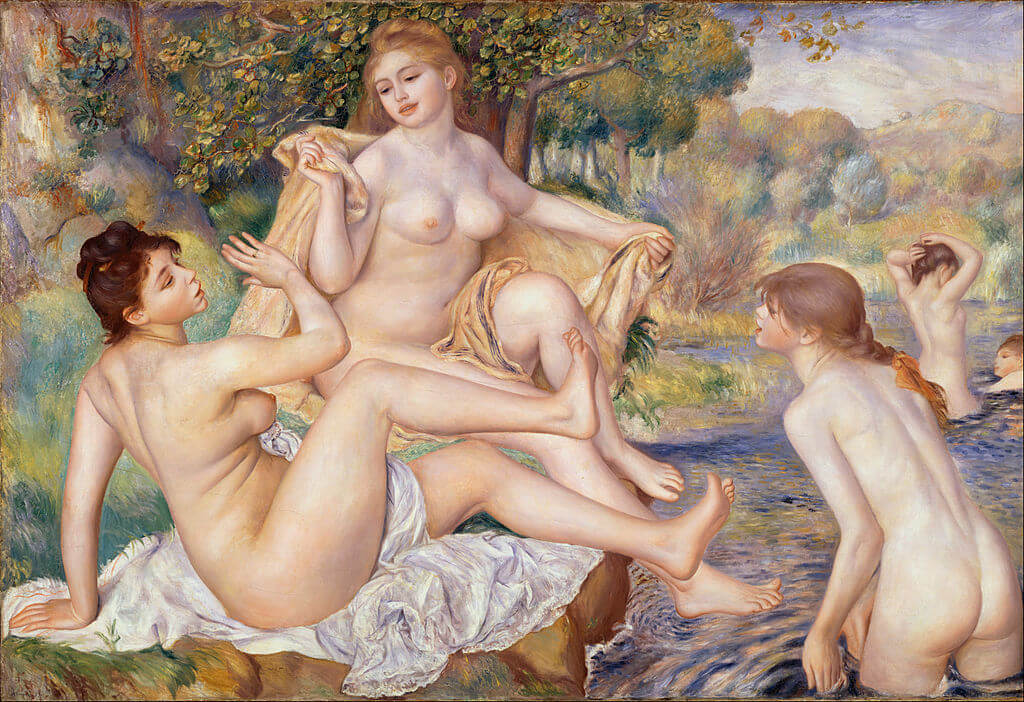

Bathers in art: This painting of Cézanne combines a landscape of Aix-en-Provence in the South of France with a classical bathing scene. It shows some similarities to the painting of Diana and Actaeon by Titian which also contains a bathing scene. Titian depicted the group of bathers in a triangular composition, which is also true for the two groups of bathers in Cézanne’s painting (as well as the large triangle formed by the trees). Finally, both paintings have some opening in the middle in which we can see a distant landscape. Bathers have been a subject that has inspired more painters over time. For example, the Philadelphia Museum of Art also shows a painting entitled The Large Bathers by Renoir.

Who is Cézanne? Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) was born in Aix-en-Provence in 1839 and also died there in 1906. In his twenties and thirties, Cézanne spent considerable time living in Paris, where he developed a friendship with Camille Pissarro. The father of Paul Cézanne was a banker and financially supported him during his life, such that he could focus completely on his art. He was an Impressionist painter, but later in his life, he developed some more abstract paintings. Picasso and Matisse were heavily influenced by this later work of Cézanne and considered him to be ‘the father of us all’.

Fun fact: This painting of The Large Bathers is considered to be the best work by Cézanne. The painting has had a big impact on many future artists. Cézanne painted this at the end of his life and it was still unfinished when he died at age 76. It is not very common that painters create their masterpieces at the end of their career. According to academic research, painters peak at the age of 42. In other words, painters create their masterpieces, on average, at the age of 42, and after that, the quality of their work generally decreases. The reason is that the creativity of artists decreases at a higher age and when they get old they are also often limited by physical ailments. For example, Sandro Botticelli created his masterpieces The Birth of Venus and La Primavera when he was between 35 and 41 years old, and he only died at age 64.

Written by Eelco Kappe

0 Comments

Where?

What do you see? A young dancer of fourteen years old is shown at 70 percent of her real size (the sculpture is a bit taller than 3 foot or about 1 meter). She seems relaxed and is standing in ballet’s fourth position (there are seven positions for the feet in ballet, and the ballerina here has her feet in open fourth position – about 12 inches apart and facing different directions). The girl is sculpted realistically and Degas intends to show the hard life of a ballet dancer and what it does to her body. Her back leg supports most of her weight. She has thin legs and arms, holds her arms behind her back, and has her hands clasped together. She confidently holds up her chin, pushes her shoulders back, and her eyes are half closed. She wears ballet shoes, a real tutu made of tarlatan, and a gold-colored bodice (a vest) made of linen. The girl also wears a real ribbon in her plaited hair. Degas used real hair for this sculpture, which he covered in wax.

Copies: The National Gallery of Art holds two statues (the original wax statue and a bronze casting) of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen as well as two nude studies for this statue. When Degas died, about 150 statues were found in his studio of which only one of the versions in the National Gallery of Art had been shown to the public at an exhibition. Many of these statues were in bad shape, but about half of these statues were repaired after his death. The National Gallery of Art has many of these original statues.

The surviving family of Degas decided to create about 22 bronze casts of these statues. Because of this, nowadays, bronze copies of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen can be found in many other locations besides the ones mentioned on the top. For example, the statue is also in the the Art Institute of Chicago, Harvard Art Museums, Metropolitan Museum of Art (currently not on view), and the Norton Simon Museum. One of the bronze copies of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen was sold in 2009 for $19 million.

Who is Degas? Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas (1834-1917) was born in Paris. Whereas he spent most of his life in Paris, he also lived for three years in Italy and spent time in Florence, Naples, and Rome. He started as a more traditional painter by creating historical stories and portraits, but during the 1860s he changed his style and became one of the founders of Impressionism, together with artists like Cézanne, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, and Renoir.

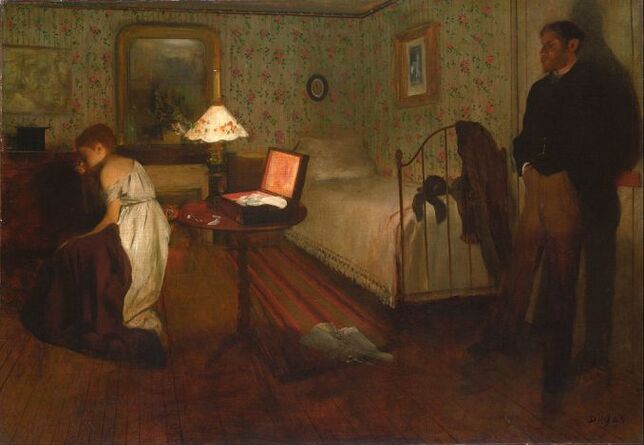

Later on, he changed his focus and started to paint scenes from everyday life with a particular interest in dancers, theater, and horse racing. He moved on to focus on more realistic paintings, and one such example is Interior in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He made statues mainly as training to understand the anatomy and movements of people.

Fun fact: When Degas showed this sculpture at an Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1881, many people did not like it at all. For example, some people called the sculpture a monkey. It also did not help that the sculpture was on display in a glass vitrine. Sculptures typically were idealized versions of well-known people created in marble. Instead, Degas created an unknown young girl from Paris, and the girl did not look at all like a goddess. On top of that, he created this sculpture from beeswax and he added objects like a tutu to the statue. Because of the negative reactions Degas got, he removed the statue from the exhibition and stored it in his studio until his death.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Canvas or statue (Amazon links).

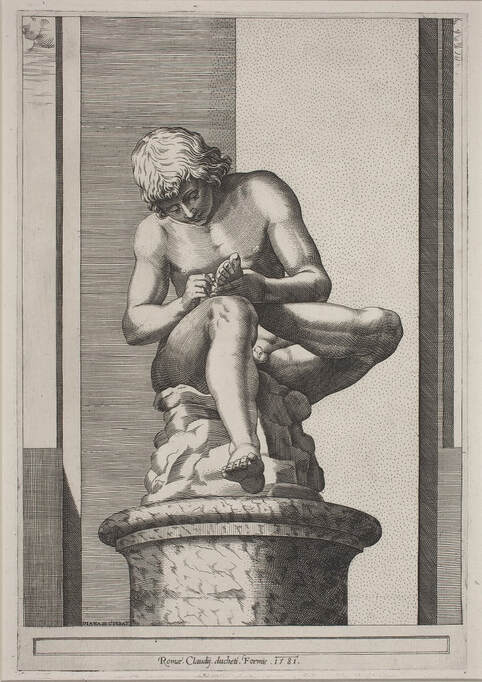

Where? Prints are part of the collections of several museum around the world, including the Ashmolean Museum, National Gallery of Art, National Galleries Scotland, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Rijksmuseum.

When? 1581 What? Engraving on laid paper: plate: 30.6 x 20.8 cm; sheet: 54.2 x 42.9 cm. What do you see? A young nude boy sits on a pile of rocks, intently focused on removing a thorn from his bare foot. The statue sits in the corner of a room or foyer. Puffy clouds visible in the upper part of the window on the left help to define the available light source. Engraving techniques produce the textures that indicate the depth of the walls and the space the statue occupies. Each shadow is created by a multitude of fine lines, overlapping lines, and cross-hatching. The marble pedestal supporting the statue raises the young boy so the viewer can see the scene from below. His right foot does not touch the ground or rest as he tries to remove this thorn without inflicting more pain. The story and original sculpture date back to a Classical Roman marble that is said to be a copy of an even earlier Grecian bronze rendition lost in the 3rd century B.C. Reproductions of the statue were one of Rome's most widely admired antiquities, and drawings and prints were popular and in demand. A copy of the original ancient statue can be found at Palazzo dei Conservatori, which is part of the Capitoline Museums in Rome. It is recorded as having been there since 1499-1500. The Crucifixion, with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist Mourning by Rogier van der Weyden2/26/2020

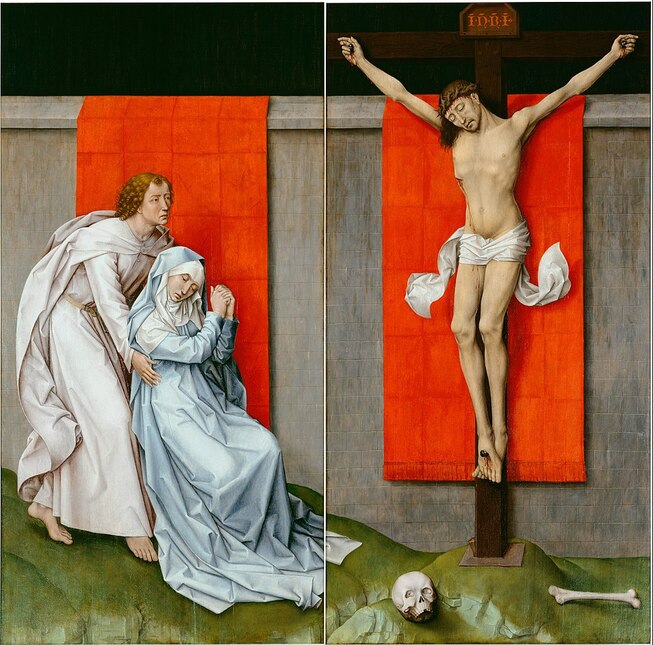

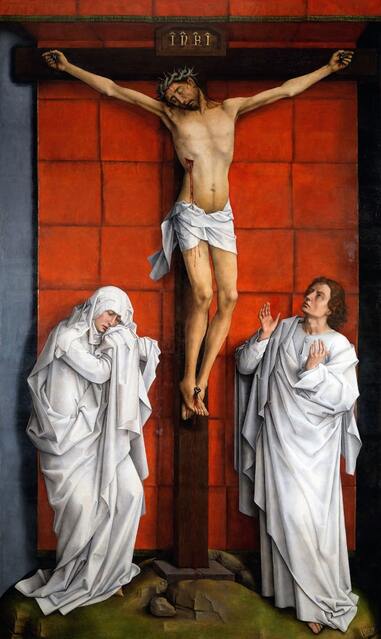

Where? Gallery 306 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

When? About 1460 Commissioned by? Unknown What do you see?

Symbolism: The skull and the bone refer to Golgotha which means ‘place of the skull’ and was the hill where the crucifixion of Jesus took place. The vermillion banners refer to the blood of Jesus. The dark sky refers to the three hours of darkness during the crucifixion. This darkness is described in Matthew 27:45, Mark 15:33, and Luke 23:44. After the darkness ended, Jesus died. Interestingly, John the Evangelist, probably the writer of the Gospel of John, is the only gospel writer who does not refer to this darkness during the crucifixion.

Who is Van der Weyden? Rogier van der Weyden, also known as Roger de la Pasture, was born in 1399/1400 in Tournai, Belgium. When he was about 36 years old, he moved to Brussels, where he probably lived until he died in 1464. Many of his surviving works are altarpieces, triptychs, diptychs, or portraits. He was a popular painter during his lifetime and received many international commissions for his work, which was rare for that time. Together with Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck, Van der Weyden is considered to be the most influential 15th-century painter from the Northern part of Europe. Van der Weyden was an innovative painter. He was one of the first to include commissioners of his work as participants in the religious scenes that he painted. He also stood out from other painters by including the emotions of his subjects into the painting. One of his masterpieces is The Descent of the Cross in the Prado Museum in Madrid.

Fun fact: This painting is on display at the end of European Art between 1100 and 1500 section on the second floor of the East Wing of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. So, you will have to work your way through a minimum of four other rooms with art from the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance before you can truly admire the painting. However, the Philadelphia Museum of Art has constructed their rooms in such a way that you can already catch glimpses of Van der Weyden’s masterpiece from the central hallway (about 250 feet away). The iconic red of Van der Weyden’s large diptych attracts people from a long distance to have a closer look at it.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas

Where? Gallery 165 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

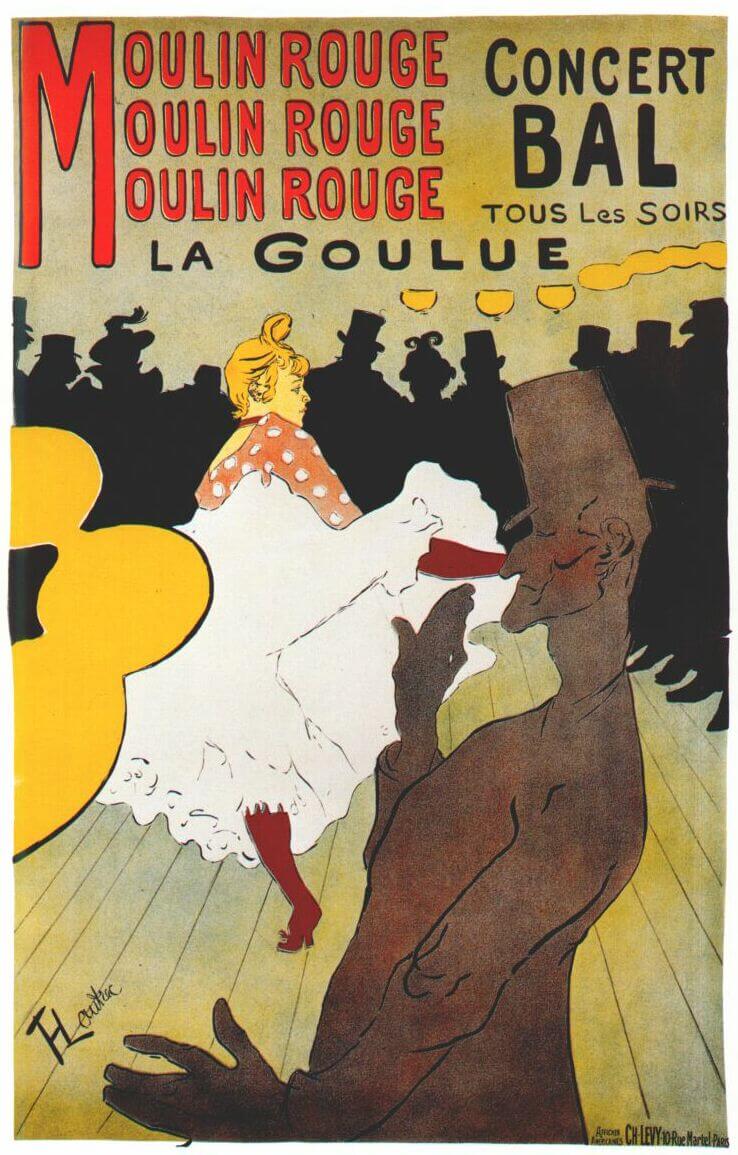

When? 1890 What do you see? The couple in the middle is dancing the can-can in the Moulin Rouge. The man is dressed in a black suit with a black top hat. The woman wears a beige-orange dress with red socks. The man teaches the woman some new moves of the can-can dance. In the foreground is an mysterious, unknown woman in an elegant pink dress. A group of dressed-up people, most of which are men, surrounds the dancing couple. These people engage in conversations, look at the dancing couple, or just hang out on the bar in the background. Toulouse-Lautrec knew most of the people in the Moulin Rouge as he was a regular there. Toulouse-Lautrec used a combination of plain colors with some bright colors to take the viewer on a journey through the Moulin Rouge. Most viewers start by looking at the woman in pink in the foreground, look at the dancing couple next, and then look at the man in the bright red jacket in the background. The light in this painting is provided by the electric chandeliers on the ceiling. This painting is lauded for its beautiful composition. Backstory: After Toulouse-Lautrec completed the painting, the owners of the Moulin Rouge bought it and put it on display on top of the bar. An inscription on the back of this painting reads: “The instruction of the new ones by Valentine the Boneless.” This identified the dancing man as Valentin le Désossé (which means ‘the boneless’). He was a star can-can dancer at the Moulin Rouge. Valentin le Désossé was the stage name of Jacques Renaudin. He had a slim build with long arms and legs, giving him the perfect body for a can-can dancer. He was very elastic and could perform the expressive can-can dance moves with unequalled grace. He did not accept money for his dance performances as he did it for the love of dancing. The woman dancing with Valentine is Louis Weber, a popular dancer from that period. She was so flexible that she could keep her body straight while standing on a single leg and with the other leg raised above her head. What is the Moulin Rouge? The Moulin Rouge is a cabaret and nightclub in Paris established in 1889. As its French name suggests, the Moulin Rouge is a building with a large red windmill on top of it. It is the birthplace of the modern can-can dance. The Moulin Rouge provided entertainment for all layers of society. The extravagant shows, innovative and unique interior, and the world-famous dancers performing there were the key ingredients for the immediate and lasting success of this place. Below is an image of an 1891 poster to advertise the Moulin Rouge by Toulouse-Lautrec. The Moulin Rouge is still open to visitors today.

What is the can-can dance? The can-can (or cancan) is a dance developed in France in the first half of the 19th century. It is a high-energy dance originally performed by both sexes. It involved kicking the legs above the head, splits, and cartwheels (check out this video). It developed over time into a dance mainly performed by women. The female dancers used an elaborate and provoking routine with their long skirts.

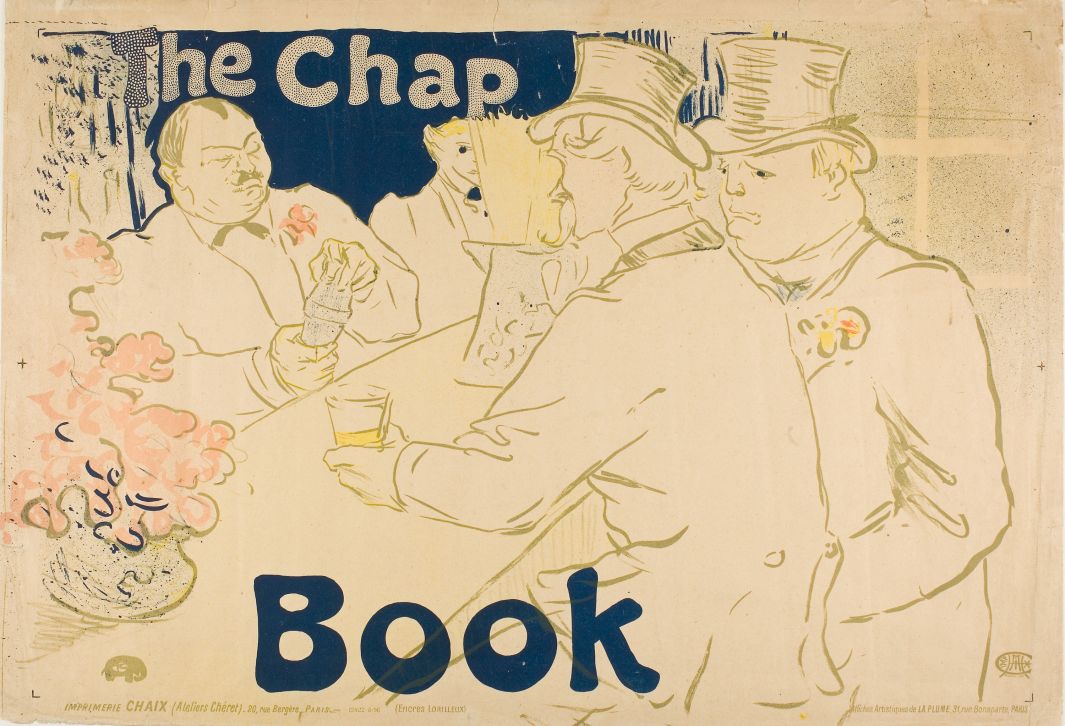

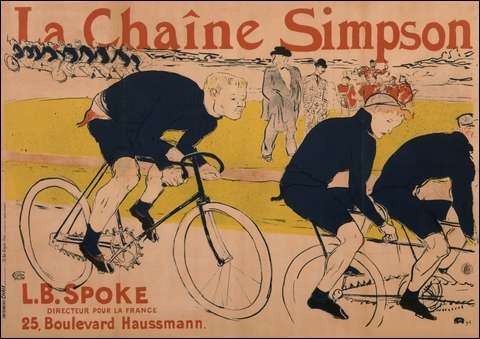

In the 19th century, the can-can was considered a scandalous dance and it was often performed by prostitutes. However, its status improved over time and by the time the Moulin Rouge opened, there were professional can-can dancers that could make could make a living dancing full-time. Who is Toulouse-Lautrec? Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (1864-1901) was born in the South of France and was the first child of a wealthy family. From a young age, his artistic skills were present, and he developed himself into a very productive artist. Toulouse-Lautrec is an important representative of the Post-Impressionist art movement, together with artists like Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, and Van Gogh. Unlike some of these other painters, Toulouse-Lautrec could sustain himself by making advertising posters for nightclubs and other businesses. Two of those posters are shown below. The first is an 1895 advertisement for the American literary magazine The Chap-Book. The second poster is from 1900 and advertises a Simpson bicycle chain.

Fun fact: The parents of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec were first cousins and as a result Toulouse-Lautrec suffered from serious health problems throughout his life. One health problem he faced was that his legs stopped growing as a child and, as a result, he became only 4 ft 8 in (1.42) tall.

His atypical stature (the legs of a child combined with the torso of an adult) led to a lot of mockery from other people and Toulouse-Lautrec resorted to drinking a lot of alcohol. To make sure that he always had a supply of alcohol with him, he had a hollow cane – which he needed to walk – filled with alcohol. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas

Where? Gallery 153 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

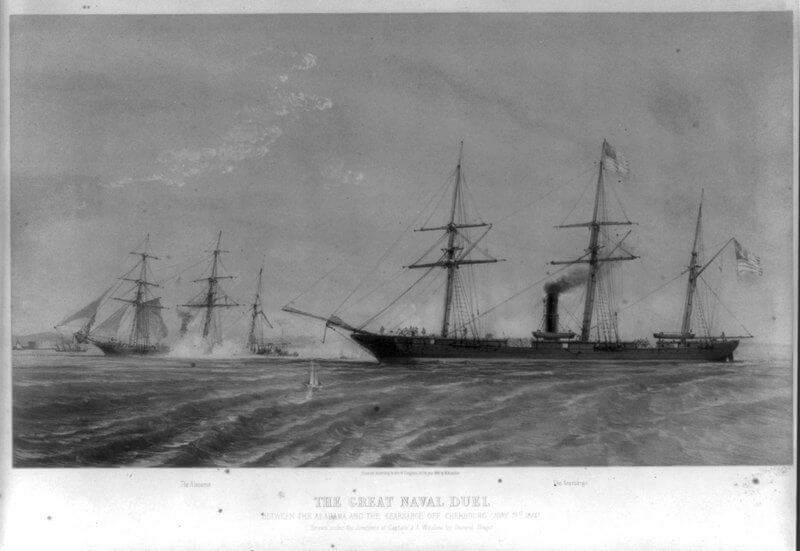

When? 1864 What do you see? Looking from a boat on the sea, we can see a green and blue rocky sea that makes up most of the painting. The large ship in the center background is the CSS Alabama. A lot of smoke is rising from the ship as the USS Kearsarge has just hit its engine. The rear of the ship is already sinking. Crew members of the ship are jumping into a small lifeboat in front of it. On the left side, behind the CSS Alabama, you can see part of the USS Kearsarge. We can see the U.S. flag on the top left, but most of the Kearsarge is hidden behind the smoke. The boat on the top right is the Deerhound. It is an English ship that is on its way to rescue some of the survivors on the CSS Alabama. It carries a red flag to indicate that it belongs to the British Royal Mersey Yacht Club. The small boat in the foreground is a French pilot boat, Les Deux Jeunes Soeurs, which is also on its way to rescue some of the survivors from the CSS Alabama. The boat has three flags: A French flag in the back, a regulation blue and white flag of pilot boats in the middle, and a white flag in the front to indicate that it is neutral in this conflict. It also carries a small boat to rescue more people. To the right of this ship is a mast in the water with a surviving sailor holding on. Backstory: During the American Civil war, the Confederate States had no navy to defend themselves against the Union States. The Union States blocked the export of cotton by ship from the Confederate States, and so the Confederate States decided to buy a series of warships from England. The CSS Alabama was a ship of the Confederates and was built in 1862. In its first two years, it had already sunk 65 ships of the Unionists throughout the world. On June 11, 1864, the ship anchored at the entrance of the harbor of Cherbourg, in the North of France. On June 19, 1864, the CSS Alabama got into a fight with a warship of the Union States, the USS Kearsarge. While the CSS Alabama had heavier firepower, the USS Kearsarge was a more advanced ship with more precise firepower. Thousands of French spectators witnessed the fight between the two ships from the coast, and the USS Kearsarge defeated the CSS Alabama, which sank. The fight was widely covered in the newspapers, as can be seen by the illustration below in the Illustrated London News.

The American Civil War: The American Civil War took place between 1861 and 1865 in the United States during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln. It was a war between the Confederate States, representing the Southern states of the U.S., and the Union, representing the other U.S. states. The Confederate States were supporting slavery, while the Union States followed the U.S. Constitution and were against slavery. The Union States won the war, and the slaves in the South were freed. About 700,000 people died during this war.

Who is Manet? Édouard Manet was born in 1832 in Paris and died there in 1883. When Manet was 18 years old, he spent about one year on a ship going to Brazil. While he failed the examination for the naval academy, he remained always fascinated by the sea. About ten percent of his paintings were about the sea, including Rochefort’s Escape in the Kunsthaus Zurich. Manet is also the principal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism. During the 1860s, he became friends with painters such as Cézanne, Degas, Monet, Pissarro, and Renoir, and under the lead of Manet, they developed the Impressionist art style. An example of an Impressionist painting by Manet from 1878 is The Rue Mosnier with Flags in the Getty Museum.

Fun fact: Manet did not witness the fight himself. He learned about it from the newspapers which were full of information and drawings about this fight. Within 26 days of this fight, this painting by Manet was already exhibited.

It is likely that Manet did not know the details about the USS Kearsarge and that this was the reason that he hid a large part of that ship behind the smoke. He only saw the USS Kearsarge after he finished this painting and in another painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, entitled The Kearsarge at Boulogne, he depicted this ship. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas.

Where? Gallery 299 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

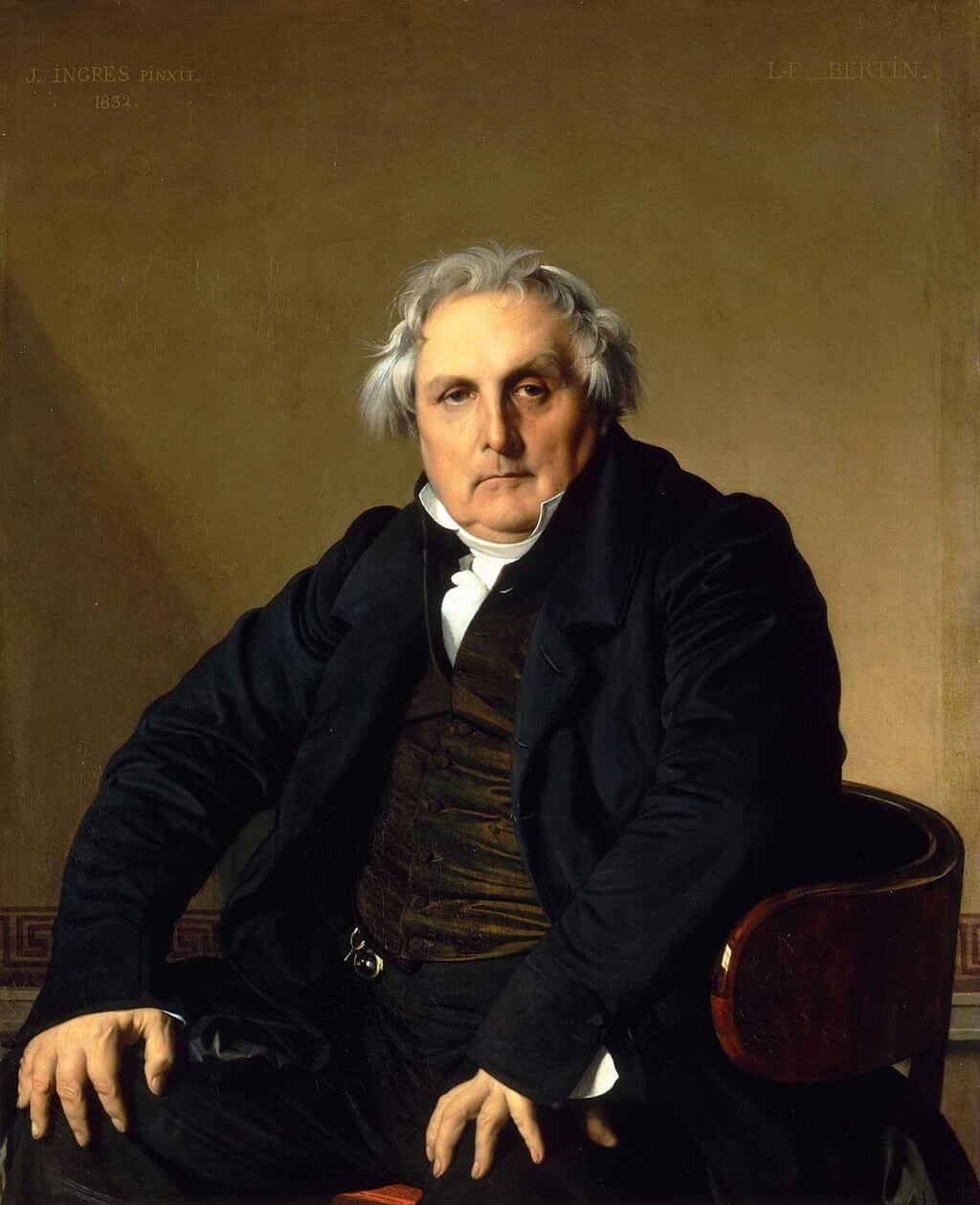

When? 1812 Commissioned by? Count Camille de Tournon, the son of the Countess de Tournon What do you see? A portrait of the about 60-year old Countess of Tournon sitting in an armchair against a brownish background. This painting often leads to some discomfort among the viewers. Unlike most other portraits by Ingres, the countess is not a young and beautiful woman. Most people agree that she is not very attractive. Ingres has depicted her quite realistically. For example, her eyes are a bit swollen, she has a very large nose, she has a faint mustache, and she has a bit of a double chin. She also has a wart in between her eyes. However, Ingres has probably also idealized some other parts as the Countess does not look like 60 years old. For example, look at her unwrinkled face and her smooth arms. Instead of her beauty, the painter has focused on depicting her alertness, wisdom, and confidence. She has a small, but confident, smile and looks directly at the viewer. She is dressed in expensive and fashionable clothes. She wears a white transparent veil with flower decorations in her hair, a lace ruff around her neck with a transparent undergarment of lace below it, and a green velvet dress. Over the armchair and on her lap lays a cashmere shawl with flower patterns. Backstory: This painting is also referred to in French as Comtesse de Tournon. Ingres created this painting while he was staying in Rome, which was at that time part of the French empire of Napoleon. The Countess of Tournon was born as Geneviève de Seytres Caumont and is the mother of Philippe-Marcellin Camille de Tournon-Simiane. Between 1809 and 1814, Camille de Tournon was the French Prefect of Rome during Napoleon’s reign. During a cleaning of the painting in 1995 by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the wart was discovered in between the eyes of the Countess. As the painting stayed for a long time in possession of the Tournon family, it is likely that a family member has applied some extra paint to this work after it was finished to conceal the wart. Who is Ingres? Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was born in 1780 in Montauban in the South of France and died in 1864 in Paris. His father was an artist himself, and from an early age, he provided Ingres with very good art education. In 1797, he became a pupil of Jacques-Louis David, who trained him as a Neoclassical painter. During his life, Ingres lived in Paris, Rome, and Florence. He wanted to become a history painter as that was considered to be the highest level of painting. However, in the early part of his career, he received relatively few commissions for history paintings. Instead, to support his family he created portrait paintings on commission. Portraits by Ingres: Ingres considered himself to be a history painter, but we remember him nowadays mainly because of his beautiful portraits. He has painted a large number of portraits during his career. For example, the two paintings of Madame Moitessier are well-known. The first version hangs in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the second version in the National Gallery in London. Two other examples of excellent portraits are Princesse de Broglie in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Portrait of Monsieur Bertin in the Louvre.

Fun fact: When a portrait of someone was commissioned, painters usually did their best to depict the person in a beautiful and flattering way. This is also what Ingres usually did as is evidenced by the portraits shown above. However, the Countess of Tournon is not primarily depicted as a beautiful woman.

The realism that Ingres included in this painting is comparable with some of the portraits of the 18th and 19th century Spanish artist Francisco Goya. A good example is the face of King Ferdinand VII of Spain in a portrait that Goya painted of him. Another example is the faces of Charles IV and his family in a painting by Goya in the Prado Museum. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas

Where? Gallery 258 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

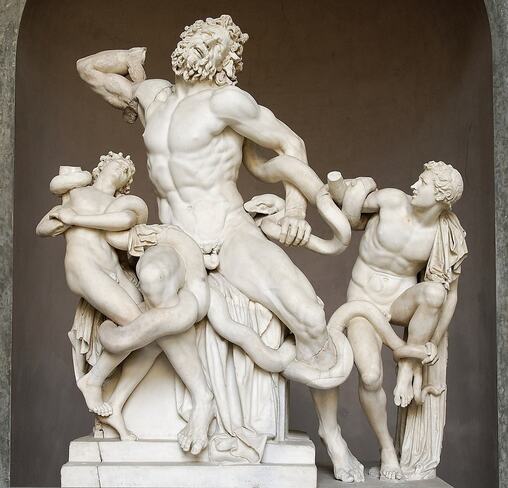

When? Between 1611 and 1618 What do you see? A muscular Prometheus is laying on the rocks. His left hand is chained to a rock. He has a white and blue cloth underneath him that barely cover him. Prometheus is depicted in the light, and there is a strong color contrast between him and the dark colors around him. In particular, the eagle is painted fairly dark and represents the evil force that he has attracted by stealing fire from the Greek gods and giving it to the humans. Prometheus looks at the eagle, who has his wings spread out and it looks like the eagle makes Prometheus almost fall of the rocks (though he is kept in place by the chains). The large beak of the eagle rips open the skin of Prometheus and takes the liver out of his body. The claws of the eagle are placed on his face and near his groin to emphasize the pain that Prometheus suffers. The pain is emphasized by the expression of agony on his face, the clenched fist of his left hand and the curled toes. These features draw similarities to the statue of Laocoön and His Sons in the Vatican Museums. On the bottom left you can see a small fire burning, which refers to the fire that Prometheus has given to the humans.

Backstory: This painting is based on the mythological story of Prometheus. According to the myths, Prometheus created a clay figure of a human and went on to steal fire from Mount Olympus. He gave the fire to the humans. Prometheus is being punished for stealing the fire from the gods. As a punishment, Zeus chained him to a rock on Mount Caucasus and made sure that and eagle would eat his liver. As Prometheus is immortal, his liver would grow back every day, and the eagle would come every day to eat it again.

The eagle in this painting is painted by Frans Snyders, who was a specialist in depicting animals. Rubens liked this painting because of the strong emotional response it triggered among viewers. Therefore, he decided to keep this painting for himself for a long time. Who is Prometheus? In Greek mythology, Prometheus is a Titan (an immortal Greek deity with incredible strength). He is the creator of the humans and has given fire to the humans by stealing it from Zeus on the Mount Olympus. Zeus hid the fire for humans, and after discovering that Prometheus had stolen the fire, he decided to punish Prometheus as depicted in this painting. The eagle was the symbol of Zeus himself. Prometheus suffered this punishment for hundreds of years until Hercules killed the eagle and freed Prometheus. Other Paintings on this Topic: The story of Prometheus has inspired many artists over the centuries. In particular, due to the painting of Rubens, several artists have created their artworks on Prometheus.

Who is Rubens? Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) was born in Siegen, in Germany. In 1589, he moved back with his mother to Antwerp, where his family originally came from. Between 1600 and 1608, Rubens traveled through Italy and got inspired by the Italian artists. He started his trip in Venice where he was particularly impressed by the works of Titian. He learned from Titian’s work how to use colors to express emotions in his paintings.

Rubens also traveled to Florence and Rome where he got inspired by the works of Michelangelo. He learned from Michelangelo’s work how to design a painting and how to design the human figures in a painting. In Italy, Rubens also became familiar with the works of Caravaggio from who he learned how to effectively use the contrast between light and dark in a painting. In 1608, he returned to his native Antwerp. He was appointed as court painter of the Low Countries, and he set up a large studio in Antwerp. Who is Snyders? Frans Snyders (or Snijders) was born in 1579 in Antwerp and also died there in 1657. He was an expert in painting animals, hunting scenes, and still lifes. An example of the animals that he painted can be seen in the Wild Boar Hunt. Snyders often collaborated with painters such as Jordaens, Rubens, and Van Dyck. He assisted particularly often in the works of Rubens, usually by including fruit or animals in the paintings. Sometimes, Rubens would create the rest of the painting first and sketched the area where Snyders’ should contribute his part. However, for this painting, Snyders started by painting the eagle and Rubens completed the painting.

Fun fact: The Philadelphia Museum of Art commissioned Locust Moon Press in 2015 to create a comic book based on this painting by Rubens. The idea was that Prometheus could be seen as a superhero and a comic book would appeal to the younger generation. Ten great comic book artists created their versions of the Prometheus painting through illustrations. The result is not so much appealing to children, but to a wide audience. More information on the comic book can be found here.

Where? Gallery 161 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

When? 1899 What do you see? A pond full of water lilies. The green leaves of the water lilies are resting on top of the water and are scattered across the pond. Many of the water lilies are blooming, and the large flowers stick out of the water. They are predominantly white, but Monet adds some hints of other colors, like blue, pink, red, and yellow, to depict the flowers. The pink and red tones are more visible in the water lilies in the back. Foliage surrounds the pond. A blue Japanese-style wooden footbridge crosses over the pond. In the background, a dense collection of trees covers the sky. On the left, you can see the hanging leaves of the willows. You can see the reflection of the water lilies, the plants, and the trees in the pond, but at places, you can also see the transparency of the water in the pond. Monet must have had several people that kept its pond very clean to be able to see all these reflections in the water. Backstory: In 1883, Monet moved to Giverny, about 45 miles Northwest of Paris. In 1893, he got the idea to buy a piece of land with a small pond next to his property. He expanded this pond and turned the land into a Japanese water garden full of bushes, flowers, trees, and water lilies. He also added a Japanese-style wooden bridge which you can see in this painting. Several years later, Monet started to paint the pond with the water lilies and the bridge and continued to do so for the last 27 years of his life. Monet chose to omit the sky and the edge of the water in the foreground to try to fully absorb the viewer in the view of the water lily pond.

The Water Lily Garden: Giverny Monet’s Garden is open to the public, and about 500,000 people visit the garden every year. It consists of the house of Monet and two parts of the garden. The first part is the flower garden which is full of common and rare varieties. Monet developed a love for gardening and was always on the lookout for rare flower species.

The second part of the garden is the Japanese-inspired water garden that you can see in this painting. His design of the water garden was inspired by prints of gardens in Japan that he collected (though Monet had never visited Japan). Monet was so inspired by this garden that he created about 250 paintings of it (though not all of them have survived as Monet destroyed some of them and others have been affected by fire). He painted the water lilies at different times of the day and at different times during the year, such that every painting looks a little bit different. For example, the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibits the Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies, and the National Gallery of Art shows The Japanese Footbridge. Other examples can be found in, amongst others, the National Gallery, the Musée d’Orsay, and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

Who is Monet? Oscar-Claude Monet (1840-1926) was born in Paris. He is considered to be one of the founders of impressionism. Together with artists like Cézanne, Degas, Pissarro, and Renoir, Monet set up several exhibitions in Paris in 1860 and 1870 to expose the public to this new style, including the painting Woman with a Parasol - Madame Monet and Her Son, which is now in the National Gallery of Art.

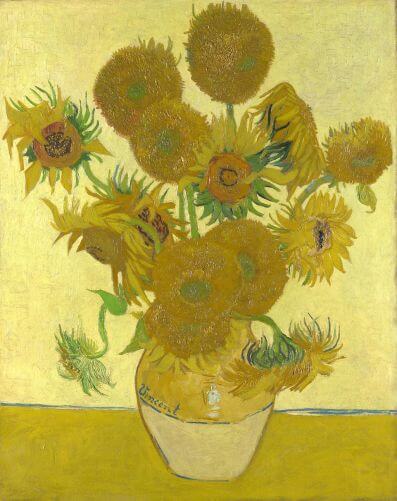

Monet was a very productive painter and his work has a unique style and subjects. For example, where many people associate sunflowers immediately with Van Gogh, water lilies are associated with Monet. Monet created gardens at all places where he lived, but the water lily pond was by far his favorite garden. He also traveled a lot through Europe to find nice landscapes which he used as an inspiration for his gardens and paintings.

Fun fact: Monet wanted to have exotic plants and water lilies in his garden, but the local community was against it as they were concerned that these exotic flowers would poison the water in Giverny. However, Monet proceeded anyway and imported flowers with the most beautiful colors from around the world. His water lilies came from Egypt and South America.

In 1912, Monet got diagnosed with cataracts in both eyes and his sight suffered because of that. He could not perceive colors in the same way anymore and that was reflected in his paintings. For example, instead of using predominantly blue, green, and white for the water lilies, he started to use more yellow and purple. As a result of this, Monet decided to paint more abstract paintings beginning in 1915.

Where? First floor, room 700 of the Denon wing in the Louvre. A smaller version is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art but is currently not on display.

When? The original is from 1827, and the smaller replica is from 1844. What do you see? In the center, King Sardanapalus of Assyria, dressed in white, lays in his bed which is covered with bright red sheets. On the front corners of his bed are two large elephant heads. His bed stands on top of a large pyre. You can see some woodblocks making up the pyre behind the black slave in the left foreground and on the bottom right. While rebellion forces surround his palace, Sardanapalus orders his eunuchs and palace officers to cut the throats of his mistresses. He did not want anyone or anything that gave him pleasure during his life to survive him. He has a calm and disinterested expression which contrast strongly with the cruel scene around him. Notice also that all mistresses and Sardanapalus wear expensive jewelry as the king also wanted his royal possessions to be burned with him on the pyre. On the bottom right is also a collection of crowns and jewelry that are about to go down.

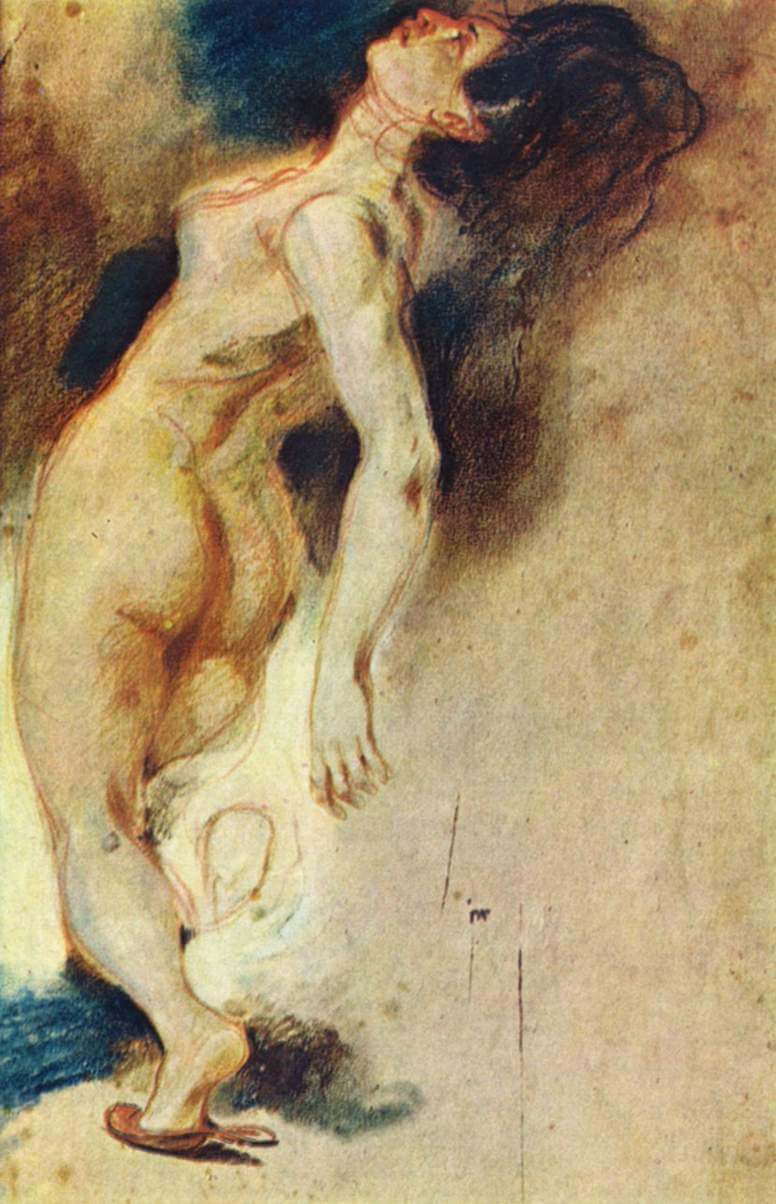

Backstory: Delacroix got his inspiration for the theme of this painting from a play written by the English poet Lord Byron, who in turn was inspired by older texts on the story of Sardanapalus. In 1821, Lord Byron wrote a play called Sardanapalus: A Tragedy (Amazon link to this book) which describes the crazy story of the death of Sardanapalus. In preparation for this painting, Delacroix also consulted some older writings on the death of Sardanapalus. He combined all these sources to create a unique story on the death of Sardanapalus. We can still identify some figures in this painting based on Lord Byron’s play. For example, the man on the left removing a spear from his chest is Salemenes, the brother-in-law of Sardanapalus. He just came back from the battlefield and will die after he removes the spear. And the woman lying on the bed is Myrrha, the lover of Sardanapalus. According to Lord Byron’s story, she was the only one with Sardanapalus on top of the pyre. Who is Sardanapalus? According to the Greek writer Ctesias, Sardanapalus lived in the 7th century BC. He was the last king of Assyria, which was a very large empire in the Middle East between the 25th and 7th century BC. He lived an extremely luxurious life and was very lazy. According to Sardanapalus, the main purpose of life was physical desire. He followed his own advice, dressed in woman’s clothes, wore makeup, and was surrounded by many male and female mistresses. As many people got annoyed by his lifestyle, a group of rebellions formed to defeat Sardanapalus and his troops. Sardanapalus went down in a typical fashion. As some point during the war with the rebellions, he thought that he had defeated the rebellions and started a big party. However, the rebellions came with reinforcements and defeated Sardanapalus, leading to the end of the Assyrian empire. Before he got caught, Sardanapalus burned himself together with many of his eunuchs and mistresses, and most of his royal possessions. Who is Delacroix? Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) was the leader of the Romantic painters in France. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was the main artistic rival during his life. Whereas Ingres was the leader of the school of Neoclassical painting, Delacroix believed in the Romantic style and was inspired by artists like Rubens, Tintoretto, and Veronese. The style of Delacroix can be characterized by an emphasis on using colors and depicting emotions, and not on providing a clear composition and shapes of the people in his paintings. In 1830, he painted his most famous work, Liberty Leading the People, which is on display in the Louvre as well. The work of Delacroix has been important for the development of Impressionism later in the 18th century. Artists like Degas, Manet, and Renoir greatly admired the work of Delacroix.

Fun fact: This painting is the largest uncommissioned by Delacroix. He had high hopes of this work and created many sketches that are still available for this painting. Below are two pictures of sketches he made that are in possession of the Louvre.

The painting was first exhibited in the Salon of 1828 in Paris. The painting got many negative reviews. One viewer went so far as threatening to cut off Delacroix's hands such that he could never paint again. There were several reasons for these negative reactions, such as the messy composition and incoherent use of colors. Whereas the French State bought earlier paintings of Delacroix, they did not buy this one. Instead, Delacroix took it back to his studio where it stayed until 1845. He only sold the painting after he made a much smaller replica of the painting owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The larger painting was not on public display until 1921 when the Louvre bought it. Nowadays, this painting is highly appreciated. Looking back, it is one of the early Romantic paintings. Whereas people in the early 19th century were still used to the clarity of the Neoclassical paintings by Ingres and colleagues, the Romantic paintings focused on showing emotions in a more chaotic setting. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us