|

Where? The Octagonal Court of the Museo Pio Clementino in the Vatican Museums

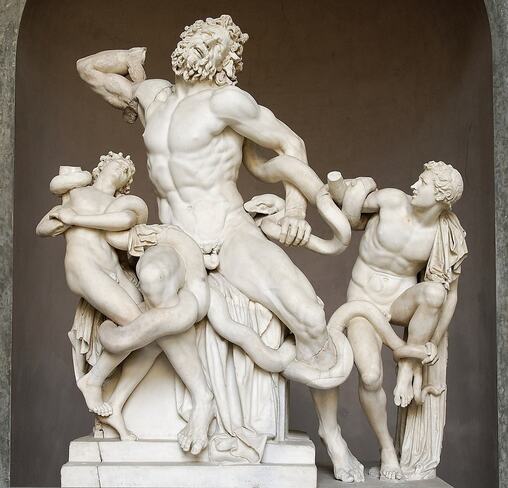

When? Uncertain, but estimates range from the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD. By who? Unclear, but probably this is a Roman copy of an ancient Greek original in bronze. Some people suggest that it was made by the three Greek sculptors Hagesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus. What do you see? This life-size statue is made of seven different blocks of marble and shows Laocoön and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, being attacked by two sea serpents. Laocoön sits on an altar and is sculpted as a very muscular man. He strains every muscle that he has to escape from the serpents. The oldest son on the right seems to break free from the serpents and looks at his brother and father. Laocoön and the youngest son on the left are in big trouble, and their faces express their struggle. The youngest son seems to cast a last glance at his father, but he looks to be (almost) dead already. Notice that the serpents are trying to kill Laocoön and his sons both by constricting and biting them. You can see the head of one of the serpents next to the left hand of Laocoön. You can also see that a few pieces are missing from this sculpture.

Who is Laocoön? According to Greek mythology, Laocoön was a Trojan priest. There are various accounts of his story. Virgil describes the most popular version in the second book of the Aeneid. According to him, when the Greeks left Troy, they left as a gift a very large wooden horse in front of the gates of Troy. Laocoön suspected that this horse was a trick of the Greeks and tried to convince the people of Troy not to accept the gift.

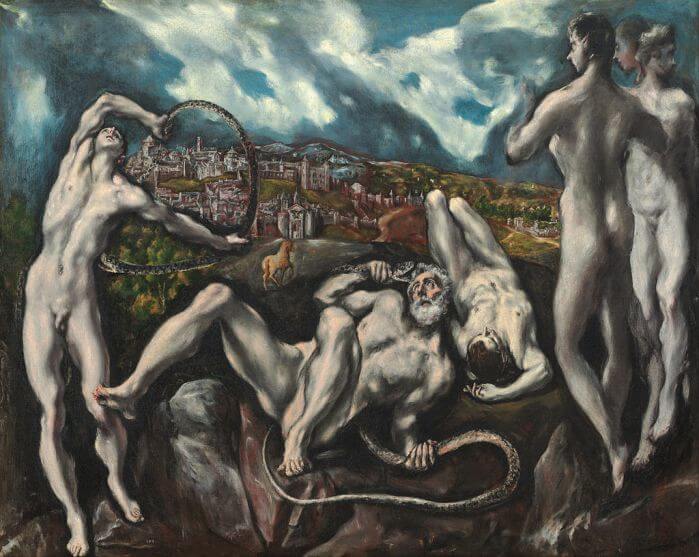

To prove that the horse was a trick, Laocoön struck the horse with his spear to show that it was hollow. Poseidon and Athena then punished him for his interference and Laocoön and his two sons were attacked and killed by two sea serpents named Porces and Chariboea. The Trojans interpreted this event as a sign that the horse was not a trick and they took the horse into their city walls after which the Greek came out of the horse during the night and defeated the Trojans. Copies: Many copies of this statue have been made and can be found across the world. A well-known copy is the marble version by Baccio Bandinelli in the Uffizi Museum in Florence. Another bronze version made by Francesco Primaticcio for King François I of France is in the Louvre. Jean Baptiste Tuby made a copy for the Park of the Château de Versailles in France. The Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia, has a terracotta version of this sculpture by Stefano Maderno. Some other places that have a copy of this statue are the Mannheim Palace in Germany, the Archeological Museum of Odessa in Ukraine, Houghton Hall in England, and the Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes in Greece. This statue has also inspired many other artists to depict the story of Laocoön. For example, El Greco created a painting of Laocoön that is now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Several parodies of this sculpture have also been made over time. For example, Niccolò Boldrini made a woodcut around 1540 for which he copied a drawing of Titian in which monkeys replace Laocoön and his sons.

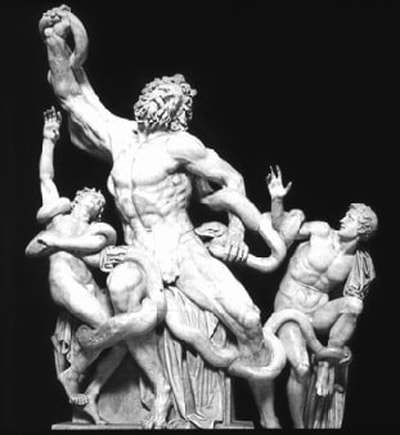

Fun fact: The statue misses a few limbs and parts of the serpents. Over time, the missing parts were added to the sculpture and sculptors, including Antonio Canova did various restorations. The right arm of Laocoön was already added in the 16th century, but there was quite some discussion on whether the arm would be straight up or bent back over the shoulder (which Michelangelo suggested). The experts chose that the arm would be straight up and you can see in the picture how the statue looked before 1960.

In 1906, an archeologist found a right arm of a sculpture which he thought could be the missing right arm of the Laocoön sculpture. He donated the arm to the Vatican Museums, but only 54 years later the museum verified that it was indeed the missing arm of Laocoön, and it was added to the sculpture. The missing right arm was bent over the shoulder as Michelangelo supposed (this also means that the replicas of this sculpture from before 1960 are incorrect). In the 1980s all non-original additions to the sculpture were removed, and the sculpture became like we can see it today.

Written by Eelco Kappe

References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us