|

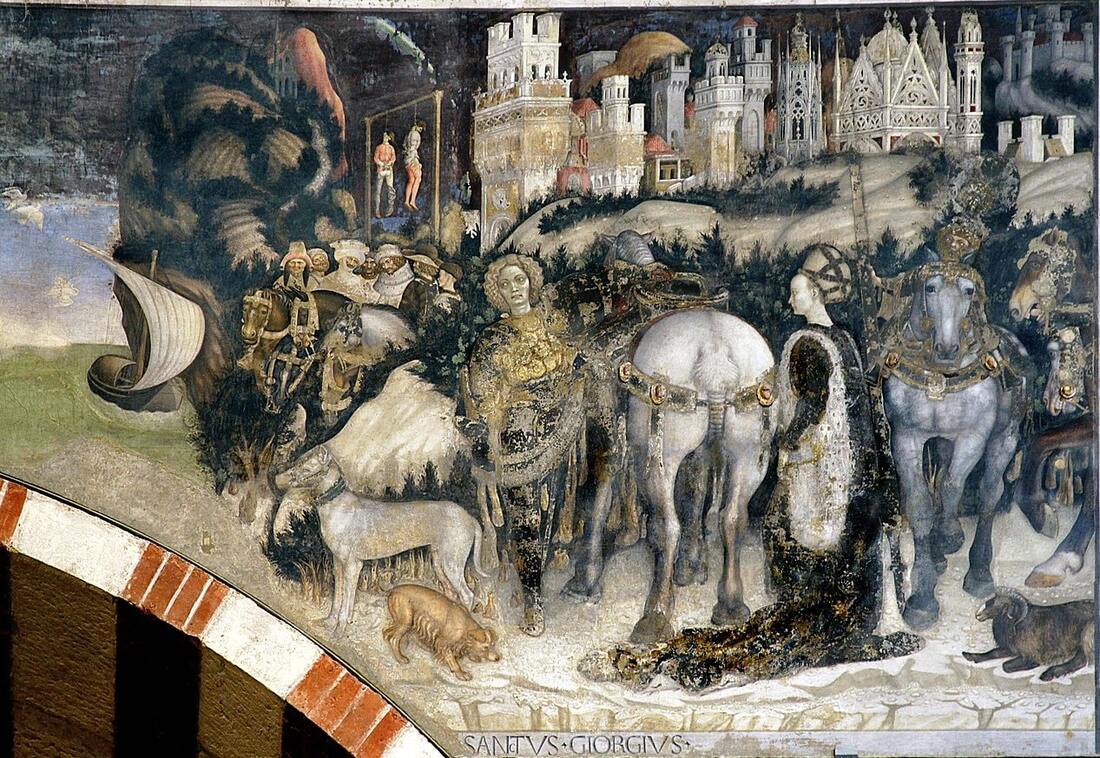

Where? Pellegrini Chapel of the Church of Sant’Anastasia in Verona

When? Probably 1435-1438, but some scholars say the completion date was between 1444 and 1446 Commissioned by? The Pellegrini family General Information: This fresco, based on “The Golden Legend”, was painted above the arch, outside the Pellegrini’s funerary chapel in the crown and spandrils of the architecture, to the right of the sanctuary. It was executed, only partly, in true fresco on wet plaster, then elaborated a secco when the plaster dried. Because of these techniques, much of the fine detail and ornaments have scaled off. It has also been exposed to water from ceiling seepages and been severely damaged by this, especially on the left side which contained the dragon. Both sides of the fresco were removed for restoration, the left side in 1891, and the right in 1900. This caused the loss of the metallic and gilt decorations. Pisanello’s fresco was part of a cycle decorating the whole chapel. The Golden Legend: It tells the tale of St. George and the Dragon. There are many versions. The St. George whom the Pellegrini family selected for its burial chapel, was a soldier who proclaimed the Christian faith, banned under Roman emperor Diocletian and was put to death as a consequence, around 303 AD. The list of his miraculous deeds and the persecutions he suffered has grown longer each century. He became a much-revered patron saint of cities and associations. The version pertinent to this fresco was part of a series compiled by Jacopo de Voragine in the 13th century. The story finds George, a native of Cappadocia, on the road to the city of Silena in the province of Lybia. Silena had been terrorized by a plague-bearing dragon. It lived in a lake and would come to the city walls and poison all who came within reach of its breath. The citizens of Silena appeased the Dragon by feeding it two sheep a day. When these became scarce, they fed it a single sheep and a single human, chosen by lot. Eventually, the lot fell to the King’s daughter and with much sorrow, he resigned himself to her sacrifice. He sent her down to the lake dressed in regal garments and, there, she happened upon St. George. The princess told St. George to flee, but instead, the saint mounted his horse, armed himself with the sign of the cross, went across the lake, and pierced the dragon with his lance. The princess put her girdle around the dragon’s neck and led it to the city, where, after the citizens agreed to be baptized, St. George slew the dragon with his sword. What do you see? The painting follows the legend faithfully. Most artists who painted this tale chose to show St. George vanquishing the dragon. Pisanello chose to depict the moments beforehand. The right side of the fresco: To the right of the white horse in the center is Princess Silena dressed in luxurious garments made of fine fabrics and fur. Her large mass of hair is held in bands of braids and begins very highly on her brow, according to the early 15th century style. Lit candles were used to ensure the correct trim at her forehead and temples.

Resting on the ground to the right and behind her is the sacrificial “sheep”, in the form of a ram. Just behind her is St. George’s squire, carrying St. George’s helmet and the lance that will pierce the dragon. He is a dwarf and was probably a member of the Gonzaga household in Mantua, as he is seen in Pisanello’s Arthurian fresco that was painted there. His horses’ harnesses and the squire’s armor were, originally, decorated with silver and gold, as was popular in chivalric art. The eyes of the squire’s horse are set forward with the effect of engaging the immediate attention of the viewer. Two more horse heads are visible at the right edge with their feet in motion and ready for action. Note the foreshortening of the two horses, one seen from behind and one from the front. This was a new perspectival technique that Pisanello employed.

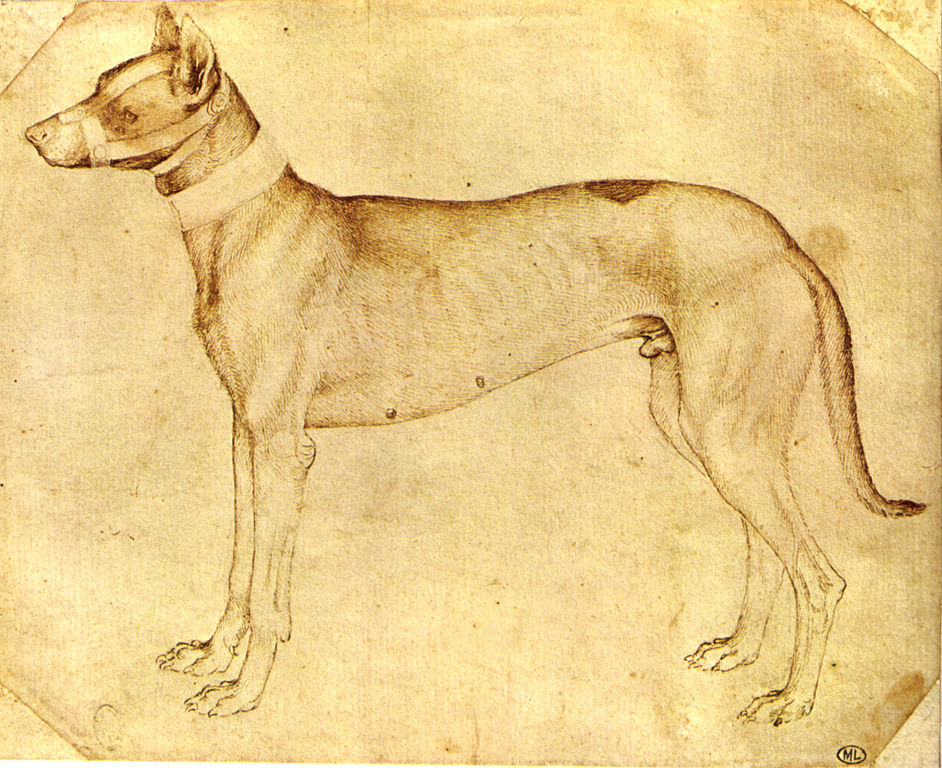

St. George is clearly defined by his fine clothing and his curly golden locks. He stands to the left of his horse, near the edge of the lake. He has his left foot in the stirrup, ready to mount and ride off in pursuit of the dragon which lurks on the other side of the water. He looks towards the dragon’s lair with eyes wide with fear and anticipation. Next to him are a hound and a companion dog. To the left and further back is a sailboat, ready to transport St. George across the lake to the dragon.

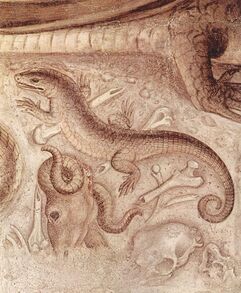

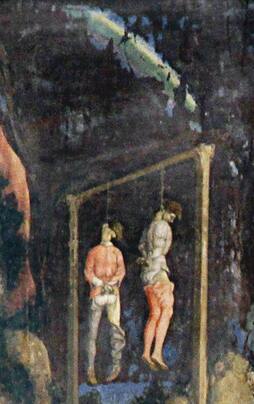

Background of the right side of the fresco: To the back and left of St. George is a group of seven men tucked behind three elaborately decorated horses. They stand near the point of embarkation for the sailboat. On the far left is a foreigner, his twirling moustache, muscular, broad face and narrow eyes indicate a Mongol. His features contain a suggestion of menace. Beside him, a man is turning his head in fear whether because of his frightening neighbor or the dragon is not clear. The elaborate headdress on the Asian man in the middle is seen in many of Pisanello’s drawings, suggesting that these visitors were fairly common to the area at the time. The knight with the ermine hat and collar, bowing his head so hopelessly, is probably the princess’s father. Directly behind that is a gibbet with two hanging men, who are depicted in great detail as if the viewer were standing beneath the gallows. Over the gallows is a rainbow painted right down to the ground. This is a reference to St. George and symbolizes the divine protection of God. To the left of the hanged men is a dark, foreboding rock that goes to the sea. There is a tower at the top of the rock painted grey and barely distinguishable. The whole scene is atmospheric with foreboding and creates a deep tension. The towers of the city governed by the princess’s father rise on top of the hill in the background, some of them, adorned with Gothic open-stone ornament. On the far right stands a medieval fortress, the architecture still designed solely for defense. Pisanello made use of hierarchical perspective in the fresco. We see distance by position and size. Techniques for spatial distancing and the use of linear perspective in painting became common later in the 15th century. The left side of the fresco: Only few details have survived on this side. Sadly, the dragon in the sea has disappeared completely. The barely discernible scene of his lair, where the creature devoured his prey and offerings from the kingdom, reveals macabre human skulls and bones along with various animal remains. Small parts of an antelope, a deer and lion are visible. An excerpt from George Francis Hill’s book Pisanello fills in the blanks. “The main object apparent in the landscape----is the dragon, crouching toward the right with wings closed and tongue flickering out from between its two open jaws. Below it are apparently two of its brood, wingless; and clearly two human skulls and some bones.”

A comparison with Bono da Ferrara’s St. Jerome and other works, led Hill to the conclusion that this pilgrim, with some faults of “draughtsmanship”, was left by “the master” to be painted by Bono, who was probably in Pisanello’s workshop at the time. The imperfections include “short and feeble arms, hands that are nerveless and the foreshortening of the pilgrim’s right foot is not successful.”

Canting badge: A heraldic device that represents the bearer’s name in a visual pun or rebus. In this case, it shows the pilgrim as a representation of “Pellegrini” which means pilgrim in Italian. The ermine border of this badge ties itself to the man in the ermine hat in the painting and hence to the Pellegrini. It becomes more than just a simple identifying device. The family is then associated with the act of pilgrimage through the represented pilgrim, a message as well as the pun.

The seashell on the pilgrim’s hat is a symbol or proof of pilgrimage or baptism. Baptism is the start of the Christian journey. His presence here becomes appropriate then with the commissioning family and the religious overtones. The Pellegrini were baptized, were Christians, and had made the journey. The prominence of the prayer beads in his hands reinforces his piety but also the fact that the Dominicans were promoting the use of these beads for Catholics in the 15th century.

Backstory: This fresco is also known as St. George and the Princess of Trebizond. There is nothing in the literature to explain why this fresco has two titles. Trebizond is on the Black Sea and is called Trabzon today. It is a provincial capital in northeastern Turkey. Silena lies in the vicinity of modern-day Beirut close to 900 miles away. Commentators debate the city used. Pisanello was in his late thirties to mid-forties when he painted it. His reputation as one of the most sought-after painters of the day was firmly established. He had spent most of his early artistic life in Northern Italy in the service of warring condottiere and the petty rulers of the various principalities and city states. His art must be seen against the background of Italian battles for territories, shifting alliances amidst the decline of the Byzantine empire, and the fear and uncertainty due to the loss of the empire’s protection of Italian trade routes. The rise of Islamic power was also a major threat. This explains the foreigners with the princesses’ father who do appear to menace, as they menaced Italian trade routes in the 14th and 15th centuries in Europe. Nor can this work be understood without an explanation of the remaining influence of the chivalric code. The crusades were in the distant past but chivalric code still defined the medieval knight system: the paramount importance of religion, the moral and social code of courtesy, the need for generosity, martial valor, and dexterity in arms, supposedly leading to gallant deeds, devotion and loyalty. This has been romanticized in literature, music, legend and art. This social code remained influential to the aristocracy in the first half of the 15th century. Pisanello was a man of this time. He had one foot in late International Gothic Art – with intense attention to reality and detail – yet his interest in fanciful, imaginary tales and his representation of them remained in Medieval Art. He had kept his association with Verona all his life so it was natural that the Pellegrini family would commission Verona’s most celebrated painter, Pisanello, for their funerary chapel. Pisanello is documented as living in Verona in 1433 with his widowed 70 year old mother, 4 year old daughter, Camilla and 2 servants. It is not known when he started or how long it took to paint the frescoes. His detailed hatching technique would have been extremely time consuming, as would the application of the silvering, gilding, and pastiglio in details like the horse’s harnesses. (pastiglio is the paste work or low relief decoration normally modelled in gesso on white lead, applied to build up a surface that may then be gilded or painted or left as it is.) There are very few of his paintings left. However, there are hundreds of drawings. These have been gathered together in The Vallardi Codex in the Louvre. Most are by Pisanello, but also many by his pupils and other artists, including drawing of horses, dogs, wild animals, costumes, heads of Mongols and Tartars, plants, men dangling on the gallows. In much the same way as he built his fresco on the wall, once he completed the composition, he could go to his store of drawings and fill in the necessary details from his patterns.

The architectural structure of the chapel would have been a consideration in his composition and perhaps even determined the precise scene he chose. Pisanello presents us with the novel setting. The viewer is presented not with the event itself, but with imminent action, filled with fear, anticipation, horror of what lies ahead. We see the stoic princess, the fearful father, the brave knight, his squire ready and waiting, and the macabre criminals hanging. On the other side the dragon rages, snorting out smoke and fire, the animal and human remains, the live animals awaiting their fate, unknowing. Who will win…Good or Evil? All viewers would have known the outcome.

The Gibbet: The gibbet with two men hanging has been interpreted in several ways. This may be a touch of realism, since it was customary for hangings to take place outside the city walls. However, they have also been said to be a reminder of man’s mortality, appropriate in a scene which is concerned with Christian conversion. The presence of the rainbow may signal the possibility of redemption, also an appropriate message for the scene. There are also those who suggest political overtones for Verona are implicated in the tale.

However, on further reading of the translation of St. George, Martyr: (Jacobus Voragine: 1275: Beaten and Imprisoned): “he did do raise him on a gibbet; and so much beat him with great staves and broches of iron, that his body was all tobroken in pieces. And after he did do take brands of iron and join them to his sides, and his bowels which then appeared he did do frot with salt, and so sent him into prison. But our Lord appeared to him the of same night with great light and comforted him much sweetly. And by this great consolation he took to him so good heart that he doubted no torment that they might make him suffer.”

St. Georges end, according to the legend, was not pleasant but the clear message was that God will always protect those who believe in him. The rainbow behind the gibbet, descending to the ground, along with the other features in the painting suggest the more religious orientation of protection and redemption for Christians. Pellegrini Family: The chapel in the Dominican Church of Sant’Anastasia belonged to the Pellegrini clan of merchants who had grown wealthy over several generations. They made their money from the cloth trade. They numbered amongst the most respected families in Verona and were among the highest tax-payers. One of the ways a family could both publicize its status and document a long line of succession was a burial chapel. Their chapel was in the most prominent location in the church, near the choir, which further enhanced their position in society. The Pellegrini had a collection of suits of armor, and they chose the traditional representation of the cult of chivalry for the entrance of this burial chamber. What better way to honor their religion, their family, and their social status than to have Pisanello paint a tale with the lady in distress, a knight in shining armor, the eventual triumph of good over evil, and the baptism and salvation of all concerned? Pisanello painted a world that was perhaps already in decline, but, today, it is a window for the viewer to examine a distant part of European culture. Who was Pisanello? His exact date of birth is unknown but sometime near 1394 is the best estimate. His father, Puccino di Giovanni di Cereto, was a wealthy cloth merchant and his mother, Isabetta, was a native of Verona. Pisanello is mentioned in his father’s will in 1394. It is believed that following his father’s death, he and his mother moved to Verona and he grew up there. He bought a house in Verona in 1422 and always regarded himself as a Veronese citizen. The first two decades of his life are obscure, although in 1416 he was referred to as “magister” (master) and by 1424, he was called “pictor egregious” (distinguished painter). A 1425 Gonzaga account book (Mantua) referred to him as “Magester Pisanellus Pictor”. These titles ensure us that his career as an artist was recognized. Between 1415 and 1419 he was in Venice working and studying as a pupil or colleague of Gentile Da Fabriano (1370-1427), a International Gothic painter. Pisanello learned much from him and his influence is visible in his paintings. The two of them worked together on the frescoes in the Doge’s Palace in Venice (which were overpainted in 1479). Pisanello was in Rome in 1431-1432 completing the fresco cycle of The Life of John the Baptist (destroyed in 1646 during a remodeling of the church) that Da Fabriano had left unfinished because of his death. Pisanello succeeded Da Fabriano as the major Italian exponent of the International Gothic style. While he was in Rome, he must have been accepted into the Papal household as Eugenius called him “beloved son”. The earliest of all records are from Mantua where he lived and worked for Gianfrancesco Gonzaga and later his son, Lodovico Gonzaga. The family ruled Mantua, and Pisanello worked for them from 1422 to 1447. The patronage of these ruling families provided a livelihood for artists, and their recommendations to others provided further commissions. Pisanello managed to keep a balance and was employed by many of these petty rulers throughout his career. In the late 1420s, Pisanello was in Milan working for Filippo Maria Visconti, duke of Milan. In 1426, he made a painting for the Brenzoni Monument in the Church of San Fermo, Verona. This beautifully executed work with the delicacy, illumination, composition, and careful detail to expression, costume, and colors is a testament to his great talent. Close view shows even the eye lashes, painted to perfection by the artist in this delicate rendering of the Annunciation.

He became court artist to Alfonso V of Aragon, King of Naples in 1448-9 with a large stipend of 400 ducats a year. He died probably in Rome between July and October of 1455.

He is most known for his delicate, precise, and beautiful drawings, and for the cast bronze medals he popularized. These were roundel sized and meant to be passed from hand to hand, each bearing personal portrait studies from life. Little is known about his personality, but from his arrest and trial, it appears he had some political passion as well as his prodigious talent.

Fun Fact: Members of the family were buried in the Pellegrini Chapel from 1387. From, Negotiating the Gift: Pre-modern Figuration and Exchange (p. 211): “Investment in church art and investment in mass-sayings were understood to be strongly equivalent to the extent that one could be exchanged for the other. In his last will of 1429, Andrea Pellegrini ordered that his body be buried in his family chapel in the Church of Sant’Anastasia in Verona and that for three years continuously, the mass of St. Gregory shall be said for his soul. He also stipulated that a terracotta statue of him kneeling and saying prayers be completed and placed in the chapel within three years of his death. Why stipulate the same number of years for the saying of masses and for making of the sculpture? When the saying of the masses ceased, the sculpture would be in place. The implication is that the praying effigy would take over the work of the prayers. In this case, Pellegrini was right to assume that the effigy would outlast the workings of the church ritual: the terracotta figure is still there, directly praying towards the altar in the chapel.”

Pisanello’s frescos are linked to the Pellegrini family through the same will. Andrea Pellegrini left the enormous sum of 900 florins for the project. The details from the will, along with the many Christian messages in the fresco make it clear that the Pellegrini were strong in their Christian beliefs and that they sought salvation in life and death. Pisanello was able to represent their desires through his art.

8 Comments

|

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us