|

Where? Second floor, room 846 of the Richelieu wing in the Louvre

When? Between 1626 and 1628 What do you see? A prostitute smiling provocatively. She has half of her breasts exposed. The use of light emphasizes her expression and cleavage. She wears a white linen garment with a salmon-colored bodice on top of it. She has rosy cheeks and looks to her left (our right). It seems that she is seducing a potential client. By 17th- and 21st-century standards, the woman may not be very pretty. She has a somewhat big nose, not a very smooth skin, and her hair is somewhat unkempt. However, her facial expression is so intriguing that this work leaves a lasting impression on those who view the painting. Frans Hals used loose and rough brush strokes for this painting. While Hals is known for his loose brush strokes, in this painting he used them more than in most of his other works. The style used for this work helps to make The Gypsy Girl very memorable. Backstory: Louis La Caze owned this painting in the 19th century. He was a doctor from Paris and an avid art collector. He gave the name The Gypsy Girl to this painting. This title is not very accurate as he did not recognize that Frans Hals actually painted a prostitute (though she may have been a gypsy). La Caze left this painting for the Louvre after his death in 1869, together with 568 other paintings. When the Louvre received the painting, the influential newspaper Gazette des Beaux-Arts praised Hals as the best painter ever. Malle Babbe: This painting is also sometimes referred to as Malle Babbe. However, this name is incorrect as Hals has another painting entitled Malle Babbe. This painting is in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. The confusion can be explained as a popular Dutch song, entitled Malle Babbe, was written in 1970. This song was inspired by the Gypsy Girl. However, the writer of the song, Lennaert Nijgh, mistakenly thought that The Gypsy Girl painting was called Malle Babbe.

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was born in 1582 or 1583 in Antwerp, Belgium, and died in 1666 in Haarlem, The Netherlands. When Hals painted The Gypsy Girl, he was inspired somewhat by the works of Caravaggio. However, Hals differed substantially from Caravaggio as he left out many (distracting) details in his paintings and focused on the composition and the expression of his subjects. This allowed Hals to give his subjects a personality.

While Hals was a popular local painter during his life, his works were largely forgotten after his death. The Impressionist painters rediscovered his work in the 1860s. Artists like Manet and Monet were inspired by the lack of detail, beautiful composition, and the loose brush strokes of Hals. The work of Hals has only gained in popularity since. Some beautiful works of Hals include his series on the four evangelists, of which Saint John the Evangelist is in the Getty Museum, and the Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Fun fact: Radiographic analysis of this painting revealed that Frans Hals initially wanted to paint a less provocative version of this woman. Her breasts were smaller and less exposed. However, Hals decided to make the painting more provocative. This painting shows more cleavage than any other painting by Hals. The open mouth of the woman is also a telltale sign. Decent women from the 17th century would never be depicted with a smile or open mouth in a portrait as that was considered indecent.

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster.

3 Comments

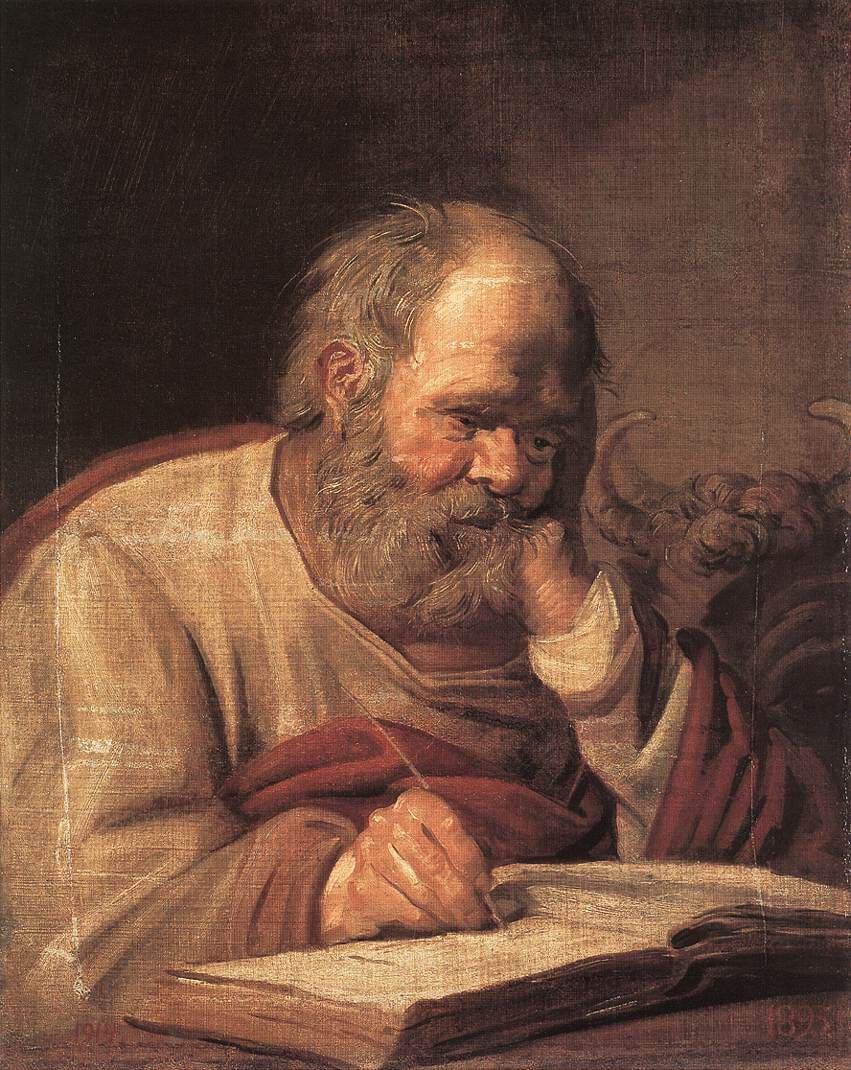

Where? Room E203 of the J. Paul Getty Museum

When? 1625 What do you see? A young Saint John the Evangelist sits in a room. He has red cheeks and wears a red/pink robe with a bold red cloak over his shoulders. He looks up into the light which represents the divine inspiration for the writing of a Biblical book. Saint John holds a quill pen (a pen made of a bird feather) in his right hand, and he has just dipped the pen in the pot with ink on the bottom left. He presses his left hand pressed to his heart to indicate his personal faith that helped him to write the Biblical book. On the right is an eagle which is one of the attributes of Saint John the Evangelist. Frans Hals used broad visible brush strokes to create this painting. His brush strokes are more refined in the face of John. He also makes brilliant use of the light to depict John the Evangelist. Backstory: This work is one of the few religious paintings by Frans Hals. About eighty percent of his works are individual portraits of upper-class people, wedding portraits, or group portraits. The remainder of his work consists mostly of genre paintings. The painting of Saint John the Evangelist is part of a series of four paintings of the apostles, with the other ones being St. Matthew, St. Mark, and St. Luke.

Who is Saint John the Evangelist? The author of the Gospel of John, the fourth book in the New Testament. Before becoming an Apostle of Jesus he was a fisherman. However, it is not certain if the Apostle John is also the author of the Gospel of John, as the author does not clearly identify himself in his writings. He is the only apostle that was not killed because of his faith in Jesus. Some people also attribute the Book of Revelation to him, though this is also a point of debate among scholars.

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was born by the end of 1582 (or early 1583) in Antwerp, Belgium, and died in 1666 in Haarlem, The Netherlands. His brother and five of his sons were also painters. Frans Hals is primarily known for his portraits. He had a loose painting style, which means that he used relatively few (but long) brush strokes to depict something. You can often see the brush strokes in his paintings. He painted based on his intuition and was uniquely able to capture the emotions and characteristics of the people he painted. Together with Rembrandt and Johannes Vermeer, Frans Hals is generally considered the best Dutch painter of his time. While living around the same time, the three of them all had unique styles and never met each other in person. Another interesting painting of Hals is the Portrait of René Descartes, the father of modern Western philosophy. This painting is in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen. There are several copies of this painting among which one is in the Louvre in Paris.

Fun fact: This work is part of a series of four paintings in which Frans Hals depicted each of the four evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. All four paintings were lost since 1812 and were only rediscovered during the 20th century.

Cornelis Hofstede de Groot mentioned the four paintings in a catalogue raisonné in 1910, but not much attention was given to these mentions as they seemed to be atypical in Hals’ oeuvre. This changed in 1958, when Irina Linnik, an art historian for Odessa Museum of Western and Eastern Art, rediscovered the paintings of St. Matthew and St. Luke. These two paintings can still be seen in the Odessa Museum of Western and Eastern Art in Odessa. In the 1970s, Claus Grimm identified the painting of St. Mark, which is now in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. The Getty Museum paid $2.9 million for St. John the Evangelist in 1997, when it was rediscovered by Brian Sewell when the painting was brought in for evaluation at the auction house Sotheby’s. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas.

Where? Gallery 213 of the Cleveland Museum of Art

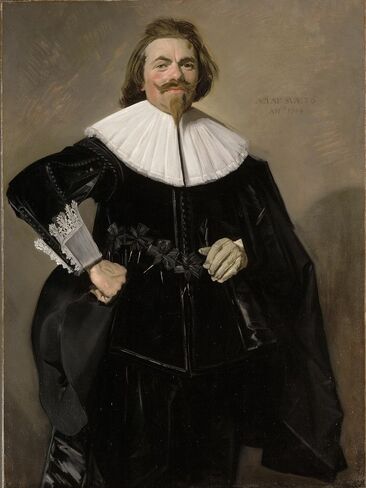

When? 1634 Commissioned by? Tieleman Roosterman and his wife Catharina Brugmans What do you see? The 36-year old Tieleman Roosterman looks at us with a serious and confident expression. He is painted in three-quarter length. Hals pays careful attention in painting his costume, which is not surprising given that Roosterman was an international clothing merchant. Roosterman wears a doublet, which is a short, close-fitting padded jacket. The jacket is decorated in the middle with metal or silver decorations. On top of the doublet, he has a big white ruffled collar. He has slashed sleeves, and on his right sleeve, he has a white cuff with lace edges. He has a glove on his left hand. He wears black breeches, which are a 17th-century type of pants that run just below the knee or till the ankles. In his right hand, he holds a large black hat made of beaver fur (such hats were popular during that time as they could be turned into a variety of shapes). All the items that Roosterman is wearing were very fashionable during his time. Inscription: To the right of Roosterman’s head, Hals included an inscription reading “AETAT SVAE 36 ANO 1634”. This means that Tieleman Roosterman was at the age of 36 at the time of the painting and that it was painted in 1634. Roosterman and his wife, Catharina Brugmans, commissioned Hals to paint a portrait of both of them to celebrate their third wedding anniversary. The Portrait of Catharina Brugmans is in a private collection. When the Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman was auctioned in 1999, it also included a coat of arms and a crest above the inscription. However, by then it was known that the coat of arms contained a pigment that was only available almost a century after Hals painted it. Thus, the coat of arms was removed from the painting by the Cleveland Museum of Art to show its original composition.

Backstory: The Cleveland Museum of Art acquired this painting in 1999 for $12.8 million, a record for a Frans Hals painting at that time. Saint John the Evangelist held the previous record. This work by Frans Hals was sold in 1997 for $2.7 million to the Getty Museum.

Who is Tieleman Roosterman? A rich textile merchant from Haarlem, The Netherlands. He operated internationally and specialized in fine linen and silk. He was born in 1598, married in 1631, and died in 1673, all in Haarlem. Together with his wife, he baptized ten children. Tieleman Roosterman is probably also the model for The Laughing Cavalier painted in 1624 by Frans Hals. This painting is in the Wallace Collection in London.

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was born at the end of 1582 (or early 1583) in Antwerp, Belgium, and died in 1666 in Haarlem, The Netherlands. He painted many portraits and was a true specialist in characterizing his subjects. At the beginning of his career he created more colorful paintings but when he got older the colors he used became darker. Many artists (including Van Gogh) admired the many shades of a single color that he used in his works, and the current painting of Tieleman Roosterman is already a good example of Hals using many shades of black.

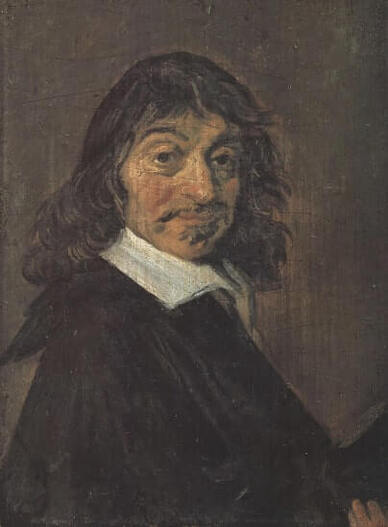

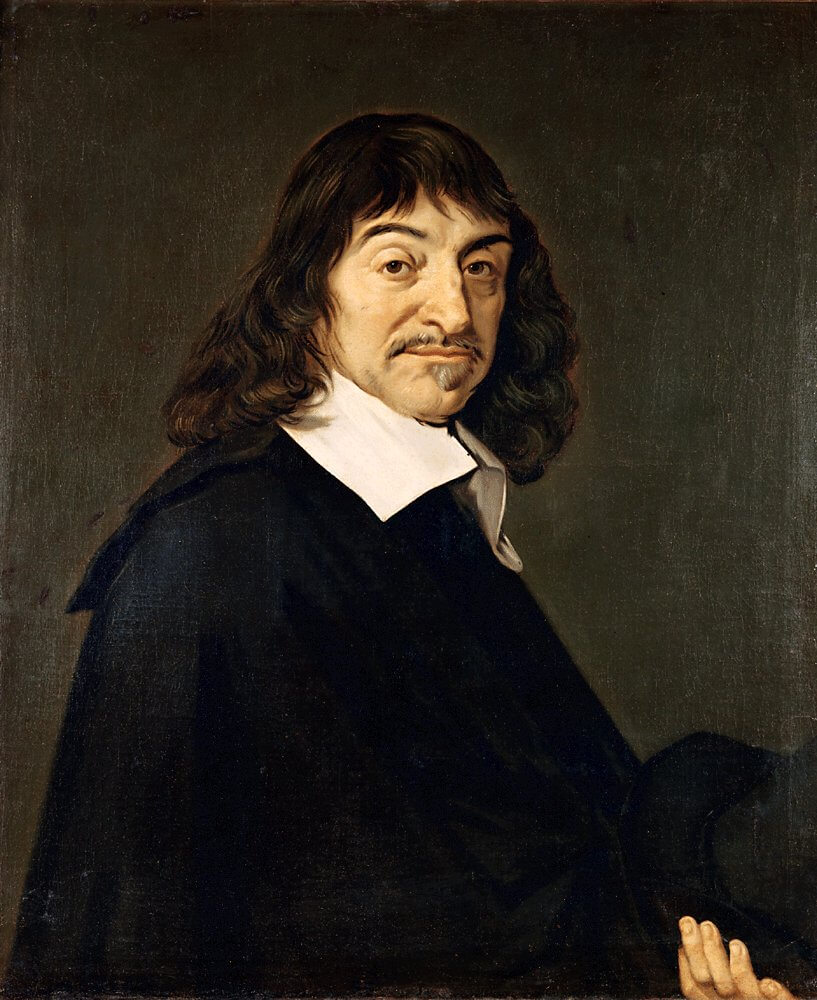

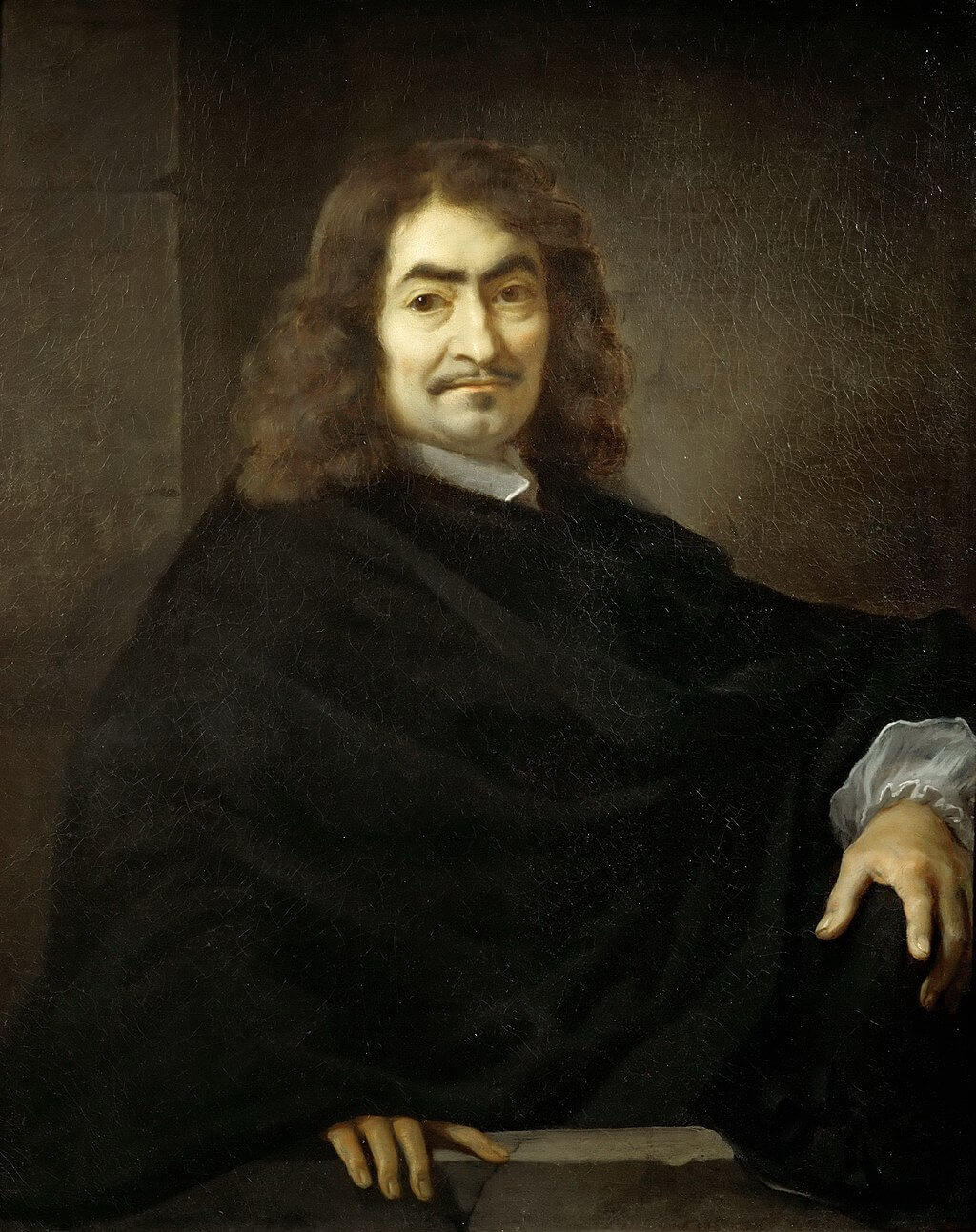

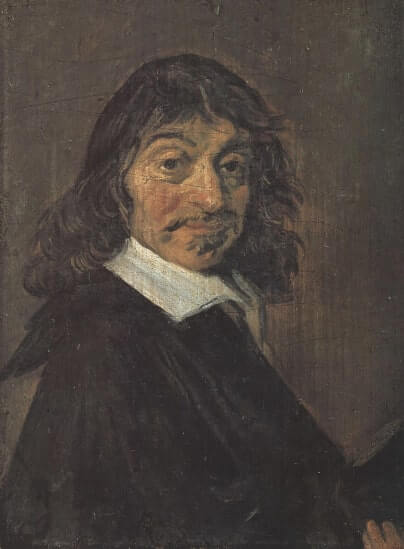

Fun fact: This painting was sold in 1999 to the Cleveland Museum of Art by the Austrian branch of the Rothschild family. In 1999, the Austrian government returned many items to the Rothschild family after the Nazis seized these items 61 years earlier. Before 1999, most items were on display in Austrian museums. After their return, the family decided to put many of the items up for sale because their houses were not big enough to properly display all the items. The painting of Tieleman Roosterman was sold with two other paintings by Hals and many other historical items at the auction house Christie’s in London. Interestingly, among the bidders for the items in the collection were several members of the other branches of the Rothschild family (they form a large and very wealthy family with branches all over Europe). It was reported that members of the French and British branch bought some of the items during the auction. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas. Where? Gallery 210a of the Statens Museum for Kunst When? 1649 Commissioned by? Probably Augustijn Bloemaert, a Catholic priest and friend of Descartes. What do you see? A portrait of the 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes. Hals paints him in three-quarters view. Descartes looks at the viewer with a confident, thoughtful, and inquisitive expression. The fingers of his left hand are visible in the bottom right. He holds his had in this hand. Someone has scratched this portrait by Hals after he completed it. There are zigzagging scratches in Descartes’ face. Probably this was done by someone who did not agree with some of the revolutionary ideas of Descartes. Backstory: In 1648, while Descartes lives in the Dutch Republic, Queen Christina of Sweden invites René Descartes to Sweden. Descartes accepts the invitation but does not move right away to Sweden. One of Descartes’ Dutch friends is the Catholic priest Augustijn Bloemaert. He is afraid that he may never see his friend again and invites Descartes to Haarlem where he lives. Being familiar with Frans Hals, Bloemaert commissions Hals to paint a portrait of Descartes. However, Descartes does not have much time to sit, and Hals needs to paint the portrait quicker than he usually does. He decides to use a small wooden panel of 5.5 x 7.5 inch (14 x 19 cm). It is the smallest painting he created during his life that was not on a copper background. Other Portraits of Descartes: Several versions of Hals’ portrait of Descartes are known, though Hals has painted only one of them and the rest are copies. One of those copies hangs in the Louvre. For a long time, the Louvre thought that they owned the original portrait by Hals, but nowadays the majority of art experts believes that the original is in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen. Hals was not the only one who portrayed Descartes. Between 1642 and 1649, the French painter and engraver, Sébastien Bourdon, also painted a portrait of Descartes. Compared to the painting of Hals, Bourdon’s portrait is static and lifeless. It is not surprising that Hals’ portrait of Descartes is the portrait that most people have in mind nowadays when thinking of Descartes.

Who is Descartes? René Descartes (1596 – 1650) is one of the greatest philosophers and scientists ever. He was born in France and lived in the Dutch Republic between 1628 and 1649.

In 1641, he published his influential book Meditations on First Philosophy. In this book, he figures out what can be known for sure. Descartes describes that people cannot trust their senses. People acquire knowledge through their senses, but they can be deceiving. Descartes asks himself questions about all sorts of beliefs, and if he even finds the slightest amount of doubt, he removes that belief from his mind. The result of that exercise is that only mathematics is true. Using that base level of knowledge as a starting point, he starts to build up his knowledge again. He argues that a person has to exist by writing “cogito, ergo sum” (I think, therefore I am). Through the publication of this book and his other books, Descartes became one of the most influential philosophers ever. Who is Hals? Frans Hals was born by the end of 1582 or early 1583 in Antwerp, Belgium. He died in 1666 in Haarlem, The Netherlands. He was a very talented and productive painter. About 80 percent of his works consists of portraits, among which The Laughing Cavalier from 1624 in the Wallace Collection and his 1634 Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Hals had a loose painting style, which means that he used relatively few brush strokes to depict something. You can often see the brush strokes in his paintings and particularly so in his Portrait of René Descartes.

Fun fact: Soon after Hals portrayed Descartes in 1649, Descartes leaves for Stockholm to teach Queen Christina of Sweden. Descartes has to wake up very early there to teach the queen at five in the morning. This made him fairly miserable because Descartes was used to waking up late, around noon, most days. The reason was that he believed that the best thinking could be done while in bed.

At a young age, Descartes already convinced his teachers that he should only leave bed very late. He was often sick, and some extra sleep was beneficial to his health. He used this time in the morning to think and reflect on his ideas. Descartes’ time in Sweden was not successful. Besides his early mornings, the Swedish Winter had a negative impact on his health, and he died in February 1650. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster

Where? Hall 11 of the Main Building in the Pushkin Museum

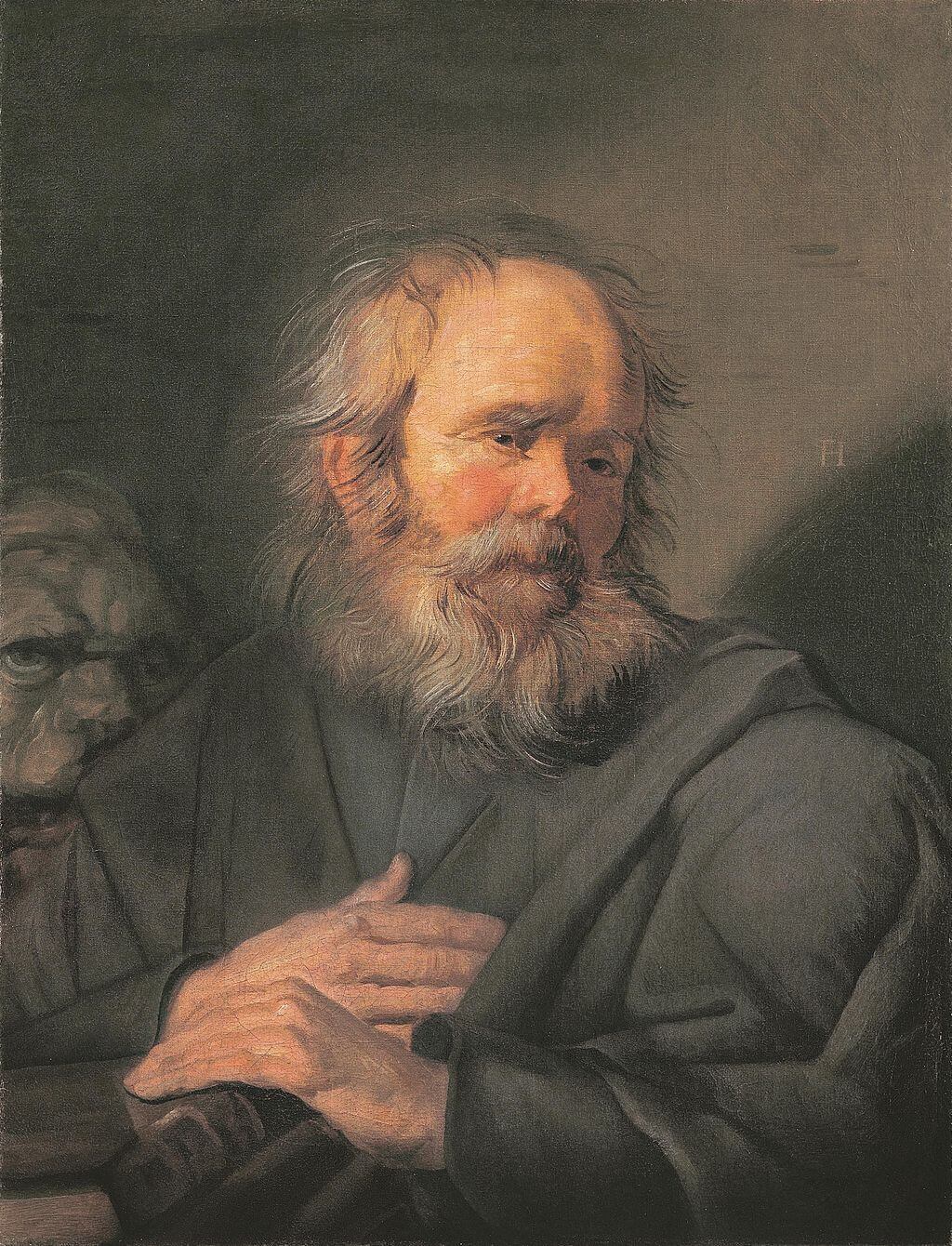

When? 1625 Commissioned by? Unknown What do you see? Saint Mark, the writer of the Gospel of Mark dressed in a nice dark blue cloak. His face is illuminated by the light that comes from the left. His beard is long and somewhat messy and his hair is unkempt. His hands are beautifully painted. Saint Mark is in his thoughts with his right hand against his chest and his left hand resting on top of some books.

Backstory: This portrait is part of a series of four depicting the four evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The paintings of Saint Matthew and Saint Luke are in the Odessa Museum of Western and Eastern Art in Ukraine. The painting of Saint John the Evangelist is in the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

The paintings on the four evangelists were acquired by the Russian Empress Catherine II for the Hermitage Museum in 1771. One ship containing most of the paintings sank and the second one, containing the works of Frans Hals, got damaged on the way from The Netherlands to Saint Petersburg but reached its destination. In 1812, these paintings were brought to the Ukraine to decorate some churches, but during the transport the four paintings got separated, and it is unknown what happened to them. Saint Mark was rediscovered in 1972, and in 2013 the Pushkin Museum acquired it.

Who is Saint Mark? John Mark was an assistant of the apostles Paul and Barnabas who he joined on their missionary journeys in the first century AD. He was both a friend and an interpreter for these two apostles.

In early Christianity, John Mark was considered to be the writer of the Gospel of Mark. However, nowadays, there is serious doubt on whether John Mark was indeed the author of the Gospel of Mark. One of the reasons for this is that John and Mark were very common names during those days and so there can be many other people who could be identified as the author of the gospel. Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was born in 1582/1583 in Antwerp, Belgium and died in 1666 in Haarlem, The Netherlands. He is known for his portraits and his lively and colorful depictions of militia (local armies of non-professional soldiers). His paintings on the four evangelists are not very representative of him as these are his only (known) religious paintings. His work was forgotten a bit after he died, but at the start of the Impressionist movement in 1860, Hals was rediscovered and has only grown in popularity since. Nowadays, Hals is considered to be one of the prime examples of painters in the Dutch Golden Age, together with Rembrandt and Johannes Vermeer. Fun fact: In 1955, this painting was anonymously sold as a work of the Italian painter Luca Giordano. In 1972, the painting was up for auction at Christie’s as a work from an anonymous painter with the title ‘Portrait of a Bearded Man.’ However, the German art critic, Claus Grimm, figured out that this painting was the missing painting by Frans Hals of Saint Mark. This was not an easy task as the painting had substantially changed as you can see in the first picture below. In the 19th century, someone had painted a large white pleated collar around the neck of Saint Mark to make it look like a Baroque painting. Moreover, the painting had lost all its color. The second picture below shows how the painting looked after an initial rigorous restoration. It is great to see how the picture subsequently has been restored to what we can see it today. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster.

Where? Room 17 of the Frans Hals Museum

When? 1611 Commissioned by? Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius What do you see? A life-size portrait of the 77-year old Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius. Frans Hals portrays Zaffius with his grey beard and mustache. Zaffius wears dark clothes with a fur cloak on top, a white collar, and a black cap. Hals paints him with a fairly serious expression. Zaffius looks to the left, which is the area where the light is coming from. Most of the face of Zaffius is illuminated by the light, and Hals uses darker colors to paint the left side of the face that is not in the light. Hals applies the paint smoothly and pays careful attention to the details in the portrait. However, compared to his colleagues, Hals somewhat broader brush strokes. Backstory: Frans Hals was 28 years old went he created this painting. He had only started as an independent artist the year before and was primarily working as an art restorer for the local guild of painters. This was the first commission that he received, and it was a great opportunity for Frans Hals to kickstart his desired career as a painter. He paints the portrait of 22 x 16 inch (55 c 41 cm) on a wood panel, which is the most popular medium for portraits of relatively small size. Who is Zaffius? Jacobus Hendricksz. Zaffius was a rich Catholic pastor, miniature painter, and environmental activist. Two years before he commissioned Frans Hals to paint his portrait, Zaffius had donated a considerable sum of money to expand an almshouse in Haarlem with five rooms. Jacobus Zaffius asked Hals to paint his portrait for the regent’s room of the almshouse. Zaffius was the official for the Catholic Church in Haarlem, even though the Catholic Church was officially forbidden. Who is Hals? Frans Hals was born in 1582/1583 in Antwerp, but his parents moved to Haarlem when Frans was about four years old. He would stay all his life in Haarlem where he would die at age 84. Frans Hals was a revolutionary painter. His broad and loose brush strokes were very different from other Baroque painters, and he was considered as one of the best painters in Haarlem during his life. He primarily focused on portraits, and about 80% of his surviving oeuvre consists of portraits of upper-class people. Among his more famous portraits are his Portrait of René Descartes in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen and the Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Fun fact: During his career, Frans Hals constantly struggled with the tradeoff between following his revolutionary artistic ideas and fulfilling the wishes of his commissioners. Hals liked to use loose brush strokes and omit some traditional details from his portraits. By doing this, he was better able to bring out the personality of his sitter.

However, his commissioners were often not ready for Hals’ innovative approach, and Hals also had to make some money to support himself and his family. Early in his career, Hals was more willing to listen to the demands of his commissioners and thus make more traditional portraits. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster

Where? Gallery 630 of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

When? 1616 Commissioned by? Unknown. Possibly a chamber of rhetoric or it was uncommissioned. What do you see? In the center, a woman dressed in a colorful and carnivalesque embroidered costume raises her right hand. She wears a wreath of laurel on her head and red beads around her neck and arms. Next to her are two comical characters. Six other characters surround the three central figures. Frans Hals painted these surrounding people very loosely. The people celebrate Shrovetide, a kind of Mardi Gras or carnival, in the days before Lent starts. To the left of the woman (from our point of view) is an older man grabbing her shoulder. He tries to say something to her. This man is called Peeckelhaering (which means pickled herring), and he can be recognized by two herrings hanging on a cord around his neck (see the two herrings next to the lower arm of the woman). Other items hanging on this cord are sausages, beans, a mussel, broken eggs, and a pig foot. In his right hand, he holds a foxtail. On the right is a man with a red cap looking at the woman in the center. He makes a sexual gesture with his hands. The table in the foreground contains various items, including a bowl with fish, an open can, half a loaf of bread, and deflated bagpipes. Backstory: This painting is also known as “Shrovetide Revellers.” Frans Hals probably depicts a play performed for Carnival. All actors in this play were men, and so the woman in the center is probably a man dressed up as a woman. She wears a wig and makeup. However, her hands are smaller than the hands of the men next to her. This feature either indicates that the man was built in a way that made it easy for him to dress up like a woman, or that she is a woman after all. Hals got inspiration for this painting from the works of Flemish artists like Rubens, Jordaens, and Jan Brueghel the Elder. He had seen their works earlier in 1616 during his 3-month visit to Antwerp. He took the modern Flemish ideas of a very busy composition and colorful figures and applied these to this painting. Hals painted the figures in the background using broad and loose brush strokes. Hals illustrates his trademark brushstrokes perfectly in the painting The Gypsy Girl in the Louvre, which he painted between 1626 and 1628. In 1907, Merrymakers at Shrovetide was bought for 89 thousand dollars by the American art collector Benjamin Altman. He left it for the Metropolitan Museum of Art after his death in 1913.

Symbolism: The two characters next to the woman in the center are two comical characters that played roles in the Baroque theater during that day. The man on the left (from our point of view) is Peeckelhaering. In his right hand, he has a foxtail, the symbol of a fool. A string with items hangs around his neck.

The man on the right is Hans Wurst. He makes an obscene gesture with his hands to the woman. Some of the items on the table are also sexual references. For example, the deflated bagpipes are another reference to the limited sexual potential of Peeckelhaering. What is Shrovetide? The Christian period of preparation for the six-week Lent. This period is strongly associated with Carnival. Shrovetide begins on the Septuagesima Sunday, the ninth Sunday before Easter. It lasts for 2.5 weeks and ends on Shrove Tuesday. The day after Shrove Tuesday is Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent. Shrove Tuesday is a day with two different faces. Some people use this day to self-reflect and figure out what sins they regret and how they can grow spiritually. Other people celebrate this day wildly, as it is the last day on which they can indulge in food and drinks.

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was a Baroque painter. He was born in Antwerp, Belgium, by the end of 1582 (or early 1583). At a young age, his family moved to Haarlem, The Netherlands, where Frans would spend the rest of his life.

During the year that Hals painted Merrymakers at Shrovetide, he also became a member of a local chamber of rhetoric called ‘De Wyngaertrancken’ (the vine tendrils). He did not participate in the performances of this chamber of rhetoric as he was a “second member,” which means that he merely admired the performances of other members. It shows his interests in depicting these plays even though his real specialty were the portraits that he painted. Among his most famous portraits are the Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman in the Cleveland Museum of Art and The Laughing Cavalier in the Wallace Collection in London.

Fun fact: Hans Wurst, the man on the right of the woman (from our point of view), was a comical character in 17th-century performances. Hans Wurst means John Sausage, and he can be recognized by the sausage dangling from his cap. He waved this sausage in front of his fellow players to make fun of them. Hans Wurst makes an obscene gesture. He puts the thumb of his left hand in between the middle and ring finger of his right hand, which form a circle. This is a gesture suggesting to penetrate the woman.

Interestingly, this gesture was not visible in the painting when the Metropolitan Museum of Art received it in 1913. Only after they cleaned the painting, the gesture became visible. During this cleaning in 1951, the six figures in the background were also discovered. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster

Where? Great Gallery on the first floor of the Wallace Collection

When? 1624 What do you see? A confident 26-year old officer portrayed in three-quarters view. He looks directly at the viewer while his left hand rests on his hip. He wears an expensive silk costume with rich and colorful embroidery. His coat is largely black with white, red, and yellow patterns. Unlike most of his other paintings, Hals put a lot of effort into the details of the costume. Moreover, he painted the elaborate white ruff around his neck and white lace on the sleeves in great detail. Around his waist, the sitter wears a black silk sash. He has a black hat with a broad brim with curly hair underneath. He has a goat patch and an expressive curly mustache. On the top right is an inscription reading “Æ’ TA SVA’ 26 A ͦ1624,” which is Latin for “aetatis suae 26, anno 1624.” This indicates that the sitter was 26 years old and that Hals painted this portrait in the year 1624. Backstory: There has been much speculation about the identity of the young man in this painting, but no consensus has been reached. Most people agree, based on his costume, that the man is probably an officer in one of the shooting guilds. One interesting theory is that the young man is Tieleman Roosterman, who is also the subject of the 1634 Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman by Hals in the Cleveland Museum of Art. In 1865, Richard Seymour-Conway, 4th Marquess of Hertford, paid £2,040 for this painting, which was the highest price paid for a work of Frans Hals at that time. However, for Seymour-Conway this was just pocket change as he earned about £250,000 per year. His son, Sir Richard Wallace – whose art collection forms the majority of the Wallace Collection – inherited the painting in 1870.

The Laughing Cavalier? The title of this painting is a bit of mystery. It was originally called Portrait of an Officer. In 1871, it was called The Cavalier at an exhibition in London. At an exhibition in 1888, it was listed under its present title, The Laughing Cavalier, but it is not clear why this title was chosen. While the officer has a confident expression, he is certainly not laughing. It is possible that before a cleaning of the painting in 1884 the officer appeared to be laughing more than after the cleaning. Moreover, there is no evidence that the sitter is a cavalier.

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder (c. 1582 – 1666) was a Dutch Baroque painter from Haarlem, The Netherlands. When Hals painted The Laughing Cavalier, he was quite successful and a respected painter in his hometown. While Hals primarily painted portraits, he occasionally liked to paint some happy characters that he met in bars or on the street. This was a great way for him to practice painting the emotions of his sitters which he could then use for his commissioned portraits. Whereas many other painters have a problem painting a genuine smile on the face of their subjects, this was one of the specialties of Hals. Almost effortlessly, he could paint the smile of a young child or a drunk man, the unrestrained smile of a crazy person, or the mischievous smile of a musician. This last kind of smile is nicely illustrated in The Lute Player by Hals in Louvre. Lesser-known about Frans Hals is that he also painted a few religious paintings. During the 20th century portraits of the four evangelists have been discovered. One example of this series of four paintings is Saint John the Evangelist in the Getty Museum.

Fun fact: Frans Hals liked to enjoy a drink in the tavern. In 1718, one of Hals’ first biographers, Arnold Houbraken, wrote the following story about Hals. His students repeatedly picked him up from the bar late at night to prevent any harm from happening to him on his way home.

When Hals arrived home, no matter how drunk he was, he prayed and ended by saying “Dear Lord, bring me to Heaven at a young age.” His students were concerned whether he meant this or not and decided to test him out. They drilled four holes in the ceiling above Hals’ bed and put some ropes through the holes which they attached to the bed. The next evening, after Hals had been drinking again, they put him in bed. Hals said the same prayer. After his prayer, his students pulled the ropes and lifted his bed into the air. Hals, who noticed that he was being lifted, proclaimed: “Not so quick, dear Lord, not so quick, not so quick….” Hals fell asleep and the students loosened the ropes such that Hals would not notice anything the next morning. Hals, who was unaware of the prank his students pulled on him, did not use that prayer again. Except for Houbraken’s story, there is no further evidence that Hals was a drunk and most likely this story is just a legend. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us