|

Where: Gallery 248 at the Art Institute of Chicago

When: c. 1893 Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 65 cm x 80 cm (25.6 x 31.5 in.). What do you see? At first glance, the tabletop, the basket of apples, wine bottle, plate of biscuits, apples tumbling across the tablecloth and surfaces, may appear to be a straightforward still-life painting but a longer look will show that it is much more than that. Cézanne had been rejected by the public for so many years that he had freed himself to see and paint to his own dictates. His still-life depictions are complex compositions that continue to provide the harmony and unity of his subjects that was so important to his philosophy of art, but he was experimenting at the same time. At first glance, we see a pleasing colorful painting that invites us in for a longer look. Cézanne, while showing himself and his viewers a kaleidoscope of perspectives, broke the rules of art with impunity. This painting provides a perfect example of what he did in order to portray our human visual perceptions that operate on so many levels in order to interpret our surrounding environment and what we see. Impossible Perspective? The longer look reveals a table that is impossible. The supports on the left and right sides are not the same height. The tabletop is not even on both sides and also not the same color. An extra tabletop can be seen on the right side. The back of the table on the left and right sides are also not on the same levels. We are looking at a variety of differing viewpoints. The table is tilted towards the viewer and on the left, yet another level supports the apple basket in a position that seems impossible as well. Does the wall support the basket? The green wine bottle is not symmetrical and leans slightly towards the left. Does it also support the basket? Even the biscuits on the plate provide differing views; we see both a side and top view at the same time. Cézanne has manipulated the biscuits by angling and elevating the two upper biscuits so we see two whole tops. There is a grey gap on the right side that creates a tilt in the edge of the upper back part of the table. It gives the impression that the right back part of the table is holding some of the fruit in place to keep it from rolling off into space. A pear at the edge of the gap also seems to act as a stopper. The folds of the tablecloth contain some of the loose fruits with a power that is stronger than simple cotton. Cézanne was known to impregnate his cloths with plaster of Paris to make them firm. Perhaps this is an example of that technique. A long grey fold that starts just right of the center of the painting, guides the eye into the scene and it provides a suggestion of depth, yet the cloth still seems to be about to fall from the table because of the illusion of a forward tilt. The feeling is augmented by the lack of a clear table edge on the left side. The wine bottle provides a vertical center that is surrounded by a variety of horizontal planes that do not interfere with the perception of the whole. Cézanne made clever use of grey tones on the wall, on the basket support, the plate of biscuits, the grey gap in the table on the right and the grey on the table in the front, plus the grey highlights on the cloth to unite all elements. Back Story: Paul Cézanne was 54 years old in 1893 and would only live another 13 years. His exploration of techniques, styles and mediums was extensive by this time and covered his full range of compositions and subjects. His progress over time is clearly visible whether he was painting a portrait, a landscape or a still life. His concerns centered on the artist’s interpretation and portrayal of a subject. His viewers should perceive all sides and the inside-out in their perception of harmony and unity in his works. He wanted his viewers to see and feel the wind in a landscape, find the personality in a portrait, and understand all sides of the objects in a still-life as he presented it. How we perceive visual stimuli was a major concern in all he did. Influence of Chardin: In his early years, Cézanne visited the Louvre and became familiar with the work of Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin. Chardin had been considered one of the most revolutionary artists of 18th century France, in particular having raised the lowly art form of still life painting to a level of popularity not known before in France. His desire to paint reality came from the Age of the Enlightenment. “Sensations of the mind” were being questioned. There was the belief that painters could “manipulate colors and shapes to induce particular responses in the viewer”. The American art historian Theodore Reff suggested the influence that Chardin may have had on Cézanne: “It would be hard to imagine the emergence of still life as a major category of modern art without the example of Cézanne from about 1875 on and equally hard to imagine his achievement without the revival of Chardin some thirty years earlier … Chardin did not use trompe-l’oeil to deceive by an optical illusion … his aim was to re-create the living, moving character of the vision of reality.”

Chardin tended to place his objects in a line, interacting with each other but separate. A slice of brioche and a bite of the cherries from the table is inviting. He always led viewers into his still-life by using a long object as above or a knife in order to emphasize the depth of the table. Cézanne used the same technique as both artists attempted to imitate reality on canvas. But Cézanne took the genre into another level of perception as described above and seen below.

The differences in the compositions of these two artists may be subtle but Chardin’s horizontal plane is absolute. The knife and the rumpled cloth lead the eye into each painting but Cézanne plays with our perceptions of reality as he tilts the plate of cherries to give us the best possible view. He was not afraid of deviating from the linear perspective that artists and collectors were so familiar with. Chardin’s stacked peaches provide the vertical element just as the green jar does in Cézanne’s work. Chardin’s perfect peaches even provide the fuzz, where Cézanne’s peaches have imperfections. His paint spills out of the outline, layers of green beneath are visible but when looked at from a distance, they remain realistic and appealing.

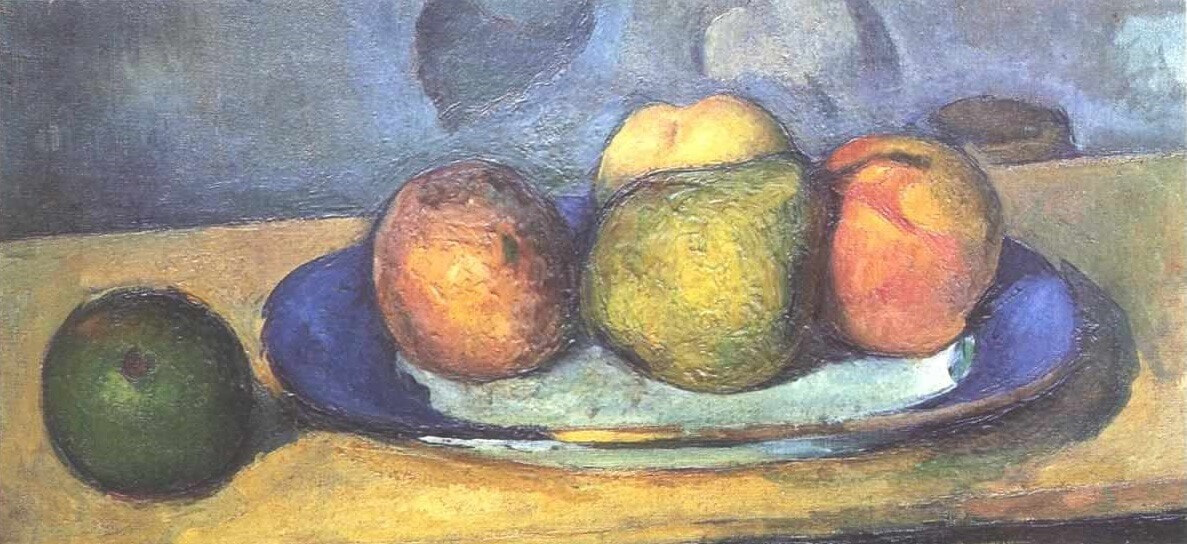

Still-Life Paintings by Cézanne: Cézanne said he wanted to “shock Paris with an apple.” Never before had everyday objects been presented in quite the manner in which he painted. He was always concerned with “color value, color schemes and creating form with color. His hatching style of brushstrokes and his outlining gave his objects their own subjective space” (Duchting, 2003). His Fruits on a Blue Plate seen above, reveals each technique. Tonally blue, simple color scheme of blues and yellow (blue and yellow make green), the distinctive brush strokes on the fruit, layered to give volume and form, and the final outlining to separate each object, yet he maintains their intimate relationships. There is a blue haze over the whole painting uniting the parts.

Still Life with a Ginger Jar and Eggplants, painted between 1893 and 1894, shows how the blue drapery with its patterns and folds gives volume and texture to the painting. There is a slight suggestion of a table on the left-hand side near the bottom but without that, the materials and objects look almost suspended in air. Cézanne integrates his geometric shapes of circles, triangles and domes to compose interesting pattern after pattern. The relationship between the ginger jar and the green objects catches the eye. The brownish pear behind the plate of fruit transitions the colors of the rum bottle and the eggplants so they are included in the grouping in a natural manner. The pear with its yellowish highlights, helps to keep the relationship with the plate of fruit and the lemon on its own, as integral to the work. Cézanne has tilted the plate to provide a good view of all the fruit but again disregards the rules of linear perspective as these fruits should be falling onto the floor. He keeps us off balance by painting an impossible table in the background. Legs may be intimated but we cannot see them, and the table should be falling too.

Cézanne worked slowly and each brush stroke was thought out a thousand times. To Gasquet (his young student and confidante), he said: “You have to get hold of these fellows … these glasses, these plates, they talk to each other, they’re constantly telling confidences.” The intensity and the love that he put into these objects is remarkable. Cézanne’s motifs may be still or appear quiet but he creates tension and suspense that draws an emotional response from his viewers. Again, to Gasquet, he said: “The eye must grasp, bring things together. The brain will give it all shape.”

Early Still Life Paintings: These two earlier still-life paintings from the 1860s are much more classical in composition and style. Like Chardin, his objects are in a relatively straight line. A knife in the first work guides the eye into the painting. It’s function to cut the bread is plain. The cloth is definitely resting on a table as we see the outline of it, unlike his later paintings. In the second painting we see a difference. His brush strokes slash across the pears, thick paint bursting the edges in places. It looks hurried and tense as can be seen in his early landscapes and narrative paintings. Nothing quite like this had been seen before in his contemporary world. He would not find success until much later in his life when his still-life paintings were finally admired by the general public.

Cézanne painted the same object again and again and, as one looks through his work, they become recognizable quickly. By 1877, his compositions are still following the rules. Plate with Fruits and Sponge Fingers (1877) shows the straight line of objects and their relationships with each other in a realistic manner. The biscuits here are straightforward and meet our visual expectations, unlike the initial painting above from 1893. In the following years, Cézanne worked diligently and constantly to present all the dimensions of our sensations on multiple levels so that he and we could see his objects in a new way. This was true of all his subjects, whether in a landscape, a portrait, or a still life.

Atmosphere: According to Hajo Duchting’s 2003 book about Cézanne, the artist also wanted to: “reproduce the atmosphere of things. The starting point and central motif of his still-lifes are fruits.” To Gasquet, again he described his thoughts. “I decided against flowers. They wither on the instant. Fruits are more loyal. It is as if they were begging forgiveness for losing their color. The idea exuded from them together with their fragrance. They come to you laden with scents, tell you of the fields they have left behind, the rain that nourished them, the dawns they have seen. When you translate the skin of a beautiful peach in opulent strokes, or the melancholy of an old apple, you sense their mutual reflections, the same mild shadows of relinquishment, the same loving sun, the same recollections of dew…".

Still Life With Basket of Fruit (1888-1890) shows various everyday objects. The ginger jar, a cream and sugar set, and the warm colors and tone of this painting are immediately comforting to look at. The chairs, the tables, the paintings on the wall are homely and inviting. Knowing how he felt about the fruit that he painted offers more sensation. Imagine the smells, the feel of the fruit and the desire to be in that room. Still, he played with the balance. The basket is too large for the table. The handle is not where we would expect to see it. The ginger jar is tipped forward, the tabletops and legs are not matched. The cream and sugar lean to the left and the creamer handle like the basket handle is not quite “right”. A large pear on the left is extraordinary and seems to be a weight to hold the table down. He painted in yellow and blue tones, creating a canvas full of relationships that are on different planes and levels. It is sensual: a basket of fresh fruit from the orchards, with the promise of a delicious dish of fruit with cream and sugar soon to come. The distorted whole enhances the pleasure of the painting.

Cézanne’s Legacy: Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin have become known as the Post-Impressionists, the artists who transitioned from the Impressionist movement into the Modern Art period. Instead of portraying purely visual stimuli, Cézanne, in particular, was attempting to put his mind and his perceptions on the canvas and it was Paul Cézanne who Pablo Picasso singled out when he said of him, “he is the father of us all”.

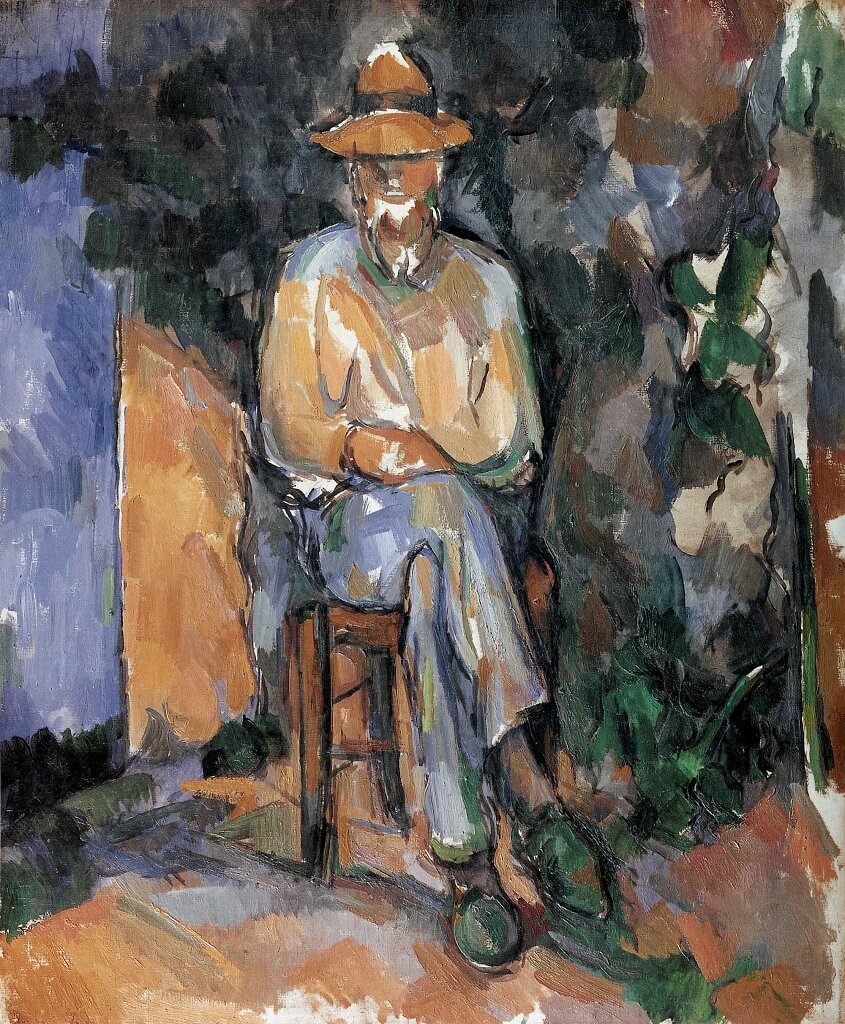

While Cézanne painted his colorful still-lifes, he continued to paint portraits and landscapes creating new views, different perspectives, and new ideas in all genres. He did say of himself, “I am the primitive of a new art”. He knew what he was doing was different. Portraits: Cézanne had hired Vallier to look after his garden in the Chemin des Lauves in 1902. He explained himself: “In today’s reality, everything is changing. But not for me. I am living in the town where I spent my childhood, under the eyes of people my own age, in whom I see my own past. I love above all things the way people look when they have grown old without violating tradition by embracing the laws of the present. I hate the effects those laws have.” His portraits are still, asking the viewer to stop and look at this man. In both paintings the man is at peace with himself, with who he is, with what he has done. The earth tones, the slashes of green, the deep dark of the foliage behind him and the wonderful straw hat all suggest peace with nature as well. Lurking in the back is the modern town as a reminder of the changes coming to the country. Cézanne’s colors flow, each brushstroke dependent on the next to provide the unity and harmony so spoken about in regard to his works. Each patch of paint reflects the one next to it as he builds his person in his environment. The Gardener Vallier (1906) seated on the chair is a looser composition, lighter and softer in tone. The painting has the same aura about it as its companion. The shapes formed by the color push towards the abstraction that followed. A frontal view with a slight turn to the right, allows us to see more of his body from differing angles. We can see these techniques in most of his works as he developed them over his lifetime.

Landscapes: Below are two landscape paintings by Paul Cézanne. In Gardanne (c. 1885), the building blocks are apparent and the Cubist beginnings are obvious. In Mont Sainte Victoire (1904), his style has developed much more. Cézanne was obsessed with Mont Sainte Victoire as he attempted to show every side and even the insides of this mountain. He painted it all his life and the painting below begins to take us into the world of abstraction. Each element in the painting is broken into pieces of itself but Cézanne has made certain they are still distinct.

Cézanne opened the door of possibilities for the Modern era artists with his unique use of colors and tones in his paints, the geometric shapes that were his building blocks and his compositions that changed the style of future art works. He perceived the world in a way not seen before and was brave enough to continue against all criticism and personal vitriol. Finally, he was at peace with his world and his work. He would be shocked now, to see the importance assigned to him.

Fun Fact: Recently, the Chief Conservator at the Cincinnati Museum of Art, Serena Surry, was examining, Still Life with Bread and Eggs (1865), as seen above. She became suspicious of what might be underneath and following x-rays, they found a “well defined portrait”. The staff are undertaking further investigation of the new-found work to find evidence as to whether it is a self-portrait of Cézanne or another individual.

Written by Carol Morse

References:

0 Comments

Where? Gallery 164 of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

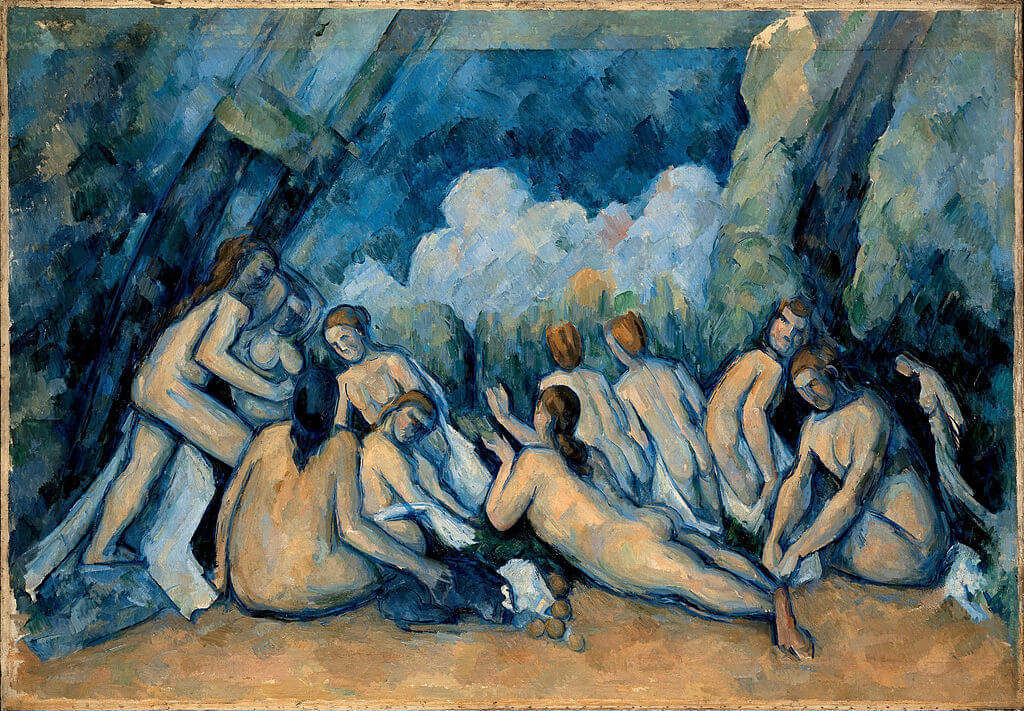

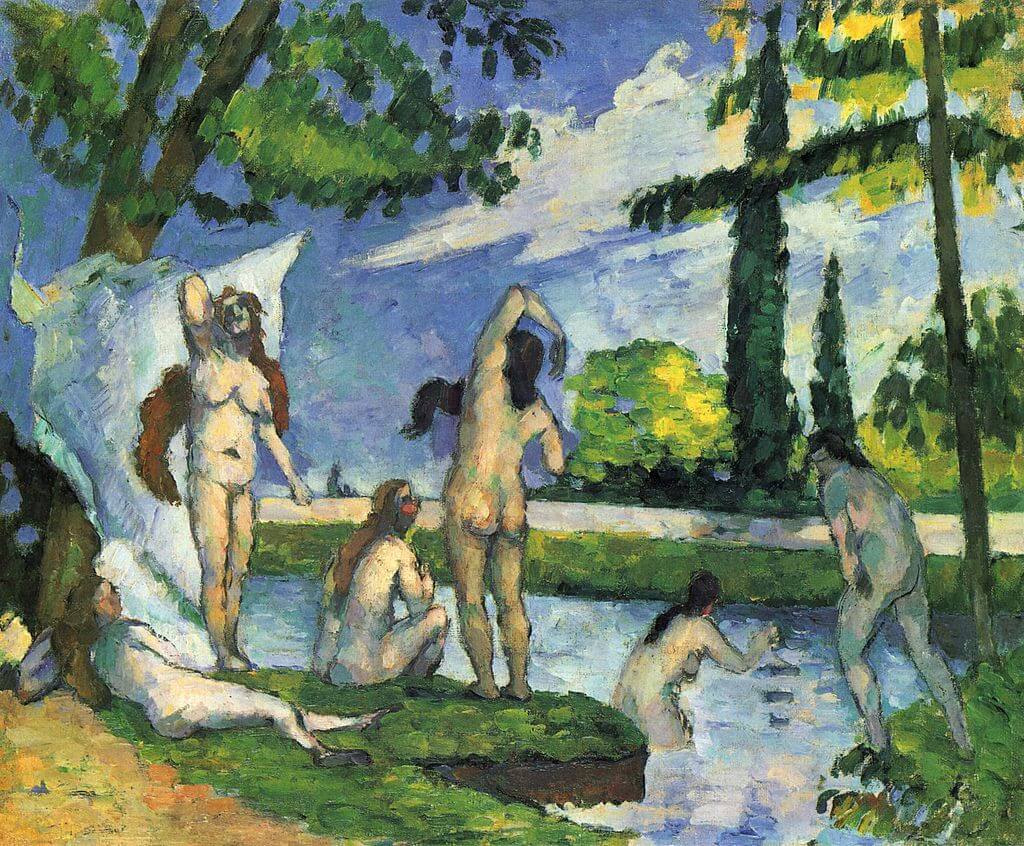

When? 1898-1905 What do you see? A group of women bathing near a river. There are two groups of women in the foreground; a group of six women on the left and a group of eight women on the right. In the middle of these two groups, you can see a river with someone swimming in it and on the other side of the river you can see the back of a man walking with a horse beside him. In the background, we can see a landscape with large cypresses, a church tower, and a blue sky with clouds. The middle of the painting has its own frame, bounded by the trees that are growing towards each other. Looking in more detail, the bodies of the women in this painting are not very realistic. They are malformed (look for example at the incorrect proportions of the tall woman standing on the left). In addition, none of the women in this painting has an identifiable face. Also, quite some parts of the human bodies are unfinished, and we can see the canvas underneath. For example, look at the horse or the woman lying on the right with her feet almost sticking out of the bottom of the canvas. Cézanne is showing the women more abstractly, and this painting had a big influence on the abstract paintings later in the 20th century. Backstory: Paul Cézanne worked for many years on this painting, and it was still unfinished when he died in 1906. He did not use any models for this painting but rather painted them from his imagination. During his life, he created about 200 paintings and drawings of nude bathers, but this painting is generally considered to be his best. Another version of the Bathers, painted around the same period as the painting in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is in the National Gallery in London. The Metropolitan Museum of Art owns a much earlier version of Bathers, which was created between 1874 and 1875 and shows them in a more typical impressionist style.

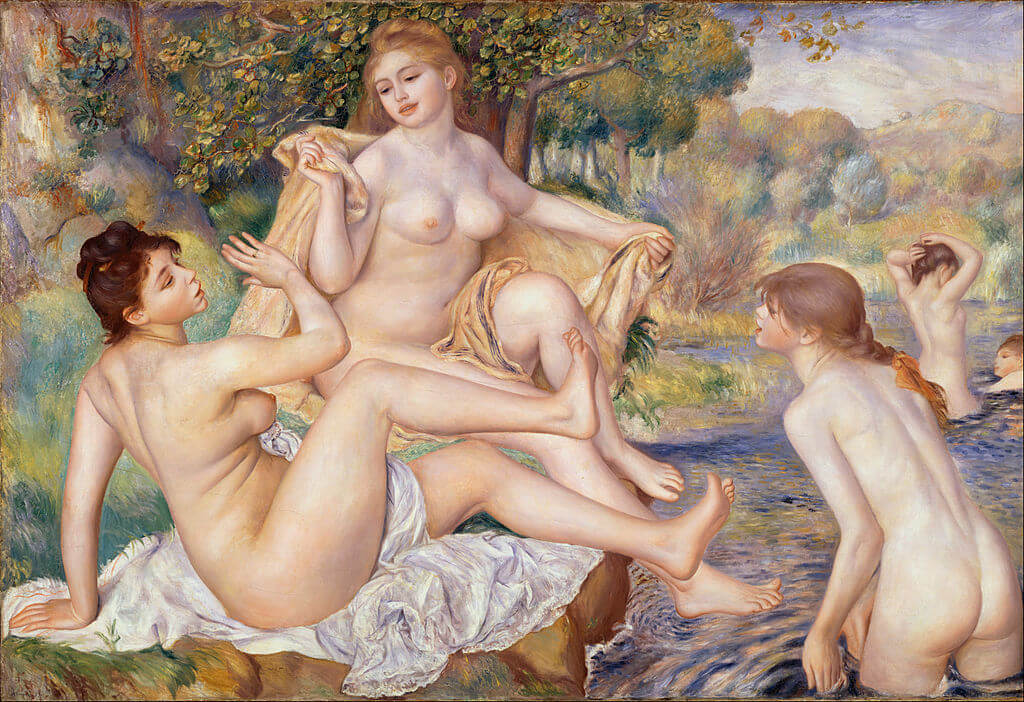

Bathers in art: This painting of Cézanne combines a landscape of Aix-en-Provence in the South of France with a classical bathing scene. It shows some similarities to the painting of Diana and Actaeon by Titian which also contains a bathing scene. Titian depicted the group of bathers in a triangular composition, which is also true for the two groups of bathers in Cézanne’s painting (as well as the large triangle formed by the trees). Finally, both paintings have some opening in the middle in which we can see a distant landscape. Bathers have been a subject that has inspired more painters over time. For example, the Philadelphia Museum of Art also shows a painting entitled The Large Bathers by Renoir.

Who is Cézanne? Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) was born in Aix-en-Provence in 1839 and also died there in 1906. In his twenties and thirties, Cézanne spent considerable time living in Paris, where he developed a friendship with Camille Pissarro. The father of Paul Cézanne was a banker and financially supported him during his life, such that he could focus completely on his art. He was an Impressionist painter, but later in his life, he developed some more abstract paintings. Picasso and Matisse were heavily influenced by this later work of Cézanne and considered him to be ‘the father of us all’.

Fun fact: This painting of The Large Bathers is considered to be the best work by Cézanne. The painting has had a big impact on many future artists. Cézanne painted this at the end of his life and it was still unfinished when he died at age 76. It is not very common that painters create their masterpieces at the end of their career. According to academic research, painters peak at the age of 42. In other words, painters create their masterpieces, on average, at the age of 42, and after that, the quality of their work generally decreases. The reason is that the creativity of artists decreases at a higher age and when they get old they are also often limited by physical ailments. For example, Sandro Botticelli created his masterpieces The Birth of Venus and La Primavera when he was between 35 and 41 years old, and he only died at age 64.

Written by Eelco Kappe

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

Where? The Courtauld Institute of Art in London

When? 1896 Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 64.0 x 81.3 cm. What do you see? A view of Lake Annecy and the Chateau de Duingt, situated in the French Alps, not far from the town of Annecy. The medieval fortress has been there since the 11th century. The view is from the opposite shore over the lake toward the castle. A large tree provides a frame on the left. The tree trunk disappears at the top edge, and the branches and boughs of the tree overhang the upper edge of the painting, their diagonal brushstrokes complimenting the background mountains and framing the view. The castle is situated at the center, with the lake in front and the mountains stretching into the distance behind the partially hidden buildings. Diagonal brushstrokes going in opposing directions create height and depth in the mountains. Highlights of rust, ochre, blues, and greens take the viewer deeper into the hills and valleys. The emerald/blue water is calming, with elongated reflections created with the edge of a palette knife. The light source comes from the left of the artwork and focuses attention on the reflections, tree trunk, and buildings. The contrast of the dark on the opposite side of the highlighting accentuates the importance of the objects in the painting. It is a peaceful scene, yet the composition and the colorings are somewhat startling at first glance. However, it is also a stirring work that asks the viewer to look harder.

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

Where? Barnes Foundation, Room 2, West Wall.

When? c. 1885 Medium and size? Oil on canvas, 65.0 x 100.3 cm. What do you see? A horizontal view of the city of Gardanne in Southern France. The panoramic view is controlled by the use of blue/gray tones to collect and join each building block of the painting. There are squares and rectangles that build the scene, creating the illusion of distance and leading the eye upward to the highest point where the important bell tower has been positioned in the center of the work. The trees and greenery form their own shapes that give more cohesiveness to the buildings. The outline strokes and the shadows delineate the red roofs and gently lead the eye up the hill. On the right-hand side, just above the top of the hill, are two towers that may be from factories beyond. There is an architectural feel to the painting, but the warmth of the colors dispels any coldness. The scene appears to lean slightly toward the left, which may add further interest to the whole.

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

Where? Musée d'Orsay

When? 1873 Medium and Size? Oil on canvas, 55 x 66 cm. What do you see? This painting is from the years Cézanne spent with the artists who would become known as the Impressionists. In the foreground, a right fork in the road leads steeply down a half-hidden pathway toward a large house with an attached outbuilding. On the right side of the painting is a bank that blends into a thatch roof attached to another building that could be part of the larger house or another house itself. The left fork in the road leads up the hill towards a group of trees in full leaf that bend to the right. The large house in the middle is partially hidden by tall, straight, leafless poplar trees. The construction of the center provides depth and distancing as the rooftops of the village houses lead further into the scene. Beyond the roofs and chimney tops, the green gardens or fields lead to more houses and the hilltop in the right center. The blue sky sets the tone for the whole painting. It feels monochromatic, but the painting is actually full of color. The white on the side of the house, the chimney in the distance, and the rooftops invite the eye further and deeper into the scene. On close examination, the blue of the sky can be seen throughout the painting and is reflected tonally in the rocks, the thatch, the village buildings, and the doorways and windows, as the blue blends, complimenting and connecting each section of the artwork.

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

Where? Städel Museum in Frankfurt

When? 1870–1871 Medium and size: Oil on canvas, 65.0 cm by 53.7 cm. What do you see? This is one of Cézanne’s early landscapes from his late “couillarde” period. He crudely described his own style at the time as ‘ballsy.’ Between 1862 and 1872, he painted in very dark colors, the paint applied thickly with a palette knife or thick impasto brush strokes. The strokes are visible and create texture that has a visceral feel to it. By zooming in on the painting, the navy-blue to almost black background is visible. It helps to create the sinister, unseen, section of the road. Light sources come from the yellow brush strokes slashed on the tips of the tree branches and white paint was applied on the road and rocks on top of the undercoating of darker navy/gray. The layering and alternating light/dark colors produce the perception of depth. Waves of brush strokes create the rocks on the right. The strokes appear to have been painted quickly, dragging and dropping bits of color as the brush flew across the canvas, almost in rage or frenzy. The brush strokes and the composition of the trees and rocks draw the eye upwards to the darkness. It is a powerful piece of art that pulls the viewer in, an invitation to experience either the lightness of the sunrise/sunset or to feel the impending darkness and with it a sense of foreboding. The rocks and trees loom over the road, a dare to walk or ride along it. The story choice is the viewer’s but with Cézanne’s paintings, there is always a demand for a reaction. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us