|

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

Where? Musée d'Orsay

When? 1873 Medium and Size? Oil on canvas, 55 x 66 cm. What do you see? This painting is from the years Cézanne spent with the artists who would become known as the Impressionists. In the foreground, a right fork in the road leads steeply down a half-hidden pathway toward a large house with an attached outbuilding. On the right side of the painting is a bank that blends into a thatch roof attached to another building that could be part of the larger house or another house itself. The left fork in the road leads up the hill towards a group of trees in full leaf that bend to the right. The large house in the middle is partially hidden by tall, straight, leafless poplar trees. The construction of the center provides depth and distancing as the rooftops of the village houses lead further into the scene. Beyond the roofs and chimney tops, the green gardens or fields lead to more houses and the hilltop in the right center. The blue sky sets the tone for the whole painting. It feels monochromatic, but the painting is actually full of color. The white on the side of the house, the chimney in the distance, and the rooftops invite the eye further and deeper into the scene. On close examination, the blue of the sky can be seen throughout the painting and is reflected tonally in the rocks, the thatch, the village buildings, and the doorways and windows, as the blue blends, complimenting and connecting each section of the artwork.

Motif: Cézanne painted it during a period he began to change his subject matter. No longer were his themes full of great drama or literary stories. He turned towards the ordinary. The subject became the "motif" (defined in art as a recurrent theme or subject in a particular artist's work). The whole meaning of the motif is attained only by the artist's interpretation of the subject. The painting indicates new subject matter, a unique manner of observation, and a change in the presentation that Cézanne was developing.

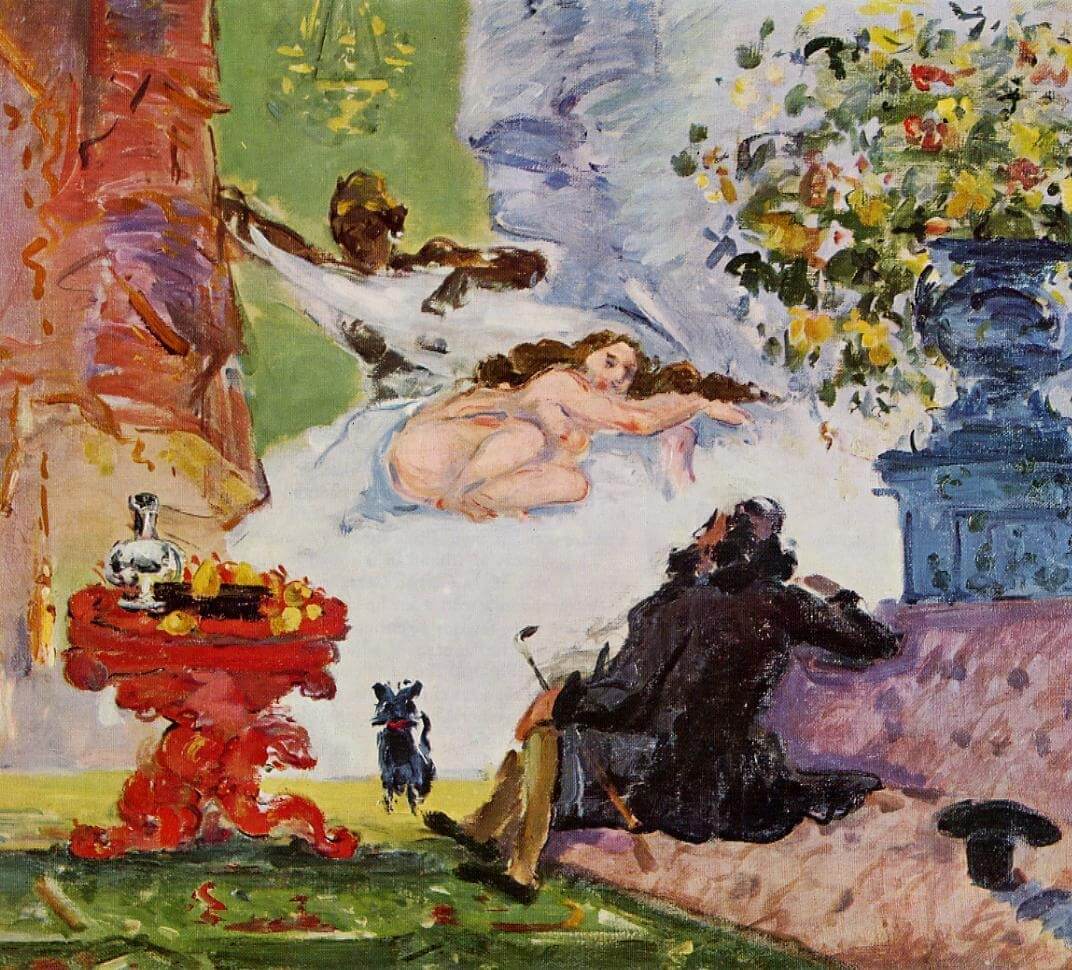

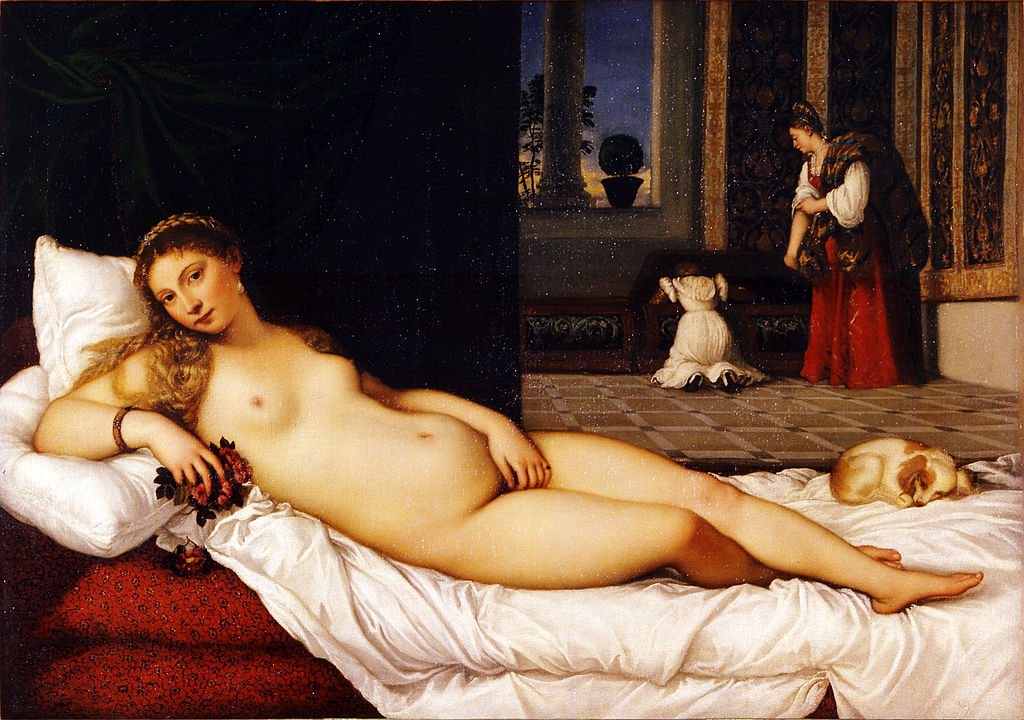

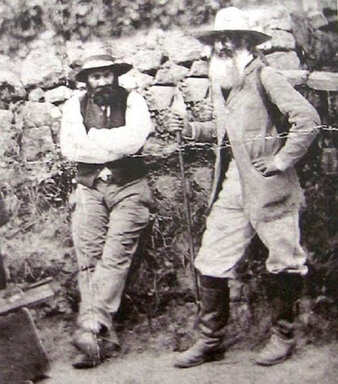

Background: No person was hanged in this house. It is not fully known why Cézanne gave the painting this title, but a man from Breton, named Penn'Du, reportedly owned the house at one time. His name is very near the French word "pendu," meaning "hanged man." As a young man, Cézanne had always enjoyed a play on words, so perhaps this was why he chose the title. Cézanne signed this work in the left-hand corner in red. It was exhibited several times during his lifetime with his consent, and these actions suggest that he was delighted with this painting. However, he was seldom pleased with his work, and he is known for the time he spent on each brush stroke and the many times he tore his work up and threw it away. The painting is now considered one of his masterpieces from his time with the Impressionist artists, and it fully demonstrates the changes in his work in the 1870s. A Modern Olympia: In 1874, Cézanne exhibited this painting in the first Impressionist exhibition at Nadar's studio in the Boulevard des Capucines in Paris. He also showed A Modern Olympia seen below. Manet had painted his Olympia in 1863 and exhibited it in 1865. It met with disapproval of the content, but the Salon jury accepted it for its classical appearance. Ten years after Manet, Cézanne painted his version as an homage to Manet's work, And just like with Manet's painting, the critics and the public were outraged. We can probably understand some of the reactions to A Modern Olympia, with its strange figures, loose brush strokes, and the insult it must have seemed to the original classical work by Titian but also as a reaction to Manet's work. Cézanne's was not art! They were also outraged by The Hangman's House. This was just a street, nothing special. How could it be art?  Cézanne (left) and Pissarro (right) in 1874. Cézanne (left) and Pissarro (right) in 1874.

With Pissarro and the Impressionists: In 1861, at the Académie Suisse, Cézanne met Camille Pissarro. Their acquaintance blossomed into a friendship in 1872–1873 when Pissarro asked Cézanne, his partner Hortense Fiquet and their young son, Paul, to join his family in Pontoise so they could paint in and from nature together. Pissarro was nine years older than Cézanne and had always been the wiser, stabilizing voice in the group known as the Impressionists. Both men recognized that they stood apart from the rest. Their approach to art was more unconventional, and criticism of their works was more virulent than most other Impressionists experienced.

In 1870 Cézanne and his small family had been spending time in L'Estaque, in the south of France, to ensure that Paul was not conscripted into the army to fight in the Franco-Prussian War. Cézanne had been hiding both Hortense and young Paul from his father because he was terrified his father would stop his allowance completely if he knew about his living arrangements. So if he went to Aix to work, he went alone and used the studio at the family home, Jas de Bouffan, just outside town.

At the end of 1872, they accepted Pissarro's invitation. The war was over, and they moved to a hotel in Pontoise, near Pissarro's flat. By early 1873 they moved to a house in Auvers. One of their neighbors was Dr. Paul Gachet (later famous as Van Gogh's doctor), who supported Cézanne and many up-and-coming artists by buying their work or providing financial help. Working alongside Pissarro in plein air, in combination with the encouragement of Dr. Gachet, Cézanne gradually changed his palette and techniques. Together, the two artists fed off each other's intellect and talents, and at last, the genius of Cézanne began to find a mode of expression. His palette lightened, greater precision can be seen in his compositions, and a much finer touch with detail is visible in his work from this period.

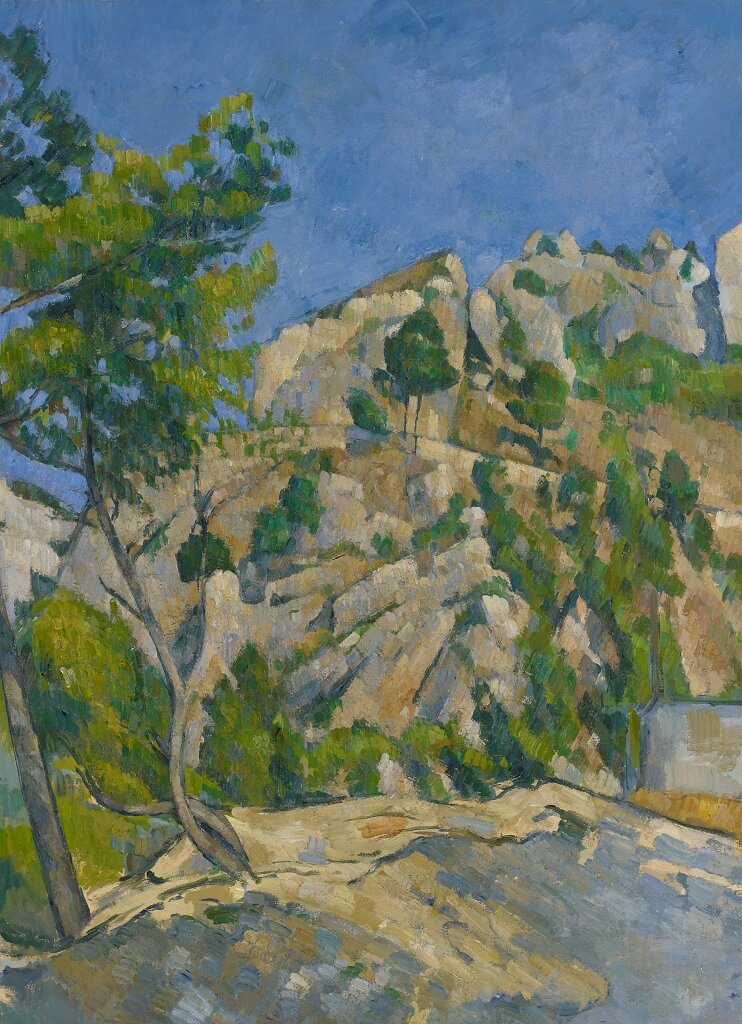

According to Sue Roe, in The Private Lives of the Impressionists: "from Pissarro, he learned to move outside the turmoil of his imagination. Pissarro taught him to control and harmonize his powerful emotions, and discipline his observations. Pissarro, now over forty, became something of a father figure, working painstakingly with Cézanne, who –somewhat astonishingly-listened to his advice…. With Pissarro, he discovered his own method of modeling forms and blocking in color, using color rather than contour to determine geometric form…. forms did not have to be drawn, they could emerge, if one would only look at the landscape and paint what he saw—the essential character of things." Still visible are his heavy impasto brush strokes that give a tactile feel to the work. Grainy effects can be seen in the roadway and the eves of the house in particular. The thousands of smaller strokes that provide layer upon layer of paint and composition draw the eye into and over the whole scene. The solidity that is paramount in his paintings is clearly visible. He was never drawn entirely into the Impressionist theories or styles but used some of their techniques. Ever present are the palette knife strokes that smooth and soothe his scenes. The blocking of colors and shapes in this painting are a glimmer of what he would do in the future. Traveling and Inspiration: For most of his career, Cézanne traveled up and down France, from Aix to Paris, and the other way around. Most of his motifs came from the areas surrounding these two centers: In the south, his home in Aix, "Jas de Bouffan," L'Estaque near Marseille was a favorite, Gardanne another, and his most famous motif, Mont St. Victoire, is north of Marseille. In the north of France, his learning grounds included Pontoise, Auvers-sur-Oise and the surrounding hills and valleys, and the banks of the Seine. Cézanne's Style: By 1877, Cézanne realized that the aims of the Impressionists were not the same as his own. The Impressionists were concerned with the effects of light and reflected color and how that was perceived both by the artist and viewers. Cézanne was committed to form, volume, movement, and the natural, as he perceived it. Long before the psychologists mapped the brain to discover preferred visual stimuli, Cézanne was plotting his own brain, asking what it liked and attempting to reproduce that on paper or canvas. He said: "Nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, and the cone." He used geometric shapes to find harmony, each brush stroke creating a dependency on the next to complete each painting. As you look at the paintings below, evidence of how he developed his techniques are present in each work. Triangles, curves, arches, and squares are present in abundance. Trees join at the top to create an arch. Foliage is blocked with brush strokes and colors, seen in the chestnut trees at Jas de Bouffan. Rectangles and squares and domes create a mountain.

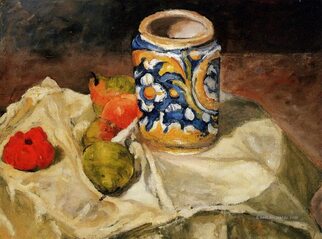

Cézanne painted the places and things he loved, caring for each inch and arranging it to suit his standards. If a tree was not where he wanted it, he moved it. Or if a house did not sit the way that appealed to him, he would turn it around or place it across the street. In his paintings, geometric shapes are used repeatedly in combinations carefully constructed, so the viewer is unaware of them without intense focus. At first, his paintings seem straightforward and plain, moving towards simplicity, but with some additional study, the complexity is apparent and the beauty even more rewarding. He applied his paint on the diagonal to attain the sensation of movement. His trees come alive, and one can almost hear the wind whistle through the boughs. His still lifes were constructed in the same manner, and every fold in the cloth he placed on the table was planned, the placement of each item carefully thought out to move an eye through the work without distraction. Light and dark color contrasts illuminate his paintings.

The tree, a cylinder that bends to the left, gives the curve that is a mound, the triangles of the rooftops, the parallel tree trunks, and his tonal harmonies were taking Cézanne in another direction.

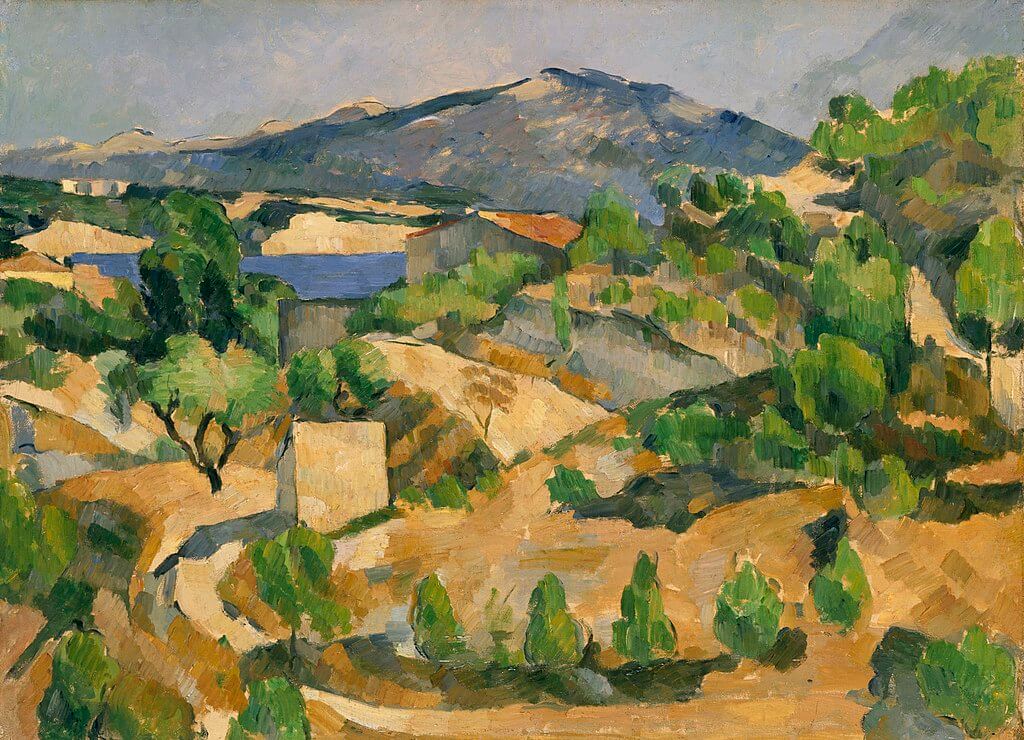

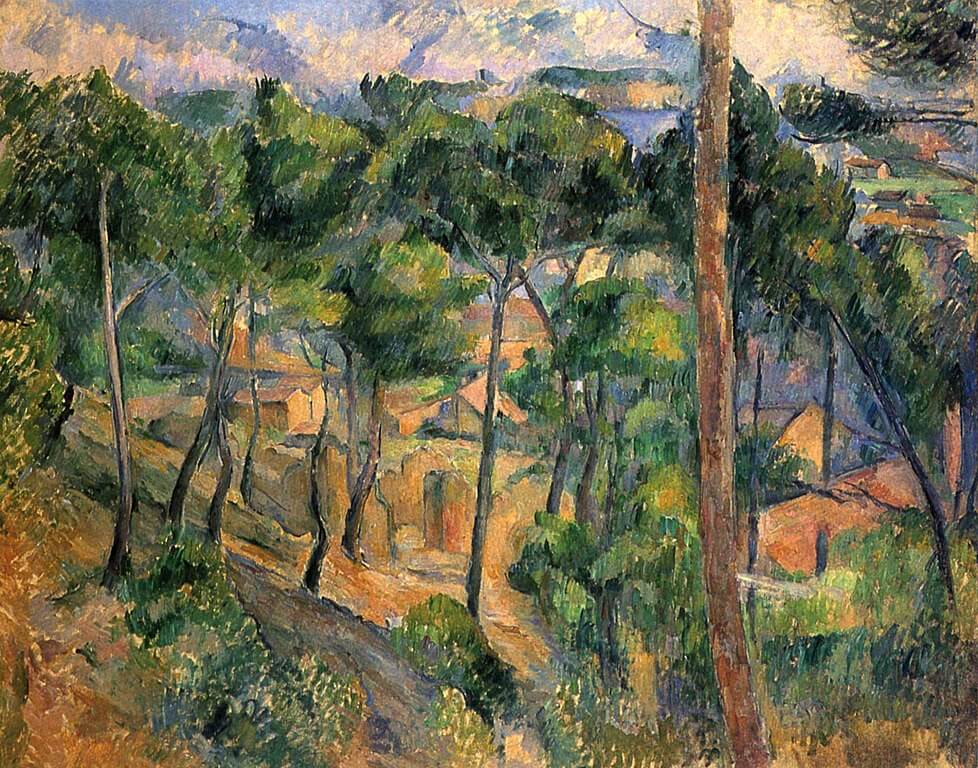

Construction Period: The two paintings below from 1880 and 1883 lead to his "construction period" from 1883 to 1895. Cézanne used color to build forms that still create geometric shapes, but each leads to the next shape, and each shape depends on the others to create the scene. He takes us down a steep hill into L'Estaque, but the houses are discovered only by their suggestion of shape. A patchwork of color hides and exposes the scene at the same time. Cézanne was just beginning to open the door that Gauguin, the Fauves, Braque, and the likes of Van Gogh and Picasso would blow wide open in the Modern era.

Written by Carol Morse

References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us