|

Four Stages in Cézanne's Career: This post is part of a series of four providing an overview of the development and change in Paul Cézanne’s approach to his landscapes from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Each part is concerned with a time period of approximately 10–12 years. Scholars have recognized each section and have named them for convenience of recognition.

Where? The Courtauld Institute of Art in London

When? 1896 Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 64.0 x 81.3 cm. What do you see? A view of Lake Annecy and the Chateau de Duingt, situated in the French Alps, not far from the town of Annecy. The medieval fortress has been there since the 11th century. The view is from the opposite shore over the lake toward the castle. A large tree provides a frame on the left. The tree trunk disappears at the top edge, and the branches and boughs of the tree overhang the upper edge of the painting, their diagonal brushstrokes complimenting the background mountains and framing the view. The castle is situated at the center, with the lake in front and the mountains stretching into the distance behind the partially hidden buildings. Diagonal brushstrokes going in opposing directions create height and depth in the mountains. Highlights of rust, ochre, blues, and greens take the viewer deeper into the hills and valleys. The emerald/blue water is calming, with elongated reflections created with the edge of a palette knife. The light source comes from the left of the artwork and focuses attention on the reflections, tree trunk, and buildings. The contrast of the dark on the opposite side of the highlighting accentuates the importance of the objects in the painting. It is a peaceful scene, yet the composition and the colorings are somewhat startling at first glance. However, it is also a stirring work that asks the viewer to look harder.

Backstory: Cézanne stayed in Talloires by Lake Annecy when he painted this scene. He viewed it as something that "would lend itself to the line-drawing exercises of young ladies. Certainly, it is still a bit of nature, but a little like we've been taught to see in the albums of young lady travelers." His version of the scene could not be further from that description.

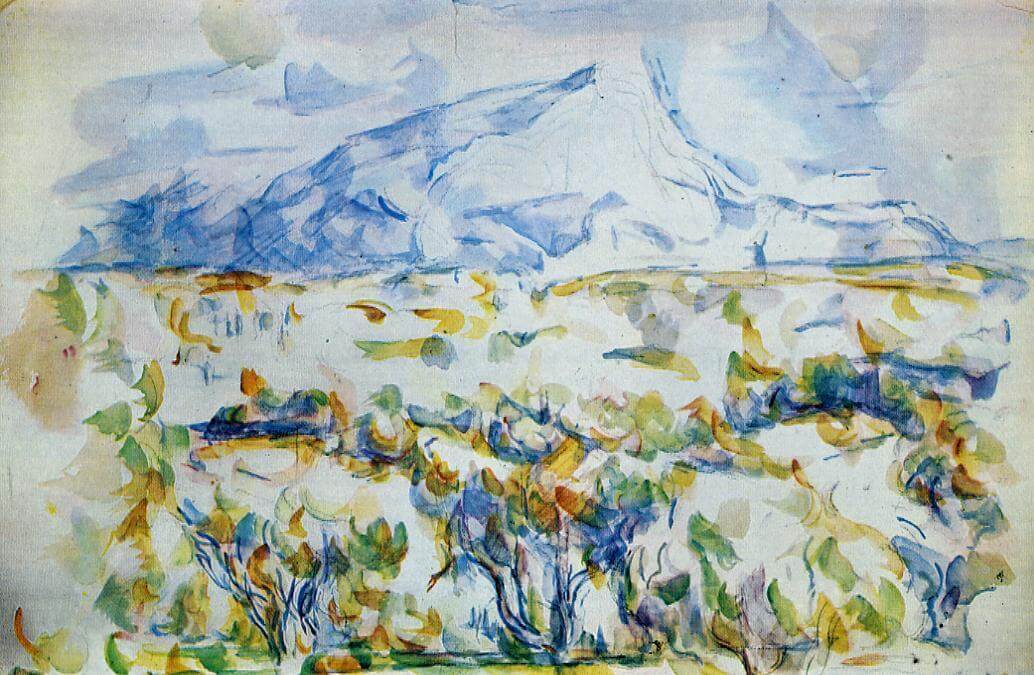

In the last ten years of his life, Cézanne painted with the same passion, the same striving for the expression of his subjects, and the same intensity that he had always had. He had combined or synthesized his ideas of nature and art. Harmony was fundamental to him, and the underlying structure, geometric forms, volume creation, color sense, and style culminated in creating the permanence, the unchanging world he desired in his beloved Provence. The structure he created in his compositions allowed him fluidity, but he continued to develop perceived volume and space. He captured nature in a way that it was synthetic, different from what is actually there but representing it just the same. Émile Zola had described him "as a genius who never matured." Lake Annecy and other paintings in this period prove him wrong. Cézanne sought the "essence" of nature, and he aimed to show that on canvas in oil paintings, drawings, and watercolors, In Lake Annecy, he gives us the very essence of the scene. We viewers probably want to be in the blue/green areas. Cézanne lets the viewer make their choice. Do we want to be by the big tree trunk, looking across the lake, on the water in a boat, in the water feeling its coolness, off in the mountains looking back on the lake, or in a room in the castle? Mount Sainte-Victoire: The diagonal strokes and color patches in The Lac d'Annecy (1896) are like the work of a diamond cutter who slowly exposes each facet of a gem to release the brilliance that is hidden inside. This 1896 painting demonstrates the direction he was taking and helps us understand what he would pursue with his works of Mount Sainte-Victoire. In 1895, Cézanne had his first solo exhibition at Vollard's Paris gallery. Vollard had bought several of his paintings in 1894 at an estate auction. At long last, an art dealer had taken serious notice of his work. The exhibition the following year included some fifty pictures selected by his son. Fellow artists like Degas, Monet, Pissarro, and Renoir expressed their esteem for his work, but the public remained largely unresponsive. His father's death in 1886 had made him financially independent. He was free to pursue his art without the approval of anyone. He withdrew more into himself, but he did speak about art and his theories to other younger artists who would listen. His fascination with Mount Sainte-Victoire was born in his youth when he could view the mountain from his home in Aix. The following version, Mount Sainte-Victoire (1867), is from his dark period.

Impasto brush strokes on top of each other produce layers that give depth, as we saw in The Road with Trees in Rocky Mountains (1870). White is slathered generously over the rocks and hills, and the tree branches and grasses below are menacing in the same manner. It is a messy, hurried version with each brush stroke visible. The hills and the sky beyond give a threatening atmosphere to the whole painting.

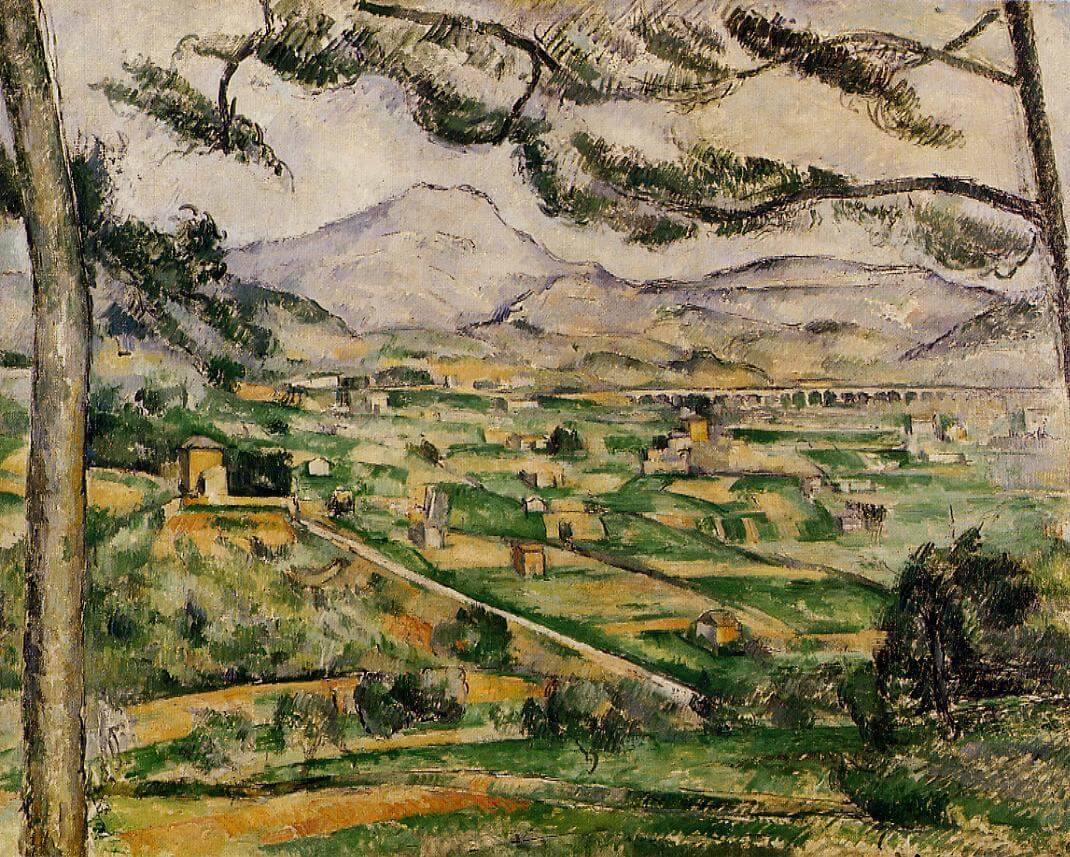

Mount Sainte-Victoire and the Viaduct of the Arc Valley (1882–1885): This work exemplifies the Impressionists' influence on Cézanne's style. The colors are softened, the brush strokes have lost their violence, and the composition invites the viewer into the work. The mountain itself is a backdrop but provides the atmosphere for the whole work. There is a greater feeling of wholeness, and his colors support each other, blending the scene.

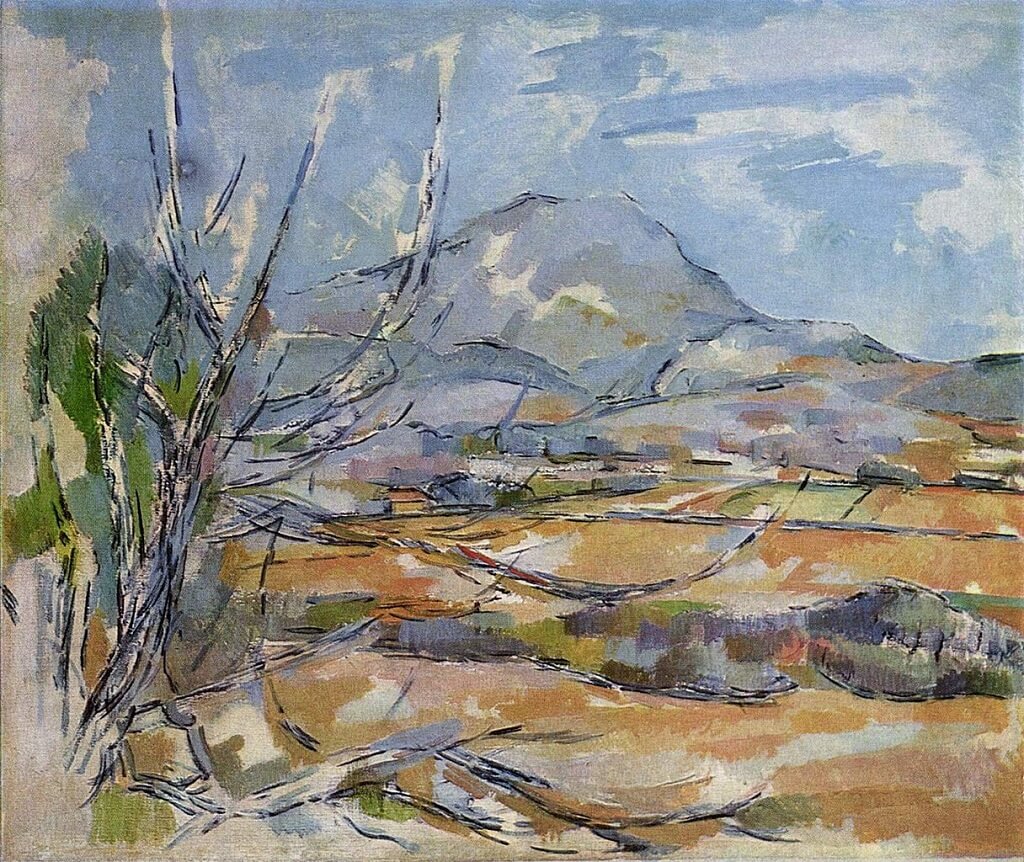

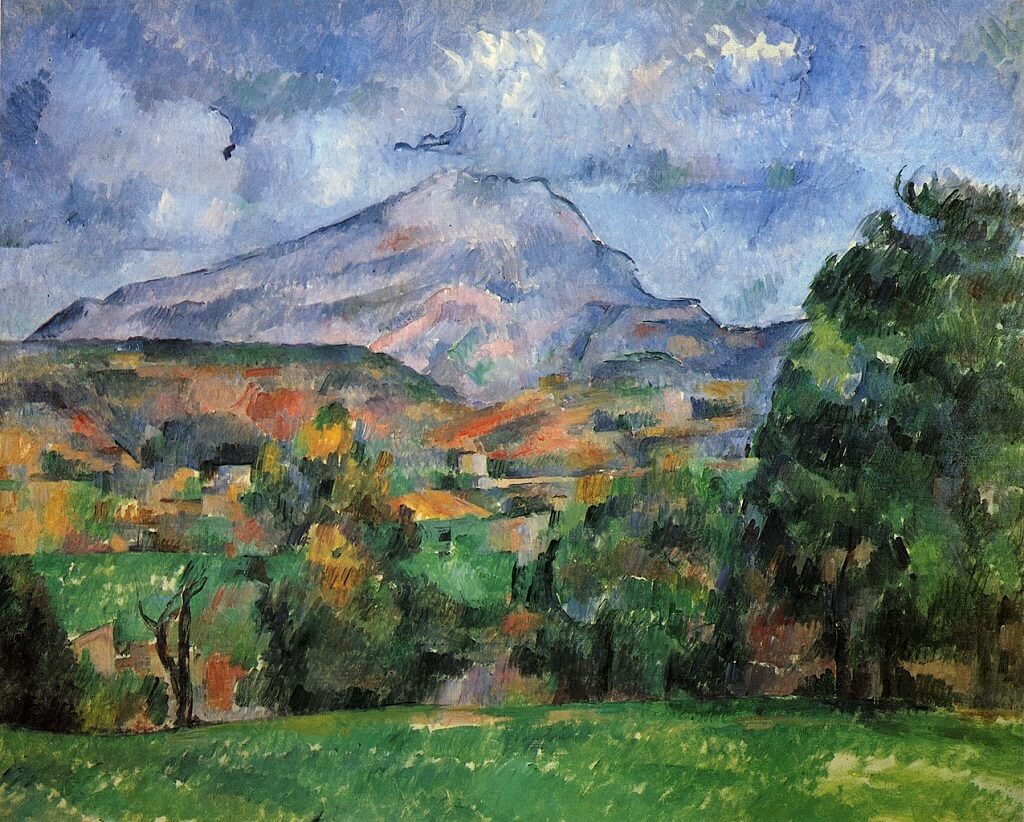

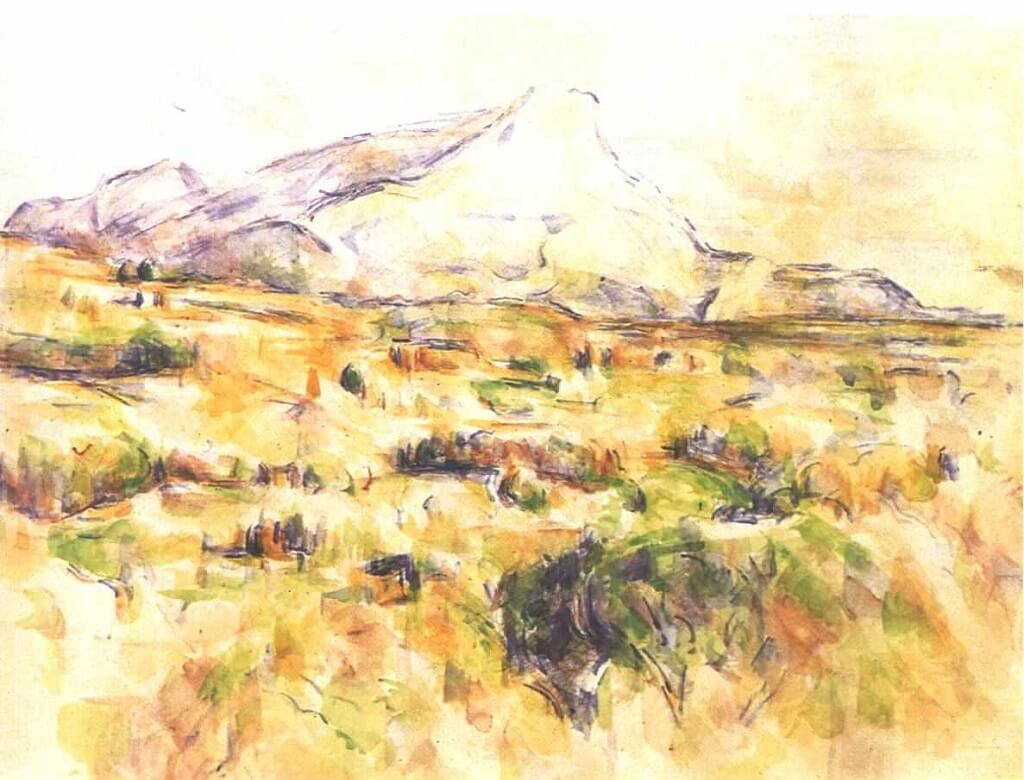

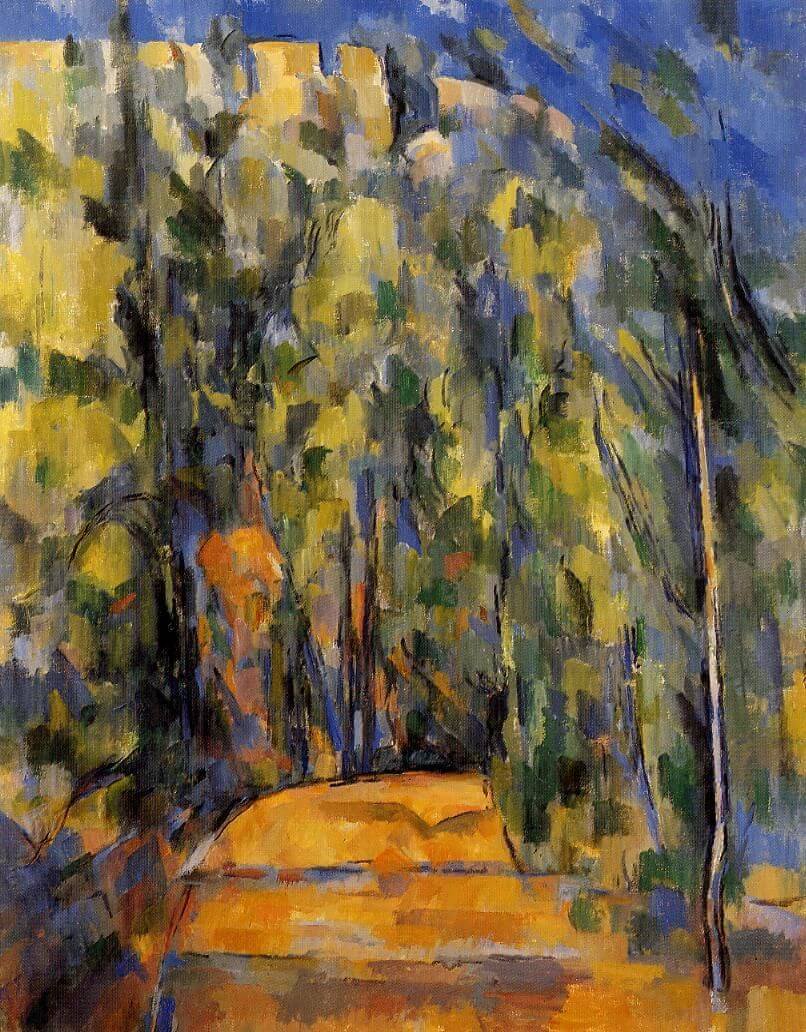

The three versions below were painted in 1887. The first two are oil paintings, and the last one is a watercolor. In these works, the mountain is not the motif yet as it will become in his last years, but some changes in his presentation of the subject are evident. He is looking for the heart of the scene. In the first two, the tree limbs and leaves are guides, as in The Lac d'Annecy (1896), but the emphasis is on the mountain in the third. It is not a backdrop but the object of focus.

As Cézanne became even more obsessed with Mount Sainte-Victoire, he had many conversations with Joachim Gasquet, a young author, poet, and art critic, who was also the son of a friend. Cézanne wrote to him: "There are days when the universe appears to me as a vast flood, a torrent of reflections in the air, reflections that dance all about the ideas of Man." For some reason, Cézanne could express himself easily when he spoke or wrote to Joachim. Again he said, "To paint a landscape properly, I first have to know the geological strata…one fine morning, next day, the geological fundaments are gradually revealed to me, the layers of strata, the great plan of my canvas, and in my mind's eye I trace the skeleton of stone….I start to acquire some detachment from the landscape to see it. This first sketch, these geological lines… they are what releases me from it. Geometry, the yardstick of the Earth.

And again, after the sketch, came color: "At times I conceive of colors as vast, noumenal entities (the world of things outside us, like trees, dogs, houses, things that are real), ideas with a physical presence, creatures of pure reason with whom we can enter into relations. Nature is not an affair of the surface, it is depth. Colors express that depth on the surface. They arise from the roots of the world. They are its life, the life of ideas." Below, Cézanne shows his theories as he is putting them into practice. He is painting the mountain from the inside out and the outside in. The permanence of the structure allows him to expose it as he sees it, and in turn, he interprets the scene for his viewers to enjoy.

Cézanne seems to be painting through glasses with raindrops. The colors bounce off each other.

Cézanne turned more towards watercolors in his last few years to find the freedom of expression he wanted. It was fluid and equally expressive as he let each layer dry between brush strokes to attain the familiar permanence he sought.

Cézanne worked his way toward Cubism, and these paintings inspired the Fauves, the Cubists, and the Abstract artists who followed him as they moved on in the 20th century.

A final comparison between the first painting in these four vignettes and the last from 1906 provides the visuals and shows the journey he made in his career to the Modern era in painting. He was a genius and one that had stayed true to himself.

His life ended abruptly on October 22, 1906, when he died from pneumonia that he had contracted while painting outdoors in the rain. He died just a few days after his last "en plein air" day, at age 67.

Fun fact: Recently, a Mount Sainte-Victoire painting from the Paul Allen collection sold for $137.8 million at auction. It would be fascinating to speak today with Cézanne and Van Gogh (who died in 1890, age 37) as their contemporary public reviled them. Their reactions to the price of their works of art today would be fascinating, and to question both of them as to what they think of the direction art took in the Modern Era, would be illuminating. Conclusion: Looking at Cézanne's landscapes over time, it is possible to see how he revealed his character, feelings, and individuality as he explored every artistic avenue of expression. Separating the body of work of an artist may hide some critical features, but Cézanne remained faithful to his passion whether he was painting a portrait, a still-life, or a landscape. As viewers, we can see and follow, step by careful step, as he changed the face of art.

Written by Carol Morse

References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us