|

Where? Prints are part of the collections of several museum around the world, including the Ashmolean Museum, National Gallery of Art, National Galleries Scotland, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Rijksmuseum.

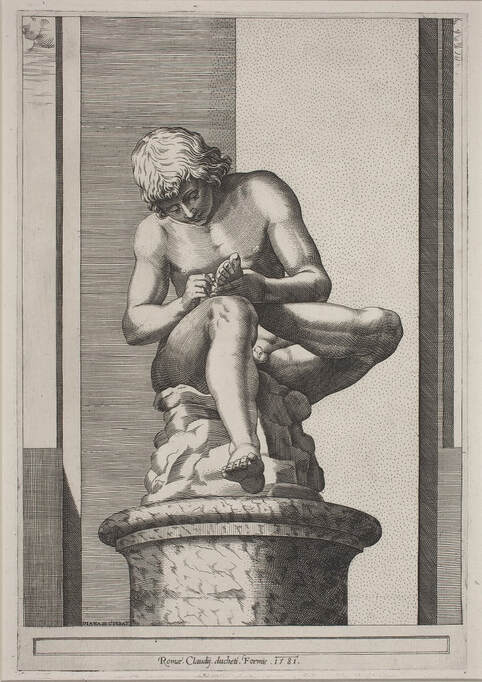

When? 1581 What? Engraving on laid paper: plate: 30.6 x 20.8 cm; sheet: 54.2 x 42.9 cm. What do you see? A young nude boy sits on a pile of rocks, intently focused on removing a thorn from his bare foot. The statue sits in the corner of a room or foyer. Puffy clouds visible in the upper part of the window on the left help to define the available light source. Engraving techniques produce the textures that indicate the depth of the walls and the space the statue occupies. Each shadow is created by a multitude of fine lines, overlapping lines, and cross-hatching. The marble pedestal supporting the statue raises the young boy so the viewer can see the scene from below. His right foot does not touch the ground or rest as he tries to remove this thorn without inflicting more pain. The story and original sculpture date back to a Classical Roman marble that is said to be a copy of an even earlier Grecian bronze rendition lost in the 3rd century B.C. Reproductions of the statue were one of Rome's most widely admired antiquities, and drawings and prints were popular and in demand. A copy of the original ancient statue can be found at Palazzo dei Conservatori, which is part of the Capitoline Museums in Rome. It is recorded as having been there since 1499-1500.

Backstory: A story attached to the sculpture suggests the young boy was a slave, and perhaps he stepped on the thorn while treading grapes in the wine harvest. The alternate name for the statue and engraving is "Il Fedele" (The Faithful Boy). This legend involves a shepherd boy who delivered an important message to the Roman Senate and ran without stopping to complete his task before removing the thorn.

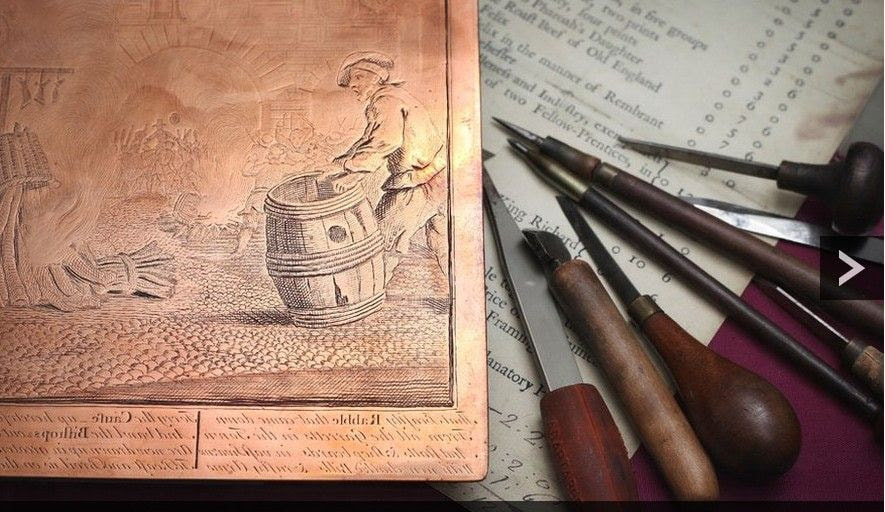

Engraving Technique: The original drawing would have been transferred to a metal plate, typically copper, using a burin. This tool is a small, metal rod with a pointed, triangular head. A cut is made beneath the surface of the metal, and the resulting burr, which develops as the plate is cut, is removed, so each line is sharply defined. The edges of the burrs can be polished for even more precision in the final print. Ink is spread over the plate but wiped off the surface, so it only remains in the cuts. Paper (dampened) is firmly pressed against the plate and forced into the design. The ink image appears. It is a complicated and delicate process that requires great skill.

The Spinario is dated 1581, seven years before Scultori's final published engraving. It is one of her less complicated projects but demonstrates the sophisticated techniques required to produce a print. The engraving was based on an unidentified drawing of a copy of the sculpture. No evidence of the person who commissioned the work has been found. It may have been produced and published to sell as one of the popular stories of the time. These small works provided regular employment and constant income for the artist, the engraver, and the publisher. Diana's name is engraved at the bottom left of the print, and at the bottom is the name of the publisher (Claudio Duchetti), the date of the production (1581), and the city (Rome). Duchetti was a print dealer and publisher born in France but active in Italy, first in Venice, then in Rome. He and his uncle, Antonio Lafreri (1512-1577), had business associations with Diana and her elder brother, Adamo Scultori (1530-1585).

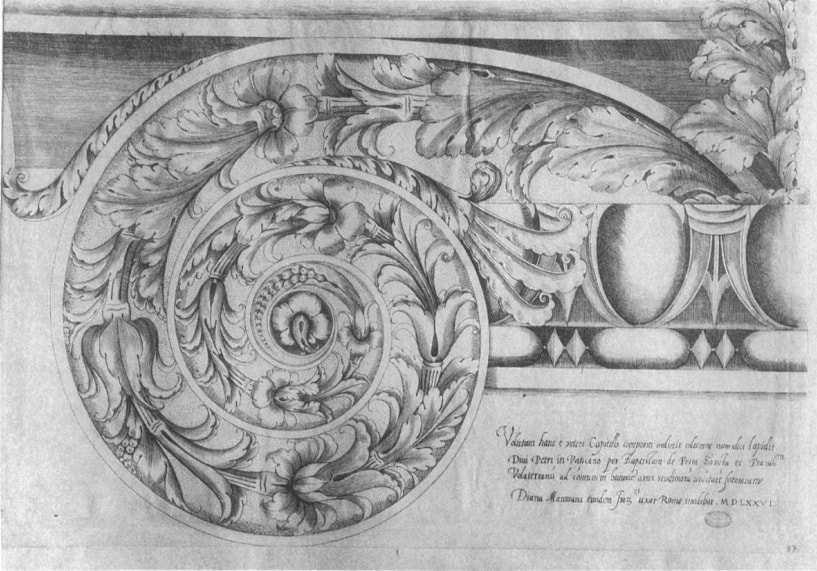

Who was Scultori? Diana Scultori was an engraver of mythological and religious subjects. She was born in Mantua in 1547 and died in Rome, 65 years later. Her father, Giovanni Battista Scultori (1503-1575), was an artist, engraver, and sculptor who served the Mantuan Court of the Gonzaga family. He made drawings for and worked in the 1520s with Giulio Romano (1499-1546), a Mannerist painter, architect, and former pupil of Raphael. His access to Romano's art allowed him and his children to reproduce these popular engravings and to establish their reputations in the art of reproductions. Diana was seventeen years younger than her brother. Their father taught both the art of engraving. It was customary for a son to follow in his father's footsteps, but for a woman to be trained in engraving was very unusual. Giovanni, however, saw no reason to teach Diana to draw, which left her dependent on the work of others throughout her career and limited her creativity to copy work. The Importance of a Name: Diana Scultori belongs to the few Renaissance women who managed to carve careers and reputations for themselves in the contemporary art world. She was the first woman to sign her name on her prints and used several names to identify herself: Diana Mantuana, Diana Mantuvana, or Diana. In 1579, she and her husband were made citizens of Volterra, and she added Diana, Civis Volaterana. The name Ghisi is often attached in error to both herself, her brother, and her father. This was the last name of a close childhood friend who was a pupil of Giovanni but not related. She never used her father's last name as it would have indicated she was a sculptor, and the name, Scultori, was assigned to her years after her death. Instead, the names she used became a marketing tool to promote her work and that of her husband. In this, she was unique. In 1566, when she was 19, Giorgio Vasari met her in Mantua. His comment was recorded: "but more marvelous, a daughter named Diana also engraves so well that it is a wonderful thing, and when I saw her a very well-bred and charming young lady and her works, which are most beautiful, I was stunned." In 1568, he mentioned her in the second edition of his book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. This is the first published notice of her work, and his approval gave further impetus to her prestige and career. Time in Rome: Diana Scultori met and married Francesco Capriani of Volterra, in Mantua. He was an architect who had been hired by one of the Gonzagas to come to Mantua in 1565. Sometime between 1570 and 1575, the couple moved to Rome. Francesco was to work for one of the papal Cardinals. Their new home was a gift as long as Francesco redesigned and renovated their house and one other in the area. These renovations also gave them a chance to advertise Francesco's architectural business. They lived in the Campo Marzio region, the traditional neighborhood for artists, and provided a home for Diana's widowed mother and unwed sister. Adamo had moved to Rome in 1566, and he had contacts with the dealer and publishing house, run by Antonio Lafreri. These ongoing family relationships and business connections from Mantua to the Papal court helped Diana and her husband establish themselves quickly in Rome. She applied for and received a Papal privilege that allowed her to make, sign with her name, and market her own artwork (June 5th, 1575). She was the first woman to obtain this privilege. The license also specified that nobody could reproduce her work on the pain of a hefty fine and immediate ex-communication. She had no such restrictions placed on her regarding the use of other peoples' engravings. This meant that she was free to use her printmaking to help secure commissions for her husband's architectural business and proceed with her career. Diana and Francesco worked as a team, perhaps the first "power couple" outside of the nobility in history. Francesco produced his architectural drawings, Diana reproduced them for distribution to the elite, the Papal court, or to be sold through a publisher/dealer. She often added lengthy inscriptions that explained the work of art and allowed both their names to be seen, recognized, and referred to others. Dedications inscribed to their clients on the reproductions brought fame and fortune to themselves and added stature to their patrons' reputations. Many other of her reproductions were small devotional pieces that provided financial support for the family.

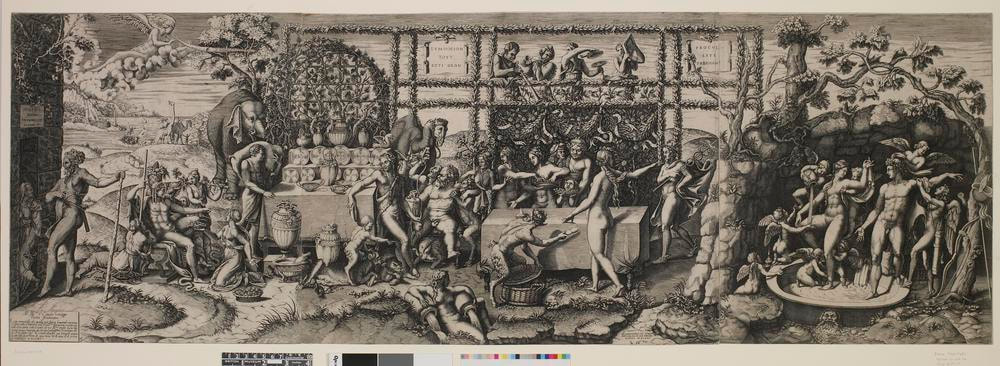

This is one of Diana's more challenging engravings and represents the Mannerist style popular during the 16th century. There is a focus on the human form with complex compositions that contain several densely populated scenes. Design and technique were demanding for all those involved in producing these engravings, from the artist to the engraver to the printer. Her husband, family, and friends all profited from her ability to make and sell her reproductions, and her astute marketing decisions brought new clients for all concerned. Diana never stepped out of the boundaries that surrounded women of the 16th century. Her husband was the primary wage-earner, and her job was to establish a proper, respected household in Rome. She did that, but in the process, she helped pave the way for women in the future to find possibilities for independence through their own art. In particular, Lavinia Fontana used one of her prints as the basis of one of her paintings.

Both Diana and her husband became members of the Confraternity of San Giuseppi, but as a woman, Diana could only attend religious services and help with the dowering of young girls. Francesco, on the other hand, became fully involved with the fraternity for over ten years. This group would have also been important to the establishment of their social position in Rome. In 1578, when Diana was 31, they had their first and only child, a son, Giovanni Battista Capriani. Durante Alberti (1538-1613), The Renaissance painter, was the child's godfather and confirms the social progress they had made in a short time. Her last known print, The Entombment, after Paris Nogari, is from 1588. (Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest)

Fun fact: The importance of Scultori's signature has convinced art historians that she probably did not produce anything after that date. Her husband died in 1594, and she married Giulio Pelosi in 1596, another architect, who was 20 years her junior. There is no evidence of her work after this marriage other than her death in Rome in 1612.

Diana was conservative and conventional in her life, but without arousing suspicion or antagonism, she broke many boundaries imposed on females. She was a businesswoman, an artisan, and a true Renaissance Woman.

Written by Carol Morse

References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us