|

Where? Room 90 of the Uffizi Museum

When? c. 1620 Commissioned by? Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo ll De’ Medici. The Grand Duke died in 1621, shortly after the painting was completed. It was only with the help of Artemisia’s friend, Galileo Galilei, that she managed to extract the payment for the agreed sum for the canvas. Medium and Size: Oil on canvas, 146.5 x 108.0 cm. What do you see? The moment that Judith, with the help of her maidservant Abra, is beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes. Unlike many other artists, Artemisia Gentileschi chose to portray the scene at its zenith. It is the most powerful and horrific moment to imagine. Holofernes still struggles, his right hand fruitlessly trying to jab at Abra. His soon-to-be lifeless forearm comes to rest in the crook of her shoulder. His right knee is bent in a futile attempt to escape. Abra’s arms press downwards with great strain to hold Holofernes’ left arm down and still. The concentration and intense focus on what she is doing registers in her facial expression. Abra’s hair is covered with a white turban, and she wears a blue dress. The white sheet and the red coverlet lay rumpled over the commander. The sword's thrust in Judith’s hand produces blood spurts that reach Abra’s arm and Judith’s dress and body. Blood seeps over the bed and down the edges as life drains from him. His face is already losing the expression that gives it life, and it will soon be tucked into the food bag, wrapped in the bejeweled cloth that will be triumphantly removed once the two Jewish women return to their hometown Bethulia. Judith strains! The force she is expending is visible as she clutches the hair on Holofernes head and presses his head into the mattress with her left arm. Her right arm twists and rotates as the sword makes its cut. She uses the sword of Holofernes. The edge of the cross on the sword digs into the skin of his upper left arm, and we can see the pressure on it. Sleeves rolled up on both the women suggest they had some time to prepare, at least a bit, beforehand. He must have been quite drunk. The gown that Judith is wearing attests to the seduction that was her purpose. The low cut of the dress exposes her breasts and must have been enticing to Holofernes. Her hair is coiffed in the style of a noblewoman, uncovered, revealing its charms. She apparently was perfumed and prepared to seduce. Artemisia has painted one of her own bracelets on Judith’s arm in this second version of the scene. One cameo depicts Artemis, the ancient goddess of chastity and the hunt. It raises the question of whether Artemisia identified with this goddess? The textured walls of the tent provide a dark backdrop that not only frames the scene but also produces the contrast between light and dark that intensifies the actions of each individual. The light source comes from the left. The composition of the three figures focuses the viewer’s attention on the central part of the canvas.

The colors in this painting: The colors used have a symbolic meaning, and people would have recognized their significance in Christian art. Double meanings do leave room for various interpretations. The gold of Judith’s dress most likely stands for glory, although divinity or truth are applicable. Its opposite is cowardice, yellow, often used when depicting Judas but unlikely in this case. Red stands for love or sin, heat, passion but also suffering, and perhaps the coverlet refers to the suffering of Judith’s unwanted but necessary seduction. The blue of Abra’s gown might reflect the constancy or fidelity of the handmaid in her service to Judith. The black of the background suggests evil or death, and the sword of Holofernes used on himself may refer to life, death, or salvation. The prominence of the cross on the sword in Judith’s hand more likely indicates the latter but for Judith, not Holofernes.

Judith in art history: According to the Khan Academy, Judith has been a popular subject throughout art history, but ever-changing in appearance and motivation according to societal and artistic trends. In the Middle Ages, she was presented as a virtuous woman, akin to the Virgin Mary. By the early Renaissance, she became more political; Judith as a warrior striking down the tyrant, like in the sculpture by Donatello in the Palazzo Vecchio. Later Renaissance artists portrayed Judith as more seductive and aggressive. The Northern Renaissance artists presented her in nude forms, and during Artemisia’s era, the Baroque, it became an opportunity to indulge in gore. Judith became the violent assassin expressing “female rage.” Possibly for Artemisia, the rage against her rape provided her with an artistic vent against her inability to protect or defend herself in such a male-dominated world. Finally, during the Belle Epoque, Judith can be seen as the Femme Fatale, Holofernes, almost appearing as an after-thought, as seen in Gustav Klimt’s version.

Biblical Story: The original biblical story is found in the Book of Judith: It is believed to have been written in the late 2nd or early 1st century, B.C. “As commander-in-chief of the Assyrian troops, Holofernes is instructed by the Assyrian king, Nebuchadnezzar, to conquer the people in the West.

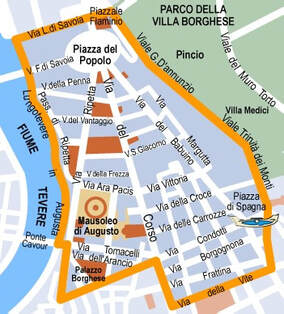

The enemy camp is established outside the Jewish town of Bethulia. The name of the town refers to Beth-el and means “the house of God.”It is located somewhere in Palestine, perhaps the Samarian hills, and although it has been placed in geographical regions, it may be fictional. The town was besieged with the water supply cut off, and the townspeople wanted to surrender to Holofernes to save themselves. The story revolves around Judith, a daring and beautiful widow, upset with her Jewish countrymen for not trusting God to deliver them from their foreign conquerors. She goes with her maid, Abra, to the camp of the enemy and slowly ingratiates herself with Holofernes. She promises him information on the Israelites. By gaining his trust, she is allowed access to his tent one night as he lies in a drunken stupor. She decapitates him, then takes his head back to her fearful countrymen. The Assyrians, having lost their leader, disperse and Israel is saved. It is the classic tale of good over evil, inferior against superior, heroine versus villain. Judith risks it all to be the savior of her people. Who was Artemisia Gentileschi? She was born in 1593 in Rome. Artemisia was to become one of the most well-known female artists in her contemporary world and is recognized today as a master artist. Artemisia was raped when she was 17, and her early artistic accomplishments are inextricably related to the rape and trial that followed. Though she was a victim, it can never be said that she was victimized. She endured and used all her strength, her artistic skills, and her emotions to portray the power of strong women in many of her narrative paintings for the rest of her life. She vehemently lived her life on her terms and by the 20th century had become a beacon for feminism. She personified the Baroque style following Caravaggio, portraying realistic scenes, natural settings, and brilliant use of color. Because she had been admitted to the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence, she was allowed to paint nude female models, which was unheard of for most women artists at the time. Her travels took her through Italy and eventually to England to help her father with his last commission for King Charles I and his wife, Queen Henrietta Maria. She returned to Naples and most likely died in the mid 1560s during the plague. What world was she born into? It was one where arranged marriage for women was the norm. Negotiations concerned the property that a woman could bring to the union, be it a cow or horse or a house or a farm. Was she of good stock and character? The nobility and ruling classes married women off for the political gains that could be had or perhaps, even for a country. Women were mere chattel, meant to become housewives or sent off to a nunnery if they could not find a husband. They were owned by their fathers and brothers and then by their husbands and considered fit only for “women’s work.” There were exceptions to the rule, but any power they had was still subject to males' approval. Society was organized with international banking and trading systems, and the government was organized at the state and city levels with powerful church input. The reformation and the counter-reformation continued into the mid-1600s. The Sack of Rome in 1527 had enormous effects on the economics and politics of all of Europe. “Rome itself was in ruins, depleted, in every way. The population had decreased from over 50,000 to 10,000 inhabitants, and the abandoned city was austere, had become anti-Humanist and anti-artistic. It wasn’t until Sixtus V's papacy (1585-1590) that Rome began to recover. It is hard to imagine that just years before 1527, Rome had been the leader of the High Renaissance. However, Sixtus set about repairing and improving the aqueducts, bringing water to the whole city. Broad avenues were constructed to connect the major churches and provide access for the pilgrims who came to see St Peter’s and all the other pilgrimage churches. The Catholic Church was ready to demonstrate the grandeur of the revitalized capital of Western Christianity by building and decorating new churches and palaces, and the patronage of popes and their aristocratic families flowed freely. It was an attempt to re-solidify their power against the forces of Protestantism. In the service of these objectives, a new style in art and decoration developed and became popular. It is known as Baroque.” (The History of European Art, The Great Course, Professor William Kloss) Other active painters during this time? In Italy, there was Tintoretto, Caravaggio, Carracci and Bernini to name a few. El Greco was born in Greece but spent most of his life painting in Spain, as did Velázquez. The Flemish artists Jan Brueghel the Elder and Rubens often collaborated on projects, and Rembrandt, Frans Hals, and Vermeer were part of the Dutch Golden Age of Art. These were just some of the artists affecting the styles and changes in the art world, and it was into this world that Artemisia Gentileschi was born July 8, 1593, in Rome. She was about to break the mold. The family of Artemisia Gentileschi: Artemisia came from a well-known family. Her father was a respected painter, born in Tuscany but working in Rome in his twenties. He painted in the Mannerist style, characterized by vivid, often harsh colors, dramatic subject matter, and elongated or exaggerated figures. Madonna’s with very long, elongated necks were popular in this period. Orazio often worked in collaboration with other artists, providing figures for their work. One artist, Agostino Tassi, would play a terrible role in Artemisia’s young life. Artemisia’s mother, Prudenzia di Ottaviano Montoni, and father lived in the rione of Campo Marzio. (It was in this Campo, not far from where Orazio and his family lived, that Caravaggio would murder an officer in a duel leading to a death sentence in 1606.) Elizabeth S. Cohen provides an animated description of the area, which played such a role in Artemisia’s life. It was heterogeneous, mobile, violent with a motley group of occupations and nationalities. There were monks, river men to grandees and grooms, artists both temporary and long-term. By papal regulation, the city’s prostitutes lived in this area too. There were many restless young men in search of company, sex, or a brawl. The neighborhood was full of animation and mayhem. The family lived in this area but moved several times in Artemisia’s childhood. She was born on Via Ripetta and lived there for the first eight years of her life. In 1601 they moved to Via Babuino, where her mother would die in 1605. In 1610 they moved to Via Margutta, and it was in this house that Agostino Tassi raped her. They moved again in 1612 to Via della Croce and must have been here during the rape trial. Her mother’s death in 1605 was a tragedy that the whole family had to endure. At this point, Artemisia was the eldest child, and with three younger brothers, much responsibility must have fallen on her shoulders. By then, her father was in a quandary as to how to raise not only boys by himself but a daughter that he would have to find a husband for or else send off to a nunnery. The map indicates the neighborhood they lived in. It was noisy, busy, quite near the Spanish steps and many other pilgrim churches and places of interest were near-by. Today, it remains one of the most active areas of Rome.

More about Artemisia Gentileschi: Her neighborhood was her world for most of her childhood. Girls would have been more protected than boys, but daily chores were probably done with her mother. Her father knew both Caravaggio (the Baroque artist) and Agostino Tassi (a painter of frescoes in Rome) by the time she was born. Orazio was about 15 years older than Tassi and about eight years older than Caravaggio. Caravaggio was always known for his violent, rabble-rousing, aggressive behavior, and Tassi was certainly no angel. Orazio fell in with them easily, so he must have also been a bit of a rough and tumble sort.

Orazio was 30 when Artemisia was born in 1593. He trained his children in his studio, exposing them to the comings and goings of artists, models, friends, and the works their father produced. The neighborhood people would have been models, and nude bodies in the studio would not have been unusual. The prostitutes in the area were the ones most likely to be willing to remove their clothes and pose for the artists who lived there. By 1600, Orazio was heavily influenced by Caravaggio’s work and adapted his Mannerist style to produce more Baroque works. His career would be at its height in the next ten years. Orazio, Caravaggio, and two others got themselves into trouble in August 1603. Giovanni Baglione filed a suit for libel connected with some unflattering poems circulated amongst Rome's artistic community over the preceding summer. This suit was just three years before Caravaggio was convicted of murder. It is most likely that Artemisia had met Caravaggio and Tassi as a child. She was influenced both by the work of her father and Caravaggio. Artemisia was twelve when her mother died in 1605. Historians believe that she was learning how to grind and mix paint, wrap brushes, drawing, and paint under her father’s guidance in the following years. She proved to be more talented than her brothers, and by the time she was 15, Orazio was more than aware of her artistic skills. He bragged about her. First works by Gentileschi: Mary Garrard, an Artemisia specialist, believes her earliest known painting, based on her father’s Madonna, is Madonna and Child. She thinks it was painted in 1609, not 1613, as stated by some experts. Both works use more naturalistic figures than Caravaggio promoted. They used the chiaroscuro technique typical of the Baroque era. The dark creates the atmosphere of the painting and becomes as important as the composition and the figures.

It is more widely accepted that Artemisia’s first-known work is Susanna and the Elders, which she created in 1610. She paints the tale of a virtuous young wife at the baths being sexually harassed by the community's elders. She painted Susanna’s fearful rejection of their advances and intimidation.

This painting was done when Artemisia was 17 years old. She already expresses anatomy in a bold, natural manner suggesting that many drawings, observations, and study of flesh colors preceded this work. The composition is arresting, with a triangle guiding viewers from face to face. Susanna’s distress is powerful. Artemisia’s sensitivity, artistic skill, and knowledge are apparent. Biblical tales were popular, and her gravitation to these stories indicates that she also understood that she had to paint what would sell.

Rape: In early May 1611, a life-changing event occurred. Her father had been working with Tassi once again. It isn’t clear whether Orazio had employed him to help Artemisia with her art or whether he just was around the studio as a visitor. Orazio had hired a woman to chaperone Artemisia, but she had disappeared somewhere. And while Artemisia was in the studio painting, Agostino Tassi entered, forced her down a hallway into a bedroom, and raped her. A promise of marriage followed, and sexual relations between Tassi and Artemisia were allowed to continue. This was a common solution to rape at the time. About 8 or 9 months later, following a financial dispute between Orazio and Tassi, the offer of marriage was retracted. Orazio then filed charges with the court accusing Tassi of “deflowering” his daughter. A very public, humiliating trial took place. It was recorded and stored in the Rome State Archives. Artemisia was 17, and Tassi was a 33-year-old man. She testified to having fought him, scratching and punching, but eventually, he had overpowered her. She threw a knife at him following the rape but missed, which seemed to amuse him rather than scare him off. The trial was horrendous. Not only did she have to recount the story to the court, but she was also subjected to a virginity test. (One wonders why as sexual relations had been allowed to continue between the two.) She was then tortured by the “sabille,” a technique using ropes tied around her fingers and then tightened. This torture was to test her story's veracity and her denials regarding the accusations Tassi made against her. He accused her of being a whore, unstable and untrustworthy. Tassi was allowed to question her himself and all of this done in public. While Tassi was held in jail, she was taken to his cell, where she was asked to repeat her claim of rape to his face. It was found during the trial that Tassi already had a wife, whom he had tried to have killed. He had also engaged in illegal sexual relations with his sister-in-law and had planned to steal some of Orazio’s paintings. The trial lasted seven months. Tassi was found guilty and given a choice of exile from Rome or prison. He chose prison, but the sentence was never carried out. He had some very powerful friends who came to his aid. It was Artemisia who left her home. A quickly arranged marriage to the brother of the solicitor who had represented Orazio took place in November of 1612, just days following the trial. He was a minor painter from Florence named Pietro Antonio Stiasetti. In December, the couple made plans to move to Florence. Most women in this situation at that time would have disappeared into the fog of history. Artemisia did not. By March of 1613, she had a studio set up in her father-in-law’s home. She and her husband had five children, but only a daughter, Prudenzia, named for Artemisia’s mother, survived. One son, Cristofano, lived for four and a half years. His death was devastating for Artemisia. Affair: This was not a happy marriage, and by 1618, she had embarked on an affair with Francesco Maria Maringhi. He was a well-connected business associate of her husband. Letters were discovered in 2011 written by Artemisia and her husband to her Florentine lover. Most were exchanged after their departure from Florence. The National Gallery has a discussion of the letters. “They offer a glimpse into Artemisia’s most intimate thoughts and feelings. She didn’t learn to read or write until she moved to Florence and the grammatical mistakes and phonetic spellings in her writing merely add to the strong character that emerges from these letters. She directs her passion not only at Maringhi: she communicates with equal fervor about the urgent return of her belongings, the recent death of her four and one-half-year old son and both her jealousy and yearning for her distant lover. Her personality comes sharply into focus, forcing us to adjust any ideas that she was a victim. Instead, a witty, passionate woman emerges, determined to control her own destiny and gain the respect she deserves. Her letters reveal that she was much more cultured than previously thought and her fiery personality and vulnerability also come through in the letters.” Her time in Florence was a good thing for her career, if not her personal life. She and her husband lived there from 1612 to 1620, when they returned to Via della Croce in Rome. In these eight years in Florence, Artemisia became a successful court painter, enjoying the patronage of the House of Medici. She was the first woman to be accepted into the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in 2016. Here she met most of the respected artists of Florence and was introduced to the academic world. She gained the patronage and protection of many influential people. Her exposure to courtly culture and fashion helped her to depict the lavish clothing in her paintings. “Artemisia understood that the representation of biblical or mythological figures in contemporary dress was an essential feature of the spectacle of courtly life.” It was popular, and it sold. Two versions: Gentileschi painted two versions of Judith Beheading Holofernes. The first version was painted in 1612-1613, just following her rape and the trial. She was approximately 20 years old. There is no clear indication that it was commissioned, and she may have painted it in Rome before her marriage. It was not documented until 1827, when it was found in a collection in Naples. It is on display in the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples. The 1620-21 version in the Uffizi Museum may have been started in Florence but was finished in Rome and delivered back to The Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo II. In the 1800’s it was so disliked that it was hidden in the back in the dark of the gallery. In both paintings, the portrayal of Judith is seen as a self-portrait of Artemisia.

Both paintings are grand, sensuous, and dramatic. The viewer experiences the movement, tension, and emotion of the moment. Baroque art was meant to extend the public’s faith in the Catholic Church following the rise of Protestantism, so the spiritual side was part of its appeal. But the naturalness, the reality had to be seen. The narrative had to be obvious. Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro is demonstrated, and Artemisia used this to great effect in many of her history paintings. The dark emphasizes the light source to bring the figures to maximum attention. The second version is more successful because of her improved use of the technique. The earlier work was painted in the immediate aftermath of the rape and trial. The deeper primary colors are more subdued. Judith wears a cobalt blue dress, and Abra is in deep red. The second version is much more refined. She has attended the Academy of the Arts and Drawing in Florence, and she displays her new skills with changes to the composition that increase interest in the painting.

She has also had more time to absorb what happened to her and is more sensitive and objective in presenting the work's emotional aspect. Her female figures are smaller but seem closer to the viewer. They work together in tandem. She has altered Judith’s hair to the more contemporary curls and braids in the style of a noble Florentine woman, mimicking the Classicism inherent in the Baroque period. The fabrics in the dresses are richer in color with greater drapery folds. Even the turban wrapped around Abra’s head brings extra drama to the scene. The bracelet, missing in the first version, adds a personal touch, and Artemisia’s identification with Judith is evident. She added this cameo adornment with the Goddess Artemis, patron of girls and young women and a protectress during childbirth, featured boldly in the golden links. When she painted this version, she had not only suffered through the rape and trial, but she had had five children, with only one daughter who survived. Drawing further attention to the bracelet is the pattern of blood spatters. Artemisia must have been familiar with Galileo’s research on parabolic trajectories. He was her friend in Florence, and the altered blood spurts in this second version are much more realistic and may have been a result of that knowledge. The drops of blood that follow the arc of the bracelet give even more importance to it.

Artemisia went on following her return to Rome to forge a life for herself. Her husband seems to have disappeared from her life by 1624. She found many patrons for her work but was largely excluded from papal commissions, probably both because she was a woman and her skills with large-scale works were doubted. She wrote with anger that after sending her drawings to one of her patrons, he used her work to have another artist paint the subject! She said never again would she be so used!! In 1627, when she was 34, she moved to Venice, and in 1630, fleeing the plague, she moved to Naples, which was under Spanish rule. In 1638 she joined her father in London to assist him with his royal commissions. After her father died in 1639, she remained in England for a brief period and then returned to Naples for the rest of her life. History has attempted to define this woman by her rape, but she herself did not. Her early upbringing, circumstances, and experience taught her independence, and her fiery personality enabled her to fight for herself in a world that rejected the worth of women. She painted bold, strong females, and she fought for recognition, respect for her art and herself. In her contemporary world, she was successful! She belonged to the circle of the best painters of her time. Nowadays, she has become an icon and recognized as one of the great masters of painting. Curious Questions about Artemisia’s models: Artemisia painted another very violent biblical scene, Jael and Sisera. He was a Canaanite leader who sought refuge in her tent. She agreed and then killed him in his sleep by driving a tent peg through his temple. This was painted around 1620, close to the time she painted her second version of Judith. Some sources suggest that the male model for this painting was Caravaggio. But why would Artemisia want to pound a peg through his temple? She knew him as a child, and Caravaggio’s art style heavily inspired her.

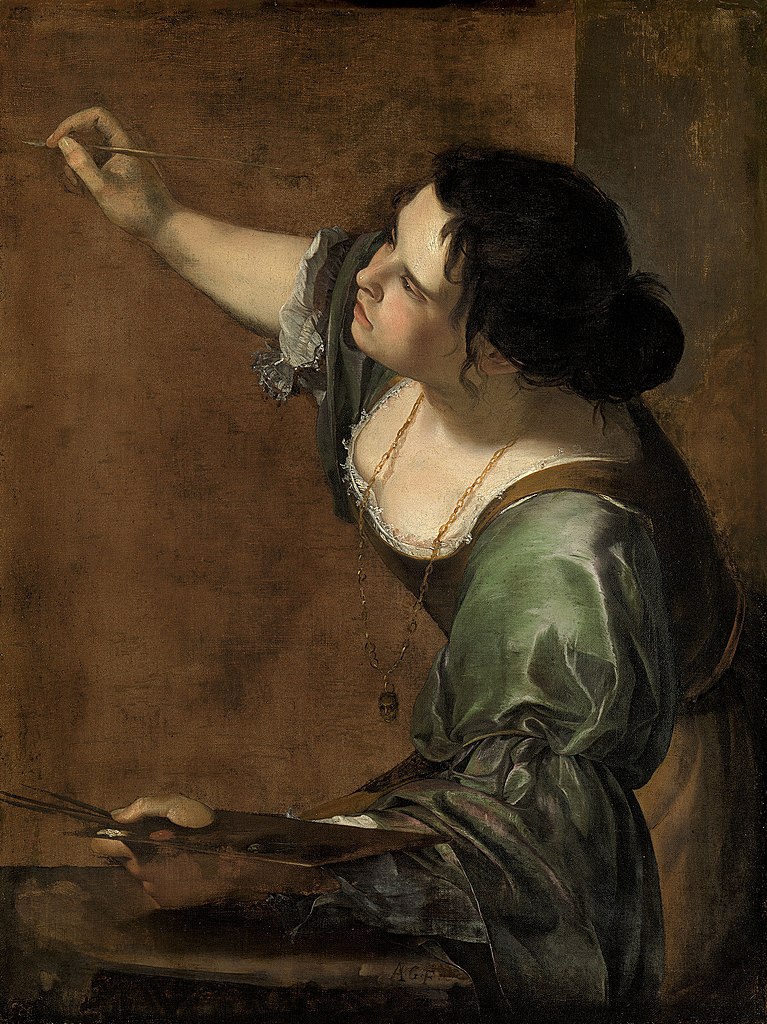

Artemisia in her own paintings:

We see Artemisia’s face in many of her history paintings, particularly one that was in the National Gallery exhibition 2020-2021: Self Portrait as St. Catherine of Alexandria. This painting has recently been cleaned and restored. She again represents herself as one of history’s female martyrs, and the symbols she uses relate to the suffering of so many women including herself.

She painted this in London when she was forty-five. Again, Artemisia is making an enormous statement as she represents herself as the epitome of the idea of art.

Mary Garrard writes in her analysis of the painting: The fact is, no man could have painted this particular image because by tradition the art of painting was symbolized by an allegorical female figure, and thus only a woman could identify herself with the personification. By joining the types of the artist portrait and the allegory of painting, Gentileschi managed to unite in a single image two themes that male artists had been obliged to treat separately, even though these themes often carried the same basic message. (Her complete analysis can be found on-line.) By representing herself in the act of painting, her chin jutting forward, palette ready, she is declaring, in this mans world, that she is achieving, fulfilling her goal and finding satisfaction by herself…..a very radical statement in those days. Even the pendant with a mask has a message—it represents the imitation she creates of life. Her life was indeed a journey and she was one of the first women to live it, in many ways, on her own terms. It is believed that her lover, Francesco Maria Maringhi remained part of her life for many years but it is known that she did have other lovers. Her daughter became an artist, likely taught by her own mother. Her patrons included Kings, Queens, and the aristocracy in Florence, Rome, Venice, Naples and London. She finally managed to obtain a commission for an altarpiece in a church in Naples, but not until the 1630’s. She joined her father in London in 1638 to help him with the work he was doing for Charles I. Her father died in 1639, while they were in London and Artemisia returned to Naples sometime before the English Civil War. (by 1642) Artemisia was probably swept away in the plague that hit Naples in 1656 but there is no certainly as to how she died. Her paintings are full of narrative and well worth the effort of understanding each one on their own. Written by: Carol Morse Bibliography:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us