|

Where? The Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham, England.

When? About 1800 Commissioned by? Most likely painted for the Golovine family. The painting remained in their possession until approximately 1978, when it was acquired by Gooden and Fox, then it was sold to the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in 1980. What? Oil on canvas, octagonal, 32 7/8 by 26 1/4 inches (83.5 by 66.7 cm.) What do you see? No matter what room this portrait of Countess Barbara Nicolaievna Golovine is in, it will be the first painting to demand attention. The innovative composition is a half-length figure in an octagonal shape and is further enhanced by an attractive gold frame. Vigée Le Brun has wrapped her subject entirely in a large, thick, rich, red stole with gold embroidered trim. The luxurious wrap is draped carefully but casually, and held gracefully at her neck by one hand, as if she has just come from her boudoir or the bath. The red shawl commands immediate attention. Her loose and free, brown, curling hair tumbles around her face and shoulder, held in place by a deep golden headband that has a twist and texture that adds to the framing of her face. There is a dimple in her chin that augments the slight smile on her face and blends gracefully with the shadows of the light and dark. In fact, the dimple makes her face much more interesting. The neutral, scumbled background has a diagonal shaft of light cutting across the canvas that adds clarity to her hand and facial features. It is an unusual backdrop that suits the countess’s dynamic pose. She faces us, while her body turns slightly to the left, suggesting motion. There is an erotic hint to the painting but that is over-whelmed by the soft smile and the warmth of her eyes as she engages the viewer. She is pleased to see her visitor, a friend, a well-liked friend, who will be welcomed and entertained with excellent conversation, perhaps a glass of French wine, for she was a member of the Russian Aristocracy, a Princess first, then a Countess, when friendships, manners and virtue mattered more than anything. As the viewer turns away, moving either to the left or right, a glance over a shoulder confirms that her eyes are following as she bids her farewell……it is not a portrait easily forgotten by anyone who views it, and one that many, return to view again and again.

Backstory: This compelling portrait is an invitation to see and understand not only the two women involved with this specific portrait but also the workings of 18th century aristocracy. Countess Golovine spent the early part of her life in the Russian Court of Catherine The Great (Catherine II). Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun was painter to the French Court of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Both sitter and painter wrote their memoirs, one called “Recollections” and the other “Souvenirs”. The memoirs afford us a rich and deep look at the aristocracy involved in both Russian and French Courts. They are both open and honest about their lives and their writings reflect the upheavals of political and social life in the latter half of the 18th Century.

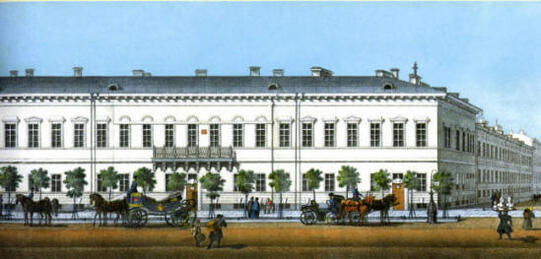

The stories of their daily lives and the intrigues and adventures they were part of or witnessed provide not only historical information, but visuals of what life was like for the very privileged. The Russians had embraced all things French in the 18th century. The political emigres after the French Revolution were welcomed into Russian society and vice versa when Russians traveled to France. Both women embarked on travel in their own countries and across Europe in horse and carriage. They traveled thousands of miles, yet they wrote about these difficult trips as if it was nothing extraordinary. Their descriptions of what they saw and did, bring their lives into focus for those who read their books. Katya Gifford discusses how the world was changing, artistically, socially, and intellectually: Scientific discoveries in the 18th century were increasing human understanding of the natural world. Human intellect and reason began to eclipse faith as the guiding force of civilization. Changes in art were subtle but significant. Artists painted for the same type of clientele as those before them but the images their clients wanted, changed. Art became more secular, more refined, more delicate, more sensuous, more intellectual and more emotional. These changes suited Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun to perfection. She not only encouraged the changes but also introduced more modern features to portraiture. Nobility and the aristocracy maintained their claim to rule by inherited right, but their power was challenged, and their authority was eroded by an increasingly educated population (examples: The American Revolution, 1776 and the French Revolution against King Louis XVI, 1789). The 17th century had examined physical reality, the 18th century examined the mind—reveries, ideas, ideals and emotions. Countess Golovine: Our subject was born in 1766 and lived her first 14 years in Petrovskoie, (now Petrovskoya) in the country. Their residence was in the province of Moscow, 352 miles (566 km) north-east of that city. Her father was Lieutenant-General Prince Nicholas Fiodorovitch Galitzine (1720-1780), and her mother was Prascovia Ivanova Chouvalov (1734-1804). Both parents were from ruling class families although little is written about her father. Her mother was the sister of Ivan Ivanovitch Chouvalov, (1727-1797) who was a favorite of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, the daughter of Peter the Great. Count Chouvalov was responsible for the establishment of The Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg and the University of Moscow. He had spent some 15 years in Europe collecting hundreds of artifacts following the death of his illustrious friend, Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. Barbara and her family spent her early years involved with their local, rural neighbors who were not thought to be particularly remarkable. Her mother devoted herself to Barbara’s education but was not able to provide her with what were considered “proper advantages” because they were too far away from their more powerful relations. She did, however, instill the important values of the time for young, female members of the nobility; one must care for others and always provide a hospitable home, intelligent conversation along with literary and artistic abilities. She was taught to understand the importance of virtue and learned values that she held to all her life, no matter the consequences. There would be no infringement of her principles or of the independence of her judgement! Suddenly in 1780 her whole life changed. Her father passed away, her younger brother (Ivan) had died in 1777 and Princess Galitzine, (Barbara’s mother) decided to join her dearly beloved brother, who had now returned from Europe and was living in St. Petersburg. He in turn, was a bachelor and with no other relatives, concentrated his love on his sister and her daughter. Ivan Ivanovitch Chouvalov lived in a house on the Nevski Prospect, at the angle of great Sadovaia Street. It was a major thoroughfare in the city and also in the historic city center. Demidov Mansion, build in the 1800’s at the corner of the two streets gives an idea of the elegant architecture in the area and the type of carriages, whose drivers waited for their owners patiently, no matter what the weather was.

Barbara and her mother lived next to Count Chouvalov but a door between the two made a happy family home for all of them. The treasures that her Uncle had brought back from Europe soon helped fill in the gaps in Barbara’s education. She discovered aptitudes for art, music and literature. She was known for some of her artworks in her time. She also sang and even composed and gave successful concerts at Tsarskoie-Sielo, the former Russian residence of the Imperial family and visiting nobility. (Catharine Palace and Park) It is 15 miles south of St. Petersburg. She also performed at The Winter Palace, the official residence of the Russian Emperors from 1732-1917. Barbara would soon be involved with the very upper echelons of society.

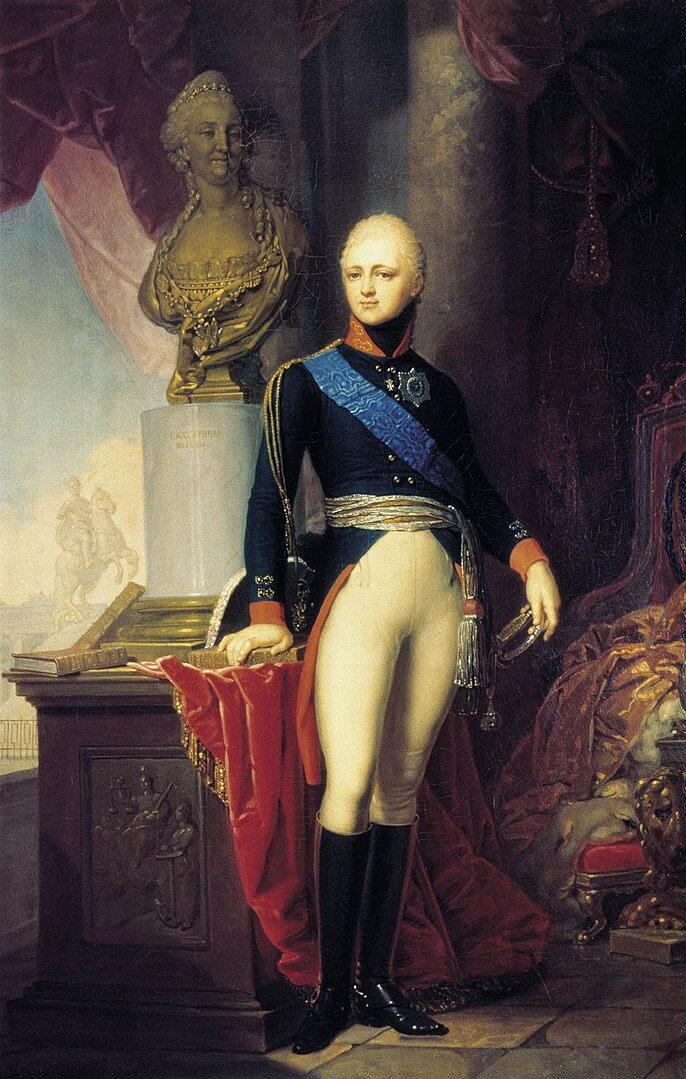

She was 14 years old when she arrived in St. Petersburg and by the age of sixteen, she had been appointed as a maid of honor in the court of Catherine the Great. There were only 12 unmarried, young women in this position, and they came from the highest nobility. Each served The Empress and it was here that Barbara found her greatest friendship with the young Grand Duchess Elizabeth who would become Empress Elizabeth, wife of Emperor Alexander I (grandson of Catherine). It would prove to be a friendship that much defined her and was in fact her eventual downfall in the Court. It was not of her own making and came about because of malicious gossip on two sides.

Although it is said she was not a great beauty she had definitely been noticed. Her many charms and talents made her a favorite of members of the court, but she refused to become embroiled in the intrigues, both political and sexual that swirled around the nobility. She was known as “the little dragon of virtue.” A week in the Court as described by Barbara: (from, Memoirs of Countess Golovine) “I went to Court every day. On Sunday, there was a large gathering at the Hermitage; the diplomatic corps was admitted, and the first two classes, both men and women. The Empress (Catherine the Great) held a formal reception of her guests in the drawing room. Afterwards they followed her to the theatre. There was no supper. On Monday there was a ball and a supper at the Grand Duke Paul’s. (Paul I, son of Catherine) On Tuesday, I was in attendance. My companion and I spent part of the evening in the Diamond Room. (Literally contains the treasures that belonged to the Court including the crown, the sceptre and the orb). The Empress played a game with her old servants. The two maids of honour were seated near one table; the men in attendance kept them company. On Thursday, there was a small gathering at the Hermitage with a ball, theatrical performance and supper……The Grand Duke and Duchess entertained on Saturday, the ball began after supper and ended very late. We went home by torchlight, which produced a novel and pleasing effect on the ice of the beautiful Neva (the river). This time was one of the most brilliant in the history of the Court and the capital; everything was harmonious.” She met her future husband for the first time in 1782 at court and fell madly in love with him. However, her mother felt she was too young to marry and that Count Golovine needed more years to mature, that is, sow his wild oats, which he did. He went off to Paris for 4 years and managed to produce an illegitimate son and later a daughter. However, these were usual affairs, and Countess Golovine paid for the education of his daughter who later married the traveling companion of Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, M. Auguste Louis Riviere. She also took charge of the son. Count Golovine was also of the noble class and was thought to be one of the wealthiest in the country. They did marry upon his return from France. The ceremony took place in the Winter Palace, Oct 4, 1786. Countess Golovine remarks in her memoirs, “Her Imperial Majesty fastened my diamonds on my head. The Empress saw my delight, and gently raising my chin, her Majesty did me the honour of saying: Look at me; really, you are rather pretty.” Their marriage was a love match. She was 19 and he was 29. They had two daughters but lost two other children. Count Golovine managed to lose most of his family wealth over the years. Although he frittered away his family fortune, he was always considered an honest and forthright man and managed to remain a valued person in the Court. Their home in St. Petersburg was “a place of discreet but singularly attractive hospitality in which, in St. Petersburg as in Paris, two select societies almost merged together by the stream of emigration which was established between the two countries. The mistress of the house, witty, sensitive and excitable, is possessed of great talents and a love of fine arts.” Their home was always full of people, staying or living with them. The Countess kept her mother with her until she died. Her interesting, rather turbulent life was complicated when Catherine asked her to care for the very young Princess Louise of Baden when she arrived in Russia, November, 1792. The Countess had been in the service of the Empress Catherine for ten years when she made arrangements for Princess Louise of Baden, (later known as Elizabeth Alexeievna, Empress of Russia, during her marriage to Emperor Alexander I) to come to Russia with the prospect of a betrothal to her grandson, Alexander, who was the son of The Grand Duke Paul and his wife, Grand Duchess, Maria Feodorovna.

The Princess Louise of Baden was 12. Alexander was 14. Catherine had chosen Countess Golovine as a companion to her precisely because of her “little dragon of virtue” reputation and the extreme youth of the bride to be! Countess Golovine was 11 years older than Alexander and 13 years older than Elizabeth and she was to protect this very young girl from at least some of the pitfalls of court life. The two became close friends, sharing confidences, activities in and out of court and eventually would pledge “undying love” for each other. This type of relationship was fairly common between females at the time. Countess Golovine took it all very seriously, and her emotional tie to this young woman, who would become The Grand Duchess Elizabeth and then Empress Elizabeth, was to last her whole life, despite the fact that she was treated very badly by both Elizabeth and Alexander and some members of the Court. She had a tendency to make the best of every situation and she tried to see the good in all, as she had been taught at her mother’s knee, but she was hurt and pained by the betrayals

Alexander and Elizabeth married when he was 16 and she 14. They had nearly a decade of growing up, sharing and enjoying a very privileged, cultured, life with the Countess and the Court but their benevolent and loved Empress Catherine had a stroke and died November 17, 1796. It was unexpected and a tragedy for the country and the Court. Catherine had made many reforms and intended that her grandson would succeed her. Unfortunately, her son Paul I became Emperor. He was enormously unpopular and attempted to reverse the reforms made by his mother. Those who influenced the court in Catherine’s time became less popular. Paul’s wife, Maria Feodorovna had become jealous of Grand Duchess Elizabeth Alexeievna because she was a favorite of Catherine’s. Countess Golovine by association, had fallen into the same category. Maria Feodorovna, as Empress became more powerful in the Court as did those who surrounded her. Rumors of intrigues attributed to Countess Golovine began to spread.

Countess Golovine at the time had been aware of an attraction between Countess Tolstoy and a British envoy. She had been advising her against pursuing this relationship and Countess Tolstoy had been staying with the Golovines as this little affair played out. Count Tolstoy, also a courtier and also jealous of both Count and Countess Golovines’ positions in the Court, had the ear of Paul and Alexander. He too, spread rumors that the Countess Golovine was indeed helping his wife in her infatuation with Lord Charles Whitworth. Fortunately, Whitworth was recalled and later, Countess Tolstoy heard of his marriage. Her passion cooled, she confessed to Countess Golovine that it took the marriage for her to see through his actions, but the damage was done to Countess Golovine. She had maintained her principles but had not been in a position to defend herself. “I no longer saw anything of the Grand Duchess Elizabeth. My devoted affection for her was still the same, but The Grand Duke took advantage of his mother’s dislike to me to deprive me of all means of seeing the Grand Duchess and associating with her.” (p. 136, Memoirs of Countess Golovine) She was hurt that they would believe such things about her. Her husband resigned his place and they left the court. “The truth was to come out later. But, even then, for various and rather enigmatic reasons, the victim of this lamentable error never regained what she lost.” (Preface: Memoirs of Countess Golovine: xviii) Count Golovine did eventually re-entered the Imperial Service, and obtained for his daughter an appointment as maid of honor, and for his wife, the rank of Lady of the Order of Saint Catherine but not until 1814. Paul I was assassinated on March 24, 1801. Empress Maria had visions of becoming The Empress, however before she could do anything about it, Alexander was declared Emperor Alexander I and he and Empress Elizabeth became responsible for the ruling of Russia. They were 22 and 24. Their relationship with the Countess remained cool. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun had been in Russia since 1795. She had met the Golovines in St. Petersburg and visited at their home: “The Countess Golovine lived rather far away, in the broad street called Prospekt…..the cold was such that at first I thought my carriage windows must be open. Upon seeing me enter her drawing-room, the Countess exclaimed: “Heavens! How could you go out this evening? Do you not know it is nearly twenty degrees? This made me think of my poor coachman, and without taking off my pelisse I at once returned to my carriage and was driven home as quickly as possible.” They were clearly acquaintances and again in St. Petersburg and together in the summer of 1801; “When spending the summer at a house on Kamenny Island (summer retreats for royals and the nobility, just outside St. Petersburg on the River Neva), lent to her by Count Stroganov, Vigée Le Brun often spent the evening with Countess Golovinia, where Prince Ivan Ivanovich Baryatinsky and the Princess de Tarante were staying. We would chat or have readings until supper. In fact, my time passed in the most agreeable manner possible.” (Le Brun 1835-1837 vol 2, pp 341-42) This may have been the time when Le Brun painted Countess Golovine, before she left for Moscow. Their departure from St. Petersburg and Russia was painful, but Countess Golovine could see no reason to stay when their enemies continued to malign them in court and she could see no way forward towards a true reconciliation. They left June 8, 1802: “I drove in my mother’s berlin with my youngest daughter, aged six, and the sister of her governess, whom my mother was very fond of, and whose name was Henrietta. In the other carriage were my husband and my elder girl, the governess and the surgeon. Afterwards came our two maids and two valets.” This arduous trip took them to Estonia, Narva, Livonia, Riga, Konigsburg, and Berlin, where her daughter became very ill and they had to stay two months. They moved on to Leipzig, Thuringia, Frankfurt, Strausburg and finally Paris October 3, 1802. The city was still in the throes of the aftermath of the revolution and the coup by Napoleon in 1799. The Golovines very easily inserted themselves into the nobility of France and continued to enjoy a privileged lifestyle despite the fact that the nobility was considered, “out of date” at the time in France. They stayed with Mme. Tarente, who was a very great friend and had been aware and involved in all the troubles in Russia. The “old noblesse” still lived on with principles preserved intact—the victim of the Revolution, according to Madame Golovine. They lived the lives of tourists, enjoying new friends and seeing the sights. “I used to go out for a few hours in the morning and again late in the evening, and devoted the rest of my time to my mother and my various occupations. (She painted again during this stay in France.) In my absence, my mother had a doctor with her, who lived with us solely on her account, my children spent their recreation time with her and Mme. De Mercy, her companion, never left her. I could have enjoyed nothing, had I not felt certain that all was well with her” (from, Memoirs of Countess Golovine, p. 273). After two eventful years in Paris, they left June 26, 1804 to return to Russia with a similar entourage of people and carriages. Barbara’s mother, unfortunately died in Dresden. She wrote: ”My husband on this occasion, as on many others, was my guardian angel. He took all expenses upon himself although properly they should have been defrayed by my brother, who inherited my mother’s fortune, and who was near us at the time, at Frankfurt-on-the Main. But my husband took real pleasure in caring for my mother after her death, as he had done in her lifetime.” (Barbara’s brother, Prince Theodore Galitzine, was curator of Moscow University and he had never forgiven Barbara for her conversion to Catholicism. They were estranged.) Once back in St. Petersburg, she resumed her life, attending some Court events and having the occasional conversation with Empress Elizabeth and Emperor Alexander I, but never with the closeness of their youth and she never regained her stature in the Court. Her growing young daughters became her concern. Her life was not destined to be a long one. Several of her friends had passed away from cancer and Barbara also fell victim. She sought treatment in France several times and finally stayed in France until her death in 1821. Her husband had also passed away in that year just ahead of her. She was 55. Her Achilles heel always, was the loss of her friendship and closeness with Empress Elizabeth. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Countess Golovine mention each other in their memoirs but it is as passing, friendly acquaintances. There is no indication of a deep, long lasting friendship between the two. Rather, they write about pleasure in each other’s company and sharing time with mutual friends. “After being an assiduous guest of the Golovine’s, during her long stay at St. Petersburg, Mme. Vigée Le Brun writes thus of her who had been her hostess: She is a charming woman, intelligent and gifted, and was often herself our only entertainment, for she received very few visitors. She drew very well and composed delightful songs, which she sang to her own accompaniment on the piano. Moreover, she was on the watch for all the literary novelties in Europe, which I believe, were known at her house as soon as they were in Paris.” (Souvenirs, ii 323-324: from Memoirs of Countess Golovine, Preface, xx) Vigée Le Brun knew her well enough to capture her personality in the portrait and to present an intimate encounter that includes the two of them but also the viewer. There are three people in this painting. We as viewers, cannot help but be drawn into it. Vigée Le Brun also painted Countess Golovine’s uncle, Ivan Ivanovitch Chouvalov. Barbara is the first recorded owner of his portrait. It is now in the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. A close up of his face reveals delicate handling of facial colors and shadows, the wispy hair is touchable and the care of the gloss on the eyes is very realistic. It is suggested that the painting may have been done posthumously, following his death in 1797. If so, Mme. Vigée Le Brun managed a very realistic likeness. He was 70 when he died, just after Paul I became Emperor and just as his niece, Countess Golovine became negatively embroiled in Court intrigues. He was a sad loss for the family.

Who is Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun? This woman was born to paint. Her tombstone epitaph says, “Ici, enfin, je repose…” (Here, at last, I rest). From early childhood to the end of her life, her greatest passion was art. She left over 600 recorded portraits and 200 landscapes for posterity, and she traveled thousands of miles across Europe to fulfill her destiny. Her first five years were spent in the care of a farmer’s wife in the country southeast of Paris. She was boarded at a convent school in Paris’ faubourg Saint-Antoine area, where she followed a curriculum reserved for daughters of the middle classes: reading, writing, catechism, music and domestic and social arts. She also covered the margins and blank pages of her books with small drawings of human figures.

She was born April 16, 1755. Her father, Louis Vigée (1715-1767) was a portrait artist whose clientele came from the upper echelons of the bourgeoisie, and he exhibited regularly in the Salons of the Académie de Saint-Luc between 1751 and 1764. Her mother, Jeanne Maissin, was the daughter of a merchant-farmer from the province of Luxembourg. In 1766, aged 11, Élisabeth returned to the family home. She had access to her father’s studio where he taught her the fundamentals of drawing, introduced her to pastels, and realized that his daughter was a better artist than him. Her father was an extremely sociable man and invited artists and writers to his home in Paris and in the village of Neuilly. His daughter acquired a lifelong taste for entertaining in this way: at the end of the Bourbon monarchy, her salon would be one of the most prestigious ones in Paris. Louis Vigée died a short time after Élisabeth had returned home. She was devastated by his death. Her mother remarried some seven months later because her financial situation was precarious. Élisabeth, however, never forgave this man, Francois Le Sevre, for wearing her father’s clothes, and she found him repellent. To distract her from her grief and get some distance for her step-father, her mother decided she should study painting seriously. Her lessons were augmented by advice from Joseph Vernet and Gabriel Francoise Doyen. Her mother accompanied her to galleries and to see private collections. As a young female student, she was not granted an apprenticeship with an acknowledged master. She was only allowed access to certain things, and so she copied historical and contemporary paintings. She worked from the model, educating herself and of course, she painted her family. By the 1770’s she had gained renown in Paris and a well-heeled clientele streamed to her studio. Her mother was ever present, whenever a man came to pose to discourage sexual advances, for she had grown into an attractive young woman. She loved music and this talent also opened doors for her to the aristocracy. In 1774, Élisabeth, her mother, step-father, and brother moved to an apartment in the Hotel de Lubert. She met Jean Baptiste Pierre Le Brun (1748-1813), an art dealer, who lived at the hotel. He introduced her to his gallery art and provided her with paintings to copy. On January 1, 1776, when she was 21, they married. Her step-father had been taking all her earnings and her mother had encouraged her to marry as she thought Le Brun was wealthy and would be a good husband. They married in secret, because he was betrothed to another and had not disengaged himself as yet. Her friends, unfortunately, warned her not to marry him after the marriage had taken place. They knew he was a heavy gambler with insatiable desires for the finer things in life and a need to acquire more and more art. She was trying to avoid one bad situation and got herself into another. He did take her earnings instead of her step-father. She had never been particularly interested in the business side of her work, even though she had been supporting her family with her paintings from her teenage years. Her situation at this point did not change much, though her husband was able to introduce her to a larger society, and she continued to learn by painting from his artworks. This same year, she received her first royal commission for portraits of Louis the XVI’s brother. These paintings are now lost. In 1778, she and her husband, bought the hotel they were living in. They renovated it and provided the family with two apartments on the first floor. They had a daughter, Jeanne Julie Louise Le Brun in February of 1880. In 1789, she and her daughter escaped Paris at the time of the revolution. Eventually on her return to Paris after her exile from France, she paid off her husband’s debt and bought the hotel from him. He had divorced her for desertion after the revolution because of her close ties to the royals. He thought he might find himself in political trouble because of her relationships with the King and Queen and her sympathy for the aristocracy at the time of the Revolution. As with many couples of this era, they remained cordial towards each other and continued to support each other. It was he, in 1799, who managed to get a group of artists and influential people together to sign a petition to end her exile from France. On her return, she did take control of her finances, which were considerable as she had made a fortune while painting her way through Europe and Russia. They never remarried. In 1778, Élisabeth painted her first portrait of the French Queen Marie Antoinette. In her memoirs, “Souvenirs”, Le Brun describes many of her subjects by their physical traits and their personalities. She was an astute observer and was quickly able to understand exactly how people would like to be portrayed. She described her first meeting with the queen: “It was in 1779, (actually, 1778) that I first did the portrait of the queen, who was in all the glory of her youth and beauty at the time. Marie Antoinette was tall, with an admirable figure, fairly plump but not too much. Her arms were superb, her hands small and perfectly formed, and her feet charming. She walked better than any other woman in France, holding her head very high with a majesty that singled her out in the midst of the entire court. But that majesty in no way compromised the sweetness and benevolence of her appearance. In the end, it is very difficult to give someone who has not seen the queen an idea of so much grace and nobility combined..….At the first session, the queen’s imposing demeanor intimidated me tremendously, but her Majesty spoke to me with such kindness that her considerate graciousness immediately dissipated that impression.” (Vigée Le Brun 1835-1837, vol. 1, p 44) The queen had been seeking an artist who would paint her to her liking and finally after many failures by others, Élisabeth’s portrait pleased her. This was a conventional portrait and its composition is somewhat awkward. She is dressed in a formal court gown, with white satin panniers and a train with a fleur-de-lis pattern. Her cheeks are very rosy, her hair an enormous pouf. It is a depiction of fashion, but it also sends a message of royal power. This is quite unlike Le Brun’s paintings that she did just a bit later in her career. The chemise dress the queen wears in 1783 caused a scandal. It was far to intimate and was replaced a month later by the more formal blue dress. Le Brun much preferred the softer, more informal styles that she soon became famous for. Both the costuming and the settings below explore the two differing styles. She always encouraged her subjects to be comfortable in their clothes as well as their poses.

In the following years, Le Brun painted 30 portraits of the queen and many members of the French Aristocracy. Driven by her talent, her desire to work, and her intelligence, her reputation grew just as her clientele did. She was attractive, a good conversationalist, and knew instinctively how to make a subject at ease. She actually sang with some of her sitters. At the intervention of the queen, on May 31, 1783, she became a full member of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, much to the chagrin of those who disliked her work or objected on the grounds of her gender.

Her self portrait in 1790 was painted for the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, following the French Revolution and shortly after her arrival in Rome. In her own words, “I did my portrait for the Florence gallery. I painted myself with palette in front of a canvas on which I am drawing the queen in white chalk.” (Vigée Le Brun: 1835-1837, vol. 2 p.38) The painting was exceptionally well received and her use of scarves and ribbons as well as the scumbled backgrounds were some of her trademarks in her paintings. She had a glamorous yet natural style and is now considered to be part of the Rococo Movement but with Neoclassical overtones.

She too, like Countess Golovine, suffered the woes of a fierce defamation campaign. Rather than the Court, it was the press in 1786. The critics did not believe that a woman could paint such paintings or that she should show her work in the salon as she had done in 1783; it was unacceptable in proper society—to show your teeth in a smile, something that was unheard of in social and art circles; and of course, there were rumors that she was having an affair. It has been said that “her move into the public domain was so radical for a woman”. A woman’s role was domestic, and she should have been concerned only with “bearing, nurturing and nourishing off-spring.” She, like Countess Golovine, was not to be deterred and despite all opposition, is considered the most radical painter of the period.

Besides the gossip and press attacks, there was the growing unrest of the populace that led to the Revolution in 1789. Anyone in the Royal family or in the Aristocracy was in mortal danger. Le Brun was the first artist to choose exile. She knew well that horrors were going to come in Paris. Some of her friends had already been murdered. [The fearful year, 1789 was well advance, and all decent people were already seized with terror…..friends had been walking at Longchamps that morning and the populace at the Etoile gate had cursed at those who passed in carriages in a dreadful manner. Some of the wretches had clambered on the carriage steps, shouting, “Next year you will be behind your carriages and we shall be inside!” and a thousand other insults.] (from Souvenirs). Élisabeth found herself living in a state of continual anxiety and sadness and finally, made up her mind to leave France. She had her carriage made ready. An attack in her home and a subsequent visit from two neighbors who were part of the rebellion but still friends helped to change her mind. They advised her to leave quickly but not in her own carriage. The streets would not be safe. She booked tickets on the stage-coach but had to wait another few weeks. On the 5th of October she, her daughter and nanny were “dragged to the stage-coach at midnight in a dreadful state of mind…..my brother and husband escorted me as far as the Barriere du Trone”. The King and Queen had been taken from the Palace of Versailles and all was chaos in Paris. She had no fears for herself once they had crossed into Italy but feared greatly for her family that she had left behind. Amazingly, she found great distraction in the Savoy mountains that she had never seen before and thinking that she would only be gone from Paris for six months or so, she took pleasure from the new scenery and sights that surrounded her. She had no idea at the time that she would not see Paris for another twelve years. Her early exile years in Italy were spent living in some of the major cities, (Florence, Milan, Naples, Rome, Venice, and Verona) where she painted her way through the aristocracy, traveled back and forth between cities, to wherever her commissions took her. She continued to learn and experiment with her portraiture skills and her reputation continued to grow as she exhibited in many salons and galleries. She collected memberships in many of the Academies in several of these cities. She was a charming person and made and kept friendships along the way. She stayed in aristocratic homes and was entertained and in return, entertained those in “high society”. In 1792 her name was added to the list of emigres, and she lost her rights as a French citizen. In 1793, she was in Vienna where she was patronized by the Austrian, Russian and Polish nobility. It was in this year that her husband published a defense of his wife’s conduct. He was imprisoned because of it and shortly after, her brother was arrested too. Neither suffered the consequences that many of her friends did as they died on the scaffold or by guillotine. The following year, Le Brun divorced his wife on the grounds of dissertion, to protect himself. In 1795, the Russian Ambassador and some of his compatriots urged her to go to St. Petersburg. They said the Empress would be pleased to meet her. She wanted to make a fortune before she returned to Paris and Russia was an opportunity. She left Vienna April 19. Her brother-in-law, Auguste Rivière, had joined her in Turin in 1792 and he continued to travel with her. He was an artist and sometime diplomat, who copied many of her portraits on a small scale. In all, he accompanied her for nine years and it was he who found his wife in Russia, the illegitimate daughter of Countess Golovine’s husband. Vigée Le Brun would spend the next six years in Russia. She arrived July 25, 1795. Again, she was embraced by the nobility. Her list of portraits done in Russia count 45 but a further 22 have been added from catalogues, letters and memoirs. More have been untraceable as they were taken away by Russian emigrants and later sold usually losing their original names. In fact, Vigée Le Brun did not include the portrait under discussion in her list. Most of the Russian portraits display an attractive simplicity, a feeling of ease, an unpretentiousness that Vigée Le Brun had helped to create while she was in Paris. Her love of theater is also visible in many of these portraits as she employs costuming to create the persona and the mood in her portraits.

She took some serious risks with portraits while she was in Russia. Before Empress Catherine died, she had asked Vigée Le Brun to paint her two nieces. The original painting showed the two young girls with bare arms and Catherine was not well pleased. It was thought that Élisabeth took the painting and added sleeves to the young girl’s gowns, however with recent examination, it is apparent that she actually painted a new canvas which is now in the Hermitage Museum. It is a slightly syrupy pose but satisfied the Empress.

Vigée Le Brun also continued to make use of her muslin fabric scarves and wound them around head and neck for pleasing effects. She did this for the young Grand Duchess Elizabeth before a ball one evening and, again, Catherine was not pleased with the look. She objected to the under-chin section. It did however, become a very popular fashion and Vigée Le Brun painted the Grand Duchess in 1797 with the scarves after Catherine’s death.

When Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun heard that her mother had died, she felt it was time for her to return to Paris. Her ex-husband had made a successful bid to have her name removed from the emigres list, and she left what had become a second home to her with deep regret. She arrived back in Paris in 1802. Her daughter had married against her wishes to a Russian that she could not approve. They did reunite but only briefly when her daughter became ill a few years later and subsequently died. She continued to paint and travel and lived until 1842. She never quite achieved the acclaim at home that she had enjoyed abroad. She was well known and respected, but the French did not have a retrospective of her work on a major scale until recently. Fun Facts: Princess Dolgoruki (Dogoruky, seen above) suggested in 1835 to Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun that she should write her memoirs. Élisabeth spoke of the Princess’s generosity after she had painted her portrait, shortly after her arrival in Russia in 1795: “the portrait done, she sent me a very handsome carriage, and put on my arm a bracelet made of a tress of her hair with a diamond inscription reading…Adorn her who adorns her century….I was deeply touched by the graciousness and delicacy of such a gift.” Their association and friendship were long-lasting and indicative of many of her relationships that she formed in Russia that continued after her return to France. Countess Golovine was also asked to write her memoirs. It was the Empress Elizabeth who approached her and asked if she would spend her leisure time writing her ‘Recollections”. The Empress offered to assist with advice but also to revise and check her writings. The assistance and the information the Empress provided gradually slowed as their meetings diminished and the latter part of the book is interesting as a biography of Countess Golovine as opposed to the Russian Court. Without the prodding that both women received, the record that is available to us now, would never have been written. Looking at the examples of her work above and then looking again at our Countess Golovine, it is striking how very modern Countess Golovine appears. There is nothing static about the portrait and as it has been described, it is Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s most radical painting of her time in Russia, in fact, perhaps her most radical painting of all. Even more interesting is that in 2010, a public poll launched at the University of Birmingham-based gallery revealed that this portrait was the most popular work of art in the Barber Institute’s galleries! It was a close contest but she won, including University staff preferences as well as members of the general public. Most comments reflected the enduring appeal of this particular piece. “It is like an old friend.” “I feel like I know her.” “The painting is full of life and feeling!” What greater tribute could be given to both subject and artist. Two hundred and twenty years later, Countess Barbara Nicolaieva Galitzine Golovine, continues to make new friends and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun continues to be informative and relevant. In January, 2019, her painting of Muhammad Dervish Khan sold through Sotheby’s for $7.2 million. This was a record amount for a female artist from the pre-modern era.

Written by Carol Morse

References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us