|

Where? Room 621 of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

When? 1595 Commissioned by? Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, the patron of Caravaggio. What do you see? Four boys dressed in semi-classical costumes. Three of the boys are playing music. The central figure is holding a lute and is thought to be Mario Minniti, a friend of Caravaggio. His eyes are moist and full of tears. The second boy from the right is a self-portrait of Caravaggio, who is playing a cornetto (a horn-like wind instrument of about two feet long; you can see the end of the instrument on the top right of the painting). The boy on the right is studying the musical score. The boy on the left is representing Cupid and is reaching for some grapes. In the foreground are two open books with musical scores as well as an unused violin. These elements seem to invite the viewer to participate with the musicians. Backstory: This painting is also known as the Concert of Youths. The boys are practicing madrigals, which are a secular (as opposed to religious) vocal music composition from the Renaissance. The song they are practicing deals with the sorrows of love. Symbolism: The boy on the left represents Cupid. The gathering of grapes by Cupid represents love. The grapes are also representing the fact that music should make the spirits light. Cupid has wings and arrows. The arrows are the main symbol of Cupid (together with the bow). Cupid typically has two kinds of arrows. Arrows with a sharp golden tip, which can fill someone with uncontrollable desire, and arrows with a blunt tip of lead, which can fill someone with aversion and the desire to flee. Cupid seems to have the latter type of arrows here. Why musicians? Musical scenes became popular during Caravaggio’s time, mainly due to the Church that started supporting various forms of music. Hence, the inspiration for this theme came from Cardinal Del Monte, who was heavily involved with the Church. Del Monte also organized various concerts at his palace. However, interestingly, the music that is played in this painting is nonreligious. Who is Francesco Maria del Monte? At age 24, Caravaggio entered the household of the Italian cardinal, diplomat, and art connoisseur, Francesco Maria del Monte (1549-1627). The cardinal paid Caravaggio for his work. Del Monte was an important art collector during his time in Rome and left a collection of about 600 paintings at his death. He commissioned more paintings from Caravaggio, including Bacchus (in the Uffizi Museum) and The Fortune Teller (in the Louvre). In addition to his love for paintings, Del Monte was also a big fan of music which explains the musical theme in this painting. In his large house, the Palazzo Madama, the cardinal hosted both artists like Caravaggio and various musicians. He paid for their musical education and gave them a place to stay.

Who is Caravaggio? Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610) was trained by Simone Peterzano, who was in turn trained by Titian. He used a realistic painting style, paying both attention to the physical and emotional state of the subjects he painted. He combined this with a brilliant contrast between light and shadow in his paintings.

Caravaggio lived a tumultuous life and was accused of murder, assault, many fights, and has served in prison. However, his sheer brilliance as an artist has given him a place in the history books. His painting style has had a big influence on the development of Baroque painting (which includes drama and an intense contrast between light and dark). Some well-known paintings by Caravaggio are his Medusa in the Uffizi Museum and Sleeping Cupid in the Palazzo Pitti.

Fun fact: This painting has been missing for centuries. While many artists in the 17th century mentioned this masterpiece, it only turned up in 1952, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced that the painting had been found and they included it in their museum. Less than two decades before, the painting had been sold for 100 pounds in England, where both the buyer and seller did not recognize that this was the missing painting of Caravaggio (mainly due to the bad state in which the painting was).

Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas.

0 Comments

The wife of Socrates The wife of Socrates

Where? Room 621 of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

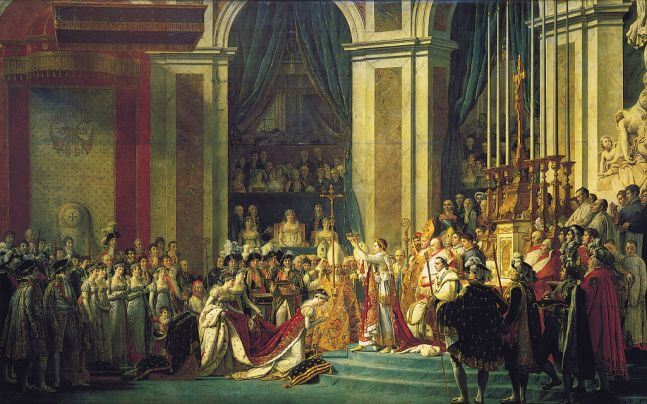

When? 1787 Commissioned by? The Trudaine de Montigny brothers What do you see? Socrates is sitting on his deathbed in his cell and is reaching for the glass of hemlock to take his own life. He is convicted to death by a jury in Athens for not believing in the Greek gods and for sharing this view with the young people in Athens. You can see the opened shackles laying on the floor. His disciples are gathered around him and cannot believe what is going to happen. The executioner from the state is holding the glass for Socrates while looking away and covering his eyes. Even in the moment just before his death, the illuminated Socrates is teaching to the people around him with his hand up in the air. Plato is sitting at the end of the bed with his back towards Socrates and his eyes closed. He seems in his thoughts, but his ear is prominently depicted to indicate that he is listening to Socrates. Plato has documented several dialogues of Socrates as Socrates himself did not leave any written documents. You can see the scroll and the pot with ink at Plato’s feet to indicate that he will document the final speech of Socrates. Sitting to the right of Socrates is Crito, a good friend of Socrates, who has his arm on his leg. Crito is sitting on a bench with an inscription of the symbol of the Athenian state. The wife of Socrates, Xanthippe, is in the left background in a red robe. She waves at us while walking away. Backstory: This painting is largely based on a dialogue of Plato, entitled Phaedo, in which he describes the death of Socrates. In this dialogue, Socrates discusses the life after death on the day before his execution. Socrates discusses various arguments on why the soul is immortal and that there is an afterlife for the soul. For his crimes, Socrates could choose between drinking the glass of the poisonous hemlock or being exiled. Given his ideas that his soul would go to an afterlife and staying true to his beliefs, he chose to drink the glass of hemlock. This painting can be interpreted in a political context. The Trudaine de Montigny brothers (who commissioned this work) were leaders of a movement that called for more open public discussion of political matters and a free market system. The motive behind this painting was to depict Socrates as an example of someone who was willing to die for his ideals. In 1787 reforms to the French political system were abandoned and there were many political prisoners. What is discussed in Phaedo? Phaedo is the fourth and final dialogue of Plato about the death of Socrates. In Phaedo, the story of Socrates is told about why he thinks that the soul is immortal and that there is life for the soul after a person dies. Phaedo also describes the death of Socrates. In short, the four arguments of Socrates are:

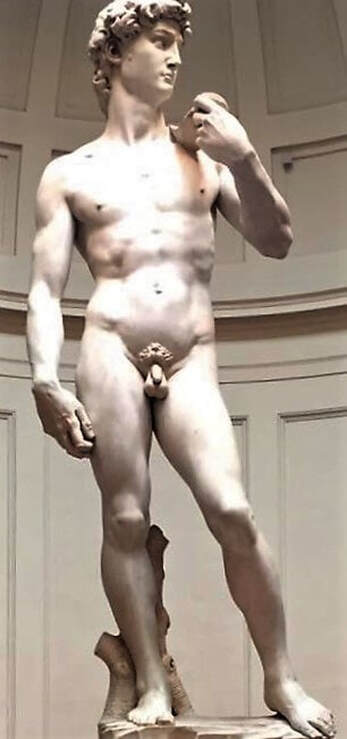

Who is Socrates? Socrates is one of the founders of Western philosophy. He was married to Xanthippe and got three sons. Socrates did not write any of his ideas on paper, but some contemporaries, such as Plato, have documented the ideas of Socrates such that his ideas have been saved for future generations. One of his most important contributions to the world is the so-called Socratic method. To solve a problem, Socrates would ask you a question. Based on your answer he would ask you another question, followed by another question, etc. He forced people to critically think about their answers by engaging them in the topic. If some of those answers led to contradicting answers, a certain hypothesis about the problem could be eliminated, and a better one could be formulated. It is basically a test of logic and will help a group of people to determine their views on a certain problem. The Socratic method has led to the currently-used scientific method that academicians use in which one starts with a hypothesis which can be rejected or accepted after research. Who is Jacques-Louis David? Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) was born in Paris. He was a Neoclassical painter and together with Antonio Canova he is one of the main representatives of this art style. In his twenties and thirties, he spent quite some years in Rome where he got inspired by the Renaissance paintings and especially by the work of Raphael. David supported the French Revolution and Napoleon, and one of his famous paintings is The Coronation of Napoleon which is in the Louvre. After the fall of Napoleon, he moved to Brussels where he stayed until his death. He loved to make historical paintings while staying true to his Neoclassical style. In this painting, you can, for example, see how the body of Socrates resembles an ancient Greek sculpture. One of his most famous students is Eugene Delacroix.

Fun fact: There are several aspects of this painting that Jacques-Louis David changed compared to the historical accounts of the death of Socrates.

Where? Room 1730 of the Main Floor of Tate Britain. Several other museums like the British Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and National Gallery of Art also own this work but do not have it on permanent display.

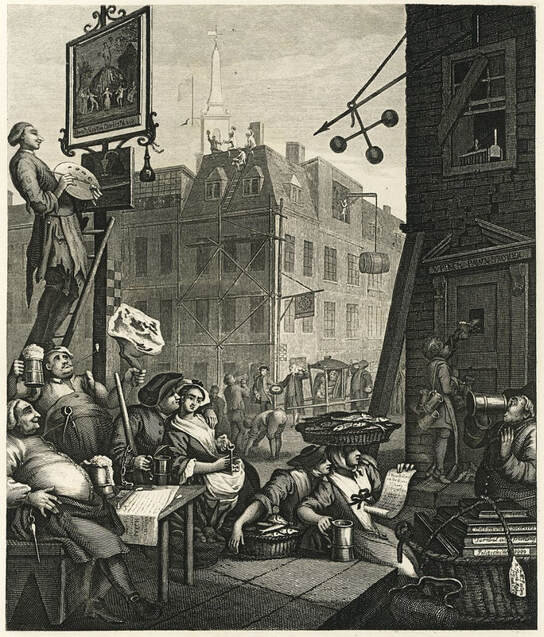

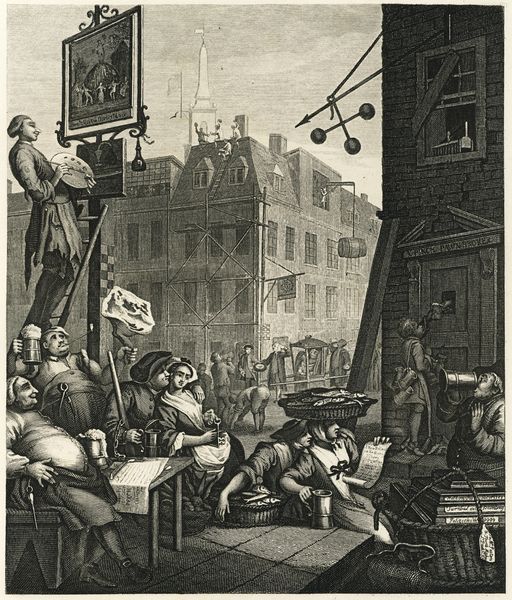

When? 1751 What do you see? Several groups of well-fed people engage in a variety of activities while drinking mugs of beer. It is the birthday of King George II, and that asks for a celebration. On the left, two corpulent men hold big mugs of beer and one of them holds a huge leg of beef in his left hand. In front of them sits a man holding a beer while sharing a romantic moment with a woman. To the right of them, a couple of women with overflowing baskets of fish pause while enjoying a beer. To their right, a young boy with mugs hanging on a rope slung over his back goes around selling mugs of beer. He stops at the pawnbroker to hand him a beer through the peek hole. The pawn shop is in some state of disrepair as people do not need to pawn off their belonging in this prosperous world where people drink beer. The other buildings are well-maintained, and the church steeple on the top is a sign that people behave morally in this world full of beer. On the bottom right, a portly man enjoys his beer next to a pile of books in a basket. On the left, a painter in ragged clothes blissfully paints a cheery picture of men and women dancing around a mountain of barley. On top of the roofs, construction workers take a break drinking to celebrate while another barrel of beer is being lifted up. Finally, in the center, a wealthy woman in a sedan chair waits as her chairmen have temporarily put her chair down to drink a beer. Laborers around them drink their beer while continuing their work in a timely manner. Backstory: Beer Street takes place during a major movement in 18th-century England: The Age of Enlightenment. This was a philosophical and intellectual movement where people began to ponder major scientific and philosophical thoughts that were captured in paintings such as The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp by Rembrandt. These ideas were published, and many people learned from them and developed them further. Another idea behind the Age of Enlightenment is that people were trying to apply these new ideas to help other people. Before the Gin Craze, French brandy was popular and fashionable, however, during the Second Hundred Years’ War between France and England, French products were considered unpatriotic and soon lost their following. This led to the Gin Craze where gin and other cheap spirits quickly became popular, and overconsumption of these drinks caused many problems among the lower-class people. William Hogarth’s print was, in essence, a piece of propaganda in favor of the British beer market. Similar to the popularity of Coca-Cola in the United States during modern times, Hogarth makes the argument that beer was not only a remedy to the unregulated gin trade but also a drink that is truly British and helps the country.

Gin Lane: At the time Hogarth created Beer Street, he also created a companion piece called Gin Lane. Most museums that own Beer Street, also have a print from Gin Lane as they were created together. Museums owning Gin Lane include Tate Britain, the British Museum and the National Gallery of Art. However, most museums do not have the prints on permanent display as they are light sensitive. The original copperplates for both works are owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

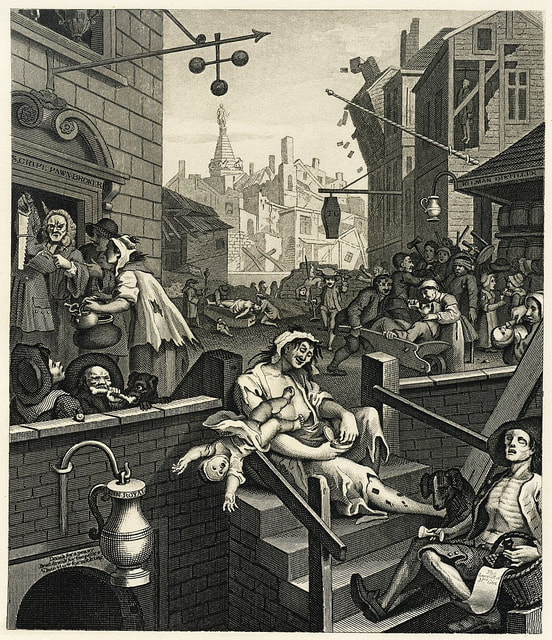

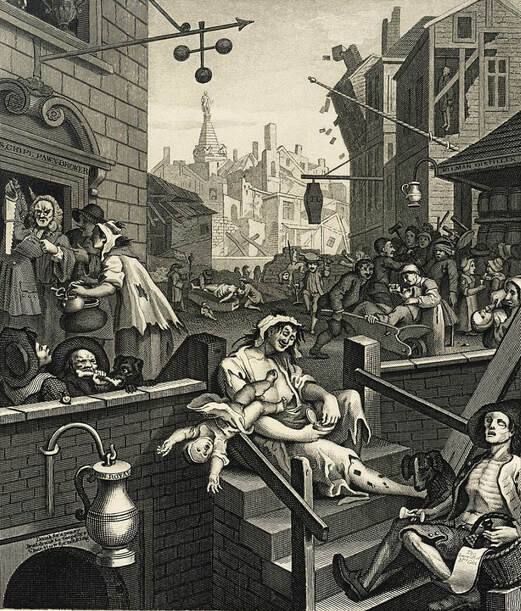

Gin Lane shows the perilous effects that excessive gin consumption can have on your life. It shows the opposite side of Beer Street where drinking gin leads to chaos, negligence, street brawls, and poverty. The only ones benefiting from the gin craze are the distillery, the pawn shop, and the undertaker.

Who is Hogarth? William Hogarth was born in 1697 in London where he would die 66 years later. Hogarth carefully examined life in 18th-century London and detailed it in etchings and painted satires. He included many symbolic features in his works such that his pieces are not only entertaining but also contain several moral messages.

Hogarth created art both for the upper and lower class. He painted works for his richer clients but also created etchings and engravings of his works that could be mass-produced and sold at a lower price to a larger audience. Among his works is a series of satirical works about the British upper class. The first painting of that series is Marriage A-la-Mode: 1, The Marriage Settlement in the National Gallery in London.

Where? Room 1730 of the Main Floor of Tate Britain. Several other museums like the British Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and National Gallery of Art also own this work but do not have it on permanent display.

When? 1751 What do you see? People in various states of physical and mental decline amid a chaotic urban setting. In the center sits a woman with ragged clothes. Her shirt is open exposing her breasts, and she has sores on her legs. She neglects her baby who falls out of her arms and does not even notice what is happening. Just down the steps from her lies a malnourished soldier who looks like a skeleton. He has his head tilted back and holds on to an empty glass of gin. A dog with a saddened expression looks over him. The soldier has a basket tucked under the crook of his arm with a bottle and note that reads “The Downfall of Gin.” To the left of the central woman, two men fight with a dog over a bone signifying how far they have fallen because of their gin addiction. Standing above them, a couple of men try to pawn off possessions to buy more gin. On the right side, more people lose themselves to the cheap spirits. People are feeding gin to each other, including children, and even a baby. In front of the distillery on the right middle, a fight breaks out and people hit each other with chairs and hammers. There is a strong contrast between the different buildings in this town. Most buildings in the background are in poor condition, except the distillery, the pawn shop, and the undertaker’s building. Backstory: Gin Lane is an etching and engraving printed on paper. Hogarth chose this technique to be able to produce multiple prints of his work that he could sell for low prices to lower-class people. Gin Lane showcases the vicious cycle of excessive drinking, pawning off your possessions to drink more, prostitution, and finally death. Gin drinking was considered a large problem in England during the time that Hogarth created this work. It was cheap and accessible to the working class, and many people got addicted to gin with all the bad consequences that result from that. Gin Craze: In the beginning of the 18th century, gin was not regulated in England, and distillers did not care much about the drink’s quality. They mixed in harmful chemicals and did anything to increase their margins. The drink became very popular among the lower class in England, and especially in London. Many people consumed large quantities of gin, which made them even poorer and led to health problems. The problems with gin led the government to take several measures between 1729 and 1751 to make gin more expensive and reduce its popularity. These measures only had a partial effect, and it was not until the 1750s that the gin consumption decreased mainly due to a series of poor grain harvests. Beer Street: At the time Hogarth created Gin Lane, he also created a companion piece called Beer Street. Prints of this work are part of multiple collections, including the British Museum and the National Gallery of Art. The original copperplates for both works are owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Beer Street presents an alternative to the ails of gin drinking. It shows the opposite of the street where we see that beer drinking leads to prosperity. It shows a town that is flourishing with healthy individuals engaging in fun activities. For example, the pawnbroker that thrived in the chaos in Gin Lane is in disrepair as no one wants to pawn items to support their habit.

Who is Hogarth? William Hogarth was born in 1697 in London where he would die 66 years later. He enjoyed creating art which explains the social ills of 18th-century England through a combination of wit and symbols that would be easy to understand for his 18th-century audience. He created art both for the upper and lower class.

Hogarth painted works for his richer clients but also created etchings and engravings of his works that could be mass-produced and sold at a lower price to a larger audience. An example of a work for the upper class is A Scene from 'The Beggar's Opera' in the National Gallery of Art. Another version of this painting is in the same room as Gin Lane in Tate Britain.

Fun Fact: In addition to being a political satirist, William Hogarth is known for his caricatures of people. Look, for example, at the man hanging from the rafters in the top right of Gin Lane or the man in the center walking down the street with a baby on a stake.

Other artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Eugene Delacroix also liked to create caricatures of people. One of Da Vinci’s many caricatures is a drawing of a Grotesque Profile. An example of a caricature by Delacroix is A Lioness and a Caricature of Ingres in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Where? Gallery 630 of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

When? 1616 Commissioned by? Unknown. Possibly a chamber of rhetoric or it was uncommissioned. What do you see? In the center, a woman dressed in a colorful and carnivalesque embroidered costume raises her right hand. She wears a wreath of laurel on her head and red beads around her neck and arms. Next to her are two comical characters. Six other characters surround the three central figures. Frans Hals painted these surrounding people very loosely. The people celebrate Shrovetide, a kind of Mardi Gras or carnival, in the days before Lent starts. To the left of the woman (from our point of view) is an older man grabbing her shoulder. He tries to say something to her. This man is called Peeckelhaering (which means pickled herring), and he can be recognized by two herrings hanging on a cord around his neck (see the two herrings next to the lower arm of the woman). Other items hanging on this cord are sausages, beans, a mussel, broken eggs, and a pig foot. In his right hand, he holds a foxtail. On the right is a man with a red cap looking at the woman in the center. He makes a sexual gesture with his hands. The table in the foreground contains various items, including a bowl with fish, an open can, half a loaf of bread, and deflated bagpipes. Backstory: This painting is also known as “Shrovetide Revellers.” Frans Hals probably depicts a play performed for Carnival. All actors in this play were men, and so the woman in the center is probably a man dressed up as a woman. She wears a wig and makeup. However, her hands are smaller than the hands of the men next to her. This feature either indicates that the man was built in a way that made it easy for him to dress up like a woman, or that she is a woman after all. Hals got inspiration for this painting from the works of Flemish artists like Rubens, Jordaens, and Jan Brueghel the Elder. He had seen their works earlier in 1616 during his 3-month visit to Antwerp. He took the modern Flemish ideas of a very busy composition and colorful figures and applied these to this painting. Hals painted the figures in the background using broad and loose brush strokes. Hals illustrates his trademark brushstrokes perfectly in the painting The Gypsy Girl in the Louvre, which he painted between 1626 and 1628. In 1907, Merrymakers at Shrovetide was bought for 89 thousand dollars by the American art collector Benjamin Altman. He left it for the Metropolitan Museum of Art after his death in 1913.

Symbolism: The two characters next to the woman in the center are two comical characters that played roles in the Baroque theater during that day. The man on the left (from our point of view) is Peeckelhaering. In his right hand, he has a foxtail, the symbol of a fool. A string with items hangs around his neck.

The man on the right is Hans Wurst. He makes an obscene gesture with his hands to the woman. Some of the items on the table are also sexual references. For example, the deflated bagpipes are another reference to the limited sexual potential of Peeckelhaering. What is Shrovetide? The Christian period of preparation for the six-week Lent. This period is strongly associated with Carnival. Shrovetide begins on the Septuagesima Sunday, the ninth Sunday before Easter. It lasts for 2.5 weeks and ends on Shrove Tuesday. The day after Shrove Tuesday is Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent. Shrove Tuesday is a day with two different faces. Some people use this day to self-reflect and figure out what sins they regret and how they can grow spiritually. Other people celebrate this day wildly, as it is the last day on which they can indulge in food and drinks.

Who is Hals? Frans Hals the Elder was a Baroque painter. He was born in Antwerp, Belgium, by the end of 1582 (or early 1583). At a young age, his family moved to Haarlem, The Netherlands, where Frans would spend the rest of his life.

During the year that Hals painted Merrymakers at Shrovetide, he also became a member of a local chamber of rhetoric called ‘De Wyngaertrancken’ (the vine tendrils). He did not participate in the performances of this chamber of rhetoric as he was a “second member,” which means that he merely admired the performances of other members. It shows his interests in depicting these plays even though his real specialty were the portraits that he painted. Among his most famous portraits are the Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman in the Cleveland Museum of Art and The Laughing Cavalier in the Wallace Collection in London.

Fun fact: Hans Wurst, the man on the right of the woman (from our point of view), was a comical character in 17th-century performances. Hans Wurst means John Sausage, and he can be recognized by the sausage dangling from his cap. He waved this sausage in front of his fellow players to make fun of them. Hans Wurst makes an obscene gesture. He puts the thumb of his left hand in between the middle and ring finger of his right hand, which form a circle. This is a gesture suggesting to penetrate the woman.

Interestingly, this gesture was not visible in the painting when the Metropolitan Museum of Art received it in 1913. Only after they cleaned the painting, the gesture became visible. During this cleaning in 1951, the six figures in the background were also discovered. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us