|

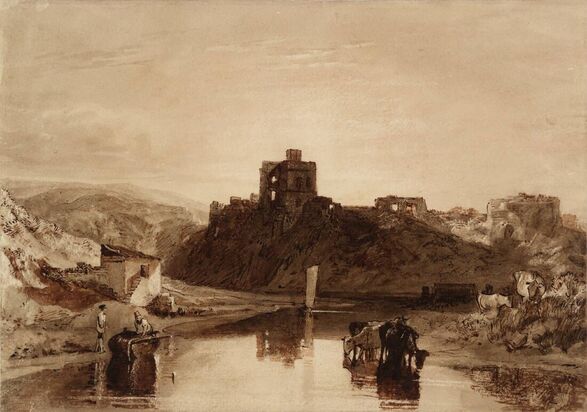

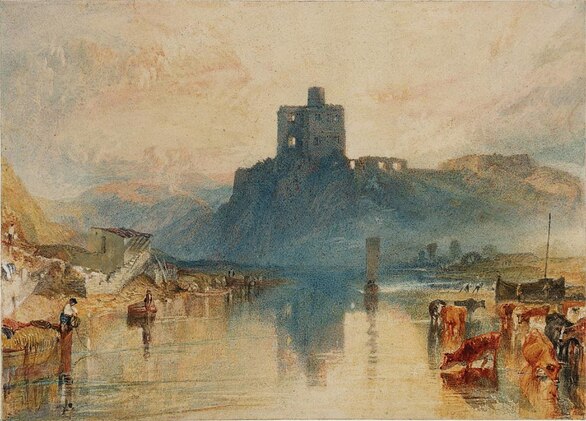

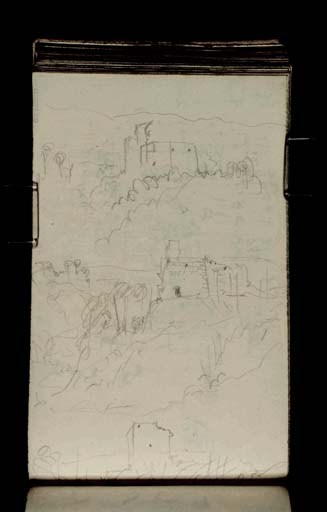

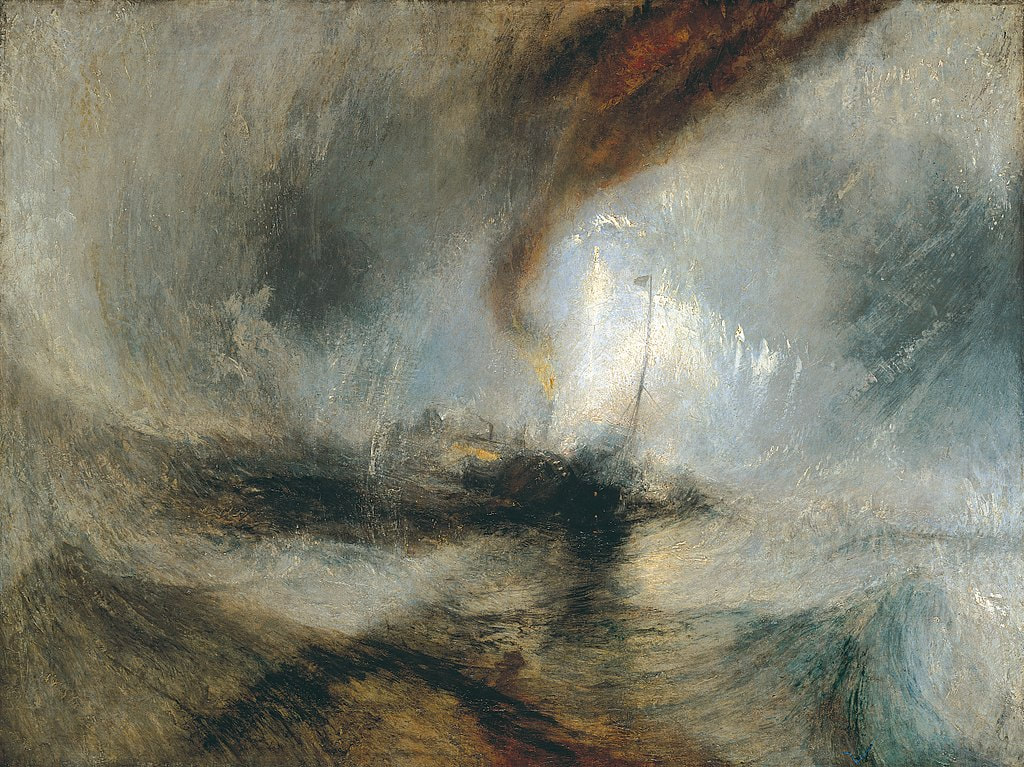

Where? Tate Britain in London When? c. 1845 Medium and size? Oil on canvas, 90.8 x 121.9 cm; classified as unfinished. What do you see? The light blue to navy ruins of Norham Castle draw our attention through the narrowing path of the river. The blinding, diffused light of the first rays of sun in the central position and its’ layered swirls of colors, are reflected in the river. The golden mist (called golden fluid by some scholars), spreads across the sky and the river, merging with the blues that predominate and define the background of the landscape. Misty hills and riverbanks are joined together by the morning light but are still recognizable as separate parts of the scene. In the foreground, cattle wander into the river from the shore, barely visible in the grasses. Two of them are suggested by a mere smudge of darker color on the right side of the painting, with one, drinking peacefully in the river. It is a bucolic scene. Backstory: This oil painting was found in Turner’s studio after his death and was accepted by the British nation as part of the Turner Bequest in 1856. We are used to seeing paintings in this genre and style but contemporaries of Turner, thought he had lost his mind. Was he suffering “senile decrepitude”? How could he possibly produce such nonsense? His most devoted supporters wondered what had happened to him. How did he arrive at this point in his art and his life? This particular painting and its predecessors allow us to look at the development of this painting and his work over time. Understanding the man is more complicated, and in many ways, he remains an enigma today despite the thousands of articles and books that have been written about him. Norham Castle: This castle sits in the northeast corner of England, directly on the border with Scotland. The countryside and coastline are mountainous, rugged and wild with one of the coldest climates in the country. The castle is on the banks of the River Tweed and for 450 years, from the twelfth to the sixteenth century, it was part of the defense system that existed between Scotland and England. The Tweed fords were an easy crossing point into England and the attacks and defense between the two countries were fierce and violent. Henry II, King John and Elizabeth I were part of its history. Elizabeth refused to put any more money into the castle’s maintenance and it fell into disrepair by the early 1600’s. North of England Tour of 1797: When Turner was 22, in 1797, he took an eight-week tour of the North of England. He was already known as an architectural draughtsman from his work following tours of the West Country, The Midlands and Wales, but this was his first glimpse of what landscape painting could become for him. He covered close to 1000 miles and filled two large drawing books with nearly 200 sketches. On his return to London, he began working some of his sketches into watercolors. Norham Castle was a particular inspiration to him and one that he returned to for the rest of his life, experimenting, developing and changing his own understanding of how to achieve the atmospheric effects on paper or canvas that were so important for him to portray. Norham Castle on the Tweed, Summer’s Morn: He exhibited his first watercolor of Norham Castle at the Royal Academy in 1798. Another went into a private collection. Poetry as description, was important at this time and the Royal Academy had just begun to allow quotations to accompany paintings in their exhibitions. Turner attached a few lines from a poem by James Thomson, The Seasons, describing sunrise and his chore was to somehow match the colors and effects in the painting with the poem……”kindling azure, fluid gold”. He experimented with his pools of colors, using “stopping out” techniques that left under-washes exposed but textures in the water, alive with morning color. He maintained the contrast of day and night in the dawn by using light and shade techniques, (chiaroscuro) seen in the mid-section below the castle. By stopping out (covering) the windows of the castle when he painted the darker parts of the building, the rising sun is seen, glinting through the ruins of the castle tower. The cottage and cattle in the foreground are realistically presented as in his topographical work. The morning mists are prominent in the valley below the castle. Color Study of c. 1798: One of the “color studies” executed by Turner as he worked on the two finished watercolors of 1798 is below. The back of this sheet was also prepared with washes of various pigments as Turner explored the ways and means of achieving the luminescence and transparency he sought. There is a light wash of color underneath the whole painting. Further layers of colored washes are visible in the sky and the water. The boat is a mere suggestion made by three shapes, “stopped out”, after the initial wash. We see the body, the sail and the reflection of the sail in the water. The anatomy of the rocky banks is drawn and painted in detail to provide the structure for the greenery that is in the finished watercolor. Each element actually compels the viewer towards the castle. Turner continued experimenting and playing with his colors. He was “the first watercolorist, starting around 1815 to exploit the mediums resources for wet in wet effects—using the wet paper to float and mingle large areas of color, then blotting and scraping to shape lights and outlines. This range of techniques with the layering of glazes…the transparent color, washed over a previous dry layer of water color paint he applied…., gave him an unparalleled ability to describe the effect of atmosphere and light. He made his scenes even more dramatic by increasing the size of his paintings to three feet or more.” (Watercolor Artists) Norham Castle for Liber Studiorum (c. 1816): Turner had begun his professional career as an engraver. He worked, supplying designs for the Copper Plate Magazine and the Pocket Magazine. The popularity of prints spread throughout the country and enabled artists to not only sell their work for good profit but to bring the countryside to life for the population. It follows that Turner would use this medium for his own work and Norham Castle appears again in 1816 as part of his Liber Studiorum. This was a collection of 71 prints in etching, an engraving method for which the design is cut or bitten into the metal plate through controlled immersion in acid and mezzotint, a relief printing process developed in the 17th century, where the whole surface of a metal plate is covered with burred dots made with a tool called a rocker. The burrs give half-tones and lights depending on the depth of the scraping or burnishing. Turner worked on and published these pieces from 1807-1819. His Norham Castle Liber design, was developed from the pencil study he had done in the Northern England Tour sketchbook and the subsequent watercolor studies that he did in 1798. The Liber design is altered. The castle is much more front and center with a powerful command of the scene from on high. The crisper, distinct lines provide better definition of each element in the etching compared to the first painting. The fishermen and cattle in the foreground are so much closer that the viewer gets the impression he might be in a boat in the middle of the river, as part of the scene. J.M.W. Turner created the etching for the print and Charles Turner, (not related) one of his collaborating engravers, worked the mezzotint. These works were an indication of where Turner wanted to take the genre of landscape and he categorized each work in the Liber Studiorum as Marine, Mountainous, Pastoral, Historical, Architectural, and Elevated or Epic Pastoral. As Turner traveled and discovered more and more of the beauty of his own country and the continent, he was able to produce and deliver these works to the public, who had never seen such landscapes before. Rivers of England of 1822-1823: In 1822-3, he produced another painting of the castle which was part of his series of watercolors; Rivers of England. The castle remains dominant but the people and the animals demand equal attention in this version. David Hill in Turner in the North suggests that there are political overtones in the painting. The castle is on that infamous border and on the left he sees the Scottish side of the river with the fishermen in plaid kilts, using row boats with a rustic cottage and rugged country behind. On the right, the English use sailboats. Two men work the boat on the far right. The cattle appear to belong to the English side. Large trees surround the village nestled in the valley beneath the castle. Just behind the cattle, there are three people working the land producing crops to feed both animals and people. These signs highlight the difference in prosperity of the two countries which was the reason for the fortification in the first place. David Hill believes there were still problems that required resolution and that Turner was painting that into the picture. Turner has fully developed his handling of washes, glazes and color effects. The morning sky is detailed and wind effects on the rising mists are apparent. Vaguely seen behind are the rough hills and valleys. The castle firm and proud, sits in the central position. The water glistens with the new dawn light as animals and people go about their daily affairs. Turner now has full control over the nature he portrays for his viewers and included are the people who belong in it. He is a storyteller and with his prodigious talent he brought nature, history, poetry and knowledge to the British public. Norham Castle Sketches of 1831: Turner traveled all his life. His great energy allowed him to cover the length and breadth of the British Isles as well as the continent with tours almost every year. He returned to the North of England in 1831 with Robert Cadell, (1788-1849) a book publisher, and they passed Norham Castle in the stagecoach. Walter Thornbury, in his book, The Life and Correspondence of J.M.W.Turner, recounts this story: Turner took off his hat and made a low bow to the ruins upon observing which Cadell said, “What the devil are you about now?” “oh” replied Turner, “I made a drawing or painting of Norham several years since, it took and from that day to this I have had as much to do as my hands could execute.” Turner made three new sketches of Norham Castle on this trip. Robert Cadell’s diary indicates that the two of them passed the castle on August 10, 1831 as they traveled from Kelso Abbey to Berwick. The sequence of the sketches from west to east follows the coach route as it went past the castle on the way to Berwick-upon-Tweed. The haste of the drawing is evident in the rapid swirls with bare details of the buildings. Turner’s memory must have been almost photographic as he created minimum details in many of his on-site drawings, but then filled in specifics later in his studio either in the drawing or in his paintings. He wrote notes about colors and annotated many drawings to help himself remember the scene. CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0, Tate Britain. The incident may have rekindled his interest in Norham Castle and perhaps led to the unfinished watercolor below. It was another step closer to the unfinished oil painting of around 1845. Norham Castle at Sunrise of c. 1830: This unfinished beginning is a clear demonstration of the layering and overlapping and actual messy process that Turner went through to find the composition and the coloring that he was looking for. One can feel and see his hasty, forceful, impatient experimenting in his brush strokes. The castle is visible and the cottage is just barely taking shape in the foreground. There is another drawing on the other side of the page with outlines that can be vaguely seen on the right side. The blending of colors is yet to come and in fact, never materialized for this particular work. This is a good thing as it is easy to see how he began blocking in his colors, setting out his composition and enabling us to see how much he changed each work of Norham Castle over time. By the 1840’s, the rigidity of Turner’s topographical training and the careful finishing touches that his contemporaries, both fellow artists and his public demanded, had for the most part, disappeared from his work. Turner was applying the same principles of his water color layering techniques with his oil paints. He thinned his oils and applied them to the canvas in the same way he applied watercolors to paper and eventually with experimentation, he achieved similar results. Light and atmosphere presented in a vortex of reality in the sky and reflection in the water, are features in so many of his finished paintings, whether they are marine scenes, mountain scenes or historical statement. Viewers are invited into the central part of the vortex to feel whatever Turner felt or saw. His theme in the 1796 oil painting was man’s vulnerability to the face of nature’s power. The fishermen are pushed perilously close to the jagged rocks of the Needles, near the Isle of Wight, by forceful waves. In 1842, he used a snowstorm to depict the same theme but his style had changed completely. The public was outraged. One person is reported as calling it, “nothing but soap suds and whitewash”. The conventional standards had been breached and there was outcry. Had he gone mad with his crazy swirls of color? Yet, Turner was trying to present the truth. He said he had been tied to the mast of a ship in order to paint the scene and he had feared he would not survive. Scholars today doubt the veracity of the tale but perhaps not the wrath of nature, or the visceral reaction that viewers experienced to the painting. Ruskin later called him “the Father of Modern Art.” Turner had no intention of showing Norham Castle, Sunrise 1845, at the time and if he knew how iconic a work it would become, he would be shocked. He was deeply criticized for these later works as familiar objects emerged from mist, or clouds or sea or steam. He continued to be involved in his professional life although there were a few who gave up on him. From the 1840’s onward, he hid his personal world from his colleagues and the general public to an even greater extent. Twenty years after his death, his paintings were studied intently by Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro and Turner’s “atmospheric creations played a major role in the development of their art” (Khan Academy, Who is JMW Turner). He was by no means an Impressionist or an abstract artist. Even as his paintings gave way to the luminosity of light, air and wind, each artwork remained whole. If you cover the cow in the water in Norham Castle, Sunrise with the tip of a finger, it is simple to see that one animal grounds the whole painting. We know how deep the water is and from that we know where the ground is in relation to the other elements of the work. The horizon is visible and the two features are all that are necessary to understand the structure of the painting. We are actually looking into the sun and the scene becomes an impression because the brilliance only allows a partial view. He painted what he saw.  Self-portrait (c. 1799) by Turner Self-portrait (c. 1799) by Turner Youth: When he was 14 years old, (1789) Turner was accepted as a student at the Royal Academy School of Art. He had a long relationship with the Academy, elected Associate Royal Academician in 1799, Royal Academician in 1802 and Professor of Perspective, from 1807 to 1837. He was not a good speaker and rarely lectured and when he did, his students found it difficult to comprehend his ideas. In fact, he had difficulty expressing himself all his life. He exhibited watercolors at the RA in 1790, age 15 and in 1796, age 21, he exhibited his first oil painting. History painting was heavily promoted by the RA at the time. Turner however, aimed to elevate the status of landscape painting. He wished to highlight the expressive power and emotional range of landscape art and to prove that it was worthy of equal attention whether the painting was in oils or watercolors. It is believed that Turner painted this to mark his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy. This membership meant that he could exhibit his works in the Academy without fear of rejection by any members of the committee. This was an important moment in his career. He was only 24 years old. Later Life: By 1829 (age 54) his travels had taken him far and wide, and he began to visit Margate. He had spent time there in his early youth and the area is where he first began drawing and found his love of nature and the sea. He stayed in a lodging house, run by a Mrs. Sophie Booth and her husband. When her husband died, Turner and Mrs. Booth began a relationship that is now assumed to have been romantic. She became a devoted companion. It appears her former husband had left her financially independent and she stated after Turner’s death, that following the first year of their relationship he had never contributed anything to their “mutual support”. He was a very wealthy man so the penury that he learned in his youth, followed him throughout his life. She has been described by various people as a large or fat woman, uneducated and crass but Turner must have felt otherwise as he wrote her poems and gave her drawings and paintings. He must have enjoyed her company as they were together for 18 years. Turner became known as Mr. Booth when he was in Margate and wore a navy great coat. The locals called him “Puggy Booth” or the “Admiral” and they were known as a couple. In 1846, they bought a house in her name, on Cheyne Walk in Chelsea. Their relationship came to an end when he died in this same house. Turner had kept this relationship from his Academy friends. When they did find out, there was much criticism: Why did he not chose a more ladylike person? She was an inappropriate woman for a great artist. Perhaps it boiled down to the fact that the Academy “required its members to be men of fair moral character as well as artists of distinction” and he felt he would “prejudice his standing as a Royal Academician”, or he preferred the company of not so genteel women, or it was just his never-ending need for mystery and secrecy, in his personal life as well as in his art. John Ruskin met Turner when he was 22 and Turner 65. Ruskin’s initial reaction to Turner may be the best description of the duality of the man and how he was viewed at opposite ends of the scale by those who knew him. Everybody had described him to me as coarse, boorish, unintellectual, vulgar. This I knew to be impossible. I found in him a somewhat eccentric, keen-mannered, matter-of-fact, English minded gentleman: good-natured evidently, bad tempered evidently, hating humbug of all sorts, shrewd, perhaps a little selfish, highly intellectual, the powers of his mind not brought out with any delight in their manifestation or intention of display, but flashing out occasionally in a work or a look. (Anthony Bailey from Ruskin, Praeterita, p. 276) He would be known as an “eccentric” or a “loner” today. He was difficult, competitive and gruff at times with his fellow artists and had uneasy relationships with most of his business associates. However, he was the opposite side of the coin with his friends. He had long-running friendships with Walter Fawkes of Farnley Hall in Yorkshire and Lord Egremont of Petworth in Sussex. He spent many happy times with both families, staying with them at their estates, paintings pictures, playing with their children and enjoying holidays with them. To them, he was a jovial, entertaining, intelligent man whose company they sought. No friend had a bad word to say about him. Today, we can know him through his paintings. A cursory glance through his work reveals some of his genius, and may find the art lover going back again and again to enjoy the scenery, the colors, the sun and the sky or the history and poetry that Turner left to his nation. Fun fact: In February of 2020, The Governor of the Bank of England unveiled the twenty-pound note with the self-portrait of Turner, against the backdrop of The Fighting Temeraire, a tribute to the artist and to the ship that played a role in Nelson’s victory at The Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. The poignancy of the painting is seen in the ghostlike sailing ship, without sails, being towed by the incoming paddle-wheel steam tug with its fire and smoke signaling the end of an era and the beginning of another. Turner was there with his observant eye, to portray not only the story but also the emotion of the moment. Written by Carol Morse References

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

Museums

- Alte Pinakothek

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Bargello

- Barnes Foundation

- British Museum

- Church of Sant’Anastasia

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Frans Hals Museum

- Galleria Borghese

- Gallerie dell'Accademia

- Getty Museum

- Guggenheim

- Hermitage Museum

- Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Legion of Honor Museum

- Louvre

- Mauritshuis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Musee d’Orsay

- Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery in London

- National Gallery of Art

- National Museum in Poznań

- Norton Simon Museum

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

- Palace of Versailles

- Palazzo Pitti

- Palazzo Vecchio

- Petit Palais

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Prado

- Pushkin Museum

- Ravenna Art Museum

- Rijksmuseum

- San Diego Museum of Art

- Santa Maria delle Grazie

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Städel Museum

- Statens Museum for Kunst

- Tate Britain

- Tate Modern

- Timken Museum of Art

- Uffizi

- Vatican Museums

- Wallace Collection

-

Artists

- Altdorfer

- Anguissola

- Berlin Painter

- Bosch

- Botticelli

- Boucher

- Bronzino

- Bruegel the Elder

- Brunelleschi

- Cabanel

- Caillebotte

- Canova

- Caravaggio

- Carpeaux

- Cezanne

- Cimabue

- David

- Degas

- Delacroix

- De Maria

- Donatello

- El Greco

- Fontana

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard

- Gauguin

- Gentileschi

- Gericault

- Gonzalez-Torres

- Goya

- Hals

- Hogarth

- Hokusai

- Ingres

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lippi, Filippo

- Longhi, Barbara

- Lorrain

- Makovsky

- Manet

- Massys

- Matisse

- Merian

- Michelangelo

- Mochi

- Modigliani

- Monet

- Panini

- Parmigianino

- Perugino

- Picasso

- Pisanello

- Raphael

- Rembrandt

- Renoir

- Reynolds

- Rivera

- Rodin

- Rubens

- Scultori

- Seurat

- Steen

- Tintoretto

- Titian

- Toulouse-Lautrec

- Turner

- Uccello

- Van der Weyden

- Van Dyck

- Van Eyck

- Van Gogh

- Van Hemessen

- Vasari

- Velazquez

- Vermeer

- Veronese

- Vigée Le Brun

-

Locations

- Books

- About Us